It’s often been said that women are the most underutilized asset in the world. Studies have shown that the economic inclusion of women is fundamental to reducing gender inequality and spurring overall economic growth. Women’s economic participation has been shown to have a multiplier effect: the economic empowerment of one woman ripples meaningfully to her children and family—even to entire communities and nations.

Still, women face a range of challenges—such as restrictions on the hours they can work and the types of jobs they’re allowed to take—that keep them from accessing opportunities in the traditional economy and being fully productive members of the workforce. Entrepreneurship thus provides an important means for women to empower themselves and define their own economic participation when other employment opportunities may not be available. The broader economic impact is substantial; in fact, if women and men participated equally as entrepreneurs, global GDP could rise by as much as 2 percent or $1.5 trillion, according to research by The Boston Consulting Group.

The reality, however, is that far more men than women start, sustain, and grow their own businesses. The underlying reasons for this imbalance are complex and varied, but they include differences in access to human, financial, and social capital. Unless these differences are addressed, the gender gap will likely remain wide, and global economic development and growth will not reach their full potential.

The specific focus of this report is on the importance of social capital for the success of female entrepreneurs. Both men and women need social capital—the access to networks that can support, connect, and mentor entrepreneurs—to successfully establish and run a business. But social capital’s particular importance for women—and how they can systematically develop it—isn’t well understood. The framework in this report provides a starting point for designing effective professional networks. Corporations, governments, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) should consider the principles we offer to ensure that conditions for success are built into programs that support female entrepreneurs and economic progress.

The Entrepreneurial Gender Gap

We define an entrepreneurial venture as an owner-managed business of any size. It could be a necessity-based venture, such as a woman selling goods in a market stall as the best available option to support her family, or an opportunity-based venture designed to capitalize on a market need or trend. Entrepreneurial ventures have three primary stages: start-up, sustainability, and growth. In examining social capital, we focus on the first two phases and define success as sustaining a business for three and a half years or longer.

Globally, women own 40 percent fewer businesses than men. The reason for this gender gap is twofold. First, women start fewer businesses than do men. According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) project, only 11 percent of women around the world start new businesses—30 percent less than men. Second, women have a lower success rate than men when it comes to sustaining a business. There is an additional 10 percent entrepreneurship gender gap in the rates at which women and men sustain their businesses, as measured by the proportion of sustained businesses versus new businesses. While the gender gap in the start-up rate has decreased over the past few years, a similar decrease has not been seen in the success rate. Not addressing the success rate of female-owned businesses cuts in half the potential global GDP increase of $1.5 trillion, as more mature businesses are more likely to grow and hire additional people.

Three types of capital—human, financial, and social—are crucial for starting and sustaining an entrepreneurial venture. Human capital refers to the skills, business knowledge, and experience an entrepreneur needs to draw on. Financial capital refers to the necessary monetary resources. And social capital, as mentioned earlier, refers to access to networks that provide information and resources, as well as access to formal and informal mentor relationships.

These three types of capital are interlinked—and women tend to be less likely than men to have access to them all. As a result, women are less able to fully take advantage of the opportunities that are available to them. Many valuable initiatives are under way to provide female entrepreneurs with greater access to human and financial capital. Although gender gaps still remain, much of the progress that has been made to date is due to these efforts. Social capital is equally important, but it is less well understood.

