It is a buzzword that has been thrown around in the pharmaceutical industry for years: multichannel marketing (MCM). MCM—the use of a variety of sales and marketing channels, from face-to-face meetings to digital marketing campaigns to smartphone and tablet apps—can produce large gains in company performance. How large? Effective MCM can boost top-line growth by more than 10 percent or reduce costs by 10 to 25 percent—or both.

To deliver on that promise, companies must see MCM for what it is: a transformation of the entire marketing and sales approach . This calls for a new way of thinking. Too many people still view MCM as an add-on to traditional marketing when in fact it must be fully integrated across the organization, serving as a mechanism for coordinating all interactions with customers. In addition, many companies spend too much time with small pilots instead of moving to implement MCM on a large scale. Only when MCM is viewed clearly as the future direction, rather than as just another experiment, can companies build the required support to deploy it aggressively—and be able to “move the needle” in a meaningful way.

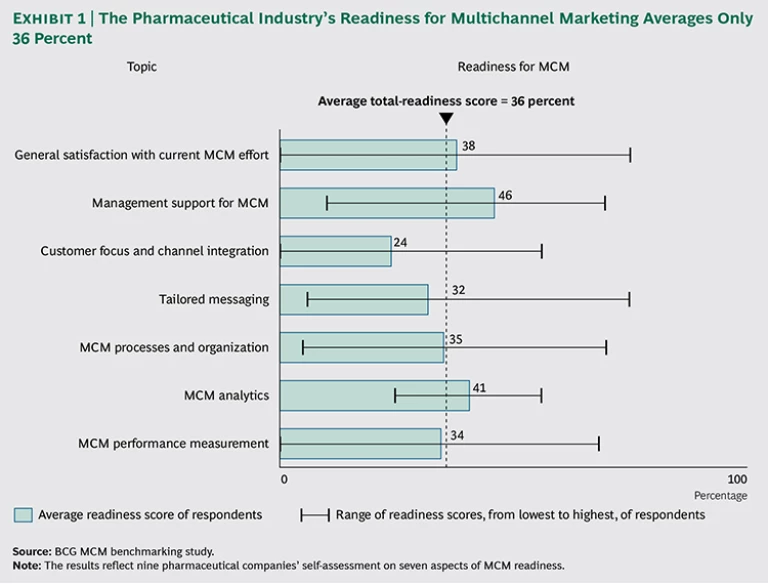

Other industries, such as retail banking and telecommunications, have demonstrated how to make this transformation. In retail banking, for example, almost 70 percent of direct customer interactions went through remote channels such as phone calls, online banking, and mobile banking by 2013, up from only 30 percent in 1999. The pharmaceutical industry lags far behind. The Boston Consulting Group’s MCM benchmarking study found that no pharmaceutical companies are strongly satisfied with their MCM efforts and that a full 55 percent are either partially or strongly dissatisfied.

It does not have to be this way. Pharmaceutical companies have all the information necessary to take advantage of MCM, especially data on physician interactions from digital marketing campaigns (e-campaigns) and from face-to-face sessions that reps have with those physicians. However, many companies lack an intelligent, comprehensive approach that pulls together all that information and uses it to execute an integrated MCM strategy, one that is fine-tuned over time on the basis of feedback regarding what works and what does not.

Smart MCM integrates information and activity throughout the entire organization. This involves three key steps:

- Deciding which models for building personal relationships make sense on the basis of the individual physician being targeted and the product being promoted

- Determining which combinations of channels and digital tools will help deliver on the goals for a particular product brand

- Harnessing big data analytics to tailor the use of channels and tools to meet the preferences and habits of individual physicians

At the same time, companies must build the infrastructure to execute MCM, including updating internal processes, upgrading IT systems, and acquiring new digital skills. Only then can MCM move from concept to reality.

Many Pilots—But Limited Success

Pharmaceutical companies first discovered MCM on a broad scale during the late 1990s. During that period, companies were enthusiastic about the power of MCM, convinced that their entire marketing effort would be digital soon after the turn of the millennium.

