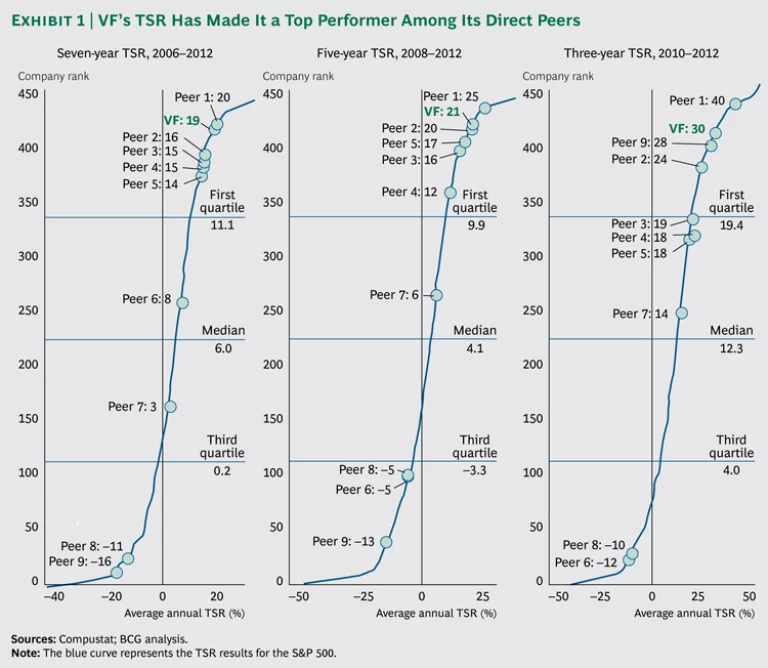

VF Corporation is the world’s largest apparel company, with a market cap of $22.8 billion and a stable of strong brands ranging from heritage businesses Lee and Wrangler jeans to more recently acquired lifestyle brands such as The North Face and Timberland. Over the past seven, five, and three years, VF has delivered a TSR of 19 percent, 21 percent, and 30 percent, respectively, making it a consistent top performer among its direct peers. (See Exhibit 1.) The company just missed making our top-ten rankings for the broader global consumer durables and apparel industry by half a percentage point; it came in at number 11.

VF’s outstanding TSR performance is the product of an end-to-end transformation of the business that included a shift in primary focus from cost cutting to growth, a major reshaping of the corporate portfolio, an enhanced capital and financial strategy, and the consistent use of TSR as a lens to help focus the company’s culture and decision making on delivering strong value to shareholders over the medium to long term. “We are very proud of our track record,” says Bob Shearer, the company’s CFO since 1998 and one of the executives who spearheaded the transformation effort. “We have provided investors with ‘reason to believe.’”

Creating a New Growth Strategy

At the turn of the new century, VF was a good company with strong management but with limited organic growth. It had two large businesses: the jeanswear business, which included Lee and Wrangler (two of the three iconic American jeans brands), and the intimate-apparel business, consisting of Vanity Fair (the origin of the company’s name) and many other smaller brands. These businesses, which were responsible for about 80 percent of total revenues, generated a lot of cash flow, but they were mature, low-gross-margin segments that were growing relatively slowly. To the degree that the company was growing earnings in these businesses, it was largely through cost cutting and extremely efficient manufacturing.

At that time, the company added a few smaller lifestyle brands to its portfolio. The company acquired The North Face (then a $250 million business) in 2000 and Nautica in 2003. These brands were growing faster and had higher gross margins, but they were too small then to have much of an impact on the company’s overall top line and earnings trajectory. According to Shearer, by 2004, there was a growing conviction among VF’s senior-management team that “we need to grow this business.”

“We had a business model problem more than anything else,” explains Eric Wiseman, who became VF’s CEO in January 2008 and had previously served as the company’s president. “We had no meaningful organic growth and it was difficult to grow our gross margins. And while we had been improving our operating margin, that had come mainly through cost cutting. We were stuck at about $5 billion in revenue. We kept asking ourselves: How do we build a stronger and more compelling business model?”

Based on what they were learning from managing the new lifestyle brands, the senior team, led by then-CEO Mackey McDonald, developed a growth strategy that focused on shifting VF’s portfolio mix away from the category-driven heritage businesses toward the lifestyle brands and emphasized international growth in markets in which the company had a limited footprint. As part of the new growth strategy, the company began buying a number of youth-oriented lifestyle brands—acquiring Vans (a California-based maker of athletic shoes often used by skateboarders) in 2004 and surfwear maker Reef in 2005.