The Power of Social Capital

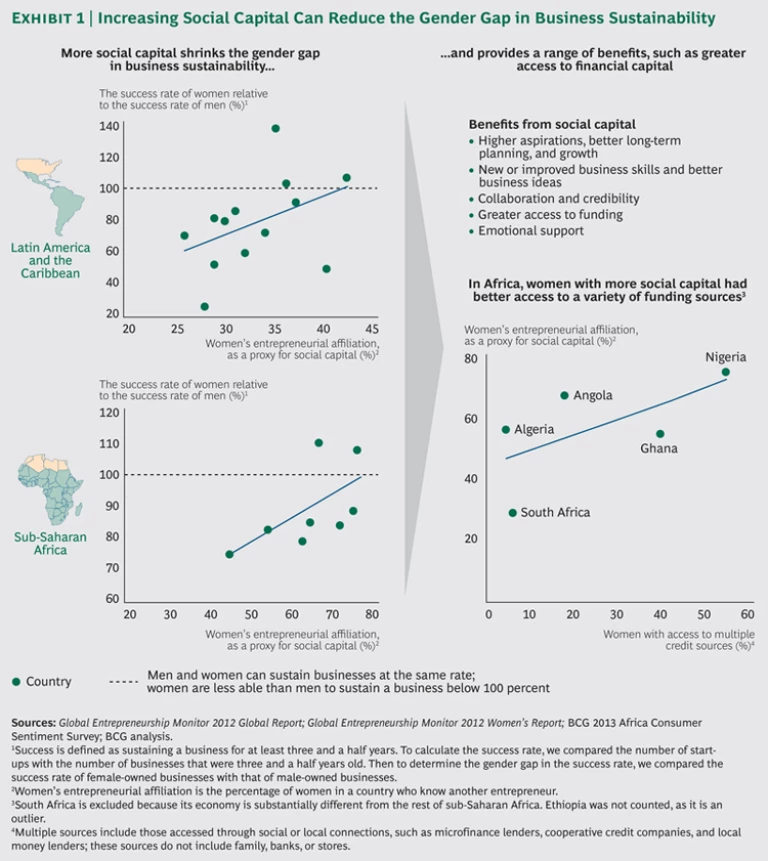

Although less research has been done on social capital than on other forms of capital, the data suggests that social capital has a significant impact on the success of female entrepreneurs. Higher rates of entrepreneurial affiliation—defined as knowing another entrepreneur and a proxy for social capital—are linked to smaller gender gaps in business sustainability in developing countries. For example, data from Latin America and the Caribbean shows that a 10 percent increase in women’s entrepreneurial affiliation appears to reduce the sustainability gap between genders by as much as 25 percent. (See Exhibit 1.)

To better understand the impact of having social capital, we interviewed decision makers at 13 organizations around the world whose mission is to support female entrepreneurship. These interviews with experts in the field reinforced that social capital supports female entrepreneurs in many ways, ultimately helping them to run and grow their businesses better. The benefits of social capital include higher aspirations and better long-term planning, which result in growth; new or improved business skills and better business ideas; collaboration and credibility; greater access to funding; and emotional support. Let’s look at these benefits more closely.

Aspirations, Long-Term Planning, and Growth. According to the experts we spoke with, social capital enables female entrepreneurs to increase their aspirations, envision long-term plans, and set more ambitious growth targets for their businesses. According to GEM, the growth aspirations of female entrepreneurs typically lag behind those of their male peers. The percentage of male entrepreneurs projecting growth over a five-year period and the hiring of six or more employees is 7 to 9 percentage points higher than the percentage of female business owners making the same prediction. Role models and mentors encourage, inspire, and build confidence in female entrepreneurs, helping them envision long-term success, develop skills for growing their businesses, and cultivate professional networks.

The Asia Foundation , an international development organization, found that women in Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand who use established networks and associations are 24 percent more likely to plan for growth than women who don’t use such resources. In addition, the businesses of women using networks and associations are, on average, 38 percent larger than those of women who don’t access such resources. The need to acknowledge the benefits of social capital is highlighted by the Asia Foundation’s research, which found that a higher percentage of female business owners than male business owners in these countries never interact with business associations.

Going for Growth , an organization for female entrepreneurs in Ireland, offers peer-based programs that include regular roundtables led by successful women who explore growth-related topics. In a recent program, three-quarters of the participants reported that their sales had risen by an average of 15 percent, more than half of the women said that they had hired additional employees, and the number of businesses exporting goods had increased. A Going for Growth pilot was recently set up in Finland, adding an international dimension to the organization to further support its aim of connecting a diverse group of female entrepreneurs, helping them grow, learn, network, and do business together.

New or Improved Business Skills and Better Business Ideas. Through mentor relationships and by sharing the experiences of other entrepreneurs, female business owners learn new business skills, gain valuable insights, and receive feedback on business innovation, processes, and ideas. The Cherie Blair Foundation for Women has a program that pairs female entrepreneurs with knowledgeable mentors, and it reports that 96 percent of its entrepreneurs increase their innovation skills. (See “Social Capital in Action.”)