That optimism was short lived. The bursting of the dot-com bubble, along with some less-than-stellar results from pilots, prompted pharmaceutical companies to take a more cautious view of the Internet’s power to transform marketing. During this period, MCM stalled. But more recently, as the success of MCM in other industries became apparent and as traditional access to physicians became more difficult, pharmaceutical companies refocused on the effort and began widespread MCM experiments. Although there have been notable successes, there have also been failed efforts and a general inability to consistently scale up MCM across different locations and therapeutic areas.

The gap between MCM objectives and MCM results is evident when you look at a couple of statistics. Right now, physician participation rates in purely digital marketing campaigns—electronic continuing medical education (e-CME) programs or product websites and quizzes, for example—average only 2 to 5 percent. Also, remote communications (phone or video calls) often suffer from a lack of physician interest. For example, less than 15 percent of physicians, on average, agree to receive detailing phone calls from call centers.

Despite the bad news, there is no doubt that the health care community is ready for an integrated MCM approach. More and more, physicians embrace new technology in their professional lives: a full 66 percent of U.S. physicians use tablets in their practice and more than 90 percent of European physicians consider the Internet essential to the operation of their practice.

BCG’s benchmarking study—which involved 9 of the 25 leading global pharmaceutical companies, with combined global revenues of $265 billion—revealed how some companies are successfully harnessing MCM to transform part of their business by reaching more customers and connecting with them more deeply. In one case, a social-network campaign aimed at physicians who prescribe a primary-care brand in the UK resulted in a 15 percent jump in sales over only 12 months. In another instance, a company selling a mature brand replaced its traditional sales force with a model that combined reps in a call center and a limited sales force in the field. That slashed costs for that brand because about 50 percent of the sales force previously deployed on the brand was redirected to other products, with product revenues holding steady.

Such MCM home runs, unfortunately, remain rare. Our benchmarking study found that satisfaction with current MCM efforts is low in the industry, with not one company fully satisfied with its MCM efforts and only one in three partly satisfied. The average score for readiness for MCM in pharmaceutical companies, based on their self-assessment, was only 36 percent. See Exhibit 1.

The study found two primary reasons for these low scores. The first is a lack of integration between the different channels, such as face-to-face detailing and e-campaigns. Second, the industry continues to have a poor understanding of which channels are most effective at reaching individual physicians, a problem that stems from the inability to effectively target physicians on the basis of their actions and preferences.

Despite those hurdles, some 42 percent of all companies in the benchmarking study plan to increase their MCM budget in 2014, and none expect to reduce their MCM budget. In an era when pharmaceutical companies must often do more with less, companies appear to be committed to catching up in MCM.

Putting MCM into Practice

The poor execution to date does not mean that the enthusiasm for MCM is misplaced. Developing an MCM plan for any particular product requires making decisions in three key areas: the personal relationship with the physician, the channels to be used in promoting that product, and the way the use of those tools is customized to individual physicians.

Selecting the Model for Physician Interaction

MCM is not meant to reduce the personal connection with the physician—quite the opposite. Effective MCM allows for a more focused and richer personal relationship between the sales rep and the physician. Indeed, because MCM makes it possible to tailor contacts to individual physicians’ preferences, the interaction is truly more personal. And while the pharmaceutical industry today still largely relies on the traditional sales-rep model, there is an imperative to innovate.

We have identified two alternative models that involve some combination of face-to-face meetings, phone calls, e-mails, and other methods such as Web-based video meetings.

- The Integrated Customer Manager (ICM) Model. Although most company sales reps remain highly focused on face-to-face meetings, the ICM model uses both personal meetings and digital tools such as phone and video calls, apps, and personalized e-mails. In addition, ICMs can help steer physicians toward digital offerings, including e-CME programs, websites, and mobile apps. Tying together personal and digital marketing elements lifts the interaction with physicians to a new level. One large pharmaceutical company implemented an ICM model and increased the average duration of phone calls and personal meetings with physicians to 29 minutes—well above the industry’s average call time of about 5 minutes—and boosted customer satisfaction levels significantly in the process.

