When Hanno the Great marched against the Roman Republic with an army of 20,000 outsourced Numidian troops in 241 B.C., he led himself into possibly the world’s first contracting failure. After being defeated by the superior Roman navy, his refusal to pay the mercenaries led to a three-year battle that almost cost him his crown and his life.

Since then, government outsourcing has come a long way. While much of the world is experiencing slow growth and recession, the transfer of responsibility for the delivery of services to nongovernmental entities has become a growth sector. Between 2000 and 2009, government outsourcing grew 3.3 percent annually within the countries of the OECD, outstripping these nations’ annual GDP growth of 1.5 percent. In the U.S., federal government spending on contractors alone reached $320 billion in 2010, an increase of more than 25 percent in just three years.

Yet despite this spending, outsourcing continues to face considerable challenges, particularly when it comes to large and complex long-term agreements. The challenges stem primarily from the conflicting interests of government, which aims to get the most for its money, and providers, which typically are looking to maximize profit.

One approach to mitigating this conflict is “smart outsourcing,” which goes beyond a contract’s fine print to focus instead on relationships, retention of know-how, and flexibility. Getting these elements right can be as critical to success as the written contract itself.

Outsourcing Growth Brings Challenges

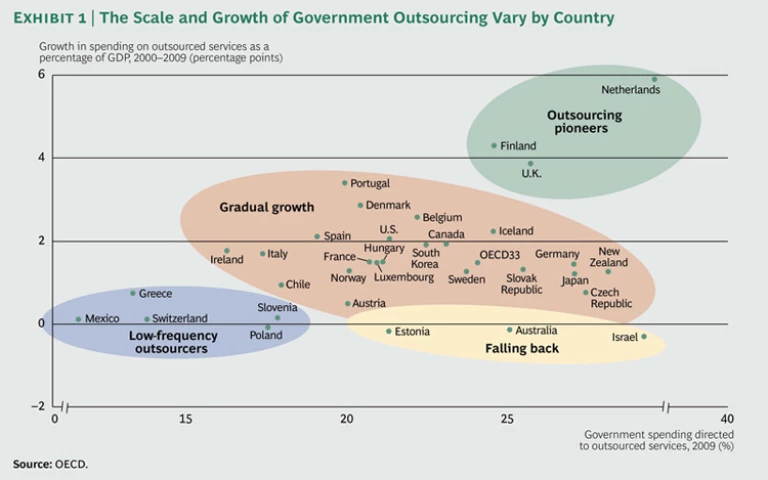

Outsourcing expanded dramatically in scope and scale between 2000 and 2009, with the U.K., Finland, and the Netherlands leading the way. On average across the OECD, nearly a quarter of government spending is on outsourcing, but there is a great deal of variation, from around 12 percent in Mexico to as much as 38 percent in the Netherlands. (See Exhibit 1.) Under these outsourcing deals, the government remains the ultimate financer of the service, with a legal contract outlining the details of the arrangement.

