A Comeback in the Making is the first in a series of annual reports from The Boston Consulting Group on value creation in the automotive industry. The report analyzes the industry’s two largest sectors, original-equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and makers of automotive components that are sold either to OEMs or to end users in the aftermarket.

Related Article

How Three Standout Performers Raised Their Games

Three companies’ successes show the steps that others should consider as the auto industry recovers.

These two businesses are very different, with distinct dynamics, financial characteristics, typical growth rates, capital requirements, and profit margins. Nevertheless, the sectors are inextricably linked and often have in common the same challenges; a pressing one for both sectors has been finding their footing in a global economy that was rocked to its foundation in 2008. Our analysis of total shareholder return (TSR) over the past three, five, and ten years suggests that the long-awaited recovery for both OEMs and component makers is finally starting to gain traction—across countries and regions and in all subsectors.

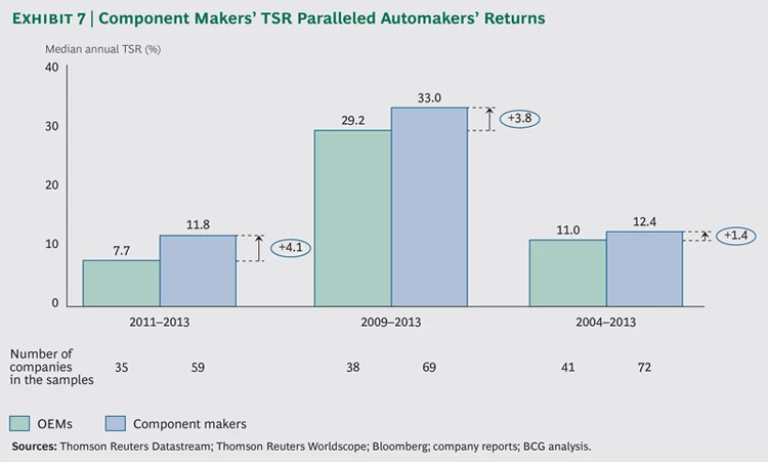

In fact, few economic sectors have mounted a more impressive comeback from the ravages of the financial crisis than those in the automotive industry. Both OEMs and component makers delivered five-year median annual returns that were well in excess of the median return for the 26 industries tracked by BCG. OEMs produced a median annual TSR of 29 percent from 2009 through 2013, while component makers posted a median annual TSR of 33 percent. The median annual return for all industries was 21 percent. The automotive industry’s recent performance represents a striking recovery from the depths of the 2008 financial crisis, when the big three U.S. automakers alone posted nearly $75 billion in losses and unit sales plunged worldwide.

However, some companies are recovering more quickly than others. Automotive OEMs recorded the third-highest standard deviation in TSR of the 26 industries BCG tracks. The top value creator, Great Wall Motor Company, posted a median annual TSR of 109 percent over the five-year period, while the worst performers destroyed 5 percent of value annually—a swing of 114 percentage points.

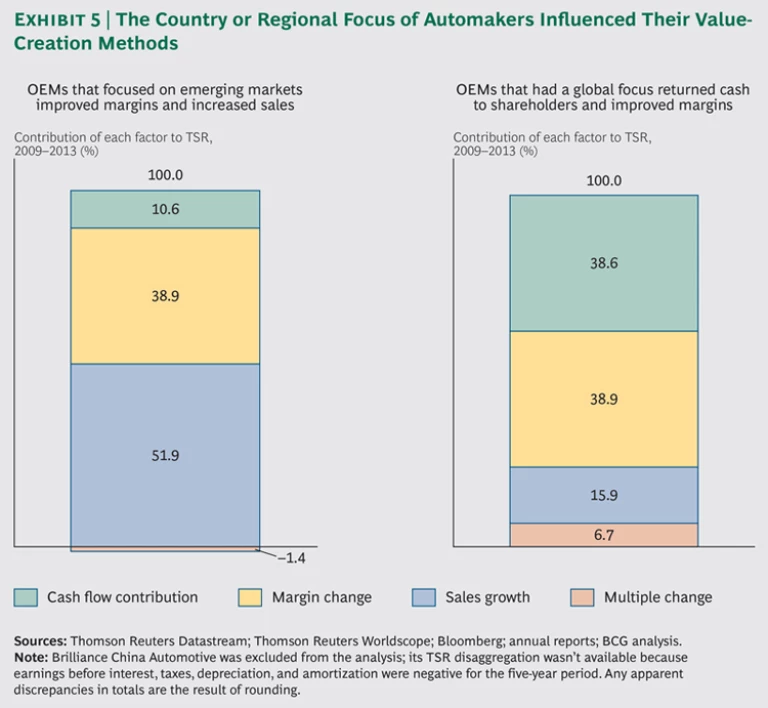

OEMs that concentrated on emerging markets produced a median annual TSR that ranged from 36 to 49 percent; automakers that focused globally on developed markets posted lower median annual returns, ranging from 23 to 35 percent. The country or regional focus of manufacturers also influenced how they created value. OEMs that concentrated on emerging markets created value primarily through a combination of margin improvement and sales growth. Almost 39 percent of their TSR was attributable to wider margins; revenue increases accounted for an additional 52 percent. OEMs that had a global focus created value in large part by expanding their profit margins and returning cash to shareholders in the form of dividends and share repurchases.