- The Call Center Plus (CCP) Model. Reps in the call center do not go into the field but still have one-on-one relationships with physicians—and a call center force is 30 to 50 percent less expensive than a traditional sales force. The initial introduction to the call center rep is typically made through either a field sales rep who is focused on another product or a designated sales assistant in the field. Under this latter approach, known as a tandem-rep model, two reps interact with physicians: the product expert in the call center, who develops the one-on-one relationship with physicians, and the assistant in the field, who also handles such tasks as the distribution of product samples. Once the connection is established, call center reps conduct phone and video meetings with physicians and guide them through the various digital offerings.

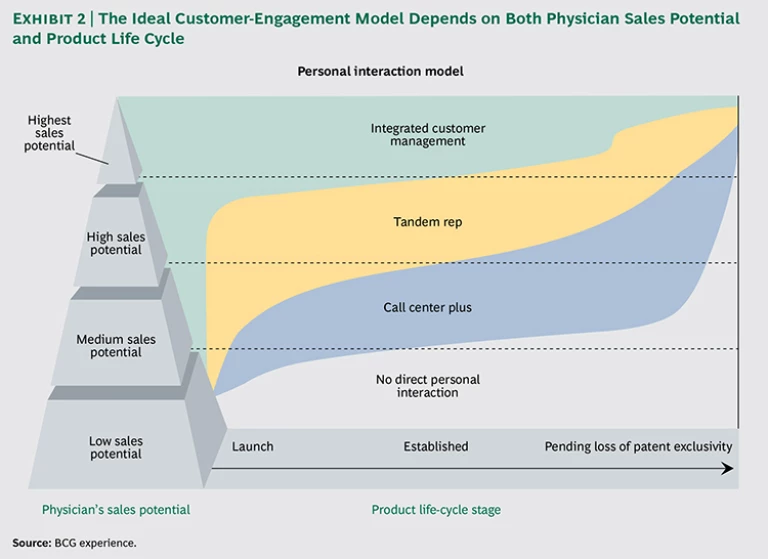

Figuring out which approach (the ICM or CCP model or a nonpersonal interaction) to use when marketing a specific product to an individual physician depends on two factors. The first is the potential prescription volume likely to flow from that physician, something that is a function of such factors as prescribing habits and the makeup of that physician’s patient group. The second factor is where the product in question is in its life cycle.

In general, the ICM model is especially effective for communicating with high-potential physicians about newer or strategically important brands, and the CCP model is a more cost-effective approach that is typically used to reach medium-potential physicians regarding products that are later in their life cycle. For physicians with low sales potential and brands that are nearing loss of market exclusivity, it might make sense to skip the personal interaction completely and use only electronic methods to communicate with a particular physician. (See Exhibit 2.)

Choosing Digital Marketing Measures

Once the decision on how the personal relationship with a physician will be managed is made, the challenge is to determine how digital channels should be integrated into that connection.

These channels fall into two basic categories. The first category is innovative new digital tools, which includes smartphone or tablet apps, simulators for training surgeons, and systems for helping physicians make diagnosis and treatment decisions. Some of these tools, such as apps that remind patients to follow their prescribed drug regimens, are scalable and have a very low marginal cost for every additional patient or physician who uses the tool. In addition, digital tools can bolster physician engagement rates and the overall value of the product—for example, by improving patient compliance with a prescribed drug regimen. In certain disease areas, where the medication mix needs to be changed or the dosage needs to be titrated, “companion apps” allow the patient to report outcomes and the clinician to titrate the drug if necessary given those outcomes. These digital tools can also help facilitate communication between physicians and patients. For example, when a patient can print a simple one-page summary from an app that tracks blood sugar, food, and exercise and then share that report with the clinician at the next visit, the conversation is changed dramatically. So instead of generic guidance from the physician about diet and exercise that the patient is likely to find unhelpful and even patronizing, the conversation can home in on the patient’s specific situation and address, for instance, the patient’s need to better manage emotional eating after a particularly stressful day at work. (See “The Power of Digital Tools.”)

The Power of Digital Tools

Digital health applications can be a powerful way to connect with physicians who have little—or no—time to see reps. But the pharmaceutical industry’s past efforts have been less than successful, with poor adoption rates for many apps. The primary reason: these initiatives were treated as one-off efforts and were too narrowly focused.

