Social disadvantage is extremely hard to overcome. In the UK, for example, children who have spent time in protective care are 9 times more likely to be expelled from school, 6 times less likely to attend university, 40 times more likely to be imprisoned before reaching the age of 21, and 50 times more likely to be homeless later in life. And the number of UK children in care is growing, rising 12 percent in the last five years. The numbers are depressingly similar in other countries around the world.

Yet child protection agencies often face enormous hurdles: tight budgets, large workloads, inadequately trained workers, lax supervision, and a culture of box-ticking compliance rather than the use of professional judgment. Although not all agencies have these problems, those that do are subject to consequences that can be fatal. High-profile cases of heartbreaking abuse and neglect make the headlines all too often.

In the past, reform efforts have focused on structural solutions such as new legislation, agency reorganization, and national oversight reforms rather than initiatives that address a greater underlying problem: inadequate workforce quality.

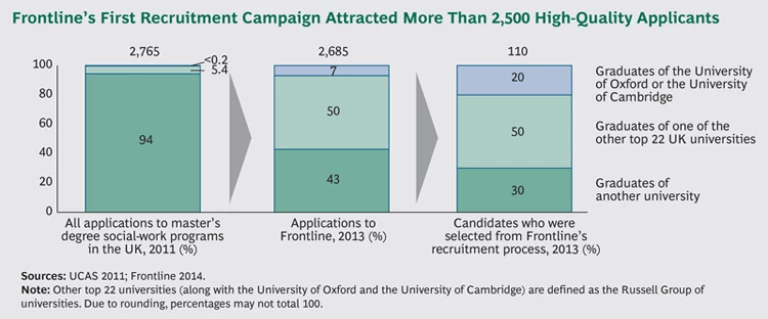

An outstanding social worker can transform the lives of disadvantaged children and help them reach their full potential. But attracting high-caliber job candidates is not easy. Child-welfare social work is often perceived as a low-prestige profession among top-university graduates, and recruiting is difficult. In the UK, less than 0.2 percent of the 2,765 students starting master’s level courses in social work in 2011 went to the University of Cambridge or the University of Oxford as undergraduates, and only 5.4 percent attended one of Britain’s other 22 top universities (the so-called Russell Group). While having attended a top university is a very narrow measure of one’s potential to be a great social worker, it at least highlights the sector’s recruiting challenge. In comparison, Oxford and Cambridge undergraduates alone made up almost 10 percent of the applicants to the 2009 Teach First teacher-training program.

Poor and uneven training exacerbates the problem, leaving social workers unprepared for the front line. In a 2012 survey, 70 percent of 600 industry professionals reported that newly qualified social workers were entering the profession with insufficient skills and experience to begin practicing.

Frontline: Focusing on the Workforce

Frontline was founded almost two years ago, in 2013, to tackle these problems by improving the quality of new child-welfare social workers. Supported by The Boston Consulting Group and jointly funded by the UK government and philanthropic donations, Frontline runs a two-year training and development program that leads to a master’s degree in social work. The program was inspired by the success of Teach First, which increased the number of top graduates working in inner-city schools and boosted the prestige of teaching as a profession.

Delivered in partnership with the University of Bedfordshire, The Institute for Family Therapy, and the King’s College London Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, Frontline’s program combines an innovative curriculum, a five-week summer institute, 12 months of supervised on-the-job training, and an ongoing leadership-development course.

To ensure strong support and supervision—critical components missing from many existing social-work training programs—first-year participants join a working unit that provides an unprecedented level of intensive support. Each unit has four participants and is led by a senior experienced practitioner called a consultant social worker (CSW). With Frontline’s dedicated training and support, the CSWs closely coordinate their work with the participants’ academic training. This innovative model is unique to Frontline and draws heavily on the experiences of a small number of experimental local authorities and other professions such as medicine. By the end of their first year, participants have completed more than 200 days of on-the-job training—more than is offered as part of any other route to social work—and almost 50 full classroom days.

Upon completion of the program’s first year, participants are qualified social workers, ready to take statutory responsibility for their own work on the front line. In their second year, they join an existing social-work team in the region in which they trained, where they continue to work under supervision and their performance is assessed. This transition allows them to work within the same local-government jurisdictions and with the same colleagues.