SOCIAL CAPITAL IN ACTION

The Cherie Blair Foundation for Women’s mission is to build the confidence and capabilities of female entrepreneurs and to improve their access to financial capital. The foundation’s global Internet-based program matches women with mentors, who help the entrepreneurs set personal business goals, develop business plans, and tackle difficult problems. The mentorship pairing is complemented by an online community that allows program participants and alumni to collaborate, share ideas, and learn from each other. The women who participate see real business results. Ninety-six percent report a greater ability to innovate, 94 percent say that they’ve improved their business skills, and 93 percent have achieved a business goal through the program.

A successful participant in the foundation’s mentorship program is Zeti, whose story demonstrates the importance of social capital. Zeti started making cakes and cookies from her home in Malaysia to sell during religious holidays. When this mother of six joined the Cherie Blair Foundation for Women’s program, she was pregnant and, like many other entrepreneurs, felt isolated working alone on her small enterprise. Zeti was connected with a strategy and management consultant from the UK. By working with a mentor, she developed a business strategy, financial plan, and ways to promote her products. Her mentor helped her think of ways to expand and pushed her to enter new markets. Zeti learned how to use the Internet to find new products and connect with new customers.

Using her new skills, Zeti expanded her baking business and increased revenues thirteenfold. Busy and turning away orders, Zeti has hired an employee to help her. Zeti hopes to open a cake shop in Kuala Lumpur and eventually sell her delicacies around the world.

Perhaps even more informative are the stories of female entrepreneurs themselves. California-based Sue was at a turning point and decided that she was ready to launch her own bakery. She found the turmoil of navigating the necessary steps to run her business daunting at times and lonely. It was through a network of female entrepreneurs, supported by an organization called Smarty , that she was able to participate in “brain circles” and other programs and learn from experienced leaders and other entrepreneurs. The feedback, advice, and emotional support from women in the network facing similar challenges ultimately helped her launch a new website and make her bakery successful.

Collaboration and Credibility. A network can lead to valuable connections and confer credibility on a new venture, ultimately providing opportunities for improved operations and increased business scale. For instance, The BOMA Project , which helps Kenyan women in extreme poverty start their own businesses, has created an informal network of BOMA alumni who band together to buy supplies more cheaply from wholesalers in remote villages, achieving cost savings that would be unavailable to them individually. Similarly, WEConnect International provides legitimacy and game-changing growth opportunities by connecting female-owned businesses with global corporate-purchasing organizations that individual entrepreneurs wouldn’t otherwise have access to.

Greater Access to Funding. The connections and credibility that networks deliver can improve access to financing. According to BCG data on Africa, female entrepreneurs with more social capital also have greater access to more varied sources of credit, such as microfinancing and loans from cooperatives. Opportunity International provides loans, savings programs, insurance, and other financial services, as well as business training to entrepreneurs in 22 developing countries. Ninety-one percent of those loans are to women. New applicants must be approved by their local loan group, so women who have built social capital and thereby have greater credibility within their communities are more likely to be approved.

Endeavor Global is an organization that accelerates the growth of high-impact ventures by providing entrepreneurs with social capital, including a network of investors. The organization made about 2,700 introductions in 2012 and 2013, connecting entrepreneurs and investors. The connections bring tangible benefits. For instance, Endeavor entrepreneurs raised $332 million in debt and equity in 2012 alone. Given that a lack of financial capital poses a significant constraint across all phases of entrepreneurship, improving access to funding is a vital enabler of success.

Emotional Support. Starting a business can be difficult, isolating, and stressful—especially for women who are balancing their ventures with family obligations, at times in impoverished conditions. Networks provide valuable support that helps start and sustain a business. For these reasons, Village Enterprise and BOMA make sure that a group of three women run a single business: no one has to balance family and business demands alone. (See “Lifting Women Out of Poverty.”)

LIFTING WOMEN OUT OF POVERTY

Village Enterprise and The BOMA Project help women and their families escape extreme poverty. Village Enterprise equips women with the resources they need to create sustainable businesses in sub-Saharan Africa. BOMA helps women generate a sustainable income in the arid lands of northern Kenya.

The programs take a similar approach—and the role of social capital is critical. Both organizations make sure that groups of three female entrepreneurs run a single business. This way, no one has to balance family and business demands alone, and having partners shields each woman from family requests for earnings and loans. This structure by itself also assures built-in social capital.