One of the most effective approaches focuses on the creation of a set of offerings that help physicians deliver care to their patients and involves patients directly in their own care, going beyond simply pushing the patient on compliance or refills. This requires a more thoughtful approach to providing functions and features that a patient would value. This may involve, for example, companies developing apps that work not only with their own products but with those of rivals. And this broader platform will likely go beyond apps. In some cases, for example, companies will develop a system for coordinating the products and services offered by an ecosystem of other partners, such as device makers and call centers.

Tying all of this together can also help close the loop with physicians by allowing the tracking of patient behavior and outcomes through sensors or self-reported data. In some disease areas, physicians welcome such information because it can guide their selection of treatment for that patient. An app that tracks the weekly diet and exercise of a patient with diabetes, for example, can help a physician zero in on specific changes in behavior or medication that might be warranted. And it could be linked to a call center where nurses could reach out to those patients who might need assistance in better managing the disease.

Such tools can make the physician more aware of the value being added by the product, insight that can affect the decision on whether to pick one brand over the other in hotly contested therapeutic areas. Designing a killer app, however, is not enough. Rather, the success of these tools depends also on marketing and sales strategies that position the app as an integral component of the drug itself and as part of the overall MCM effort.

In the future, the reach and impact of these digital measures will only grow. Some companies, for example, are studying the use of these tools as part of clinical trials. This would tie the app, website, or digital service to the product and allow the integration of that tool into future promotional efforts. The key is to design a tool that addresses the patient’s and clinician’s needs and uses prototypes and pilots to quickly test and refine the concept in the market.

The second category is e-campaigns—essentially, all marketing measures that exist to communicate with physicians outside of the traditional face-to-face interactions. These include e-CME offerings, websites, Web conferences, games, quizzes, and Facebook and other social networks such as specialized physician networks. And while these channels can be helpful in reaching physicians on their own, they are most effective when combined with personal interactions such as those encapsulated in the ICM model. The reason: companies can integrate their face-to-face communications with digital channels that are personalized for the physician in question and that are delivered by the individual rep who has the relationship with that physician.

A new question then emerges: for a particular brand, which channels should be deployed? Determining which channels make the most sense depends on the specific opportunities and challenges associated with the product in question and involves answering two questions:

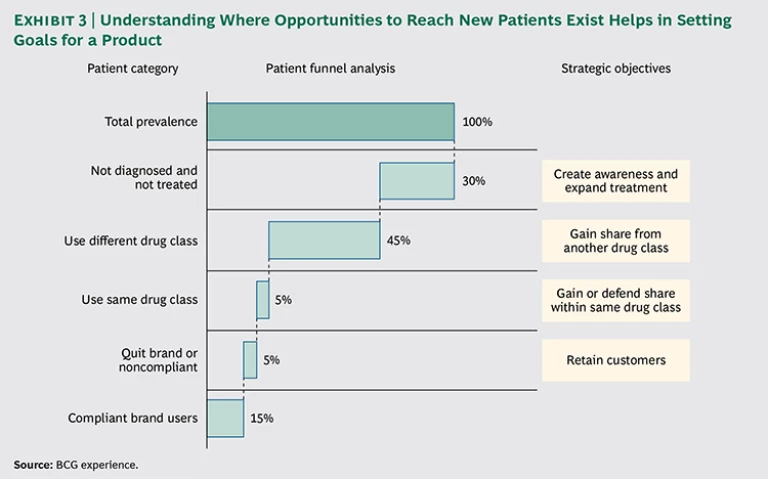

- What are the strategic goals for the brand in question? An effective way to answer this question is to use a tool known as the “patient funnel.” This is a way of studying the universe of patients suited for the drug and determining where the best opportunities lie to expand the number of patients being treated with that brand. (See Exhibit 3.) In one instance, the goal may be to simply raise awareness about a poorly understood disease; in another, it may be to grab share from rival products or to increase patient compliance with a drug regimen.

