Corporate transformation—the end-to-end reinvention of a business—is often seen as a last-ditch undertaking. Too many retailers, especially those with long track records of success, look to transformation only after their business models begin breaking down or when they are unable to compete. Declining sales, rising costs, disgruntled customers and employees, competitors of all kinds stealing market share, and the emergence of nontraditional business models threaten to overwhelm these companies. The big question is often whether they can survive long enough to reverse momentum and address the issues necessary to survive. The answer, of course, is often no—the bankruptcy graveyards are full of once-storied defunct retailers.

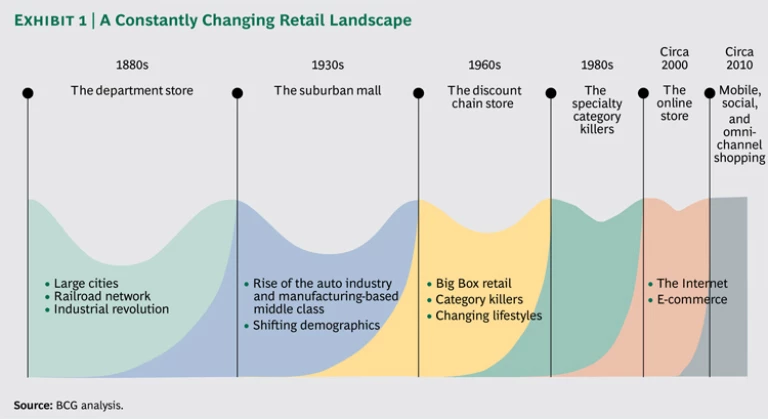

The cycle of change in retail today is accelerating faster than ever, thanks to a host of increasingly nimble challengers. Grocery and mass-market retailers, especially, find their traditional turf under attack from all sides. Successful companies can’t afford to rest on their laurels. Branding and familiarity are formidable forces, but customers do switch over time—and sometimes rapidly—when offered a superior value proposition. Price, assortment, and convenience can still be powerful competitive criteria, but they are becoming progressively commoditized by the Internet. Service, quality, value, and experience are critical differentiators today—and they are being exploited by a host of deft competitors, both online and offline. These qualities require constant reinventing by grocers and mass-market retailers that want to stay relevant to their customer base, much less capture share from the chain across the street—or in the cloud. (See Exhibit 1.)

Regardless of segment or circumstance, retailers can benefit from considering an end-to-end change agenda. Those seeking the next phase of growth can use the transformation process to embrace new offerings, categories, formats, and channels, or to expand into new markets and territories. Companies in fast-growing markets can stay ahead of the curve, making sure they have the capabilities they need to maintain customer satisfaction and build lasting relationships. Transformation can also offer companies in strong but trailing positions the opportunity to leapfrog to leadership.

Much has been written, including in our own publications, on the digital revolution in retail, but less has been offered on the continuous need for traditional retailers to transform their bricks-and-mortar businesses. Transformations must reinvent not only the in-store experience for consumers, but all the components that contribute to this experience, including store mix and format, people, products, infrastructure, IT, and supply chain, to name a few. There’s no question that creating an attractive, profitable, competitive omnichannel experience for consumers is one of the biggest challenges facing most companies today. So much so that even some online players have started building stores on street corners.

Traditional retailers face other, even more immediate challenges as well. The financial crisis and the resulting Great Recession altered consumer sentiment in many markets. Discounters capitalized, taking significant share by reinventing business models to meet changing times, improving quality, and providing fresh goods to their grocery segments.

This report looks at how transformation can help grocers and mass-market retailers—through the lens of getting the real-world aspects of a company’s operations right. We argue that most traditional retailers face an increasingly urgent need to reinvent multiple aspects of both the front and back ends of their businesses to ensure that their models are competitively viable today and sustainable for the future. In increasingly competitive markets around the world, with the lines blurring among such historically distinct segments as grocery, mass-market, and discount—customers are fickle. Even the most engaging offering, whether it involves one channel or several, will come up short if the rest of the company is ill-prepared to deliver on its promise.

The initiatives that constitute a full transformation program can be divided into three categories: funding the journey, winning in the medium term, and building a sustainable operating model for the long term—especially the right team, organization, and culture. The near-term steps to raise cash need to be taken with their longer-term consequences in mind. Medium-term victories are the result of near-term decisions. Building the right team, organization, and culture begins on day one.