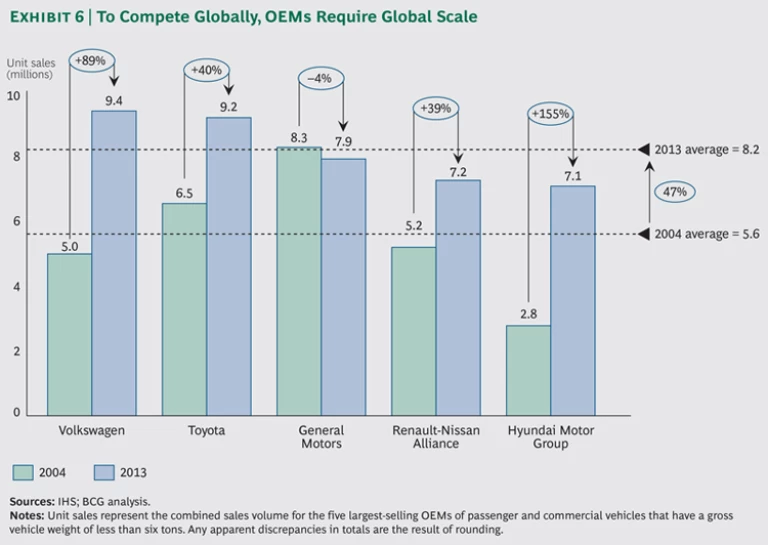

Manufacturers’ performance, highlighted by growth of 47 percent in combined unit sales for the five largest-selling OEMs during the past ten years, underscores the vital importance of global scale: it helps OEMs remain competitive on costs and positions them to capture share in high-growth markets and thus solidify their competitive advantage.

Going forward, OEMs must also make product innovation a priority, while focusing on the development of vehicles suited to the unique requirements of individual markets. Some industry players still need to undertake a broad restructuring of their value propositions, product portfolios, finances, and governance to spur the growth-propelling innovation needed to serve a global marketplace in constant flux.

The performance of component makers was to some extent dependent upon location, with those in China producing a five-year median annual TSR of 29 percent and those in the rest of the world outside the developed markets of Europe, Japan, and North America posting 49 percent. The five-year median annual TSR for European component makers was 38 percent, while their North American counterparts delivered 39 percent.

Japanese and South Korean component makers posted a median annual TSR of 29 percent in the most recent five-year period, in line with companies in China. The toll taken by the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and the weak yen was clear.

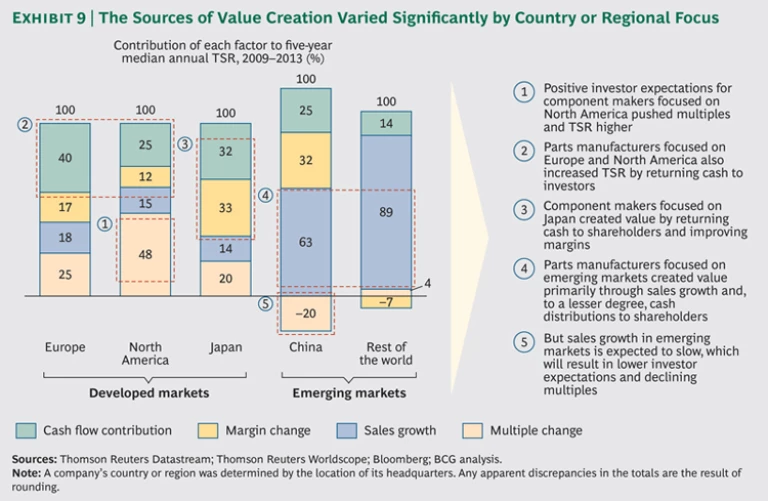

The drivers of TSR varied widely across countries and regions. Component makers that focused on the mature markets of Europe and North America generated returns largely through improved valuation multiples and cash payments to shareholders. Parts manufacturers that concentrated on Japan directed the bulk of their value-creation efforts toward returning cash to shareholders and improving margins. And component makers that focused on developing markets relied on revenue growth and, to a lesser degree, cash distributions to shareholders.

Power train suppliers were the top-performing component subsector: their revenues and returns were boosted by new laws and regulations aimed at improving fuel efficiency and reducing vehicle weight, as well as growing consumer demand for “greener” vehicles.