Convincing the Equity Markets

By 2006, the new growth strategy was beginning to pay off. The company’s ability to generate top-line organic growth was improving. And yet, it was as if the equity markets were discounting the improved trajectory. VF’s P/E multiple remained the lowest in its peer group. “It was very frustrating to us,” remembers Shearer. “We were growing our top and bottom line, but we weren’t seeing any improvement in our P/E. The market wasn’t giving us any credit for the new strategy and our stronger performance.”

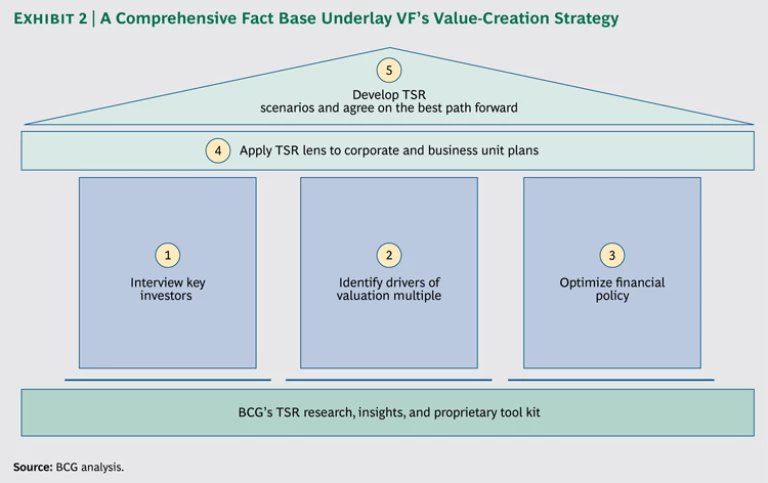

The company engaged BCG to better understand this seeming contradiction. Was VF’s management team missing something? Or was it the market? A BCG team interviewed the company’s largest investors to understand their views of VF and their investment thesis for the company. The BCG team also analyzed the drivers of differences in valuation multiples in VF’s peer group (to see what distinguished the performance of its higher-multiple peers), evaluated the company’s financial policies, and developed a number of integrated corporate-strategy scenarios in order to improve the company’s value-creation strategy. (See Exhibit 2.)

The investor interviews were sobering. In general, the investors thought VF was a good, well-managed company. But its reputation was for cost discipline and manufacturing efficiency, not growth. Investors were skeptical of the new growth strategy and worried that it was too risky. “They didn’t really see us as a growth company,” says Shearer, “so they weren’t giving us credit for our acquisitions and additional growth in those early days.” A segmentation of the company’s investor base revealed a key reason for this skeptical reaction: the dominant group of VF investors was made up of defensive value investors for whom rapid growth was simply not a high priority. They saw the company’s future and value creation path very differently than the way that its management did.

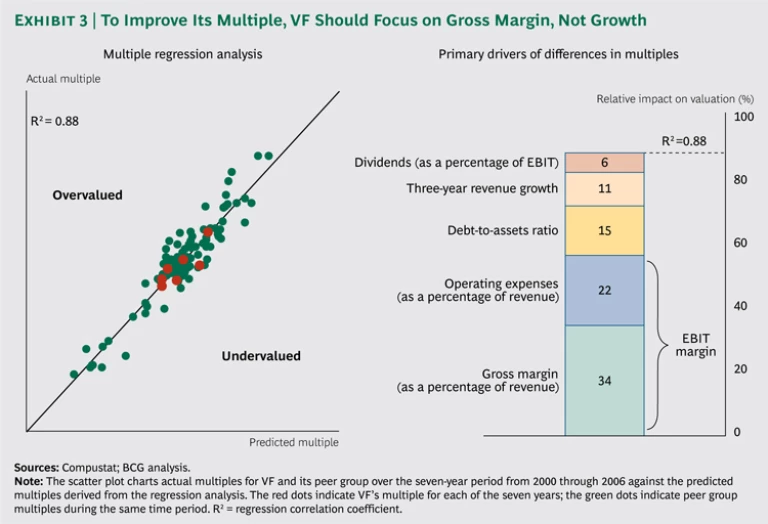

Another set of important insights came from the analysis of valuation multiples in VF’s peer group. The BCG team used statistical regression analysis to identify correlations between the range of P/E ratios in VF’s peer group and a comprehensive set of financial and operational variables, and it developed a statistical model that explained what drove the differences in valuation multiples in the apparel industry. Exhibit 3 shows the results of this analysis for VF and its peer group in the period from 2000 through 2006.