Funding the Journey

A quick start helps to put a company on the right road. Retailers in transformation need early wins from near-term actions, such as cost reductions or short-term improvements in sales performance, to establish credibility and generate momentum. These steps also raise cash to fund the journey by paying for longer-term investments or initiatives without requiring shareholders to adjust their earnings expectations. Perhaps most importantly, they put a favorable wind at the company’s back, demonstrating to employees, investors, and others the seriousness of the effort and the fact that management has a road map for success.

There are many places to begin. One European retailer, operating multiple formats in several countries, amassed a war chest of more than €200 million in the first six months of its transformation through a combination of cuts in administrative overhead, cost of goods sold (COGS), and goods not for resale (GNFR). The company negotiated new deals with suppliers, especially multinational and large national consumer-goods companies, established a new GNFR-purchasing organization that used a new approach and tools, and took a number of steps to restructure and rationalize its headquarters functions.

This retailer generated an even stronger tailwind by launching a number of actions to drive like-for-like sales in the near term, including a new promotion and pricing scheme, “come back” coupons to encourage repeat visits, redesigned “power” aisles featuring changing promotions and weekly themes near the entrance of its stores, and a program to enhance customer service. Its actions caught the attention of the market and rekindled interest among consumers. The company turned around declining sales and increased its market share by more than 1 percent within the six-month period. Moreover, the combined results of these efforts, as is often the case, were not only improved sales and significant savings but also a leaner, more agile organization more clearly focused on reinvesting in its brand promise and customer experience.

Another retailer, on the other side of the world, is well on its way to generating more than $1 billion in savings and new revenues through a combination of initiatives in multiple areas, including COGS, markdown effectiveness, GNFR management, total loss savings, and a rethinking of supply chain management.

These are far from isolated examples. Many retailers can deliver quick and significant cuts through similar efforts. In our experience, a typical vendor-management program alone, for example, takes about six to eight months to implement and can yield 200 to 300 basis points of improvement in gross profit margin.

Fixing operational inefficiencies begins with thinking about inventory management and profit maximization from the perspective of total loss, that is, the sum of product waste, shrink, and markdowns. This is one of the basic tenets of a “lean” approach, from which most retailers can benefit. We have found, for example, that in-store processes are responsible for approximately two-thirds of all product loss.

Operating in a lean retail environment also includes improving labor productivity and optimizing the flow of product to minimize out-of-stock items while maximizing inventory turnover. Low-cost operators create an essential, sustainable base of long-term competitive advantage. An in-depth, data-based approach to eliminating the root causes of suboptimal productivity, inadequate product availability, and waste can boost the bottom line while improving service levels and customer experience.

Potential steps to reduce total loss include improving coordination with suppliers on product waste and pack sizes, rationalizing high-waste SKUs (for those selling fresh food or other perishables), developing the right algorithms for order management and replenishment, and optimizing the ratio of floor space to sales. Initiatives such as these have led to hundreds of millions of dollars in cost savings and revenue increases for individual retailers in the form of improved product availability and sales, reduced total inventory, reduced loss, faster inventory turns, and lower labor expenses. They have also improved employee engagement and overall customer satisfaction.

We worked with one supermarket chain, for example, to comprehensively reduce total product loss by 40 percent. For a North American retailer, we delivered almost $300 million in year-over-year savings, including $150 million in labor savings without adversely affecting quality of service. We helped another retailer reduce inventory by 20 percent while almost doubling product availability. (See “Increasing Sales by 80 Percent in Eight Months.”)

Increasing Sales by 80 Percent in Eight Months

A large Asian food and grocery retailer with some 500 stores sought to stem losses and increase sales per square foot by undertaking operational improvements and designing a new store concept. The existing stores suffered poor infrastructure, low product availability, and cluttered and unattractive displays.

The early stages of the company’s transformation program were designed to register quick wins. A new category strategy focused on increasing sales, especially in produce and bakery. The company improved product displays and in-store navigation and upgraded store infrastructure overall. It analyzed and improved its inventory-flow management system, designed new marketing and promotion campaigns, overhauled training, and increased staff strength and salaries to improve customer experience.