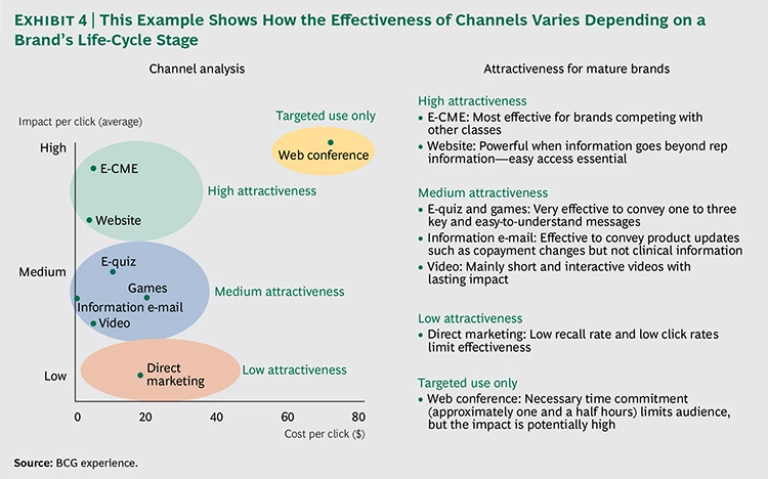

- Which digital channels are best suited to achieving those strategic objectives? Answering this question requires an understanding of the success of these channels at achieving certain goals across the industry. It is clear that certain channels are better suited to certain situations than others. For example, e-CME programs, which cannot contain material that focuses on particular brands, may be a great way to generate increased awareness about a disease but are unlikely to be effective at diverting share from similar products. The right mix of channels will also change depending on where a product is in its life cycle. For launch brands, more expensive e-campaigns, such as Web conferences, may be most effective; for mature brands, more cost-effective measures, such as e-CME programs or websites, may be appropriate. (See Exhibit 4.)

Taking a systematic approach to determining which digital-marketing measures to use can lead to a major shift in strategy. One pharmaceutical company had been focusing on battling drugs within its drug class for market share—until the patient funnel exercise revealed that the main obstacle to growth was in fact gains being made by a product in an entirely different drug class. As a result, the company invested more heavily in e-CME and Web conferences that focused on the severity of side effects associated with that other class of drugs.

Harnessing Big Data to Reach Individual Physicians

Individual physicians will respond differently to the various interaction models and marketing channels. Success lies in determining which physicians should be targeted with each and then coordinating the approach to interaction and the digital tools and channels used. Achieving this balance requires an understanding of the target audience, because failing to customize outreach to individual physicians comes at a price.

Know the risk of marketing overkill. Often, companies try to compensate for marketing deficiencies with marketing overkill, bombarding physicians with a large volume of e-mails and other digital communications that can be so overwhelming that it dissuades physicians from engaging with these marketing efforts. These missteps not only risk alienating physicians, they represent an expensive and ineffective use of resources.

Indeed, in some situations, individual physicians have received several hundred e-mails in a year from one pharmaceutical company alone. In our work with clients, we see a clear and linear relationship between the number of communications a physician receives and a decline in his or her participation rate for the programs or events offered. The lesson: don’t market in a way that makes you part of the noise and wastes an opportunity to add value during your limited time engaging a physician.

Right now, most pharmaceutical companies do not differentiate outreach to physicians on the basis of their individual digital preferences. Those companies that segment at all often do so on the basis of demographic information such as age, assuming, for example, that young physicians are more open to receiving digital communication than their older counterparts.

However, this demographic-based approach is a poor tool for predicting behavior. A study of more than 100,000 physicians revealed how poor it is. We found that all demographic groups were rather similar in terms of their usage of and attitude toward digital channels. Any correlations between factors such as age, gender, and location and the physician’s attitude toward digital communication proved too weak to serve as a basis for an effective segmentation.

Embrace effective targeting. The key is to harness big data and analytics so that outreach can be tailored on the basis of an individual physician’s history and preferences, creating “segments of one.” The analysis of past interactions with physicians, for example, can help predict the physicians’ future behavior, such as their likelihood of participating in an e-CME program, with accuracy of 90 percent or greater. But companies often are unaware of how much detailed information they have on physician preferences, are unsure of how to use that data, or lack the big data analytics expertise to effectively harness the information.

