Goods labeled organic, natural, ecological, and fair trade are no longer a niche in the food, personal-care, and household products sectors. These goods have entered mainstream retailers and become a large part of the market, with a broad base of consumers now purchasing them. In an otherwise stagnant industry, these “responsible consumption” (RC) products represent a major area of profitable growth.

The Boston Consulting Group has worked with market research company Information Resources Inc. to analyze point-of-sale data from nearly all retail chains in the U.S. (grocery, convenience, department, and wholesale-club stores). Not only do RC products account for 15 percent of all sales in these chains but also sales have grown about 9 percent annually in the past three years—making up 70 percent of total growth. Similar turnover and growth levels are expected across developed markets. Global surveys point to future growth as well, as most consumers intend to expand the number of categories in which they seek out RC products.

Most of this growth, however, is going not to A brands—the major product brands—but to specialty brands and to both specialty and conventional retailers. Most A-brand manufacturers, in fact, have weak or nonexistent offerings in this area. Continued inaction may cost A brands one-third of their current consumers over the next few years.

While A brands bring major scale and distribution advantages to the table, consumers are less likely to trust them when it comes to RC products. To build trust while leveraging these advantages, A brands can either acquire a specialty brand and grant it considerable autonomy or build an RC brand internally with external validation. A third option is to embrace “responsible” criteria for the entire A brand. Any of these options is preferable to maintaining a wait-and-see approach.

A Major New Area of Sales

In the 1970s, a number of products emerged that catered to consumers concerned about the environmental and health effects of conventional mass-consumer products. Organic products—or bio products, as they were sometimes called—were grown without chemical pesticides or other aggressive farming practices, and natural foods had no artificial ingredients. Ecological, or eco, products were packaged in a way that would minimize the impact on the environment. Over time, this consciousness expanded to social concerns, leading to production that minimized unsafe working conditions and exploitative treatment of farmers and employees. Fair, fair-trade, and social labels joined the ranks. These concerns extended to personal-care and household-cleaning products, whose makers promised to avoid harsh chemicals and promote the sustainability of natural resources. Most recently, local labels have come into play, as locally grown and produced items are winning consumer allegiance—often through loosely organized farmers’ markets.

The early customers for “responsible consumption” (RC) products often had to compromise on quality. Fruit came with blemishes, vegetables were undersized, shampoo lathered poorly, and detergents left more grime. Only small numbers of engaged people were willing to accept these goods, and they could buy them mainly in small retail outlets that were devoted to the cause. It was a tiny niche that ebbed and flowed with public sentiment.

What was a niche has now moved into the mainstream. RC products are now of higher quality and are increasingly available in large retail chains, often next to their conventional counterparts. RC specialty manufacturers, such as Seventh Generation and Aveda, have grown and expanded their product portfolios. Whole Foods Market has spurred the growth of large RC retailers with comprehensive offerings in the U.S., and in Europe the established grocery chains have moved aggressively into this area.

We can see the growing popularity of these products in surveys. BCG has monitored “green” consumer sentiment around the world since 2009. In the most recent survey, conducted in 2013, we asked consumers, “How systematically do you currently buy ‘responsible’ products or services?” In developed countries, an average 8 percent of respondents said that they regularly buy RC products in most product categories, and 66 percent buy them at least occasionally. Of these groups, more than half said that they expect to extend these purchases to other categories in the future. RC products are more popular in Italy, Spain, and Japan; their popularity in the U.S. is average, and it’s a bit lower in the UK, France, and the Netherlands. Across the food, personal-care, and household-care sectors, 50 to 70 percent of consumers claim they have bought RC products.

These results, although important, have not been enough to convince most business leaders in fast-moving consumer goods to take the RC plunge. What does “occasionally” really mean? They wonder whether consumers will really “walk the talk.” In the absence of hard data on consumers’ actual buying behavior, most companies have stuck with their traditional offerings and have held back from any major investments in this area.

We set out to generate hard data. In collaboration with Information Resources Inc. (IRI), a major market-research firm, we drew on a database of nearly all U.S. retail sales. We randomly selected 20 major categories in the food, personal-care, and household-care sectors, including coffee, shampoo, laundry detergent, and dog food. We listed all the SKUs with material sales and studied them to identify the various RC claims. (For details on our investigations, see “About the Research.”)

ABOUT THE RESEARCH

Our goal was to understand the size, growth, and price premiums of RC products in the grocery market—as well as what motivates consumers to choose them. In order to do so, we executed SKU-level analysis of 20 U.S. retail categories, specific-category “deep dives” in the U.S. and European markets, a consumer survey, and focus groups in the U.S. and France.

SKU-Level Analysis. We conducted this analysis using IRI retail-sales data from the U.S. The data includes sales numbers, price per product, product size, and a simple categorization for organic and natural products. We randomly selected 20 categories in the food, personal-care, and household-care sectors. Excluding the long tail of low-selling SKUs, we looked at products amounting to 80 percent of 2013 sales—about 10,000 SKUs—and classified all claims on the product packages using product images. Based on this classification, we could analyze penetration, growth, and premiums in the market.