Within eight months, sales per square foot jumped 78 percent. The company registered more than 1,000 basis points of net profit improvement at the store level. Product availability increased by 10 to 15 percent. The company is now on a realigned path to profitability, driven by top-line growth and improved operating leverage.

One important step is putting in place operational and financial reporting mechanisms that enable all managers to see the impact that the changes being implemented are having on key metrics of the business. Such tools show an all-important internal managerial audience that the transformation is working and that their actions are part of its success.

In an age of near-total price transparency, providing value for money (and getting credit for that value) is an essential foundation. Pricing strategy needs to be clearly aligned with business strategy at all levels—that is to say, at the market, store, category, channel, and customer levels. But it’s important to remember that price is only one component of value.

Many initiatives that can be implemented in a matter of months or even weeks can drive real increases in traffic, sales, inventory turns, and profit. Examples include:

- Redesigning promotions

- Creating an ideal range of products (assortment)

- Optimizing price gaps among brands (and between name brands and private-label products)

- Implementing “price laddering” to encourage customers to save money by buying larger sizes

- Using key value-item pricing

- Offering “come back” vouchers or coupons

- Establishing targeted promotions to drive traffic and margin among a store’s most profitable customers

- Creating an effective loyalty program.

It can also pay to take a fresh look at the fundamentals of customer service. Simply making sure checkout lines don’t exceed a specified number of shoppers or a set wait time can send a powerful message to customers and employees alike that change is afoot.

Winning in the Medium Term

If journey-funding initiatives can be described as quick hits, medium-term undertakings are designed to create institutionalized change in a company. They establish improved and enduring processes and drive a renewed and differentiated value proposition for customers. Medium-term strategies—which can include continuation and expansion of the supply chain, lean operations, product, category, pricing, and promotional levers of the initial funding stage—are what put a company on a trajectory to grow sales, expand margin, and deliver a winning concept.

A European grocer, for example, set a goal of “doubling value by 2017,” which called for it to increase revenues by more than 15 percent over its pretransformation plan and boost market share, in a highly competitive environment, by at least two points. Initiatives included reinventing existing concepts, improving category management, establishing a new private-label organization, and accelerating international expansion.

These efforts take time: the medium term usually means three to five years. Substantial investment is often required. The funding created earlier on in the process helps support the initial stages of the structural change until the benefits flow through to profit. A large grocer codified its complex program into a six-point strategy that addressed the critical issues it faced: value, quality, store operations, product availability, service with personality, and ultimately, “the best customer experience.” It established month-by-month plans covering two years with detailed milestones in 15 separate areas, including both strategic initiatives such as format development and service improvement and individual store departments such as produce and bakery. Consequently, the company has seen sales grow at an annual rate of more than 5 percent for the past several years, a double-digit increase in average basket size among customers, and a multibillion-dollar increase in incremental revenues.

For most grocers and mass-market retailers, the issues addressed fall into four areas:

- Store Format and Footprint. This includes store renewal, new format development, and network strategy.

- Category Strategy. This includes category development and extensions, private-label strategy, and value strategy.

- Customer Engagement. This includes brand development and loyalty program development.

- Omnichannel Strategy. This calls for designing an offering that combines bricks, clicks, mobile, and social networking—and enables customers to engage and shop using the channel of their choice.

Store Format and Footprint. For traditional retailers, the store format and the footprint of the store network will continue to be the critical determinants for reaching customers. While many companies have an online presence and perhaps a mobile capability, a key role for their digital initiatives is often to drive traffic to stores and provide an enhanced, theatrical, and differentiated shopping experience across all channels.

Throughout the various segments of the retail industry, we increasingly have seen a race by followers to catch up to segment leaders—companies that have spent years developing concepts that provide an incredible customer experience while also making money. Everything about these leaders’ stores—their “look and feel,” their location, the merchandise on offer, the advertising campaigns—promises and delivers on a winning combination of value and experience. The physical design and layout of a store must deliver an end-to-end experience that satisfies the customer’s needs, makes him or her feel valued, and inspires repeat visits. This results from a combination of factors, among them architecture, interior and exterior displays, ambience, traffic flow, sightlines, and navigation.

Too often, companies make big investments in mimicking the best-in-class players by building and fitting out elaborate stores that are full of superficial (and expensive) bells and whistles that they believe their customers want. Too many format changes cost too much money, and even though they may result in an uplift in sales, the company has little chance of recovering its capital costs. All too little time, attention, and money are spent on the more difficult, legitimate drivers of experience and value. When companies fail to get those right, customers will quickly see through the fancy veneer to the flaws behind.

