It’s a well-known mantra in business: “You can’t cut your way to greatness.” Nonetheless, painful cost cutting and other defensive measures are a familiar strategy for staying afloat. They are quick and obvious and deliver tangible results, but they are not in themselves a recipe for success. What does a CEO driving a turnaround do after these “easy” measures have been exhausted?

In an era in which markets are more turbulent and leadership is less durable, companies must continually renew their competitive advantage. (See “ Adaptability: The New Competitive Advantage ,” BCG article, August 2011.)

It is not surprising that an increasing number of companies find themselves out of step with market realities and in need of transformation. As Xerox CEO Ursula Burns said in May 2012, “If you don’t transform your company, you’re

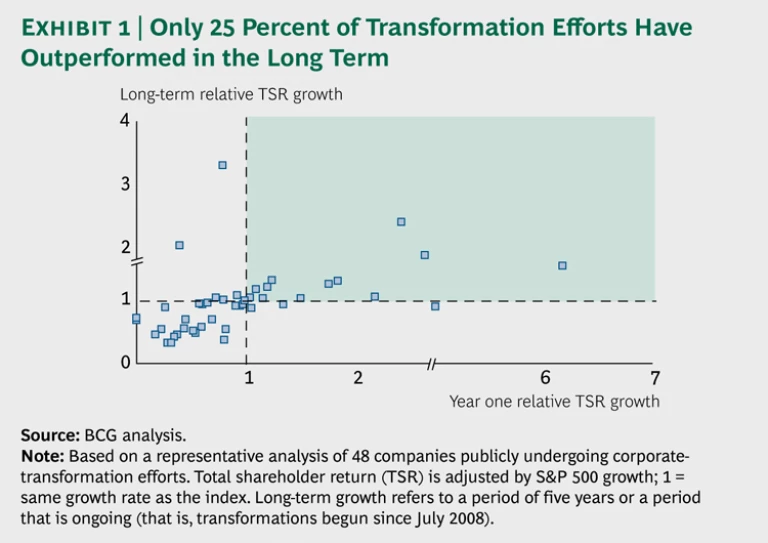

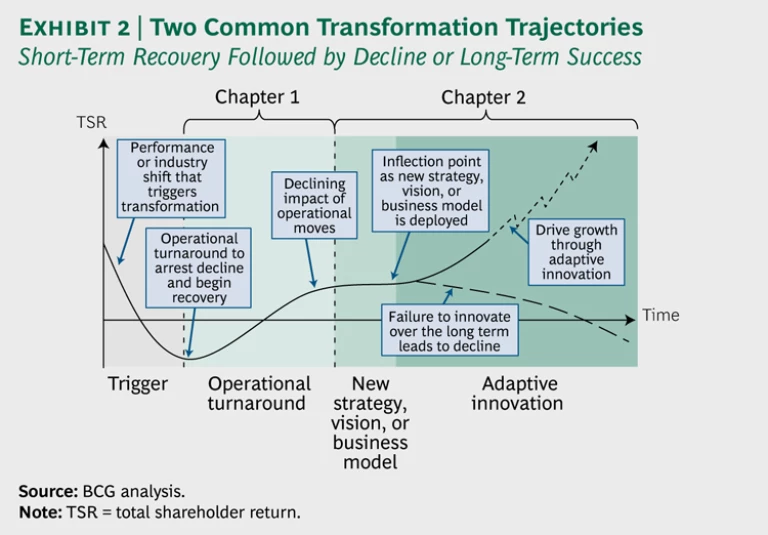

We looked closely at the long-term performance of transformation programs by using the method of paired historical comparisons, an approach that eliminates interesting but irrelevant details and zeroes in on the key factors that separate success from failure. We studied a dozen pairs of companies, each in the same industry and facing similar challenges at similar times. Our study revealed two common trajectories: short-term recovery with long-term slow decline and, less commonly, short-term recovery with long-term restoration of growth and performance. (See Exhibit 2.) So what’s the formula for the second path?