Rebranding Social Work as a Compelling Career Choice

Frontline runs the only nationally coordinated recruiting campaign for social work in England. To make sure that it attracts high-quality applicants, Frontline targeted the country’s top graduates and people looking for new careers and applied a rigorous selection process comparable to that used by leading corporations and public-sector programs.

To compete for top talent in the highly competitive national labor market, Frontline had to reposition social work as the rewarding career choice it truly is. Using a mix of marketing and educational efforts, Frontline explained to potential recruits what the role actually entails and outlined a compelling value proposition: an opportunity to take on responsibilities quickly, develop leadership skills, gain experience outside the academic environment, and make a real difference in the lives of vulnerable young people.

Working with leading design and marketing agencies from the corporate world, Frontline produced a branded campaign with slogans such as “Get the Right Work-Life Balance: Their Life, Your Work,” as well as videos and extensive media coverage. Frontline’s first campaign was recognized by the recruiting industry, winning the “best attraction strategy” award at the Association of Graduate Recruiters annual ceremony and ranking highest (seventy-sixth) among new entrants in The Times Top 100 Graduate Employers list.

More important, Frontline’s first recruitment campaign to fill 100 positions attracted more than 2,500 high-quality applicants. More than 70 percent of the chosen candidates had graduated from one of the UK’s leading universities—far more than the scant 6 percent that began master’s degree studies in social work in 2011. (See the exhibit below.)

The Frontline Difference

Launched just 15 months ago, Frontline’s early success and positive press have generated interest both locally and internationally. The UK government is now looking for ways to apply similar models to other troubled professions such as adult-welfare social services and police work. Given the likely launch of such programs, it is worth noting some of the factors that figure in Frontline’s success, including the following:

- Independence. Frontline’s outsider status allowed it to take risks and challenge the status quo. Particularly in its earliest phase, Frontline faced stiff resistance from a variety of stakeholders. Although the program leadership had respect for their views, Frontline challenged them and adopted an innovative approach—a task that would have been far harder had the charge been led by insiders deeply embedded in the sector.

- Focus. As an outsider with a clear mission, Frontline was able to act with a singular focus that insider initiatives often struggle to achieve given the inherent distractions that originate in the environment from which they have grown.

- A Coalition of Supporters and Leaders. Frontline built a coalition of leaders and supporters who fully believed in the program’s value. This coalition included politicians from all parties, academics, employers, charitable organizations, and—unique for British child-welfare social services—private businesses.

- A Balance of Boldness and Consensus. Frontline had to deal with vested interests, political issues, and industry concerns while building cross-party support. To avoid undue risk, Frontline focused its innovations on a small number of very high-value areas—but only after detailed research and extensive consultation with all stakeholders.

- Scale. Too often, new social initiatives succeed in solving a local problem but struggle when they apply the same solutions on a larger scale. From the start, Frontline was designed to be scalable. The recruitment campaign is already national, and the program’s design can be readily replicated in other regions.

- Value for Money. In an era of tight fiscal budgets, Frontline has been careful to focus on low-cost, high-value innovations. In addition to ensuring the workforce readiness of its graduates, Frontline aims to keep its costs per qualified social worker at levels that are broadly comparable with those of other social-work entry programs (as well as Teach First). From the UK government’s perspective, Frontline’s ability to draw on the support of charitable organizations and private business has further enhanced its value proposition.

- Strong Leadership. Building a disruptive business model in any sector is not for the fainthearted. Seeing it through to fruition requires a clear vision and strong leadership, as well as personal resilience, determination, and sheer grit. Both Josh MacAlister, Frontline’s founder and CEO, and Lord Adonis, Frontline’s chairman and an early champion, embody these characteristics.

By focusing on one of the underlying causes of poor child-protection outcomes—inadequate workforce quality—Frontline was able to approach the problem in an innovative way and transformed the way child-welfare social workers are recruited and developed. Now, the program is well on the path to improving the future of society’s most vulnerable children.

Academics who taught at this past summer’s institute—including former skeptics—expressed their positive impressions of the high-caliber participants and the intensity and focus of the training delivered. The program has received extensive positive news coverage and has been endorsed by all three of the UK’s major political parties, as well as by Prime Minister David Cameron, who recorded a supportive video message for the opening day of the summer institute.