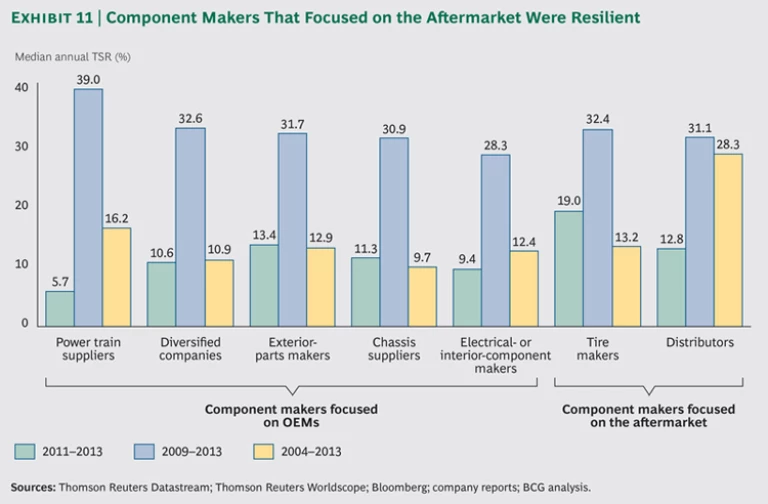

Component makers that derived a high percentage of their sales from the aftermarket channel were resilient during the most recent three-, five-, and ten-year periods. These companies benefited from approximately 14 percent growth in the number of light passenger vehicles in operation globally and about an 18 percent rise in the average age of vehicles on the road. As vehicles age, parts wear out and need to be replaced, generating a positive impact on aftermarket demand.

The growth agenda for both OEMs and component makers hinges on their ability to attain or expand global scale, establish a sustainable presence in the world’s automotive markets, and continue to support innovation.

Both OEMs and component makers should not count on a rising tide to lift all boats. These sectors have been among the biggest beneficiaries of the upswing in global capital markets from 2012 through 2013, but they shouldn’t depend on expanding market multiples to continue driving shareholder returns. The general climate may be improving, but specific moves by individual companies will determine the winners and losers in the future.

Automotive OEMs: Rattled but Resilient

We’ll say this for the automotive industry: it’s resilient. Despite operating in a business environment destabilized by a global financial crisis, local credit contractions, and pervasive political uncertainty, the industry’s original-equipment manufacturers (OEMs) turned in a median annual total shareholder return (TSR) of 29 percent for the five-year period from 2009 through 2013. (See “How We Measure Value Creation: The Components of TSR.”) It’s noteworthy that 29 percent is 8 percentage points higher than the median annual TSR of 21 percent for the 26 global industries tracked by The Boston Consulting Group. (See Turnaround: Transforming Value Creation , BCG report, July 2014.)

How We Measure Value Creation: The Components of TSR

Total shareholder return, a measure of the value a company creates for its investors, is the product of multiple factors. Readers of BCG’s Value Creators series are likely familiar with the BCG methodology for quantifying the relative contribution of the various sources of TSR. (See the exhibit below.) The methodology uses a combination of revenue (that is, sales) growth and change in margins as an indicator of a company’s improvement in fundamental value. It then uses the change in the company’s valuation multiple to determine the impact of investor expectations on TSR. Together, the improvement in fundamental value and the change in the valuation multiple determine the change in a company’s market capitalization and the capital gain (or loss) to investors. Finally, the model also tracks the distribution of free cash flow to investors and debt holders in the form of dividends, share repurchases, and repayments of debt in order to determine the contribution of free-cash-flow payouts to a company’s TSR.

These factors all interact—sometimes in unexpected ways. A company may increase its earnings per share through an acquisition but create no TSR if the new acquisition has the effect of eroding the company’s gross margins. And some forms of cash contribution (for example, dividends) have a more positive impact on a company’s valuation multiple than others (for example, share buybacks).

TSR is a useful measure of value creation, but it is determined by looking backward. As such, it is not a reliable predictor of future returns.

The industry has come a long way from the depths of the 2008 financial crisis. The U.S. was ground zero for the crisis, and accordingly, its OEMs suffered the most during the period, posting aggregate losses of nearly $75 billion and suffering declines in unit sales of as much as 55 percent (in Chrysler’s case). The damage was less severe in markets outside the U.S., but it was bad enough to doom weaker OEMs such as Saab.

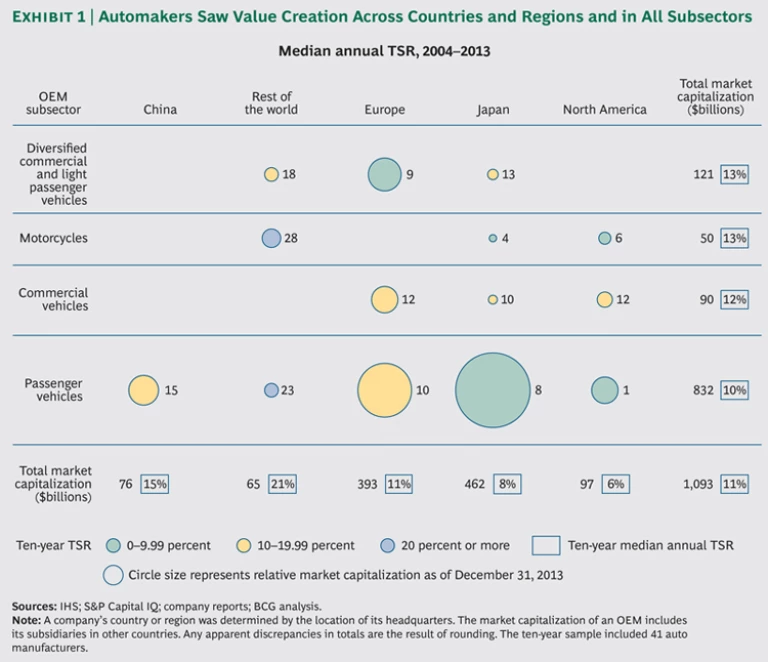

The five-year standout TSR for OEMs is not the result of a few high performers in a handful of subsectors pulling up the median. Drawn from a broad sample of 41 manufacturers, the ten-year data confirms that many OEMs across countries and regions and in all subsectors created value. (See Exhibit 1.)

