The U.S. beer market is open, freely competitive, and driven by consumer choice. Brewers who capture the hearts of consumers are the most likely to succeed. Those who miss shifts in consumer identities, norms, attitudes, and tastes will suffer.

The success of small brewers making craft beers is proof of these points. Despite fears that small brewers can’t compete against the scale and reach of large, mass-market brewers, the opposite has proved to be true. The popularity of craft beers supplied by small brewers has exploded, rising on the strength of consumer demand. Ironically, small brewers’ ability to reach more drinkers has been enabled by the open U.S. beer-distribution system—a system that was once thought to lock out smaller players.

The economics of the U.S. beer business conveys significant advantages to those with scale. But, as it turns out, subscale small brewers are also (unexpectedly) the beneficiaries of the advantages afforded major domestic brewers. The reason: they can leverage an effective route-to-market distribution system that was built by distributors and larger brewers over the decades. This open distribution system enables small brewers to avoid significant, if not prohibitive, costs to entry, while also gaining deep access to large and small retailers.

Our findings have implications for all U.S. brewers. All brewers need to attract consumers, of course. Even incumbents with strong distribution networks are not insulated from the changing tastes and demands of consumers and retailers. Small brewers seeking to break into the market must recognize that they ultimately depend on consumer loyalty and that the distribution costs are not the impediment they seem to think they are. In fact, thanks to piggybacking on independent distribution networks supported largely by the economics of large domestic and import brewers, small brewers avoid much higher distribution costs. And regulators need not worry about the barriers to entry for market newcomers given their recent success and ability to leverage the industry distribution system.

The Rise of Small Brewers

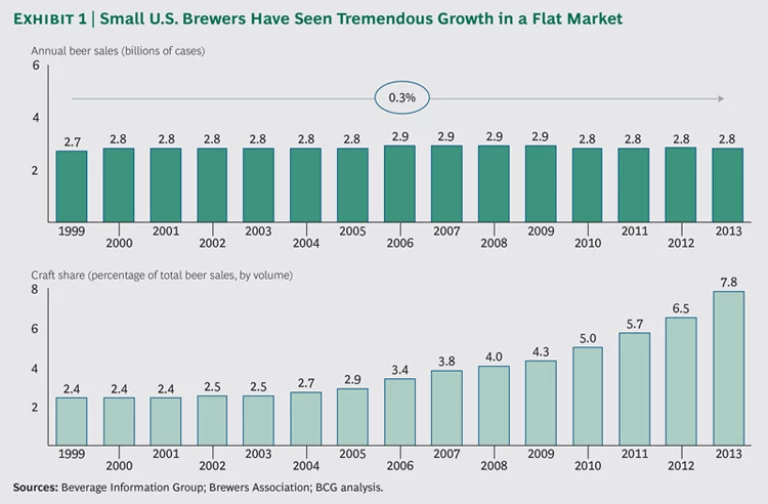

Consumption of imported and domestic beer in the U.S. has remained relatively flat since 1999. Total U.S. sales volumes rose just 0.3 percent year-over-year over the full period, with a mild decline during the past five years. (See Exhibit 1.)

Within that market, the U.S. craft beer segment has seen tremendous growth. According to the Brewers Association, craft beer production increased more than 80 percent in just the past five years, from 117 million cases in 2008 to 215 million cases in 2013. During that same period, small brewers’ volume share of the overall beer market rose from 4.0 percent to 7.8 percent. In addition, according to the National Beer Wholesalers Association, the total number of craft breweries in the U.S. has now reached historic levels—growing from 350 in 1991, to 1,499 in 2001, to more than 2,500 today.

Clearly, consumer preferences have been the main engine driving this growth. Craft beers are riding a wave in which consumers are “trading up” across all consumer categories to brands and products that are perceived as having strong authenticity and higher quality, and as being more relevant to specific consumers’ attitudes, values, and lifestyle. This preference for trading up persisted even during the most recent recession.

The Dynamics of Distribution

Demand without distribution, of course, would leave small brewers without sales. Thanks to the open structure of the three-tier distribution system, small brewers can satisfy consumer demand.

The Boston Consulting Group has studied direct store delivery (DSD) across multiple categories for more than 20 years, often in conjunction with the Grocery Manufacturers Association. We have consistently seen that in U.S. categories with supplier-owned DSD systems—such as ice cream, soda, and snacks—suppliers enjoy significant benefits of local scale. And large players have multiple advantages, such as being able to make more frequent deliveries, reach smaller stores, introduce new products more quickly, and set up in-store displays, to name just a few. All these benefits combine into significant competitive advantage for the larger players in DSD categories.

When it comes to beer, however, distributors are independent from brewers. A brewery can demand certain quality standards from its distributors, but it cannot demand absolute product loyalty. In fact, distributors are more than independent—they have certain franchise rights in perpetuity, protected by the state, for the brands they distribute. These protections prevent breweries from using their scale to extract advantages from the distribution system the way that DSD suppliers do.

At the same time, the independence of the distributors creates the opportunity for smaller brewers to “get on trucks” and achieve distribution at a much lower cost per unit than they would otherwise have to pay. These distribution costs are considerable. A recent economic impact report from the National Beer Wholesalers Association estimates that the cost of wages and salaries associated with operating the entire U.S. beer distribution system is approximately $10 billion in annual expenses. In total, U.S. beer distributors employ more than 130,000 full-time equivalents and service more than 500,000 retail outlets.