These analyses actually underestimate penetration, growth, and premiums, because IRI data is sanitized for private-label sales, which means that private-label sales cannot be classified as RC products. IRI does provide a separate organic and natural classification for food categories with private labels, but not local, eco, fair, or social—so there is no RC allowance in nonfood categories. Therefore, penetration and growth in the market is driven only by A brands (the major product brands) and specialty brands—except for food, which includes the private-label sales of organic and natural products. Since private-label premiums are higher than A brand premiums—based on quantitative analyses of food categories and qualitative analyses of European and U.S. retailers—the average price premium is underestimated.

Category-Specific Deep Dives. We performed category-specific deep-dive immersive analysis in U.S. and European markets to check quantitative analyses and provide more details. We also conducted an extensive press search to help extend the U.S. numbers in European markets, conducted research on the breadth of RC product offerings in European retail stores, and carried out a few country deep dives on retailers, specialty chains, and country-specific specialty brands. In addition to this, we performed specific investigations of RC brands owned by A brands, specialty brands, RC private labels, and specialized retailers.

Consumer Survey. Our survey targeted more than 9,000 consumers in nine developed countries. We asked consumers about their buying behavior of RC products, their ideas about and associations with these offerings, their associations with claims and companies, and their trust or distrust of claims and companies.

Within this survey, we executed a conjoint analysis. We monitored 300,000 real-life purchase decisions. All survey respondents were asked six times to identify their preferred option among four RC and conventional products. The products were real brands known in their countries—with a range of prices that were comparable with the price premiums in their countries and with several RC claims. From this exercise, we were able to identify the importance of various claims and the stringency of claims, as well as price sensitivity.

Qualitative Research. We conducted four consumer focus groups—two in Paris and two in Chicago. These groups were executed as MindDiscovery sessions—an approach devised by BCG and its Center for Consumer and Customer Insight—to identify underlying associations and preferences. Working with these groups, we have been able to perform in-depth investigations into consumers’ positive and negative associations with the various types of RC products and the companies offering them. We have also gained further understanding of the occasional distrust associated with these products.

These multiple layers of study confirmed the growing importance of RC products—and pointed us to interesting variations across categories and claims.

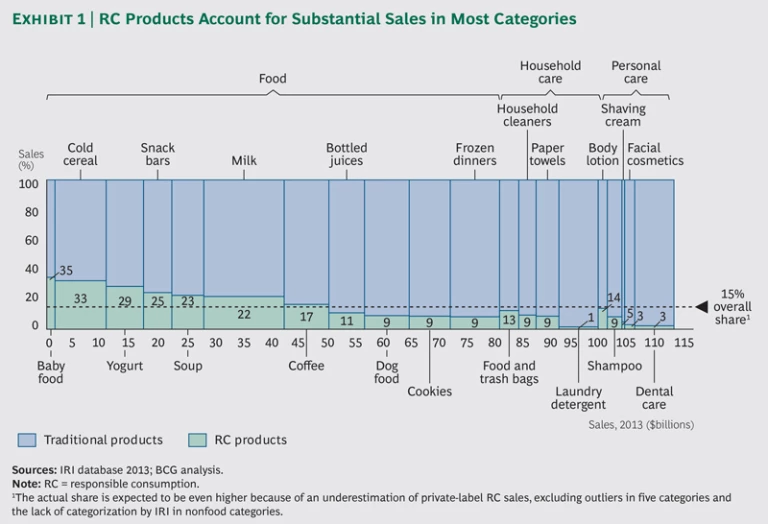

How did these products do? Sales varied across categories—ranging from 30 to 35 percent in yogurt, cold cereal, and baby food categories to negligible levels for categories in which RC products are only just getting started, such as dental care. Altogether, RC products generated $17 billion in sales, or about 15 percent of the total spending of $113 billion in these 20 product categories. These categories accounted, in turn, for 15 percent of consumer sales. We can add an estimated 1.5 percent of total grocery sales from RC chains such as Whole Foods Market and The Fresh Market. These sales, which are not included in the IRI database, are nearly all from RC products. (See Exhibit 1.)

Assuming that similar percentages apply to the overall $738 billion U.S. grocery market, we estimate that $120 billion was spent in 2013 on RC products. Since our consumer surveys, as well as fragmentary research on sales, have shown a similar proclivity in other affluent countries, we can extrapolate beyond the U.S. Total current annual grocery sales for RC products amounts to a staggering $400 billion, or €290 billion. Consumers are not only telling us they spend responsibly. They are actually doing it. (See “What Drives Responsible-Consumption Purchases?”)

WHAT DRIVES RESPONSIBLE-CONSUMPTION PURCHASES?

Understanding consumer motivation is always difficult, especially for products that consumers themselves don’t seem to fully understand. Yet the data has been striking. The 9,000 consumers surveyed in our research generally felt RC claims were just as important as price and brand. All had to choose in a given category among products from different brands with varying price points. Consumers are often willing to pay a substantial price premium and abandon their favorite brands in order to satisfy RC concerns—a fact reinforced by IRI data on actual sales. Why is this happening, especially in the recent troubling economic times?