The scatter plot on the left-hand side of Exhibit 3 shows that the BCG model—based on statistical regressions of financial data from VF and its peer-group companies—predicted valuations that were a close fit with the actual valuations in the group, with an R2 (or regression correlation coefficient) of 0.88 (that is, 88 percent of the differences in valuation multiples in the group are explained by the model). The bar graph on the right-hand side of the exhibit shows that the most influential driver of differences in multiples in this group was a company’s gross margin as a percentage of revenue (responsible for 34 percent of the difference in multiples), followed by operating expenses as a percentage of revenue (responsible for an additional 22 percent).

In other words, within VF’s peer group, all other things being equal, the higher a company’s gross margins and the lower its operating expenses as a percentage of revenue, the higher its valuation multiple compared with the multiples of its peers. Together, these two factors make up a company’s EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) margin. Financial factors, such as a company’s capital structure and dividend policy, were responsible for an additional 21 percent. Meanwhile, three-year revenue growth, although obviously an important contributor to overall TSR, was, in fact, not so important in determining differences in multiples—responsible for only 11 percent of the differences in the peer group.

BCG’s multiple analysis was an eye opener for the VF senior team. “We thought that growing the top line was the key to raising our P/E,” says Shearer. “But it turned out to be far less important than we had thought. The analysis showed us that the key factor was our gross margin.” Although VF’s organic growth was improving overall, its high-margin lifestyle brands were just too small to have a material effect on the company’s average gross margin as a whole.

Improving the Multiple

The combination of the priorities of its dominant investor group, concerns about the risks associated with VF’s new growth strategy, and VF’s low gross margins helped explain why VF’s valuation multiple was the lowest in its peer group. The question was: What can we do about it?

The company developed a sequence of moves designed to deliver strong and sustainable TSR and to strengthen its multiple in the near term. The first move was a major shift in investor messaging: at an investor day in December 2005, VF executives announced an explicit top-quartile TSR goal in order to communicate to the investor community that the company was deeply committed to delivering strong and sustainable TSR, not just earnings growth, over the long term.

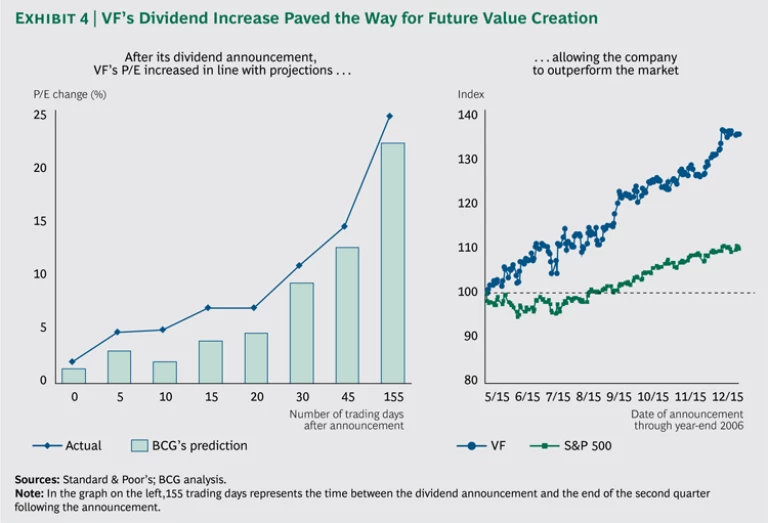

The investor day laid the groundwork for the second move. As part of BCG’s work, the team had done an event study showing that, on average, dividend increases had a much stronger positive impact on a company’s P/E multiple than share buybacks did. So on May 15, 2006, VF announced a near doubling of its dividend payout—from 23 percent of earnings to 45 percent. The increase took the company’s dividend yield from about 2 percent to nearly 4 percent. Investors found this higher yield attractive and began buying the stock and bidding up its price. Over the next six months, VF’s share price and P/E multiple increased by nearly 30 percent relative to the market, taking the company’s valuation multiple from the bottom to roughly the middle of its peer group. (See Exhibit 4.)

The dividend increase also helped protect VF’s stock price during the 2008 financial crisis. Like that of most companies, VF’s stock price fell precipitously during the crisis. However, the drop in price pushed VF’s dividend yield to about 6 percent—which had the effect of putting a floor under the stock, so the impact was not as bad as it might have been. Shearer tells the story of one investor who called him to say that he had considered selling but had concluded, “How can I sell this stock with the 6 percent yield that I’m getting?” “We fared better than most,” says Shearer, “and we feel that the dividend had a lot to do with that.”