The Value of Open Distribution

The ability of small brewers to gain access to the marketplace through independent distributors is a major reason that small brewers are able to exist at all. Considering that only the top ten small brewers generate more than $20 million in revenues annually, according to the Craft Brew Alliance, building a stand-alone distribution system would be cost prohibitive. Without independent distributors, most small brewers would have to cope with far less access to the market and consumers, and far lower growth rates.

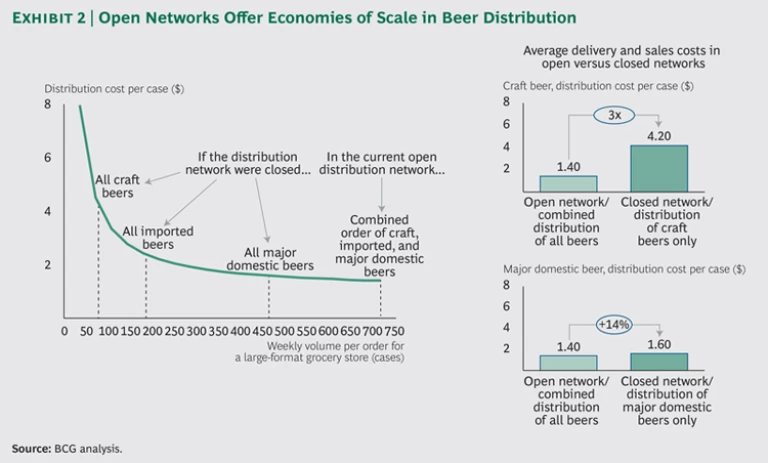

How valuable is this access, economically speaking? To illustrate the economics, we applied BCG’s proprietary DSD economic modeling approach to the costs of distributing beer to large-format grocery stores. (See Exhibit 2.) Using an economic model of the costs of distributing and servicing a set of like stores, we estimated the costs for different types of breweries under today’s open distribution system. Then we compared that result to what the costs would be if the distribution system were not open—that is, a system that restricted the types of products permitted on trucks to those produced or sanctioned by a major brewer.

We found that in today’s open distribution system, the average delivery and sales cost for a distributor supplying craft beers, imported beers, and a major national beer company’s portfolio to a large-format grocery store is $1.40 a case. If the major national brewer were to build a dedicated closed distribution system, its delivery and sales costs would only increase 14 percent—from $1.40 per case to $1.60 per case.

On the other hand, if craft beer suppliers did not have the benefits of scale afforded by combined distribution of their craft beers with imported beers and the domestic beers of a large national brewer, their distribution costs would be triple what they are today—that is, $4.20 per case. And that’s not even including costs such as warehousing, administration, and distributor margin. Given the moderate margins of small brewers, this cost disadvantage would likely get passed through to the consumer—making many craft beers far more expensive and small breweries less competitive.

Ongoing Challenges

This is not to say that all is rosy for small brewers. Open marketplaces, in which consumer choice is king, can be brutal. Small brewers are challenged when their own success invites more entrants. Most consumers aren’t looking for the fifteenth version of a strong-tasting hoppy India pale ale. In fact, it is not uncommon for sales to drop off precipitously after the arrival of the first few brands in a particular style or position. This means that most of the me-too craft products deliver low velocity (while taking up valuable shelf space) at retail outlets and low revenues at bars. Once the excitement and newness wears off, retailers, restaurants, and bars may cut their craft beer offerings.

Further, with such an abundance of craft beer options, me-too small brewers face challenges engaging retailers and distributors. Retailers don’t want to carry what distributors don’t carry—and vice versa. Without a differentiated position, small brewers will find it hard to create the coordinated momentum required to break through.

Distributors are also increasingly challenged by the complexity and costs inherent in handling low-performing items that don’t have a meaningful consumer following. In 2007, the average beer distributor carried 262 different SKUs, according to the National Beer Wholesalers Association; by 2013, the average beer distributor carried 657 SKUs. Beer distributors are starting to be more demanding in terms of what they bring into their warehouses, add to their computer systems, and support in the marketplace.

The Implications

Our view is that success in the beer industry still rests fundamentally with consumer demand. Further, the current open structure of the three-tier distribution system has been a fundamental enabler of growth in the craft beer segment.

Several other key findings also emerged for major players in the industry:

Regulators of the beer industry, which is one of the most highly regulated industries in the U.S., should recognize that the marketplace is working. And they should be skeptical of complaints (legal and otherwise) that the marketplace favors only large players.

Large brewers are also at the mercy of the consumer and retailer. With all the options available, if the brands in large brewers’ sizable portfolios don’t hit the mark perfectly with today’s consumer, sales will decline. History is replete with examples of once-large brands and brewers that have fallen by the wayside because they couldn’t keep up with the market.

Small brewers must build their brands in order to generate sufficient demand to win (and retain) the space they occupy in stores and justify the complexity they add to the work of retailers and distributors. Doing so requires strengthening local demand and also offering products that are differentiated enough to cut through the clutter and compelling enough to convert trial drinkers to loyal ones. If they can do that, small brewers—aided by an open distribution system—will continue to enjoy success.