Idealists may point to altruism, while skeptics focus on selfish motives. Both are wrong. Only 4 percent of consumers in our surveys said that they buy for purely altruistic reasons such as protecting the environment or improving working conditions. And only 9 percent focus on selfish reasons such as safeguarding individual health. Instead, both of these motivations working together have propelled growth in this area—heightened by anxieties driven by news reports of chemical and other dangers. People want products to be “good for me and good for the world.”

RC products bring important emotional benefits at a time of heightened economic and environmental worries. Climate change, food safety scandals, and the growing publicity of health hazards are leaving consumers anxious. They welcome RC offerings in order to gain the feeling of doing something new, different, and right. Specialty brands, in particular, have benefited from this dynamic, but A brands have an opportunity to combine a credible RC claim with the power of their established brand reputation.

While it’s hard to see direct evidence, RC products may also benefit from a class dynamic. Consumer demand is skewing away from mass brands as anxious middle-class people buy affordable luxuries in order to reinforce their status. RC products, with their higher prices and superior packaging, can serve as a new kind of conspicuous consumption. The U.S.-based specialty retailer Whole Foods Market, for example, is not just the biggest provider of these types of products. The company also invests in a more pleasant and comfortable shopping experience—even if doing so requires more packaging and energy consumption. The clean, appealing presentation in the stores also helps overcome any lingering quality concerns. The result has been spectacular growth in the past decade, even during the recent recession.

These factors confirm that RC products have moved firmly beyond their roots in bare-bones specialty shops. Manufacturers and retailers that look for continued growth will want to capture all these dynamics in their offerings.

A Rare Source of Profitable Growth

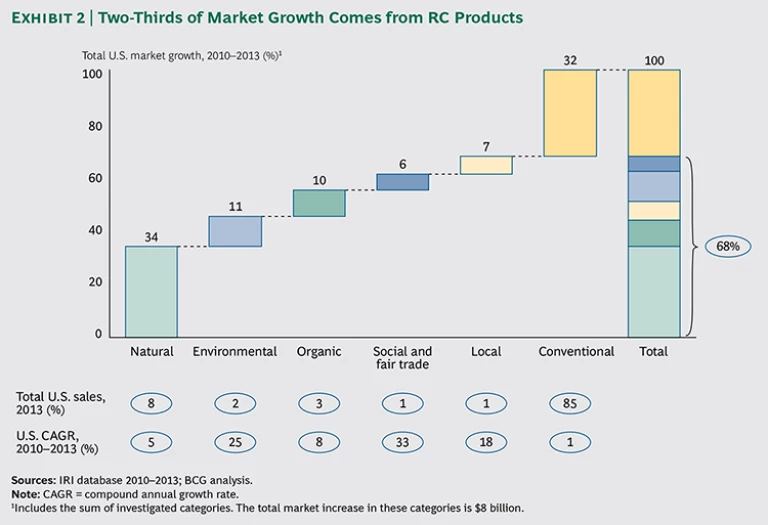

Grocery sales have shown only marginal growth in recent years. Some categories grow, some shrink—but double-digit increases are hard to find. Combine that sluggishness with pressures from private labels, and most consumer-goods companies are struggling to grow. By contrast, RC sales grew at about 9 percent annually even in recent years, rising by $25 billion in the past three years in the U.S. Based on these trends, we expect RC products in the next five years to account for 70 percent of total grocery-sales growth in Europe and the U.S. (See Exhibit 2.)

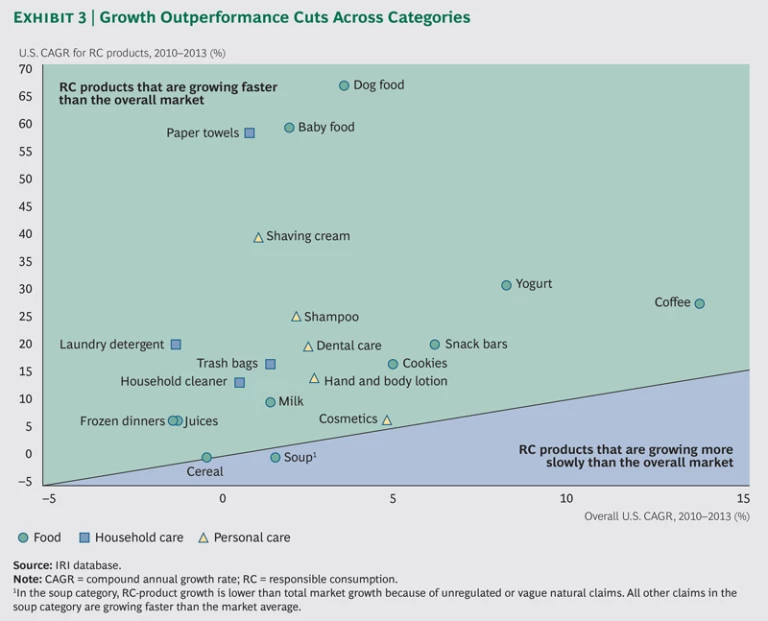

It is not surprising that growth varies across categories. Food has long dominated the RC portfolio, but in the past three years personal care and household care together contributed more to total growth. As for the kinds of claims, some categories emphasize organic; others, natural or ecological; and others, fair or local. The same category can even feature different dominant claims from country to country. But in general, natural, organic, and ecological products—having been around for a while—show annual increases in the 5 to 15 percent range. The newer claims for fair and local products have higher rates. Yet even food products with the most mature claims are still growing well above the grocery average. (See Exhibit 3.)