A Wide Range of Returns

Although the OEM sector’s 29 percent median annual TSR outpaced most other industries, that result masks a wide range in performance by individual OEMs. In fact, automotive OEMs recorded the third-highest standard deviation in TSR of the 26 industries BCG tracks. The top value creator, Great Wall Motor Company, posted a median annual TSR of 109 percent over the five-year period, while the worst performers destroyed 5 percent of value annually—a swing of 114 percentage points.

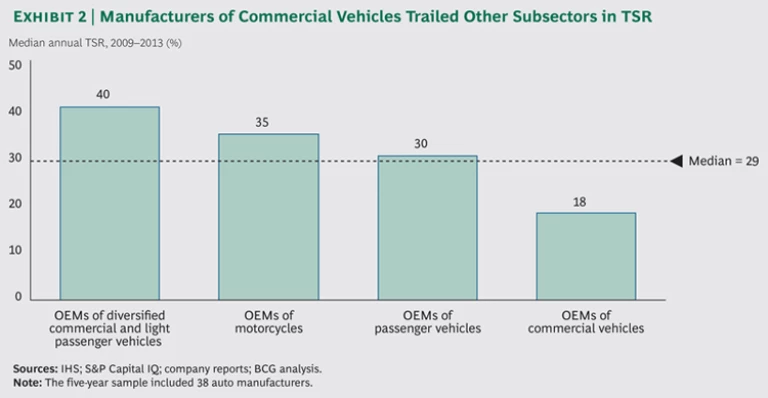

Wide performance variations also marked OEM subsectors. From 2009 through 2013, manufacturers of diversified commercial and light passenger vehicles, which accounted for 13 percent of the OEM sector’s total market capitalization, and motorcycle manufacturers, which also accounted for 13 percent, delivered a median annual TSR of 40 percent and 35 percent, respectively. OEMs in the significantly larger passenger-vehicle subsector posted a median annual TSR of 30 percent, while the commercial vehicle segment showed an 18 percent median annual TSR. (See Exhibit 2.)

Emerging-Market Sales Powered the Top Performers

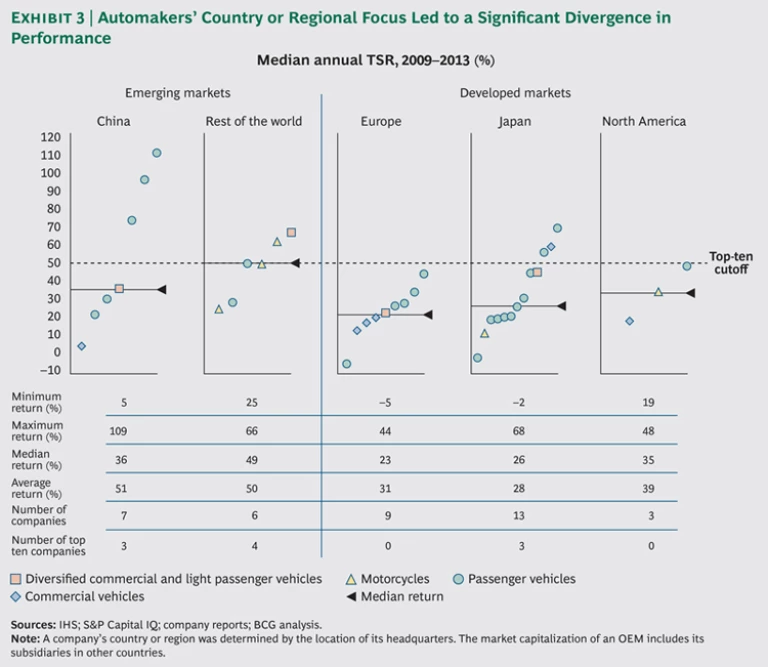

The growing wealth of the developing world powered the gains of the leading value creators. OEMs that concentrated on emerging markets produced a median annual TSR that ranged from 36 to 49 percent; automakers that focused globally on developed markets posted lower median annual returns, ranging from 23 to 35 percent. (See Exhibit 3.)