The third move was a big one: the 2007 divestiture of Vanity Fair, one of the company’s legacy brands, as well as its entire intimate-apparel business. “It was a tough decision to sell Vanity Fair,” says Wiseman. “That’s where our company was founded in 1899 and where our name came from.” But, adds Shearer, “we just knew that from a TSR perspective, it didn’t make sense to continue to own that business.” Although selling the intimates business meant a decline in the company’s absolute earnings, it had the positive impact of a major improvement in VF’s gross margins.

Transforming the Portfolio

Even as VF was taking steps to improve its valuation multiple, it also began a series of moves to fundamentally transform its portfolio—making it more attractive to more growth-oriented investors.

To emphasize to investors the potential of its new focus on lifestyle brands, the company hired a senior M&A executive from General Electric to run its acquisitions process. It also provided investors with greater clarity about its M&A strategy and track record. Both moves helped build VF’s credibility as an acquirer with growth investors. The company also began reporting earnings separately for its lifestyle brands in order to emphasize their higher margins and growth potential. Finally, it hired a new corporate-strategy executive and announced the creation of an internal talent-management program that would build the capabilities necessary to manage a stable of high-growth lifestyle brands.

When he became CEO, Wiseman focused on three major growth initiatives: expanding the company internationally, increasing its direct-to-consumer business, and investing in innovation in order to develop more compelling products and more effective marketing. “I focused on these three areas because each of them provided us with ways not only to grow faster but also to expand our gross margins,” says Wiseman.

“But one of the smartest things we did,” he adds, “was to explain to our people why delivering strong TSR over the medium to long term mattered and the key drivers that would allow us to make that happen.” This initiative took the form of institutionalizing a TSR perspective in the management ranks. More than 200 managers across key businesses and regions have been trained in the principles of TSR and how the TSR lens can be used to improve decision making. Today, the company assesses every proposed financial plan and the performance of every brand and business in terms of its TSR contribution. “People now understand that we need to be making decisions that enable their business, brand, and geography to contribute positively to TSR” says Shearer. “It helps people understand why we are making the decisions that we make.”

The key drivers of TSR are also built into the company’s management-incentive-compensation plan. For example, it used to be that the annual bonus was based exclusively on earnings growth. Today, it includes criteria for gross margins, the generation of free cash flow, and revenue growth. “We pay people to deliver what fuels our TSR,” says Wiseman. And what gets measured gets done. “In the year that we started rewarding our people for the generation of free cash flow,” says Shearer, “our total free cash flow grew almost 50 percent—from $650 million per year to $950 million.”

According to Wiseman, embedding the TSR perspective in the VF culture was a foundational element in the company’s success. “What helped us most,” says Wiseman, “is that we got a clear understanding of the TSR levers available to us. It allowed us to distort our time and resources to what really mattered. Instead of spreading our capital and managerial attention ‘democratically,’ we focused on those brands that would really drive our TSR performance.”

These moves had the impact of improving the company’s overall growth profile, attracting more growth-at-reasonable-price investors, and generating more cash to fund both organic and acquisitive growth. They also fundamentally changed investors’ image of VF. One sign of that change: in 2011, VF acquired outdoor-footwear company Timberland for $2.3 billion, the largest acquisition in VF’s 112-year history. The company paid a significant premium, causing Timberland’s stock to rise after the announcement of the deal. And yet, investors were so confident in VF’s ability to create value from the deal that its own stock price rose (by 10 percent) after the announcement, creating an additional billion dollars in market capitalization.

“Getting to $200 per Share”

In 2006, at the beginning of VF’s new value-creation strategy, the company’s stock was selling at around $60 per share. At the time, Shearer did a presentation for VF management titled “Getting to $200 per Share.” “People thought I was crazy,” he remembers. “But today, we’re hovering right around $200, and people feel great. They say, ‘We are doing what we said we were going to do.’”

Today, VF’s transformation is complete. The company has five brands with more than $1 billion in revenues that together represent about 70 percent of total revenue. The North Face should hit $2 billion in 2013, and Vans, which was a $340 million business when VF acquired it in 2004, should hit $1.7 billion. In five years, VF’s lifestyle brands should deliver a full two-thirds of VF’s total revenue—a dramatic shift from where VF was in 2005, when those brands contributed less than 30 percent of the company’s total revenue.

According to CEO Wiseman, the new VF business model still has enormous TSR potential. In June 2013, VF unveiled a new five-year plan to investors. (Its previous five-year plan was introduced only two years earlier, but the company has already achieved about 70 percent of that plan’s financial goals.) By 2017, the company plans to grow its international business from $4 billion to $7.5 billion and nearly double its direct-to-consumer business from $2.3 billion to $4.4 billion. “We have barely scratched the surface,” says Wiseman. “The potential is nearly limitless.”