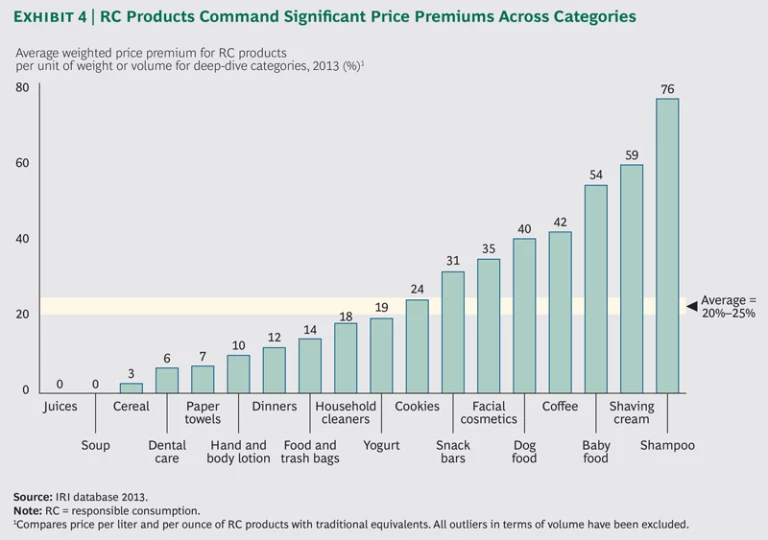

As befits a growing market, RC products also draw a significant price premium. Overall like-for-like price comparisons are not available, but we can work from large samples and analyze prices by weight or volume. We used IRI data to compare the realized price per unit for RC products in the U.S. with those for conventional products in the category. On average, consumers in the U.S. pay 20 to 25 percent more per unit for RC products. Categories vary widely, but 80 percent of the categories have premiums of 15 to 70 percent. (See Exhibit 4.)

We see the same phenomenon when we examine specific categories in the U.S. and European markets. Raw materials are more expensive for RC products than for conventional products, but RC products command substantially higher prices that more than compensate for those higher costs—so they deliver higher margins. When RC products are sold in specialty retailers, or in special sections of a store, margins are usually even higher because the lower-priced conventional items are not adjacent.

Although the price premium will likely shrink over time—at least for existing RC claims—growth will bring economies of scale that can keep margins strong. E-commerce grocery sales are growing overall, but easy price comparisons may put some pressure on RC-product margins. Nonetheless, the Web offers new opportunities. The lack of a physical space constraint allows greater access to niche products online—and many more SKUs than in brick-and-mortar stores. It is also easier to promote RC claims online through rich content and links to partner sites, which can fuel greater demand for RC products generally.

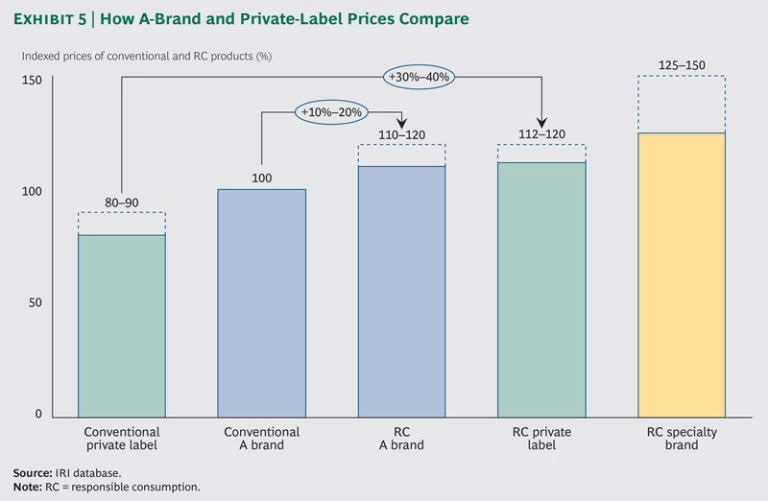

The branding dynamics for RC products are especially notable. Specialized brands have used RC claims to establish a position at the top end of the market—with prices more than 20 percent higher than the leading conventional brands, or A brands. Most A brands have held off from also offering RC products, but those that offer them have priced them at a 10 to 20 percent premium over their regular offering. They’re reluctant to go higher, because they typically set lower price premiums for line extensions compared with their dedicated A brands. Sensing the gap in the market, many retailers are establishing special RC private labels, priced 30 to 40 percent above their regular private-label products (up to 50 percent in some countries)—and often even higher than the flagship A brand. At this price point, RC products provide a major source of margin growth for retailers. (See Exhibit 5.)

