The automotive industry has been operating in a business environment destabilized by a global financial crisis, local credit contractions, and pervasive political uncertainty. To serve a demanding global marketplace that’s in constant flux, some industry players will have to undertake a broad restructuring of their value propositions, product portfolios, finances, and governance. The following case studies highlight how three companies—two original-equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and a component maker—have created above-average value by taking strategic steps, such as upgrading their business models, improving asset productivity, reducing complexity, and cutting costs.

Bajaj Auto Grows Up Fast

Bajaj Auto was unquestionably a company in the right place at the right time, poised to prosper on the strength of India’s growing middle-class wealth and motorization. But Bajaj was not content to rely on demographics alone for its growth. Its success should serve notice to the rest of the industry that emerging-market OEMs are rapidly developing the scale and savvy to take on all comers.

In recent years, Bajaj reinvested heavily in its flagship Discover brand and launched two new models, the 100M and the 125, that carry the Bajaj nameplate. The company undertook a top-to-bottom revamp of its three-wheel product line, as such vehicles are a key segment of India’s urban and rural vehicle markets alike. When completed, the renovated portfolio will take its place alongside the 25 or so other product launches and refreshes the company has undertaken since 2007.

Bajaj’s products also sold well outside India: approximately 35 percent of the company’s output was destined for export markets, one of the highest percentages among emerging-market automakers. Exports both diversified the company’s revenue stream and provided a cushion against continued turmoil in its home market. Today, Bajaj is the best-selling brand in Africa and enjoys a sizable presence in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East as well. The new RE60 quadricycle, designed as an affordable, safer alternative to two- and three-wheel vehicles for urban transportation, should further diversify the company’s revenue stream.

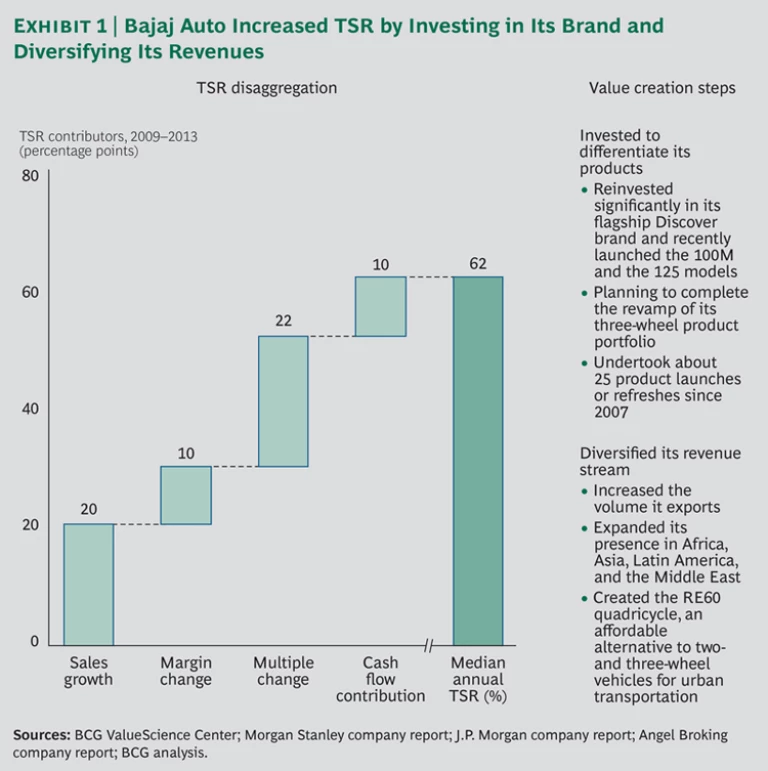

The success of Bajaj’s approach is visible in the makeup of its median annual TSR, which at 62 percent was among the highest in the industry from 2009 through 2013. (See Exhibit 1.) Sales growth contributed 20 percentage points to that total, and improved margins accounted for an additional 10 percentage points. Perhaps most remarkably, a higher multiple added 22 percentage points to TSR, a considerable feat for any emerging-market OEM—especially for a company based in India, whose equity markets are mired in a long-running decline.

Kia Scores Two Hat Tricks

A top value creator that earns most of its sales from developed markets is South Korea’s Kia Motors, which from 2009 through 2013 produced a median annual TSR of 55 percent. One hundred Korean won invested in Kia at the beginning of 2009 would have been worth 583.5 won at the end of 2013.

That’s quite a performance, considering Kia’s humble beginnings. Founded in 1944, Kia initially produced bicycle tubing and components before diversifying into trucks and, with the introduction of the midsize Brisa in 1974, passenger cars. Aided initially by a partnership with Ford, Kia grew steadily and began selling cars under its own name in the U.S. in 1994. A currency crisis in Asia forced Kia into bankruptcy protection in 1997, and in 1998, Hyundai bought the majority of Kia’s shares, forming Hyundai Motor Group.