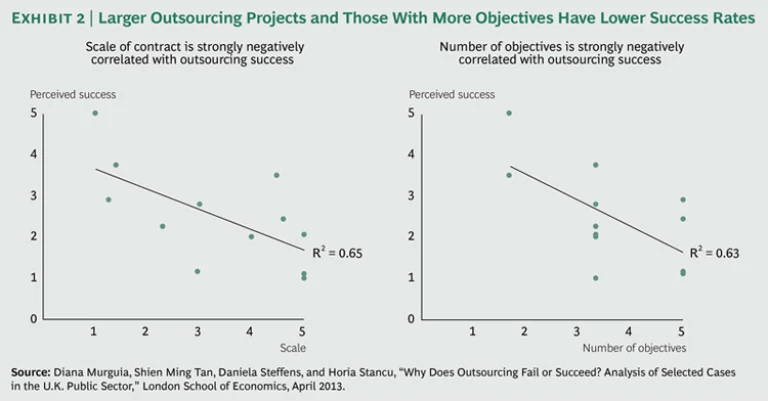

As the scale of outsourcing has expanded, its complexity has increased. Outsourcing has moved beyond transactional services, such as waste collection and property management, to include services such as care for the elderly and the disabled. But with increasingly complex outsourcing arrangements have come missteps. A case in point was the flurry of lawsuits over the state of Indiana’s $1.6 billion contract to outsource the management of its welfare and Medicaid payments. Such disputes are hardly surprising. Recent research conducted by graduate students at the London School of Economics found that larger projects are less likely to succeed than smaller ones and that those with multiple objectives have lower success rates than more focused deals. (See Exhibit 2.)

Barriers to Success

One of the reasons that outsourcing arrangements go wrong is that governments rely too heavily on contracts to manage complexity. Often their aim is to write the perfect contract—one that anticipates all possible eventualities—so that the legal system can be used to hold providers accountable for failure. The result is that providers are interested only in meeting the contract’s requirements, rather than responding effectively to unforeseen problems, changing focus when priorities shift, or investing in innovation.

The downside can be significant. In 2003, London Underground, the government body responsible for public transportation in the city, struck a 2 million-word contract with two consortia to maintain, renew, and upgrade Victorian-era tube lines. The contract was so detailed that it defined, among other things, the minimum size of litter that contractors were required to collect. In the end, the contract did not insulate the government from the financial problems experienced by its providers, and by 2010, the work of maintaining and upgrading the underground was back in government hands.

Of course, any outsourcing deal does require a solid written agreement to detail terms on pricing, performance, grounds for termination, and policies for altering the deal. But governments that focus solely on contracts to define their outsourcing arrangements are missing an opportunity.

A Business Relationship Beyond the Contract

Smart outsourcing is a set of tried-and-tested techniques that drive the development of a more intense, collaborative relationship between governments and providers. And while these techniques, used in both private- and public-sector organizations, add costs—including additional human-resource expenses—they increase the odds of success. The investment makes sense for contracts that meet some of the following criteria:

- The service is critical.

- The quality of the service is difficult to measure and monitor.

- There is uncertainty about what the government needs and what the costs will be for the provider.

- Central coordination will determine success.

- The deal will span many years.

We have identified five techniques that, when executed successfully, address some of the most challenging aspects of large, complex outsourcing deals.

Embed government people with the provider. Almost all outsourcing contracts include opportunities for interim reviews. However, these rarely meet all the needs of either the government or its providers in terms of two-way information flow, monitoring of the customer’s experience, and mitigation of future risks. One way to correct this is to embed people from the government within the provider organization, a setup that can provide real-time feedback and enable midcourse corrections.

The U.S. government uses a form of embedding in its outsourced research facilities. Federal employees (including members of the armed forces) are deployed on temporary assignments to federally funded R&D centers, such as the RAND Corporation and Los Alamos National Laboratory. The development of working relationships and insider knowledge improves the effectiveness of the outsourcing arrangement over the long term.

Maintain some of the outsourced activity in-house. Outsourcing should not necessarily mean the elimination of all in-house capability for delivering a service. When a provider’s service quality is hard to measure objectively, or when the arrangement is likely to create dependency on the provider, keeping an in-house “echo” of the outsourced capability can make sense.

The U.K.’s Department for Work and Pensions, for example, maintains a network of Jobcentre Plus branches to administer unemployment and other benefits, as well as to provide advice and support for job seekers. These centers coexist with a series of initiatives that involve private- and social-sector organizations in the delivery of back-to-work services. According to an Institute for Government report, the retention in-house of the Jobcentre Plus “backbone” allowed the government to respond much more quickly to unemployment spikes after the recent financial crisis than would have been possible had the service been entirely outsourced.