Building Trust with Consumers

The growth of RC products continued through the global recession—even with high price premiums. Consumers are not compromising on their RC concerns to save on price. Nor are they willing to accept lesser quality for a lower price. The consumers who are so devoted to these kinds of products that they are willing to accept blemished food, lower standards of personal care, and more household grime are—and will remain—part of a very small group.

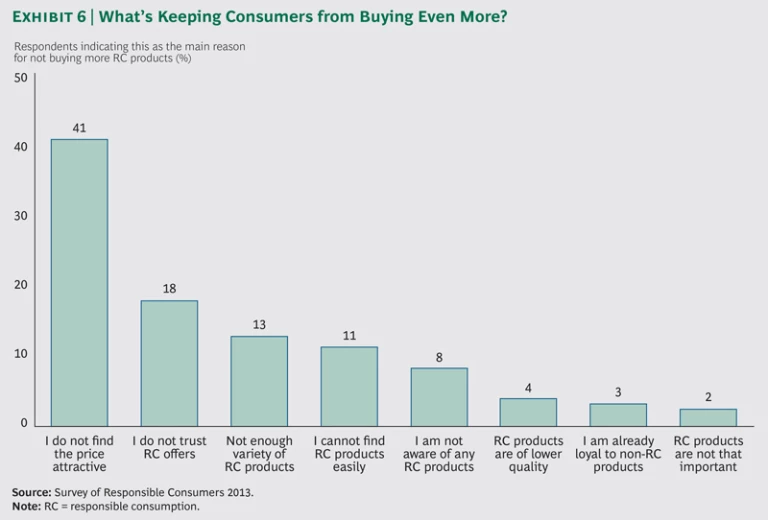

Nevertheless, our surveys suggest that there is rising consumer skepticism about RC-product claims. Many consumers have only minimal understanding of the burgeoning claims and their relevance. Our interactions with consumers have led us to conclude that most find these claims to be fairly interchangeable, and the labels boil down to a general “does no harm.” But the proliferation of claims has consumers confused.

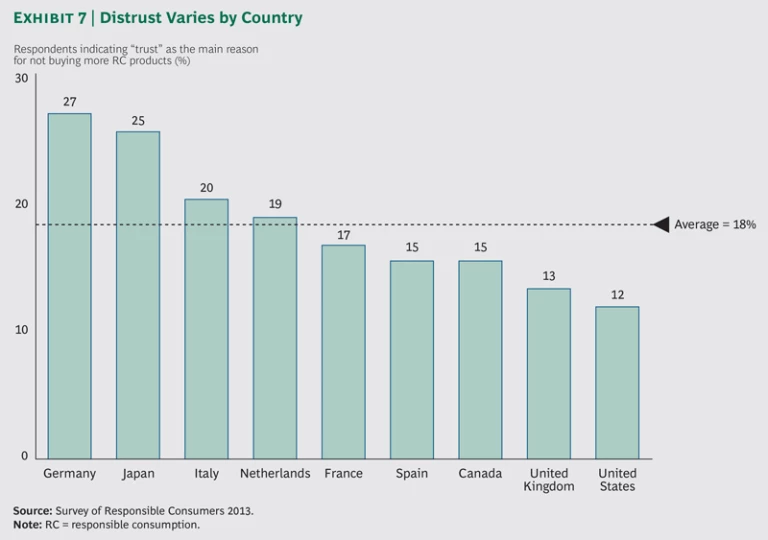

This confusion is combined with low trust in the companies selling the products. After higher prices, lack of trust is the main reason why otherwise sympathetic consumers do not buy RC products more often. (See Exhibit 6.) This is particularly true in Germany, Japan, Italy, and the Netherlands, while it is less of an issue in the U.S. and the UK. (See Exhibit 7.)

Consumers are especially skeptical of A-brand manufacturers’ ability to deliver on RC product claims. Conventional retailers draw only a little more confidence, but they’ve captured strong sales in RC private labels by moving aggressively to meet the demand. Only specialty producers and retailers do reasonably well on trust.

