There is a massive gap between the need for infrastructure investment around the world and the ability of governments to pay for those investments. Public-private partnerships, in which the private sector builds, controls, and operates infrastructure projects subject to strict government oversight and regulation, can help bridge that gap.

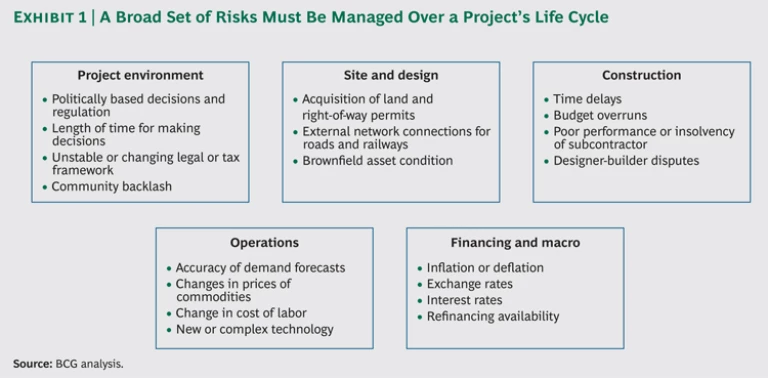

These partnerships, however, are often fraught with difficulty. For the private sector, the biggest challenge in creating successful PPPs is to identify and manage risk across the entire life cycle of a project. (See Exhibit 1.) Many of the risks are in addition to those found in publicly procured infrastructure projects, and they therefore pose particular challenges to private-sector companies.

- Project Environment. These risks arise from the political and legal environments in which the project operates. They include the risk of government decisions that are aimed at making users (and voters) happy but that penalize private-sector partners.

- Site and Design. These include obtaining the necessary permits and rights of way for construction and operation.

- Construction. Construction risks can be significant, particularly as projects become larger and more complex or involve new technologies.

- Operations. Given the long-term nature of PPP contracts, operations risks, such as the possibility that the demand forecast for a road or bridge turns out to be overly optimistic, are a real concern.

- Financing and Macro. These risks include the possibility that loans will have to be refinanced at rates that have risen higher than anticipated.

While there is no way to eliminate risk, BCG has identified six best practices that can help companies understand a project’s vulnerabilities and minimize risk where possible. This understanding not only allows for competitive bids and fact-based negotiations but also helps private-sector companies avoid contracts with unreasonable levels of risk.

Assess Risk Across the Entire Portfolio of Projects

A company should not bid on a project simply because it seems attractive. Instead, it should first see how the project fits into the overall risk profile of the company’s entire portfolio. Companies that take on large, complex projects but carry too much concentrated risk may run into financial problems.

This is particularly important today, with PPP markets concentrated in only a few countries, where debate about the PPP approach may be ongoing and where regulatory and legal structures may still be evolving. When deciding whether or not to take on PPPs in any given country, companies should examine the expected project pipeline of the country and sector, since setting up local teams and consortia, and conducting the initial legal and market due diligence, may incur large costs.

Consider developer funds, for example. These funds were established to free up cash from existing developments (by selling developed assets to the fund) and to provide financing for potential new developments. Pension funds and other institutional investors are attracted to developer funds because they consider infrastructure to be a long-term, low-risk investment that is hedged against inflation. Developer funds’ investment policies, therefore, usually define clear risk guidelines that are in line with their investors’ appetite for risk. The rules may specify, for instance, the maximum percentage of investments that may be made in construction projects and favor lower-risk brownfield investments, or they may specify the maximum percentage of the portfolio that any new asset acquisition can account for. And since many pension funds prefer to limit their risk with government-backed revenue sources, such as availability-based pricing models, the policies may also limit the share of assets that do not have government backing. (In an availability-based model, the operator of a toll road would pay for the provision of the road with a specified service quality, independent of the number of users traveling on that road—an arrangement that eliminates demand risk and thus reduces default risk.) Developer funds may also target a specific country because it has a track record of successful PPPs and is fiscally strong. Or they may focus on certain sectors, such as hospitals, schools or roads, to build up expertise in those areas.

Engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) companies can define their risk strategies similarly but with some modifications, such as including policies that specify the maximum level of exposure to a third-party contractor.