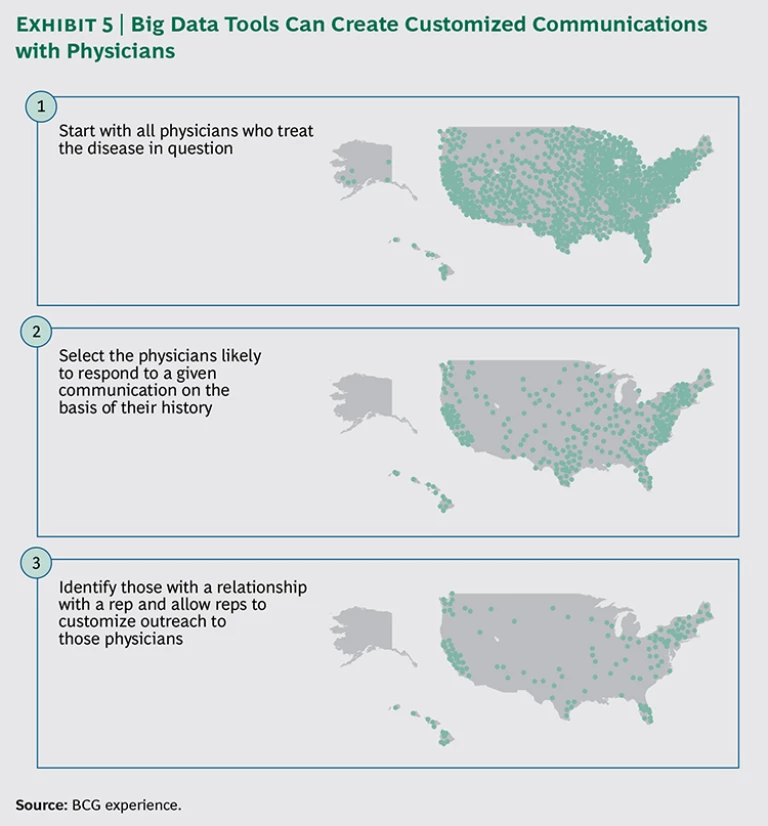

Integrating specific physician-behavior information with ongoing physician-outreach efforts can lead to a major leap in marketing effectiveness. Consider how a company hoping to expand the sales of a particular treatment in the U.S. can use big data analytics to design its digital-outreach campaign. The first cut of data would include all U.S. physicians who treat the disease in question. (See Exhibit 5.) That pool could then be narrowed (on the basis of physicians’ history) to those with a high probability of participating in a particular digital communication, whether that is an informational video or an e-CME program.

In our experience, this approach can allow companies to reduce the number of general communications by 80 to 90 percent, while maintaining the same number of successful interactions with physicians.

As digital channels are increasingly used, companies must ensure that the conversation with physicians is “seamless.” This means the rep or ICM will personalize and send the invitations to those identified physicians with whom they have a relationship.

Ensuring Successful Execution

Many companies have the information necessary to tailor outreach to individual physicians, but it’s also true that many lack the infrastructure and capabilities to use this information effectively. That creates a host of problems, including the failure to integrate MCM into the existing marketing effort and the poor customization of outreach to physicians. Understanding what is required to successfully implement a targeted MCM strategy is just as important as designing the strategy in the first place.

The following four components will go a long way toward ensuring that a company is able to implement and manage an MCM effort. Companies should also explore ways to energize the effort—including a major kick-start campaign focused on important new launches and key brands. Such an effort can be used to establish a baseline, set clear goals, and develop a comprehensive plan to build MCM capabilities.

Establish an MCM Center of Excellence

Many pharmaceutical companies have run successful MCM pilots but have not figured out how to scale up those tests. As a result, successes in one part of the business are rarely transplanted to other units, often leading to redundant efforts by different teams across various therapeutic areas or locations. One pharmaceutical company, for example, conducted an inventory of mobile-phone apps for physicians and patients and found that 70 different apps—many of which were nearly identical—had been developed in parallel, with one app developed separately in four different countries. Not only is this wasteful, it points to a lack of thoughtfulness in customizing the features, functionality, and even “mood” of the app—all of which should be carefully considered given the target audience, the message, and the action desired from the physician or patient.