The programs also provide female entrepreneurs with cash grants, extensive training in business skills and financial literacy, and mentorship. The three-woman units join larger business-savings groups, which provide access to capital for business expansion and emergencies as well as greater purchasing power. The larger networks also provide essential moral support, new-business information and opportunities, and expanded financial services.

The programs provide substantial, sustainable benefits to impoverished families. At Village Enterprise, 75 percent of the businesses are still operating after four years. After only one year, savings groups (made up of ten businesses) have typically saved more than $850—six times the seed capital of only one business in Uganda. According to program alumni and managers, the overwhelming success factor is the synergy among a group’s members and their support of each other. BOMA reports similar levels of success. All but 1 percent of BOMA businesses are still operating after one year, and 93 percent are still running after three years. The businesses are also profitable. On average, the value of these businesses doubles in one year and more than triples after three years.

Given the benefits of social capital, we believe that solutions aimed at supporting female entrepreneurs should seek to incorporate it in a systematic, structured way.

The “Three I” Framework of Social Capital

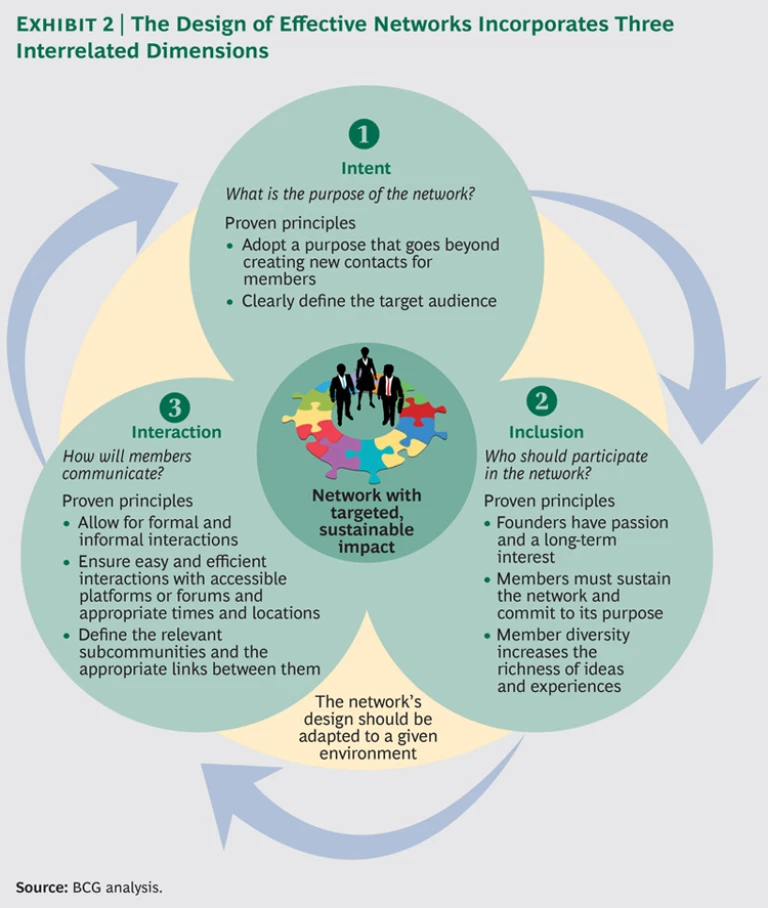

The programs we examined use social capital to achieve tangible results for female entrepreneurs, allowing them to reach their targets and empowering them in a sustainable way. It’s important to note, however, that the mere existence of networks does not convey benefits or ensure results. Networks must be designed, managed, and sustained according to proven principles. Through interviews with experts and program managers, we found that effective networks consider three interrelated dimensions: intent, inclusion, and interaction. (See Exhibit 2.)

Intent: What is the purpose of the network? Effective networks must have a purpose that is clearly defined and goes beyond simply creating new contacts for its members. Networks must add enough value that membership and participation become priorities and relationships develop. Therefore, the purpose of successful networks often includes increasing access to human or financial capital or helping members develop tangible business goals. Endeavor’s mission, for example, is to be a catalyst for long-term economic growth by selecting and mentoring high-impact entrepreneurs from around the world and accelerating the growth of their ventures. Endeavor achieves its purpose by providing business advice and better access to financial capital through its mentor and investor network. As the Endeavor example points out, a network’s target audience must be clearly defined, and the network itself must be explicitly designed to achieve its stated purpose.