Chapter One: The Turnaround

In theory, companies could preemptively or continuously transform themselves, but that is not often what happens. All the examples we studied had a first phase of cost cutting and streamlining—triggered by a decline in competitive or financial performance—which we call chapter one of transformation. In chapter one, the fundamental goal is to do the same with less.

Chapter one does seem to be an essential component of transformation; we didn’t find a single successful example that didn’t go through this phase. Streamlining reduces inefficiencies, buys time by addressing short-term financial woes, and frees up resources to fund the journey toward future growth. A typical chapter one lasts up to about 18 months and is usually successful in restoring total shareholder returns to sector parity levels. The main mistake that some companies make during chapter one is not cutting boldly enough at the outset, which can trigger painful, repeated rounds of cost cutting and undermine morale, momentum, and leadership credibility.

Chapter Two: Creating Lasting Change

For successful transformers, though, the story doesn’t end there. Of the companies we studied, those that thrived all had a distinct second phase of transformation: chapter two. Whereas chapter one primarily addressed costs, chapter two focused mainly on growth and innovation. In chapter two, successful companies went beyond necessary but insufficient operational improvements and deployed a new strategy, vision, or business model that they refined over a multiyear period.

Transformations don’t follow a cookie-cutter model; they need to reflect the challenges unique to each situation. Nonetheless, we identified eight factors that drive long-term success:

- Turning the Page. Companies make a conscious decision to go beyond the efficiency moves of chapter one and refocus on growth and innovation.

- Creating a New Vision. Companies articulate a clear shift in strategic direction, coupled with room for experimentation.

- Foundational Innovation. They innovate across multiple dimensions of the business model, not just in products and processes.

- Commitment. There is persistence from leaders in the face of inevitable setbacks and internal opposition to unproven shifts in strategy.

- Imposed Distance. There is a willingness to shift from the historical core business model and its underlying assumptions, often by creating a deliberate degree of separation between the new business model and legacy operations.

- Adaptive Approach. Transformation unfolds through trial and error, with ongoing refinement of a flexible plan.

- Shots on Goal. Companies do not pin growth hopes on a single move but rather on deploying a portfolio of moves to drive growth.

- Patience. There is adherence to the vision over a multiyear period.

But what about those that try to transform but fail? Many companies run into several of the following traps, which are surprisingly obvious yet seemingly difficult to avoid:

- Early-Wins Trap. Companies declare premature victory after chapter one and fail to declare or develop a second chapter.

- Efficiency Trap. They continue with multiple rounds of cost cutting and efficiency improvement measures.

- Legacy Trap. They fail to shed core assumptions and practices even when they are self-limiting or no longer relevant.

- Proportionality Trap. They make promising moves—such as a series of new business pilots—that are not proportionate to the scale of the challenge. “Dabbling” was a surprisingly common differentiator between the successful and unsuccessful companies we studied.

- False Certainty Trap. They believe that the course of action can be rigorously planned in advance, and they overemphasize disciplined implementation of a fixed plan instead of continually iterating in response to new knowledge.

- Persistency Trap. Companies underestimate the time needed to see results (often up to a decade), and, consequently, they let up too soon.

- Proximity Trap. They undermine the new business by keeping it too close to the core business, even when that closeness triggers competition for resources or conflicting assumptions.

Chapter Two in Practice

A close read of select case studies illustrates how chapter two can drive success or failure. The Australian airline Qantas’s creation of JetStar demonstrates a successful transformation through foundational innovation. Kodak illustrates the perils of a missed opportunity for a strategic turnaround. And IBM exemplifies how transformation must be managed over an inconveniently long time horizon.

A New Route for Qantas. In 2000, two low-cost carriers disrupted the Australian domestic-aviation market—a historic duopoly controlled by Ansett and Qantas. Twelve months later, Ansett collapsed and Qantas, a traditional airline with a high cost structure, was losing share. From 2003 to 2010, however, Qantas’s TSR outperformed both the market and the sector. How?

Qantas first commenced a transformation program to streamline operations, cutting $1 billion in costs over two years. Qantas then layered on chapter two—a fundamentally different business model—with its launch of Jetstar, a wholly owned, no-frills, low-cost carrier. Today, Jetstar is a core driver of Qantas Group’s profit.