Retailers are better served by focusing on several fundamental questions:

- Does the current store format truly meet the needs and demands of the customer?

- Has any renewed format been tested and re-engineered sufficiently to ensure that it delivers the new proposition at a capital investment that will achieve return on investment (ROI) targets across the chain?

- Are the stores the right size to carry the assortment efficiently and profitably?

- Are the stores of the right density to optimize customer acquisition and unit economics?

- Are they in the right places to serve customers effectively?

- Does the business also meet customers’ needs for multichannel access to the products on offer?

- Does the company need to integrate digital or mobile capabilities and services such as in-store Wi-Fi or online terminals to expand virtual inventory, home delivery, click-and-collect services, or parcel lockers for drive-through pickup of goods ordered online?

- Does the company’s service deliver what it is promising the customer?

- Does the quality of merchandize meet customers’ expectations, particularly if these expectations have been raised?

- Can the supply chain support the new proposition?

Category Strategy. Clarifying the role of product categories is critical to achieving two potentially conflicting goals: maintaining customer loyalty and lowering the cost of goods. Precisely curating the product assortment, determining the extent of private-label penetration, and developing a loyal and effective supply base should be high on agenda of the CEO and the chief merchant.

Retailers need to make choices. The temptation is to give customers as much selection as possible, but store-based retailers cannot compete with the ability of online marketplaces to provide near-endless assortment. (Amazon lists more than 2,800 SKUs of facial moisturizer, for example.) Moreover, “overassorting” can exhaust customers. Multiple studies have shown that too much choice overwhelms shoppers while it also complicates the supply chain and increases working capital expense (by causing the merchant to carry too much inventory that does not turn quickly enough). Companies can reduce inventory, labor, and the cost of goods sold by reducing the number of SKUs and suppliers. They can then negotiate with the remaining suppliers for discounts based on buying and selling larger quantities of fewer products in a more targeted and effective manner.

Curation does not mean narrowing the customer experience, however—in fact, quite the opposite. Traditional retailers can become a destination for a particular category by offering the best assortment and expertise available. They actually have a big advantage over their online competitors: in their stores, they have the ability to offer a compelling experience that includes expert, personal service and the ability to try products out or on. To match the online depth of assortment, retailers can offer a selection in stores and an expanded assortment online. In a store, customers can see and feel products, ask questions, and—if their chosen style or size is not in stock—even order online. The trick is to make smart decisions, rooted in economics, about the range of products offered in each channel and how the various channels work together.

Customer Engagement. Brands are powerful drivers of business. They are often the reason why people shop where they shop. Consumers know exactly what to expect from such retailers as Whole Foods Market, Wegmans Food Markets, or Costco in the U.S.; E.Leclerc in France; Mercadona in Spain; or 7-Eleven in Japan. Brands are also delicate; missteps can do damage quickly and take much more time to correct. Most mistakes have been rooted in the failure to deliver a clear customer value proposition (CVP). Several major retail transformations in recent years have stumbled when the companies tried to change major components of the CVP without undertaking a corresponding branding campaign designed to maintain the trust of core customers. These errors have resulted in widespread disappointment and defections.

Transforming a retail brand requires engagement with customers that is based on both rational and emotional hooks. Companies earn and maintain trust by communicating honestly in a timely and precise way. The first step is to make sure that management throughout the company has a solid understanding of how functional benefits tie to emotional benefits and to the brand perception and relative market share by customer segment. Senior leaders can then identify where market share deviates from perception—and the optimal spaces for the brand to play in. This becomes the basis for the new brand positioning.

A key component is defining a brand strategy that provides guidance on how to effectively deliver the brand promise to consumers. Companies often neglect the fact that they need to bring their customers along the way, educating them on why the new brand is better. They cannot assume customers will figure this out on their own. Most people don’t like change; they prefer familiarity and comfort. Where trust exists, therefore, you have to invest wisely to maintain and build on it.