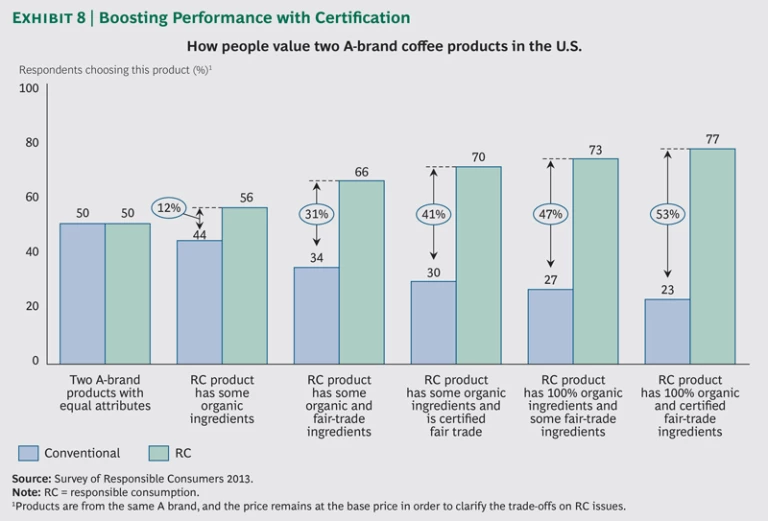

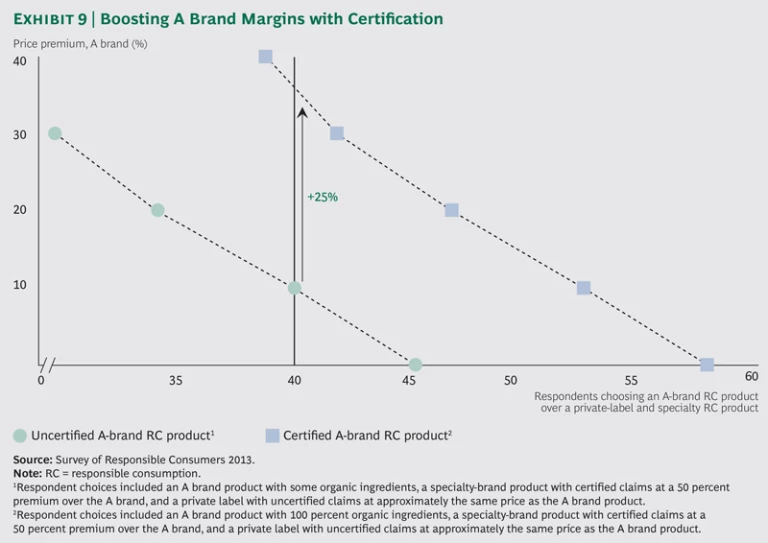

This rising skepticism explains why we see—both in the attitudinal surveys and in sales trends—that consumers are relying increasingly on external validation by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and other bodies. RC products with more stringent and validated claims have seen sales grow, whereas those with vague or nonvalidated promises are falling behind. Consumers are shifting their spending to those products whose claims they trust most. Our analysis suggests not only higher growth but also an opportunity to extract higher price premiums for certified products without losing market share. (See Exhibit 8 and Exhibit 9.)

A Wake-Up Call for A Brands

Not only are a brands underrepresented among RC products but—when they do compete—they are outmaneuvered by private labels as well as specialty brands. In the segments of organic and natural claims, A brands are growing at only 1.3 percent annually, while private labels are reaching 4.3 percent and specialty brands 12.5 percent.

Any lack of involvement will be costly. These manufacturers are missing out on most of the growth from RC products, and, at the same time, their most trusted A brands will directly suffer as other companies’ RC products thrive. Our research suggests that if A brands don’t come forward with credible offerings in this area, one-third of their existing consumers will switch to RC private labels or specialty brands.

Even if A brands decide to ignore the RC market, they will likely be affected over time. As responsible offerings in a category increase, the entire category feels pressure to move toward that standard—as we’ve seen with the success of sustainable fish, fair-trade coffee, and trans-fat-free buttery spreads. The loss of market share would force A brands to fall in line.

In categories in which product quality is a major concern, A brands do have advantages. RC products are capturing less than half of the recent growth in coffee and cosmetics, for example, rendering the threat not as great. (See “Quality Still Dominates: Coffee.”)

QUALITY STILL DOMINATES: COFFEE

With unusually strong consumer engagement, the $8 billion coffee market has long differed from most grocery categories. Quality is a major driver of purchases, so brands have been unusually strong—both A brands and some local brands that develop sizable followings. At the same time, RC claims came to coffee relatively early, especially for fair-trade and other social concerns. Most of the beans came from fragmented small farmers, and consumers were willing to pay a high premium to give them a better deal.

Consumer surveys show that brand loyalty is one reason consumers strongly prefer that A brands—and not specialty brands or private labels—deliver RC products. RC products are growing at 27 percent annually—yet conventional products are still strong, with 14 percent increases per year. If A brands—such as Starbucks—have credible RC claims, they can price their offerings at a markup of 34 percent or more over conventional rivals. Indeed, it was the A brands, more than specialty rivals, that brought RC coffee out of its long-standing niche status.

Consumer tendencies do vary by country. In the Netherlands, organic and fair-trade claims have become the norm for coffee in the past few years, often supported by strict external validation. The U.S. is still far from this kind of acceptance. But in most countries, RC coffee products have already given the category new pockets of value-added differentiation, and they continue to inject dynamism.

Even when RC concerns are growing in these categories, however, consumers may still prefer RC A brands over specialty or private labels. (See “Opportunity in an Otherwise Mature Category: Household Cleaners.”)

OPPORTUNITY IN AN OTHERWISE MATURE CATEGORY: HOUSEHOLD CLEANERS

The household cleaner category may seem stagnant—with less than 1 percent annual growth. RC products came only recently to the category and still make up only 9 percent of its $3.1 billion in sales. But if we de-average the sales, we find that RC products are growing at 13 percent—which means sales of conventional products are actually declining by 0.6 percent.