Exercise control. In-house services at most organizations are run through command-and-control hierarchies. That style doesn’t work with outsourcing arrangements, making it tougher for governments to provide central coordination, ensure that key requirements are met, and mitigate risk—especially political and reputational risk. A smart approach is to determine what the government needs to keep under tight control and where it should let the supplier run loose.

The U.S. Department of Defense operates a highly advanced form of central coordination with its 13,000 contractors. To be entitled to handle classified data, providers must, among other things, sign a legally binding set of guidelines on systems and processes that they are mandated to have in place at their sites. On top of that, any IT system used to handle classified information must be certified and accredited by a separate government body.

Then there is the challenge of ensuring that key needs are consistently met. While well-drafted contracts can largely address this, retaining a degree of direct operational control can be an important tool. The U.K.’s Department for Work and Pensions, for example, needs to be sure that the contractors it pays to provide job search assistance are not cherry-picking the easiest cases. The department therefore runs all referrals through its network of Jobcentre Plus branches, allowing it to control the flow of cases to contractors.

Finally, there is the issue of mitigating risk, such as a hit to the government’s reputation. Here public-sector leaders are taking a page out of the playbook of private companies. The U.K. government is attempting to create a customer rating system, along the lines of travel site TripAdvisor, to evaluate companies that provide cloud services to public agencies through the government’s G-Cloud purchasing site. Recognizing the potential for problems from the posting of unmoderated comments, the government is developing alternative metrics to rate providers based on the number of contracts they have won and their past performance. This sort of vetting will hopefully help the government avoid procurement embarrassments.

Build transparency and trust. In the case of long-term contracts, both governments and providers are frequently expected to invest in training, equipment, R&D, and new systems and processes. Although the level of investment and the output required are often specified contractually, the requirements can change over time, leaving both parties exposed.

An effective relationship between government and providers depends on both parties trusting that they will benefit from the contract on an ongoing basis. One way to achieve this trust is to tie the organizations together. The U.K.’s Cabinet Office took this approach to the outsourcing of the Civil Service’s pension administration. The managing entity, called My Civil Service Pension (MyCSP), was spun out as an independent operation and is owned by a group comprising former government staffers (the new operation’s managers), the government, and a private management company. This joint ownership creates a strong, ongoing relationship among all three groups.

A different approach has been tested in U.K. public-sector construction projects. Under this model, primary contractors on projects such as prisons and schools are appointed before the final price has been agreed upon. Negotiations with second-tier suppliers are then conducted jointly by the government and the contractor. This gives the government a clear view into supply chain costs and fosters trust between the government and the primary contractor.

Use on-demand purchasing. In some cases, complex, long-term deals can be made smaller and simpler through the use of pay-as-you-go services. The U.K. government, for example, has pioneered the use of on-demand cloud-based services via the Internet. Its G-Cloud initiative allows government departments to purchase cloud services, including IT infrastructure, software, platform, and specialist services, from approved suppliers. Most of these services are priced on a per unit basis, allowing agencies to purchase as many units as they need, when they need them.

Hong Kong’s government likewise used an on-demand purchasing model for outsourcing its online, one-stop-shop Electronic Service Delivery portal. The government pays the provider according to the volume of chargeable transactions made by citizens through the site.

Getting a Good Deal for Government

Outsourcing is of increasing interest to cash-strapped public authorities worldwide. But given the mounting complexity of the services being outsourced, these deals can just as well destroy value for the public sector as create it.

Critical to achieving positive results is building a strong relationship with the provider organization. While contracts play a very important role, they often are not sufficient. Government officials need to decide if the service they are outsourcing is critical, the deal long term, the outcome hard to measure, the needs and costs unpredictable, and central coordination desirable. In cases where at least some of these conditions exist, they should invest in a range of smart approaches that build closer ties, retain or develop know-how, and improve flexibility.

If only he had employed some of these techniques, Hanno the Great, supported by his Numidian military-service providers, might be remembered as the vanquisher of Rome and not just as another defeated Carthaginian.