Using BCG’s value patterns, which were introduced in our 2012 Value Creators report, Improving the Odds: Strategies for Superior Value Creation, Kia, in 2009, fit the definition of a deep-value company. Deep-value companies typically have low gross margins (a median of 18 percent, which is approximately half of the global sample median), reflecting an undifferentiated value proposition and a lack of any clear source of competitive advantage. As a result of the weak competitive positions and high debt ratios of deep-value companies, they typically have very low valuations: our global sample of deep-value companies trades at about 60 cents per dollar of enterprise book value.

Experience teaches that in order to create value, deep-value companies have to differentiate their offerings, improve productivity and margins, and reduce balance sheet risk. This is precisely what Kia did—a veritable hat trick.

It, first of all, invested strategically to differentiate its product offering. After identifying design as its “core future growth engine,” Kia, in 2006, hired Peter Schreyer away from Volkswagen—where his previous work had included the iconic Audi TT—to be its new head of automotive design. Schreyer overhauled Kia’s lineup, most recognizably by creating Kia’s new, tiger nose grille. The new emphasis on design earned Kia international acclaim, culminating in 2012, when Kia’s products won the Red Dot Award, the iF Design Award, and the International Design Excellence Award—the automotive-design world’s version of a hat trick. Kia’s focus on design was accompanied by consistent improvement in product quality. Ranked last in J.D. Power’s 2003 Initial Quality Study, Kia climbed to number 11 among 34 OEMs in 2013, while parent Hyundai Motor Group claimed the top spot.

Kia also improved its productivity and margins. Beginning in 2002, Kia embarked on a localization program, opening a production facility in China, followed by plants in Slovakia (2006) and the U.S. (2009). Combined with consistently high capacity utilization, the localization push increased the number of inventory turns from 1.16 in 2007 to 1.78 in 2013. A systematic platform-sharing program with parent Hyundai Motor Group helped reduce complexity and cut operating expenses from 23 percent of revenues in 2006 to 17 percent in 2013. Kia’s operating cash-flow margins (calculated by dividing cash from operations by total revenues) widened from –2 percent to 10 percent over the same period.

Finally, Kia reduced its balance-sheet risk. By reducing global inventory from approximately five months at the beginning of 2008 to less than two months at the end of 2013, Kia was able to reduce its total debt by about $6.5 billion and eliminate net debt.

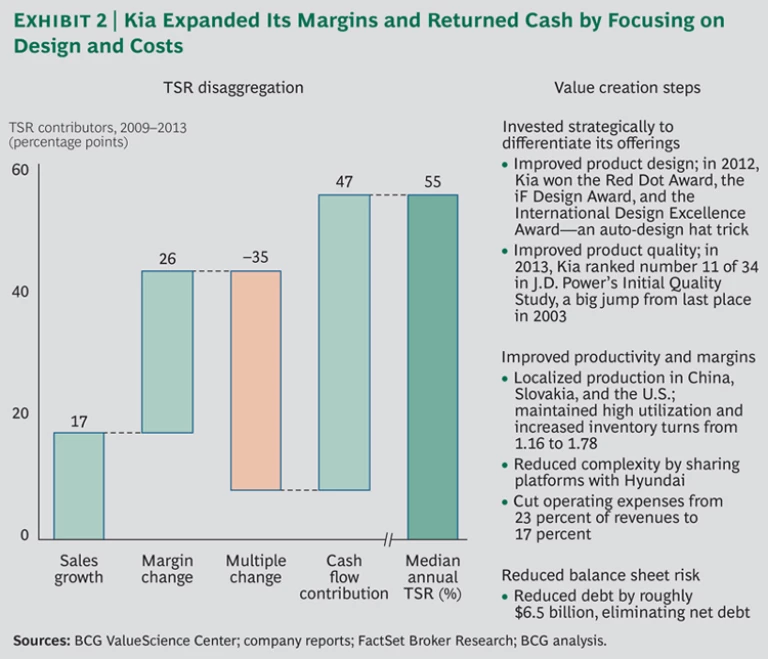

As a result of this deep-value turnaround, Kia managed to return to a balanced TSR profile. (See Exhibit 2.) Sales growth accounted for 17 percentage points of Kia’s 55 percent median annual TSR from 2009 through 2013, and margin growth contributed an additional 26 percentage points. Those elements helped offset a shrinking multiple, which took 35 percentage points off TSR. Cash flow distributions accounted for the remaining 15 percentage points.