Consumers told us that they are actively worried about the chemicals in conventional cleaners, both for the environment and for their family’s health. This was especially marked in France—less so in the U.S. Yet consumers in both countries were also concerned about the effectiveness of these products, as the only things worse than these chemicals are the dirt and germs they attack. As a result, few RC products have been able to command a significant price premium. In the U.S., most of the higher-priced RC products come from A brands that start with a reputation for quality and not from specialty makers or private labels; the reverse is true in France.

This need for efficacy and responsibility has given an opening to savvy A brands. By adding regulated claims about the environment, they’ve created new brands with sizable margins as well as growth potential. Clorox’s Green Works, for example, has now reached half the sales of its Formula 409 A brand—and at a higher price point. But speciality brands, such as Simple Green and Seventh Generation, have also made inroads by improving their quality.

Overall potential, however, is still limited by category dynamics. Household cleaners make up a low-engagement group that suffers from commoditization. Even with emotional appeals to health, consumers won’t support margins as large as we’ve seen in coffee.

In fast-moving consumer goods, A brands bring large-scale advantages in raw-material sourcing, manufacturing, and regional reach. Why can’t they leverage these assets to build strong positions with RC products as they have with conventional products? The problem is that most A brand executives continue to see RC products as a niche. When they go after this demand, they prefer to create line extensions under the umbrella of established brands. They’re reluctant to set up strong, dedicated brands that might reflect poorly on the established A brand. But as extensions, these products seem like cautious offerings and tend to offer vague RC claims with little validation—and they fail to win over skeptical consumers. (See “Combining Quality and Responsibility: Hand and Body Lotion.”)

COMBINING QUALITY AND RESPONSIBILITY: HAND AND BODY LOTION

While not as fast-growing as coffee, the $2 billion hand- and body-lotion category still shows the importance of quality. Sales are rising by 3 percent annually—60 percent of which is captured by RC products. Those products already have a market share of 14 percent and are growing at 14 percent annually.

Nevertheless, only half of consumers say that they systematically or sometimes buy RC products in this category. Most such products are not sold at higher prices than conventional versions, so profitability may be limited here. That’s probably because the main claim is “natural,” which in most countries has little or no regulation behind it. Another contributing factor to slow growth may be concerns about quality. In the closely related cosmetics category, in which quality is a major concern, RC products have accounted for very little of the 5 percent annual growth.

As with coffee, A brands may have an opportunity here. They need to dig deeper than weak natural claims to understand what responsible consumption could mean in this category. If they can develop strict certification standards for their formulations—and still draw on their reputation for quality—they will be able to beat specialty brands and private labels and attract substantial margins.

Private labels offer the most worrisome competition to A brands, because retailers can award their own products preferential placement. As the grocery industry consolidates around a few giant retailers, Tesco, Kroger, and other leaders have set up RC labels to compete head on with A brands for affiliation and loyalty. These lines have already eaten into the A brand market share of conventional products by developing some of the same quality propositions as A brands—which enables them to address both mass and niche needs. Historically, A brands have had a strong line of defense in offering richer emotional benefits, whereas private labels have focused on functional benefits. RC products are giving retailers the opportunity to breach this line of defense and connect with their consumers on an emotional level.

Most of these labels, such as Carrefour Bio and Wal-Mart Wild Oats, have focused on a single claim—organic—and applied it to several categories. But now some retailers, such as Ahold’s Albert Heijn in the Netherlands, with its Puur & Eerlijk, “pure and fair,” product line, are gaining additional scale by creating RC sub-brands that cover multiple claims across most grocery categories. Yet those broad product lines incur the added burden of creating credibility for an unknown umbrella brand—as well as managing whatever negative RC baggage the retailer’s brand might carry, as in the case of Wal-Mart’s labor issues.

Getting It Right

If simple RC-product extensions rarely work for A brands, what does? Perhaps the most effective approach is to follow the lead of pure-play specialty brands, such as Tom’s of Maine. Many of these leaders—with offerings that cost considerably more than A brands—have gained a loyal consumer base. But rather than set up a rival offering, A brand manufacturers can simply acquire the specialty brand—as Danone did with Stonyfield Farm.

This strategy works when the acquirer applies its distribution capabilities and extensive reach in order to accelerate growth—but otherwise grants the specialty brand wide autonomy. The brand remains distinct in the marketplace and maintains its credibility and authenticity, escaping the distrust consumers often feel in the large corporation behind the acquiring A brand. Many buyers may not even be aware that ice cream maker Ben & Jerry’s is now owned by Unilever or that Cascadian Farm’s organic products come from General Mills.

If a good specialty brand isn’t available, an A brand can make its own—and keep it separate from the main brand umbrella. Clorox’s Green Works line of household cleaners is independent of its Formula 409, Pine-Sol, and other A brands in the same category. More important, the U.S. government certified that the entire Green Works line met safety criteria for the environment and human health.

A few A-brand category leaders have gone a step further in following the lead of specialty brands. They have fully embraced specific responsible claims and adopted them across their portfolios. Doing so turns the claim into a new category standard or a major contributor to an A brand’s overall differentiation. So far, we’ve seen this mainly with fair-trade coffee, especially with Starbucks worldwide. Embracing the fair-trade claim has enriched Starbucks’s own value propositions—and blunted the challenge from pure-play RC brands. The company has also raised the bar—and the cost of doing business—for smaller competitors and conventional private labels.