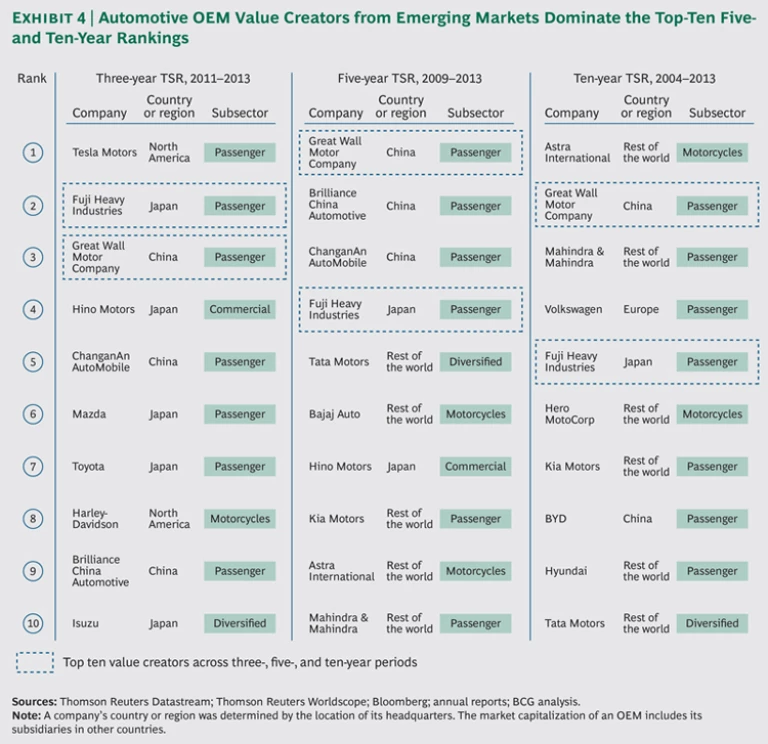

This trend is evident in the rankings of the top automotive OEM value creators. The three-year list is dominated by companies from developed markets, while the five- and ten-year rankings are dominated by automakers from emerging economies. For example, three China-based passenger carmakers, Great Wall Motor Company, Brilliance China Automotive, and ChanganAn AutoMobile, lead the list of the top ten value creators from 2009 through 2013, ahead of players such as Fuji Heavy Industries (the parent corporation of Subaru), Tata Motors, and Kia Motors. (See Exhibit 4.) It should be noted, however, that Brilliance and ChanganAn owe much of their success to their joint ventures with multinational automakers—BMW in the case of Brilliance, and Ford in the case of ChanganAn.

Country or regional focus also influenced how manufacturers created value. (See Exhibit 5.) OEMs that focused on emerging markets created value primarily through a combination of improving margins and growing sales. Almost 39 percent of their TSR was attributable to wider margins; revenue increases, a result of fast-growing personal incomes, accounted for approximately 52 percent. These OEMs returned little cash to shareholders, opting instead to add scale, expand product lines, and improve distribution and service.

The strongest five-year performers among OEMs that focused on emerging markets illustrate how these champions are rapidly developing the strategic sophistication and operational excellence that are prerequisites to competing successfully on the global playing field. India’s Bajaj Auto, for example, aggressively raised its brand profile and diversified its revenue stream to increase top-line growth and improve margins, which in turn boosted investor expectations of sustainable growth—and the company’s market multiple.

By contrast, OEMs that had a global focus, many of which initiated full-scale turnaround or restructuring programs during the period under study, created value in large part by returning cash to shareholders in the form of dividends and share repurchases and by expanding their profit margins. In many cases, these manufacturers also benefited from multiple expansions influenced by investor expectations of the industry’s continued recovery. Although Kia Motors’ market multiple shrank, it is a standout performer among OEMs that had a global focus, executing a comprehensive overhaul of its product line, operations, and financial position that elevated the company into the top ranks of automakers and spurred demand for its products.

Important Takeaways for OEMs

Several clear priorities for automotive OEMs emerged from our analysis of TSR. Automakers should add global scale and presence, innovate to capture share, consider restructuring to improve TSR, and prepare a value creation strategy.

Adding Global Scale and Presence

Manufacturers’ performance, highlighted by a growth of 47 percent in combined unit sales for the five largest-selling OEMs during the past ten years, underscores the vital importance of global scale. (See Exhibit 6.) Global scale not only helps OEMs remain competitive on costs but also positions automakers to capture share in high-growth markets and thus solidify their competitive advantage. It is no mere coincidence that from 2004 through 2013, top performers such as Volkswagen and Hyundai Motor Group roughly doubled the number of markets in which each sells at least 100,000 units. These companies had the global scale to establish a pervasive presence in new markets, which enabled Volkswagen to increase sales from 5 million units in 2004 to 9.4 million units in 2013, an 89 percent gain in volume; Hyundai Motor Group posted a rise in sales from 2.8 million units in 2004 to 7.1 million units in 2013, a stellar 155 percent increase.

Global scale in itself is not sufficient to boost TSR, however, especially if growth comes at the expense of profitability. For the past five years, emerging-market OEMs Hero MotoCorp and BYD turned in annual sales-growth rates that ranged from 15 to 20 percent, but their margins barely budged, growing no more than 2 percent annually. Global scale can help OEMs attain and maintain a high TSR, but not without margin expansion.

Innovating to Capture Share

OEMs must also make product innovation a priority, while focusing on developing vehicles suited to the unique requirements of individual markets. To successfully serve an emerging market, for example, an OEM might need to develop a low-cost, easy-to-operate, ultrasmall vehicle, while at the same time developing for mature markets a family van that has multiple components connected to the Internet. As is the case in many other industries, the top TSR performers among automotive OEMs have outspent their rivals on R&D and filed more patents.