Manage Risk in the Bidding and Contract Negotiation Phases

Once it is clear that a project fits well in a company’s overall portfolio, developers must drill down and address the key risks associated with that project. This process involves three steps: identifying the risks, quantifying the potential impact of those risks, and prioritizing them to highlight the ones that should be given the most attention. The top five to ten risks, in particular, should be detailed for management, and the company should develop steps for mitigating those risks.

Many risks, including environmental, site, design, and operations risks, can be addressed while the contract is being developed or while the regulatory framework is being established. Though some governments are inflexible when it comes to contracts and regulation, others are open to a dialogue with private-sector partners, either through pre-bid conversations or during the final contract negotiation, on how to make the partnership a real win-win.

Private-sector companies might find it helpful to buttress their case with benchmarking information on PPPs from other countries. For example, in a central European country, electricity distribution companies conducted a detailed cost-benefit analysis and international benchmarking of the options for rolling out smart meters to residential customers. The companies shared the results with the government in a public review process and then, together with other stakeholders, agreed on a solution that helped guard the interests of both customers and private-sector investors. Customers were protected because the solution helped minimize the risk of rate hikes in the future. The private sector’s investors were protected because the solution clearly specified the conditions for smart-meter installation and thus saved the companies from executing investments that would yield poor returns.

In some cases, these conversations can result in risk-sharing arrangements. Such arrangements may include provisions to share the positive or negative consequences of fluctuations in demand for the asset or the refinancing of loans tied to the project, setting pricing that is indexed for inflation, and developing mechanisms for compensating the private-sector company for higher commodity prices.

The details of these contract and regulatory features should then be analyzed to evaluate what happens, under different scenarios, to the return that the private company earns. The analysis should include revenue-related factors, such as user price changes and ancillary revenues, as well as bottom-line and balance sheet factors, such as operating-expenditure cost changes or later-stage capital expenditure needs.

Finally, companies need to push back against government contracts that leave key details, such as the technical specification, unsettled or only vaguely defined. Companies need to spell out the unresolved issues and either clear them up before finalizing the contract or include contingency clauses that account for those uncertainties.

Select Partners That Can Fill Critical Needs

Companies should choose partners that fill gaps in the companies’ own expertise. Selecting the right partners can go a long way toward reducing a project’s overall risk, help deliver a project on time and within budget, and make sure that the specifics of the local market are properly accounted for in the plan. In most cases, local partners will include a local subcontractor that can deliver on public-sector goals, such as job creation. In India, for example, foreign road and airport concessionaires have teamed up with Indian construction firms in joint bids. Initial partnerships are usually nonexclusive and ad hoc, but they may evolve into more permanent and professionalized structures over time.

Control Construction Risk

Reports of high-profile infrastructure projects that have gone over budget or are facing major delays seem to surface daily. Construction presents major challenges, whether the project is an entirely new greenfield or an extension of an existing asset.

This is especially true in the increasing number of megaprojects, such as offshore oil and gas installations, next-generation nuclear power plants, and offshore wind farms. But it is also true for civil construction projects, such as the new Berlin Brandenburg airport, where problems with a complex, automatic fire-safety system and its regulatory requirements have delayed the project by more than two years.

There is no easy way to prevent such problems. But companies that adopt the proven best practices around all key aspects of large-project execution—from the initial design to commissioning—may be able to mitigate them. (See “Driving Success in Large-Capex-Project Management.”)

Driving Success in Large-Capex-Project Management

A myriad of potential landmines—from the complexity of a project itself, to swings in prices of commodities and other necessary materials, to getting access to key resources—lie in wait for project developers, owners, and contractors of large capital expenditure projects. Such challenges, however, can be overcome with the right planning. In our view, eight key action levers need to be addressed to ensure that projects are delivered on time and within budget.1 (See the exhibit.)

- Minimize capital expenditure requirements. Creating a cost-focused culture is critical. With a clear understanding of the drivers of cost, the needs and requirements of the end user, and industry best practices, managers can improve efficiencies and optimize project size to benefit from economies of scale.

- Design to deliver value. Contractors must understand the key drivers of value for their clients, such as minimizing upfront investment and long-term operating costs. With that in mind, engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) companies and EPC management companies can tailor their plans to meet objectives at the lowest cost possible.

- Apply vigorous risk management. As projects grow larger and more complex, establishing a process for managing risk becomes imperative. This includes defining acceptable levels of risk and outlining plans for minimizing risk whenever possible.