A center of excellence for MCM—an organization that drives and coordinates the entire MCM effort—provides guidance on how the company’s core digital assets and IT systems can be leveraged, freeing local teams to focus on what is unique about their markets and brands. This approach can balance the need to be cost effective with the creativity essential to meet the needs of segments of one.

Rigorously Train Brand Teams

Brand teams play an essential part in successful MCM. They must incorporate MCM in their brand plans and provide MCM-ready content. In the past, in many companies, MCM never took off because brand teams employed only traditional tools in reaching out to physicians. Also, many MCM initiatives have suffered delayed updates of content—such as material for an e-CME program or a website—as well as content that was not designed specifically for the channels in question; rather, it was a mere recycling of traditional field-force material.

That’s why successful companies have embarked on a rigorous program to train their brand teams to produce MCM-ready content and to routinely include MCM in brand strategies. To overcome inertia, some companies go so far as to require brand teams to devote a certain minimum share of the marketing budget to digital channels. In addition, a mentoring program, in which MCM experts coach and tutor brand managers, can be a successful way to promote MCM capabilities within the brand teams.

Upgrade Systems and Governance Processes

Creating a seamless conversation with customers requires robust and accessible data on past interactions and integrated customer-relationship management (CRM) systems. Pharmaceutical companies must invest in systems that can combine data from face-to-face visits and digital interactions (including rates for opening e-mails and clicking through to links provided in e-mails) and that make that information available in near real time. All too often, however, CRM tools are not able to link information on digital and traditional communications, and analytics capabilities are nascent.

Legacy CRM systems, which have typically been customized for each pharmaceutical manufacturer and sometimes even for each division, cost tens of millions of dollars to implement and are cumbersome to maintain. These systems, however, are a poor fit for the constant experimentation with digital channels required in today’s market.

That’s why some companies have moved to newer CRM systems that use technology such as cloud-based systems and software as a service. These CRM systems are less customized than legacy systems but significantly more cost effective. And they can be integrated with more customized and nimble digital channels, such as apps and websites, for patients or physicians. For this approach to be effective, the savings from moving to this model must be invested in the development of analytical capabilities that link information across channels, brands, regions, and campaigns. At the same time, companies often will have to revisit existing processes and governance including budgeting, “ownership” of client relationships by sales reps or other functions, promotional-content review, and the way the company works with outside partners, including advertising agencies.

For instance, in most organizations, “digital” and MCM have different reporting structures even though they target the same customer with similar messages. The analytical capabilities required cut across brands, divisions, and locations, but the digital and analytical efforts are often funded on a brand-by-brand basis, yielding a variety of technologies, metrics, and vendor relationships—all of which complicates efforts to build a fundamental capability that can be scaled beyond a specific asset or campaign.

Measure Return on Investment

The lack of convincing proof that MCM pays off has damaged the reputation of these efforts within companies. Thus, it is critical for companies to create robust methods for tracking return on investment, a move that will help them understand which approaches have hit at least a minimum level of success (so they can be rolled out more broadly) and which have not (so they can be corrected).

Measuring ROI involves tracking KPIs such as click rates, number of users for a website or app, call durations, and physician satisfaction levels. But most pharmaceutical-industry MCM pilots have been too small to allow for a reliable ROI measurement, too brief for adequate testing, or designed in a way not suitable for measurement. Key shortcomings in pilot design have included the lack of a clear definition of the baseline performance and the failure to establish a control group of physicians to show how a marketing program will perform in the absence of MCM.

MCM is no longer a “nice to have” capability. In the current challenging pharmaceutical industry, MCM’s potential to boost revenues and cut costs are compelling reasons to make the institutional changes necessary for this new means of connecting with physicians in the digital world.

Companies certainly have the data right now to deliver on MCM. Effective marketing approaches can make use of that wealth of data, allowing pharmaceutical companies to tailor their content and channel mix to maximum effect. What many companies lack, however, is a plan for change and the organizational patience required to transform entrenched processes, incentives, and ways of thinking. Both elements are required in a highly connected world where success in reaching physicians and patients depends on the relevance of content and the quality of the interaction. The question now is whether the industry will make the investments required to build an MCM approach that yields reliable execution and healthy returns.