Restructuring for Improved TSR

To spur the growth-propelling innovation needed to serve a demanding global marketplace that’s in constant flux, some industry players will have to undertake a broad restructuring of their value propositions, product portfolios, finances, and governance. That will require those OEMs to reexamine and redefine their core value proposition to highlight points of differentiation and competitive advantage. The new value proposition should lead both the overhaul of the core product portfolio (and high-return adjacencies) and the divestment of noncore, low-return assets. To support the transformation to an innovative company, OEMs will need to make targeted investments to radically improve the business model, continuously improve asset productivity, reduce complexity, and cut costs.

Ford has already traveled some distance down this route, successfully refocusing its core portfolio on high-quality, affordable vehicles that are adaptable to a wide variety of markets. At the same time, it discarded or divested noncore nameplates such as Aston Martin, Mercury, and Volvo, as well as parts maker Visteon.

General Motors has also slimmed down drastically in the past several years, discontinuing its Daewoo, Hummer, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, and Saturn nameplates, selling its Saab unit, and divesting its share of New United Motor Manufacturing, a joint venture with Toyota. It has also invested heavily in alternative-fuel technology, although sales of alternative-fuel vehicles have been disappointing to date.

Hyundai Motor Group, for its part, has invested strategically to improve product quality and technology and has initiated operational improvements to increase both productivity and margins. The stronger cash flow generated by these measures has enabled the company to deleverage dramatically and halve its debt-to-enterprise-value ratio.

Fiat and Tata Motors have taken a different turnaround route, using expedient acquisitions as their launching pads. Fiat swooped in to acquire key Chrysler assets while the U.S. company was under bankruptcy court protection and then used those assets to redefine Chrysler’s value proposition. It repositioned flagship products, such as the Jeep Grand Cherokee, as premium vehicles and launched a world-class manufacturing initiative to upgrade the entire product line and sharply reduce manufacturing waste.

Tata, for its part, has capitalized on its acquisition of the Jaguar and Land Rover brands to reinvigorate its product line, releasing new models such as the XF and the Range Rover Evoque. At the same time, Tata invested aggressively but strategically to enlarge its footprint in high-growth China, where the company recently opened its hundredth dealership. Inventory turnover, which has more than doubled since the restructuring, is pushing returns higher.

As many OEMs were painfully reminded during the financial crisis, such transformations are impossible to execute from a shaky capital base. Automakers should raise capital sufficient to stave off disruptive defaults or early repayment demands and use their cash flow to deleverage. Reduced dependence on a single country or region, market segment, or product will in turn reduce risk, as will greater control over the cost of critical inputs.

Inorganic growth, though indisputably vital to some restructuring plans, needs careful management and discipline to avoid deals that make a splash without adding substantially to cash-on-cash returns. Acquisitions should focus on filling strategically important gaps and amassing the scale needed to play in the global arena. Automakers that have successfully acquired companies could very well have the advantage here, applying what they’ve learned from earlier restructurings to unlock the value latent in their target companies.

Governance should be aligned with an automaker’s restructuring strategy. Management incentives should be designed to support the major levers of TSR: margins, capital returns, and effective risk control. And as financial stability returns, OEMs should shift their focus to returning cash to shareholders steadily and predictably.

Preparing a Value Creation Strategy

Whether or not OEMs contemplate restructuring, they need to prepare a long-term value-creation strategy that takes into account all the drivers of TSR. To implement the strategy, automakers should cultivate execution excellence along multiple dimensions, including product quality, supplier relations, manufacturing footprint, and globally optimized platforms. Attaining excellence on the latter will prove especially challenging, as manufacturers will have to deliver high-performance, regulation-compliant vehicles for mature markets while optimizing costs for emerging markets.

In addition to these considerations, OEMs face a number of longer-term strategic issues for which they will have to define their course to stay relevant in a fast-moving market. These issues include the following:

- The Increasing Importance of the Connected Car. The rising number of embedded electronic components and the related external infrastructure requirements (such as sensor-equipped roads) will pose significant cost challenges even as OEMs deliver a value-adding suite of services.

- Higher Standards for Emissions and Fuel Economy. Meeting the standards set to take effect in 2025 and 2030 will require OEMs and their supply chains to innovate in power trains, transmissions, and lightweight materials.

- New Retail Concepts. OEMs need to develop an end-to-end digital strategy stretching from lead generation and virtual showrooms to a full e-commerce consumer offering.

- The Rise of New Mobility Concepts. Developments such as self-driving vehicles and car sharing promise to wreak profound changes on the automotive industry, altering consumer choices and behaviors and attracting nontraditional competitors (such as Google).

Component Makers: Searching for Sustainability

As we’ve shown in the preceding pages, shareholders of automotive manufacturers have generally prospered during the past five years. Shareholders of component makers have prospered even more. Like companies in the OEM sector, those in the component maker sector created significant value from 2009 through 2013, posting a 33 percent median annual TSR. (See Exhibit 7.) That showing would place component makers among the highest performers of the 26 industries tracked by BCG.