Omnichannel Strategy. As we have written in previous BCG publications, increasing market complexity and heightened consumer expectations mean that retailers must have a strong, dynamic multichannel strategy. They need to be absolutely clear about whom they’re targeting, what value proposition they’re offering, and what their competitive advantage is—especially since consumers are bombarded by choice. As consumers become more comfortable buying online and on the go, they also become “channel agnostic.” That means shoppers don’t “pick” a channel within which to conduct their business. Instead, they tend to use a mix of online and offline channels as they move through the purchasing process, and they may not even be aware of which channel or channels they use. Retailers must continually experiment and learn, revisiting and revising their positioning and capabilities in order to stay relevant. Standing still is not an option in this rapidly changing industry.

BCG has published numerous recent reports and articles on omnichannel retailing and the impact of digital, mobile, and social media on the industry. See, for example, Retail 2020: Competing in a Changing Industry , The Omnichannel Opportunity for Retailers , The Millennial Consumer , and How to Approach Social Media Commerce.

Building the Right Team, Organization, and Culture

The right strategy, the necessary funding, and excellent execution are all essential, but no transformation will succeed without the right team leading it. The CEO must be fully engaged, otherwise the organization will certainly falter. He or she sets the tone—the urgency—of the undertaking and maintains ultimate accountability for its success. In a company of any size, he or she also needs help in carrying that message through the organization. Transformations are a team effort, but the push for change, the rationale, and the vision must come from the top.

Most companies also need to recognize the need to acquire new capabilities and skills in their management ranks. Outside help, often at the most senior levels, is almost always required to move transformations forward. One reason is the need for a fresh mindset—senior executives who are free of organizational “baggage.” Another is experience—any company can benefit from people who have been through transformations before and have already dealt successfully with the issues that arise. Large organizations may have people with relevant experience who they can move into key roles, but there often is not time to develop the necessary skills and capabilities internally—these must be recruited from the outside.

Before embarking on a major transformation, the CEO of one multibillion dollar company told the assembled team of executives, “This business will be unrecognizable when we have finished.” He was true to his word. For one thing, there was a different group of executives in the room when they met to review progress—a predominantly new team was running the business. For another, the products, the stores, the value proposition, the quality, and the capability of the organization changed beyond recognition. The company went on to treble like-for-like sales growth and double both EBIT and return on capital in four years.

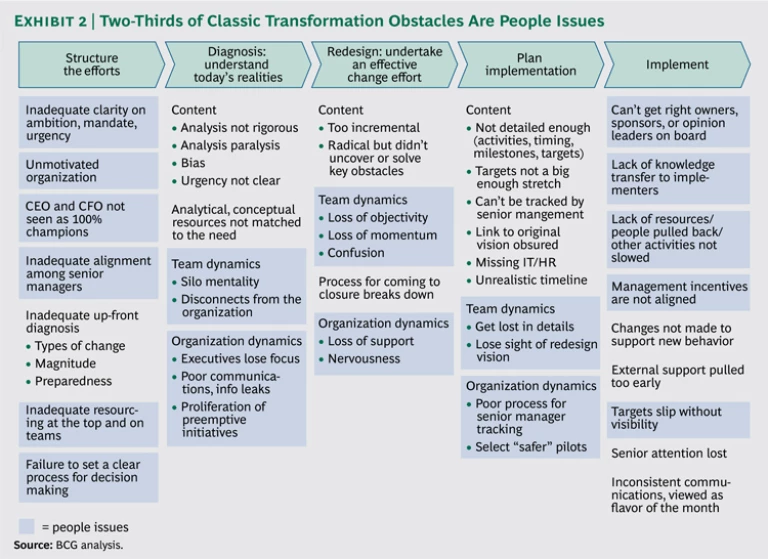

In any company, there are many obstacles blocking change. In our experience, two-thirds of the most common obstacles involve people. (See Exhibit 2.) Yet certain approaches can overcome these barriers; we recommend that companies immediately embrace the following four:

- Reconfigure the CEO’s calendar to focus substantially on the transformation during its first year.

- Get the right composition for the executive leadership team; make sure all the senior team members are committed to the need to change.

- Put the right people in the roles that create the highest value throughout the organization so that they can help accelerate the transformation. Shed toxic talent that laments change or longs for the “good old days.”

- Start developing an internal and external pipeline for new talent. As part of this step, identify key capabilities the company will need and may not yet have.