- Develop a program for efficient procurement. Poor procurement practices can have a damaging ripple effect on a project, driving up budgets and creating costly delays. To optimize procurement functions, companies must embed a number of policies into their operations, such as bundling purchases and obtaining materials from low-cost sources around the world.

- Optimize contracting strategy. To develop a solid contracting strategy, companies should analyze a project’s details and evaluate external market conditions, such as contracting trends among competitors. Developers should also have a disciplined process for selecting contractors, so that they can zero in on what truly differentiates the various bidders.

- Secure scarce resources and local content. Sometimes other ongoing projects in an area may compete for skilled labor and natural resources. Companies should determine the resources they will need and proactively plan for obtaining them in a tight market.

- Ensure excellence in the construction phase. Companies should develop highly efficient systems in manufacturing by adopting lean-process planning and working to eliminate defects. Their efforts should include breaking the construction plan into discrete pieces so that each can be designed to ensure speed and minimize bottlenecks.

- Set up a project management office. A dedicated project management office (PMO) can act as the central hub for a complex project, overseeing everything from human resources needs to troubleshooting. A well-functioning PMO can go a long way toward preventing delays and cost overruns.

1. See Eight Key Levers for Effective Large-Capex-Project Management: Introducing the BCG LPM Octagon, BCG Focus, October 2012.

Manage Operations and Financial Risks

Once operational, a PPP must be run with the same rigor and discipline used to run any large business. This can entail hedging commodities exposure, for example, or creating a forward-looking strategic workforce plan.

Consider the workforce challenges that utilities in developed economies face. Because of a demographic shift in these countries, many utilities are facing a dearth of engineers and other skilled labor in the future, which could hamper the operation and the maintenance of their power plants. As a result, several utilities have modeled in detail their exposure to demographic risks by breaking down their labor force into different skill categories and forecasting both the need and the anticipated supply of laborers in those categories. That analysis then becomes the basis for developing concrete measures, such as establishing new recruiting channels, that are designed to prevent skilled-labor shortages in the first place.

Private-sector companies must also manage the risk posed by adverse regulatory decisions. Certainly many of those decisions are not within the control of private companies. But it is crucial to have ongoing, productive relationships with regulators to deal with technical, legal, and other issues as they arise. Most companies that are experienced in PPPs, therefore, have established senior regulatory-affairs departments that handle all regulatory negotiations, understand regulatory regimes and best practices in different locations, and coordinate much of the communication with regulators.

Managing financial risks is also key. Most infrastructure assets require long-term financing, which is not always available at the right rates. Therefore, concessionaires need to actively manage and optimize their financial structures over the life cycles of their projects. This is particularly true for greenfield projects, where the project risk changes dramatically over time as construction risk is eliminated and actual demand is unveiled. This changing risk profile may require using different forms of financing over time to effectively mitigate refinancing risk and take advantage of lower credit spreads. For example, a project may initially be funded with bank debt and a private equity coinvestment but then switch to long-term bonds or a pension fund coinvestment for the remainder of the concession. Refinancing risks (and upsides) should ideally be shared with the public sector through the contract or regulation design.

Shape Public Perception

Infrastructure PPPs are more vulnerable to public backlash than any other type of business partnership. In fact, negative public opinion can completely derail an otherwise strong project. The reason: the risk of politicians intervening in a way that hurts the private sector rises exponentially when public perception of the project turns negative. This is especially true when the public begins to question whether profit motives will undermine safety or other public interests.

A key tool for ensuring against such a backlash is to build trust by engaging in community dialogue about the project early on. For example, the concessionaire in a PPP for water in Southeast Asia promoted public understanding and water conservation education by offering tours for schools and selling water to poor residents at reduced tariffs. Companies in other projects have used Internet communications, community information sessions, and public displays of project details. The specific approach that a company takes is less important than initiating a true two-way communication with the public to begin with. When people are invited to help shape a project’s design and talk about any negative impacts, they are more likely to look favorably upon the endeavor. Celebrating key milestones with the community can strengthen public support as well.

Transparency, too, helps to build trust with the public. Companies should have a clear plan for addressing, monitoring, and reporting on key public concerns, such as environmental degradation or affordability issues for the poor. In some cases, companies may need to exceed the quality levels called for by the contract to convince the public that negative effects from the project are being minimized.