How You Can Benefit

The rc market is a large, high-growth, high-price, high-margin market—and it is dynamic. Consumers are willing to buy even more, but they are often confused about the claims, lack trust in the products, and seek guidance. Today, A brand manufacturers and retailers have an opportunity—and governments and NGOs can step in to encourage the market. Entrepreneurs and investors sensing the growth possibilities can adapt our recommendations to fit their goals.

Manufacturers. Manufacturers of A brands have to decide how they will benefit from or defend themselves against this trend. Inaction is a recipe for gradual decline. There are four basic steps manufacturers can take to arrive at a winning strategy that can fit their category and starting position:

- Get the facts. Understand today’s demand and the current product offerings—not just RC claims but also price points and volume. Assess category-specific consumer attitudes and the credibility of your own and competing brands—including private labels—in order to deliver the relevant claims.

- Pinpoint the opportunity space. Identify the unmet needs. Is a given claim underrepresented in a certain category? Or do brands already compete with that claim, but with weak validation? From there, prioritize the opportunities based on size and feasibility and select the appropriate strategy: acquisition of a specialty brand or transformation of the A brand around the specific claim. If your specific context justifies it, you can also consider a carefully established flanking brand that is developed internally but with external validation. (For more on this course, see “Partners for Trust.”)

PARTNERS FOR TRUST

Because of past successes, A brands are at a distinct disadvantage in competing in RC markets. Consumers point to the A brand as just the kind of conventional product to move away from. Manufacturers of A brands have built up such strong roots in the old way of doing business that consumers are skeptical that they can shift to the new RC approach.

Yet many of the RC claims are not as difficult to meet as industry critics might suggest. The very progress of these products up to now has greatly improved the quality and feasibility of natural, organic, fair-trade, and social goods. Manufacturers of A brands can draw on all of the industry’s improvements and scale up their investments. Major moves from such conventional players as McDonald’s, Unilever, and Wal-Mart are further transforming value chains toward RC goals.

Once an A brand has determined that meeting an RC claim is feasible—either by embracing it across the portfolio or within a focused product or brand extension—it needs to find outside validation in order to clear the credibility hurdle. Often the best way to do that is through a nongovernmental organization.

With rising concerns about the future of once-abundant aquatic life, StarKist and other A brands have promoted a variety of externally certified measures of responsible practice. In collaboration with the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation and other NGOs, these brands have developed “dolphin safe” and other markers for their products.

- Plot the course. Lay out the brand, proposition, overall portfolio, product requirements, external validation, partners, and business case to succeed.

- Define the end-to-end agenda for the value chain. Chart the practical implications for branding, sourcing, manufacturing, marketing, distribution, and sales.

Retailers. Now is the time for retailers to boost their overall brand image and play at price points that are normally reserved for A brands. They should do the following:

- Get the facts. Understand today’s demand and offerings, including claims, price points, and volume. Assess category-specific consumer attitudes in the most promising categories, as well as the credibility of your current private-label and manufacturer brands in delivering on the relevant claims.

- Identify the opportunity space. Understand the categories with the highest unmet need and lowest level of competition from specialty and A brands—and settle on the targets.

- Choose the cross-category strategy. Evaluate the potential for a dedicated RC private label and its most viable claim or umbrella positioning.

- Define the end-to-end agenda for the value chain. Decide on the required portfolio and strategy for launching the product—and how to meet product requirements. Work through the implications for sourcing and partnering, and seek the external validation and resulting business case to succeed.

Nongovernmental Organizations. Groups such as the World Wildlife Fund (in nature conservation and sustainability) and Fair Trade USA (in social-commodity production) have been pushing for market-driven change for a long time. Consumers are now responding, but the job of NGOs is not done. If they and others, such as government leaders, would like to accelerate RC consumption, they have a few levers:

- They can reduce consumer confusion by bringing more transparency to production standards and the impact that products might have. Their efforts can focus consumers on product characteristics that have the greatest impact on society.

- Likewise, they can promote trust by providing external validation—including certification—to products that meet the most stringent standards. They would thereby encourage RC leaders to capture the rewards of their leadership.

- They can work informally to persuade manufacturers of A brands and other product leaders to make relevant responsible claims the standard in a product category. They can help show that improved product performance is not only possible but also commercially attractive. As the number of RC products increases, competition increases, prices go down, and sales climb.

Companies in the overall grocery sector have a major opportunity in the next several years. A market segment that has already reached $400 billion will likely grow by an additional $180 billion. Realizing this opportunity will not be easy, but companies that succeed will do well and do good.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the project team—Caroline Wilschut and Silvio Erkens—for rigorously analyzing the IRI database, consumer survey results, and MindDiscovery workshops, resulting in the insights of this report.

We extend special appreciation to our partners at IRI, whose collaboration made this research possible.

We would also like to thank John Landry for his help in writing this report, as well as Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Sarah Davis, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, and Sara Strassenreiter for their contributions to its editing, design, and production.