Doorman Products: Average No More

Dorman Products, founded in 1918 in Cincinnati, Ohio, has been in the automotive aftermarket business almost as long as automobiles have been manufactured. Providing aftermarket and repair parts for vehicles in the U.S., Dorman designs, packages, contract manufactures, and markets more than 150,000 products for the light-passenger-vehicle aftermarket. In 1995, R&B acquired Dorman; in 2006, R&B changed its name to Dorman Products to take advantage of the well-established Dorman brand.

Dorman Products produced standout returns for shareholders over the short and long terms, as evidenced by its top-ten appearances in our three-, five-, and ten-year automotive-component value-creator rankings. Dorman’s consistent record of value creation derived in part from its position as a supplier of replacement parts. The aftermarket business tends to have less margin pressure than the OEM-focused supply business, and Dorman’s particular niche contracted much less than the automotive industry as a whole during the financial crisis.

Being in the right place at the right time was only part of the story, though. Dorman enjoyed very healthy cash gross margins of 34 to 40 percent. Its return on gross investment never dropped below 8 percent during the financial crisis and then held steady at 18 percent. And the company had little or no debt.

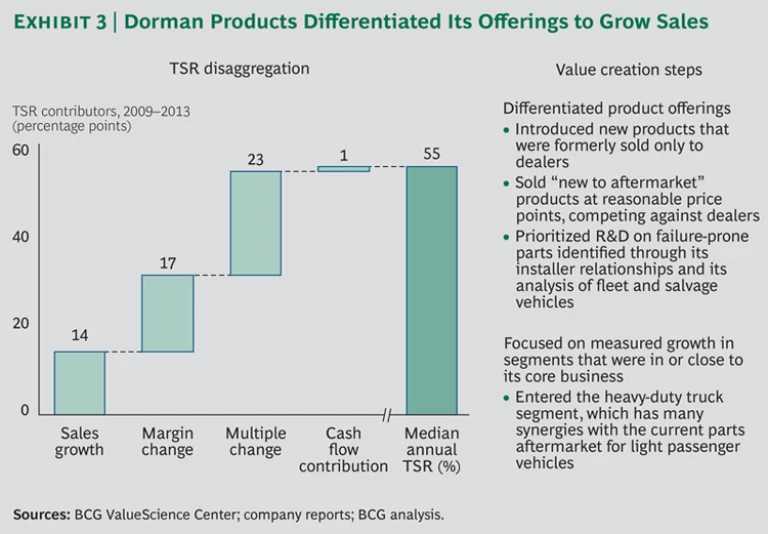

In addition, Dorman adroitly applied a few major levers to create significant value during the five years from 2009 through 2013. Using BCG’s value patterns, Dorman would have been classified as an average company in 2007. (See The 2013 Value Creators Report: Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation, BCG report, September 2013.) Dorman’s priorities helped unlock value. (See Exhibit 3.)

First, Dorman continued to develop a differentiated value proposition and thus improved or maintained its high gross margins. Second, it managed the health of its product portfolio, focusing on measured growth through careful expansion into segments that were in or had many synergies with its core business. At the same time, it largely avoided segments that added high commercial risk or complexity. To a lesser extent, it also applied other value-creation levers suitable for an average company, including de-averaging the company profile, applying differentiated strategies to diversified business units, consistently returning cash to shareholders, and protecting its customer base and market share while continually improving returns.

Dorman continued to focus on products that were new to the aftermarket, often introducing 2,000 or more products each year. Of those products introduced, typically 30 percent or more were items that were available in the aftermarket channel for the first time, being previously reserved for dealers only. During the five-year period under review, Dorman increased its parts portfolio by 45 percent while culling low-volume and low-margin products. New products were important to Dorman’s growth, with more than 20 percent of sales coming from products introduced from 2012 through 2013. This is a good example of how increased complexity can be a source of value creation, provided the complexity is well managed.

Dorman also focused on selling “new to aftermarket” products at reasonable price points, which was a strong selling point with consumers unwilling to pay dealership prices for replacement parts. The company would be able to extend its very strong growth trajectory in the U.S. light-passenger-vehicle market only as long as it could continually introduce products at advantageous price points.

To that end, Dorman used a variety of methods to target failure-prone original equipment (OE) for which it could sell a new-to-aftermarket replacement. Many new-product concepts emerged from insights gained through its strong ties with installers. By gathering intelligence from shops that had daily experience with failing OE parts, Dorman could gauge consumers’ needs and set product development priorities. To that same end, Dorman also dispatched engineers to examine fleet and salvage vehicles to identify additional failure-prone items. By focusing on products with high failure rates and sourcing roughly 80 percent of production from low-cost countries, Dorman was able to maintain a differentiated brand with attractive gross margins.