Inclusion: Who should participate in the network? Since the power of a network stems from its participants, three factors are critical for success: the right founder, committed members with time to invest, and member diversity. Formal networks and mentorship programs require major investments of time and effort to maintain and, as a result, often struggle to become long-term, self-sustaining entities. Therefore, passion and energy are integral to their success. That’s why the most effective networks have founders with a long-term interest in developing and running the program or with the ability to empower members to take ownership of the network and sustain it. A founder can be an individual, an NGO, a corporation, or another organization with a long-term interest and presence in the community, such as a bank or hospital, but the founder should have the interest to sustain the network through the start-up phase and beyond.

Just as important, the members themselves must find the resources and develop the strategies to sustain a network—and commit to its purpose. We have observed that networks use a number of approaches to increase member commitment:

- Charging membership fees

- Interviewing applicants or asking alumni for recommendations to ensure the right member qualities and mindset

- Establishing attendance policies that commit members to be present at a minimum number of meetings per year

Finally, diversity can add significant value. Networks should aim to attract members from diverse backgrounds to increase the richness of ideas and experiences. Prospective members might include a mix of new entrepreneurs and more established business owners, successful role models, and subject matter experts—ideally from a variety of cultures. This diversity will likely enhance the meeting discussions and increase the variety and depth of available business skills and feedback that members receive. Our interviews suggest that when networks are too narrow in their membership, their utility for members decreases over time.

Interaction: How will members communicate? Networks must decide how interactions will be managed and how members will request assistance, exchange ideas, and support each other.

The structure of networks should allow for both formal and informal interactions. Formal interactions build a self-sustaining network, but members must also be able to use the network informally as needed. For instance, the Cherie Blair Foundation for Women has formal mentor programs, but it also encourages informal relationships, idea exchanges, and collaboration through its online forum for members and alumni. Participants appreciate the flexibility of the more informal online option, but they regard both parts of the program as critical for success—each enhancing the impact of the other.

Easy and efficient interaction is a prerequisite for member participation and commitment. Successful programs do their best to adapt to member needs in terms of the exchange platforms used and the cadence of meetings. For instance, the Cherie Blair Foundation for Women’s online forum allows members to access advice on demand, whenever they have an Internet connection, making participation easy.

Finally, defining potential layers and subcommunities, their structure, and how they should connect and interact can also be a source of value. Networks aiming for impact on a larger scale may need to link members to resources at the local and regional levels and beyond—especially to create and capitalize on growth opportunities. For instance, female entrepreneurs who win larger supply contracts through WEConnect’s global sourcing program can subcontract parts of their contracts to other female entrepreneurs in the network, thus growing their businesses by fulfilling larger contracts that they could not take on individually. Networks that operate in this fashion have the potential to significantly increase the size and scope of their impact.

Across all of these dimensions, it is vital for the design of a network to account for and adapt to the local culture, norms, needs, and infrastructure of a given environment. A female entrepreneur in Africa may need access to a savings account, whereas one in the U.S. may need training in how to evaluate a potential investment. There is no easy, one-size-fits-all solution for all circumstances.

Looking Forward

Despite the progress to date, continued efforts must be made to empower female entrepreneurs and close the gender gap in economic opportunity. Although women today have greater access to human and financial capital, the gender gap in starting and sustaining a business remains wide.

BCG’s analysis of existing support programs reveals the importance of social capital and the significant benefits that networks and mentors deliver. The challenge is how to create networks with true, sustainable impact. The framework we’ve outlined is a starting point for designing successful networks. The framework provides a platform for the continued sharing of best practices and is an important call to action for stakeholders around the world. We urge organizations to consider the importance of female entrepreneurs and the role social capital plays in their success. Governments and NGOs should capitalize on the power of social capital when funding and developing support programs, with a particular focus on female entrepreneurs whose businesses hold the potential to grow and create jobs. Corporations should seek opportunities to expand their partnerships with networks of female entrepreneurs to enable mutually beneficial growth.

By recognizing the importance of social capital for women and by helping them develop it systematically, we can continue to close the gender gap in global entrepreneurship. By working together, we can help women around the world achieve their economic potential, which in turn could lift the global economy.