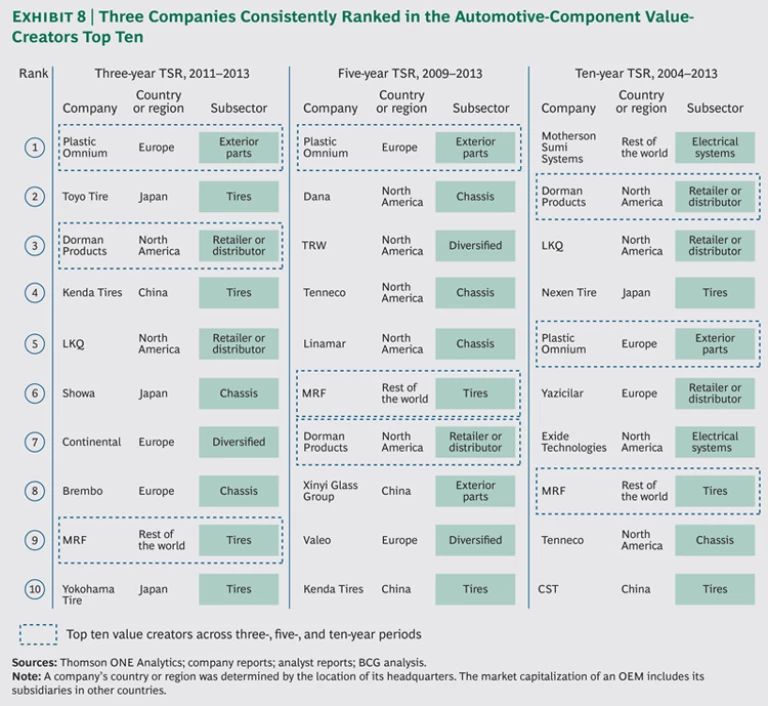

A Handful of Perennial Value Creators

The top ten performers in the component maker sector combined for a median annual TSR of 63 percent from 2009 through 2013. They were led by Plastic Omnium, with a 96 percent median annual TSR; Dana, with 94 percent; and TRW, with 83 percent. (See Exhibit 8.) Three companies—exterior-parts supplier Plastic Omnium, manufacturer and distributor Dorman Products , and tire maker MRF—ranked among the top ten performers across the most recent three-, five-, and ten-year periods. The five-year performance figures should be considered in their proper context, though. That time frame begins with the calendar year immediately following the largest contraction in global economic activity since the Great Depression; therefore, the improvement in TSR is measured from an extraordinarily low base.

Performance was to some extent dependent on location, with component makers in China producing a five-year median annual TSR of 29 percent and those in the rest of the world outside the developed markets of Europe, Japan, and North America posting a 49 percent return. The five-year median annual TSR for European component makers was 38 percent, while their North American counterparts delivered a 39 percent return.

Japanese and South Korean component makers posted a median annual TSR of 29 percent in the most recent five-year period, in line with companies in China. The toll taken by the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and the weak yen was more apparent when we looked at their returns on a weighted-average basis to reflect their market capitalizations. The disaster disrupted—if not altogether obliterated—some supply chains, and the weak currency severely slowed economic activity.

Assembly Rates Are Stuck in Neutral

Automotive assembly rates fell into negative territory in Europe and Japan in the five years following the 2008 financial crisis, but nearly €8 billion in European government-subsidized scrappage programs generated enough new-vehicle sales to hold sales declines from 2008 through 2009 to 4.9 percent in Europe. Japan’s scrappage initiative was less successful, as demonstrated by that country’s 8.3 percent drop in automobile sales during the same time period. Economic softness attributable to the Fukushima Daiichi disaster and the weak yen were again the culprits, slowing inventory turnover in the automotive industry.

Like TSR performance, the sources of TSR varied widely across countries and regions. (See Exhibit 9.) Component makers that focused on the developed markets of Europe and North America generated shareholder returns largely through improved valuation multiples—which increased in response to rising investor expectations—and cash payments to shareholders. Parts manufacturers that concentrated on Japan, the third member of the triad of primary mature markets, directed the bulk of their value-creation efforts toward returning cash to shareholders and improving margins. And component makers that focused on emerging markets relied on revenue growth and, to a lesser degree, cash distributions to shareholders to drive TSR. Sales growth has already begun to slow in China and the rest of the world, however, and with investors clearly expecting more of the same, earnings multiples have fallen, to the detriment of TSR.

Power Train Suppliers Are in Overdrive

Power train suppliers were the top-performing component subsector; their revenues and returns were boosted by new laws and regulations aimed at improving fuel efficiency and reducing vehicle weight, as well as growing consumer demand for “greener” vehicles. Suppliers’ efforts to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are centered around dramatic efficiency improvements in internal-combustion engines. By 2020, innovations in drivetrain technology promise to reduce emissions by some 40 percent, at a cost to consumers of roughly $50 to $60 per percentage point reduction in CO2 emissions, the equivalent of about $2,000 per vehicle. These fundamental factors, which got a significant boost in 2008 after several years of oil price increases, have propelled four power-train-focused suppliers from our sample into the top quartile of value creators over the most recent five-year period. (See Exhibit 10.)

The Aftermarket Advantage

Compared with component makers that sold products predominantly to OEMs, those that derived a high percentage of their sales from the aftermarket channel were more resilient during the most recent three-, five-, and ten-year periods. (See Exhibit 11.) They benefited from approximately 14 percent growth (a CAGR of 3 percent) in the number of light passenger vehicles in operation globally and about an 18 percent rise (a CAGR of 3 percent) in the average age of vehicles on the road. (See Exhibit 12.) The developing world accounts for most of the growth in both categories. In China, for example, the number of light passenger vehicles is growing at a CAGR of 16 percent, compared with 5 percent in the rest of the world, and less than 1 percent in the triad markets.