Chapter two worked because Qantas stayed focused on a key success factor for low-cost carriers: high-asset utilization—that is, maximizing the hours a plane operates, which enables the airline to charge lower fares. Qantas kept Jetstar’s network and value proposition intentionally separate from its full-service offering, and it branded Jetstar distinctly for the leisure traveler. With its own fleet and profit-and-loss statement—and interactions with Qantas only at the board level—Jetstar flourished unencumbered by the legacy organization and cost structure. Further, a leadership team drawing heavily on external talent brought fresh thinking, flexibility, and a cultural shift to enable the new model.

International competitors undertook similar cost-reduction and low-cost-carrier launch efforts. But by the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century, many such ventures were grounded. Falling into several of the common transformation traps, these new ventures were often too encumbered by core business cost structures or thinking to be effective and viable.

Kodak: A Missed Photo Op. Few brands were as synonymous with their industry as Kodak. So it was a sad end of an era when the company filed for bankruptcy in 2012. Kodak made a genuine effort to transform; it just didn’t do so thoroughly or nimbly enough. In early September 2013, the company emerged from bankruptcy but as a much smaller operation with an unclear path forward.

Kodak’s chapter one was characterized by multiple, insufficient rounds of cuts and layoffs, steps that degraded morale and failed to attract talent to fuel innovation. At the same time, even though Kodak had clearly identified a compelling opportunity—a shift to affordable digital cameras—it did not allocate sufficient resources to develop and expand this new strategy. Falling into the persistency trap, Kodak stifled new projects that did not meet the benchmark economics of its existing legacy film business. The culture of the legacy business prevailed with digital efforts integrated within the company, leaving Kodak ill-equipped to shift to a new business model.

IBM: Updating the Operating System. IBM’s transformation is compelling for the persistency and success of its chapter two efforts. Since Big Blue embarked on a full transformation two decades ago, the company has undergone a chapter one operational turnaround; adopted a new strategy, business model, and vision; and—most critically—supported adaptive innovation despite changes in leadership and the environment. Three CEOs and two market crashes later, IBM’s revenue has nearly doubled.

IBM engineered continuous transformation into its organizational DNA. Management displayed a clear vision for the future, pragmatically shifting its business toward high-margin services and software while shedding the lower-margin, lower-growth hardware business. The company ensured many shots on goal by empowering teams to innovate and build new businesses through a structured process, including incubating emerging business opportunities under separate management. And leadership has taken a long view and communicated it actively, going so far as to share four-year financial roadmaps with investors and analysts.

The most important lesson CEOs should learn from IBM’s transformation is that the job of sustaining growth and innovation is never done: IBM doubled down again on software and services at the end of the last decade and plans to spend $20 billion on acquisitions between 2012 and 2015 to drive growth.

Transformation Paradox

In our study of transformation efforts, we see a remarkable paradox. The pitfalls of transformation are unsurprising, the payoff from doing things right is significant, the goals of transformation are clear—and yet organizations repeatedly fail to follow the right path to success.

There are multiple plausible reasons for this. For one thing, short-term cost cutting is easy and provides immediate rewards—and it’s tempting to believe that more of the same will yield more of the same. In addition, risk taking may seem unpalatable at the very moment you are grasping for stability. Leaders can be uncomfortable making the abrupt shift from cost cutting to the discipline of a growth strategy. The key to new growth will almost by definition seem counterintuitive—especially to the architects of the current business model. Indeed, the two chapters require very different leadership styles and capabilities, one more top-down and operational and the other more creative and empowering.

Leaders on the cusp of a transformation, therefore, need to embrace some inconvenient truths. Transformation demands attention to both the short term and the long term, to efficiency as well as innovation and growth, to discipline and flexible adaptation, and to clarity of direction and empowerment. Successful transformation requires an ambidexterity of leadership, one that resolves these apparent contradictions and navigates the company successfully through both chapters of transformation. (See “ Ambidexterity: The Art of Thriving in Complex Environments ,” BCG Perspective, February 2013.)