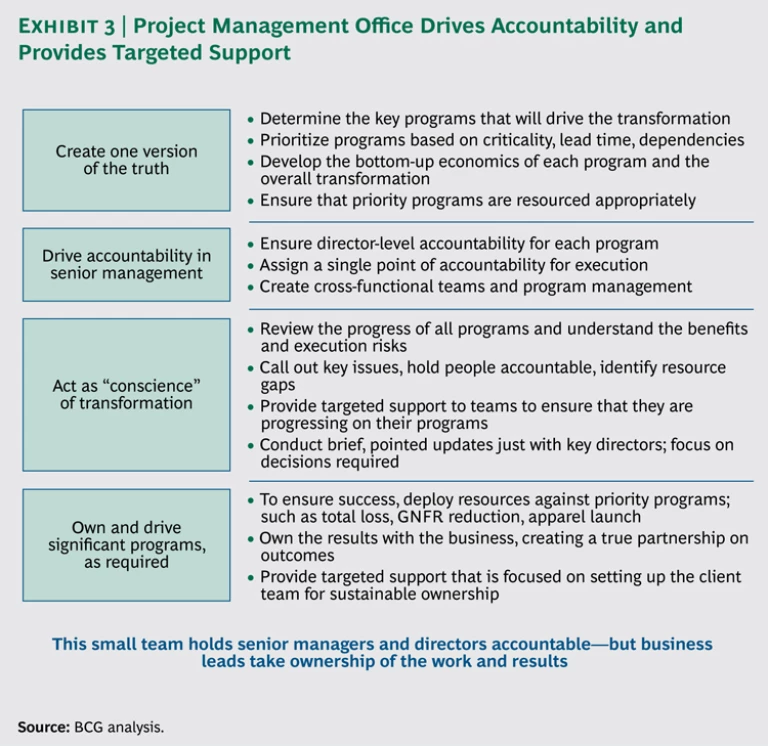

Many companies establish program management offices (PMOs) to—in the words of one executive—“act as the conscience” of the transformation. PMOs are given responsibility for overseeing the change management program, including planning initiatives, tracking and reporting execution progress, assessing and aligning talent with those initiatives, conducting regular employee pulse-check surveys, and communicating regularly with the top leaders in the organization.

A PMO should never manage the projects of a transformation; the responsibility for implementation and reaching milestones must reside with the relevant line managers, otherwise accountability is undermined. Instead, the PMO oversees the overall change program and is empowered to hold senior management accountable for its progress. (See Exhibit 3.)

A big mistake made by many managements that undertake transformation programs is taking an eye off the day-to-day performance of the business. Establishing and monitoring the right key indicators in such areas as store format, product category, and store performance is essential. These are also easy to overlook while new initiatives are getting under way and new people are joining. But once management starts to slip on tracking and taking steps to address issues in daily and weekly performance, the company can quickly lose momentum, putting the transformation program at risk.

Without the full support of the organization at all levels, the best redesign in the world—of brand, store, category, value, or cost—will also be destined to falter. At the top, the board of directors needs to allow enough time and flexibility for the change program to take effect. Sometimes, at the store level, employees can easily feel threatened and confused and fear for their jobs—at the same time they are serving customers. Therefore, everyone needs to be brought—and kept—on board with highly transparent, frequent, consistent, two-way communication that apprises people of progress and celebrates collective success.

Soliciting—and acting on—feedback, especially from the front lines of customer interaction is an essential tool. The PMO can help coordinate these efforts, but effective, two-way communication and feedback need to be ingrained into the culture of the new organization.

There’s No Time Like Now

Transformation and reinvention can be powerful tools for any company looking to keep pace—or stay a step ahead of—a changing marketplace. All retailers can benefit from a periodic, hard-nosed assessment of where they stand in a shifting competitive landscape. Declining share, slower store traffic, and falling sales could be temporary aberrations, but in today’s retail environment, they are likely indicative of bigger, long-term shifts.

The CEO of a leading technology company frequently says that his company’s success lies in getting market transitions right by understanding what they mean to the customer. The same can be said for retailers. Competitors may take a point or two of market share, but big changes in the way people shop can undermine the entire foundation of a company. Transformations are not for the timid—but remember all those defunct retailers. Those companies that recognize—or better still, anticipate and lead—the marketplace transitions taking place, are giving themselves the opportunity to drive change for the benefit of investors and employees, rather than letting changes in the marketplace drive them to the brink of extinction.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Chris Biggs for his insights.