The rising age of vehicles is a positive fundamental. The average age of a light passenger vehicle in China is rising at a CAGR of 17 percent, compared with 2 percent in the triad markets. As vehicles age, parts wear out and need to be replaced, generating a favorable impact on aftermarket demand.

Imperatives for Growth

Just as the TSR of component makers closely tracked that of OEMs, so, too, does the sector’s growth agenda closely resemble that of OEMs. It hinges on the ability of component makers to attain or expand global scale—which they need to establish a sustainable presence in the world’s automotive markets—and to continue supporting innovation. Parts makers should also nurture aftermarket business.

An Agenda for Component Makers

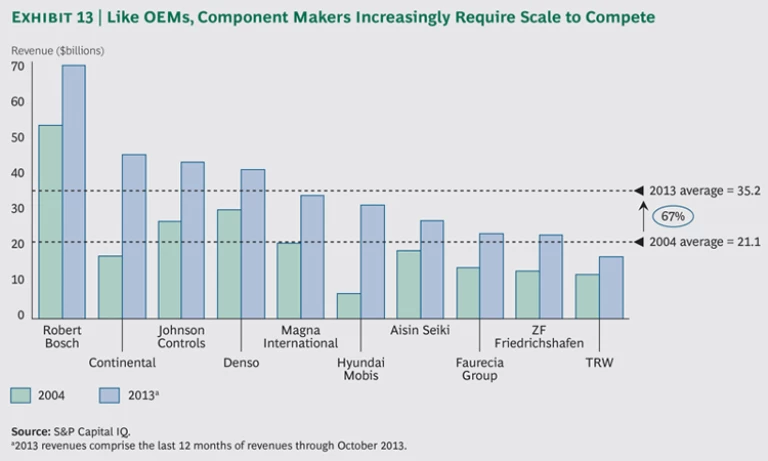

Global scale is self-reinforcing. Or to put it another way, the big tend to get bigger, as is demonstrated by the 67 percent average increase in the revenues of the top ten component makers (by size) from 2004 through 2013. (See Exhibit 13.) Global scale has enabled leading players to compete effectively on cost in disparate markets and to support the product development efforts demanded by OEMs, which increasingly rely on parts manufacturers to deliver the innovations in power train technologies and lightweight materials that differentiate their vehicles.

Component makers will also need a truly global footprint to compete effectively. A significant presence in key markets will enable these companies to serve the growing number of OEMs that have developed single global platforms to facilitate building and selling vehicles in multiple markets.

Component makers will face increasing pressure in the coming years to step up their investments in innovation—or more specifically, in the engineering prowess needed to develop products that meet the unique needs of individual markets. Winning players will be acutely alert to the voice of the customer, will identify technology and knowledge gaps quickly and accurately, and will pool their strengths with well-chosen strategic partners to develop emerging technologies. In the past ten years, component makers have surpassed OEMs in the number of patents filed; going forward, parts manufacturers must increasingly differentiate themselves by their ability to produce a continuous stream of innovations.

At the same time, component makers will need to devote significant management time and energy to nurturing aftermarket business in new markets and segments. By steadily increasing the share of aftermarket sales in their revenue mix, these companies can cushion themselves against cyclical fluctuations in the OEM channel.

Developing a Strategy for Sustainable Returns

The aim of building global scale, establishing a global presence, and innovating is to set a company on a course of sustained, above-market TSR performance. BCG tackled the question of sustainability several years ago. (See Searching for Sustainability, BCG report, October 2009.) We introduced the TSR sustainability matrix—a framework for graphically portraying the dynamic relationships among the sources of TSR. This framework enables company leaders to quickly visualize the organization’s growth drivers and plan how to optimize each of them for sustained TSR performance. The point of the exercise is to enable senior executives to develop a detailed roadmap to sustained value creation that includes the following:

- An explicit TSR target that strikes an appropriate balance first between a company’s aspirations and what it can realistically achieve and then between short- and long-term performance

- A detailed understanding of the performance improvements required in order to achieve that TSR target and the precise sequence in which those improvements need to take place

- A sense for how shifts in a company’s valuation multiple will likely impact the company’s performance requirements, as well as contingency plans for dealing with those shifts if and when they occur

- TSR-based operational targets and metrics that a company can apply throughout the organization and embed in its incentive and compensation systems

- Shifting the planning, budgeting, and capital-allocation benchmarks away from attaining annual incremental improvements to historical performance and toward a set of criteria based on contribution to long-term TSR

Analyzing a company’s performance in terms of its ability to deliver sustainable value creation is what investors do every day. Armed with the right tools, there is no reason why executives can’t develop an even better-informed perspective, given their intimate knowledge of the company’s plans and industry trends. When executives do, they can stay one step ahead of investor expectations and consistently generate superior shareholder value for many years to come.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Philippe Dehillotte, Andreas Dinger, Hady Farag, Andrew Gillespie, Kerstin Hobelsberger, Vikram Janakiraman, Nikolaus Lang, Sudarshan Mhatre, Matt Smith, and Ryan Thorp for their contributions to the research.