There are three truths about revenue growth. Over time, it is imperative. Across all industries, it is possible. And experience shows that it is perilous.

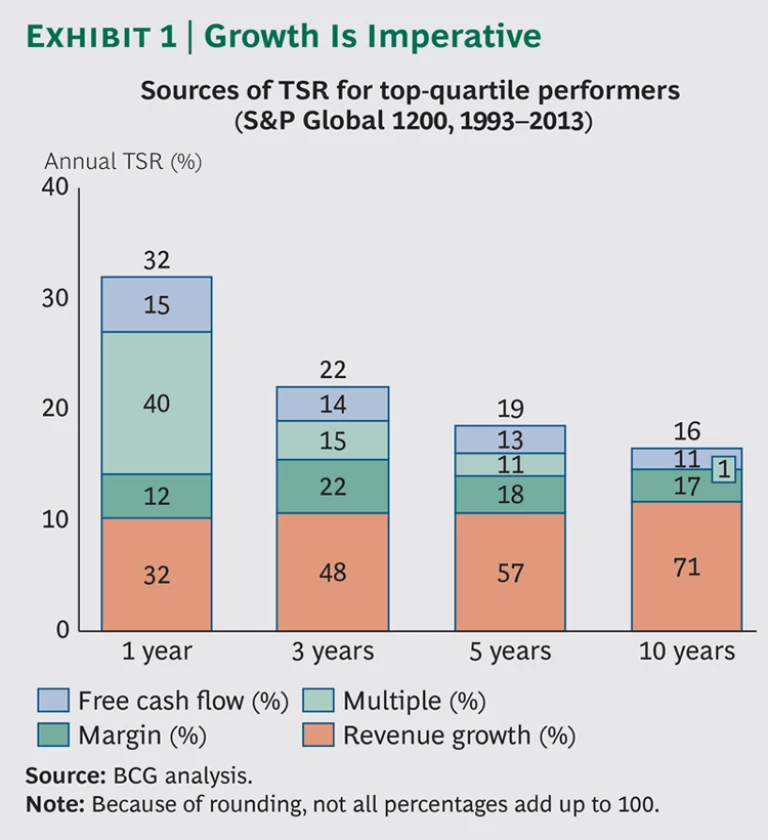

Growth is imperative because it strengthens companies and drives the capital gains they deliver to shareholders. It builds advantages of scale and scope, attracts talent, delivers funds for reinvestment, and forces competitor investment. Studying the top-quartile value creators in the S&P Global 1200 from 1993 through 2013 is revealing. Even in the short term, revenue growth accounted for 32 percent of one-year total shareholder return—more than twice the contribution of increased free cash flow and nearly triple that of margin expansion. And in the long term, revenue growth was nearly all that mattered, explaining 71 percent of ten-year TSR. (See Exhibit 1.)

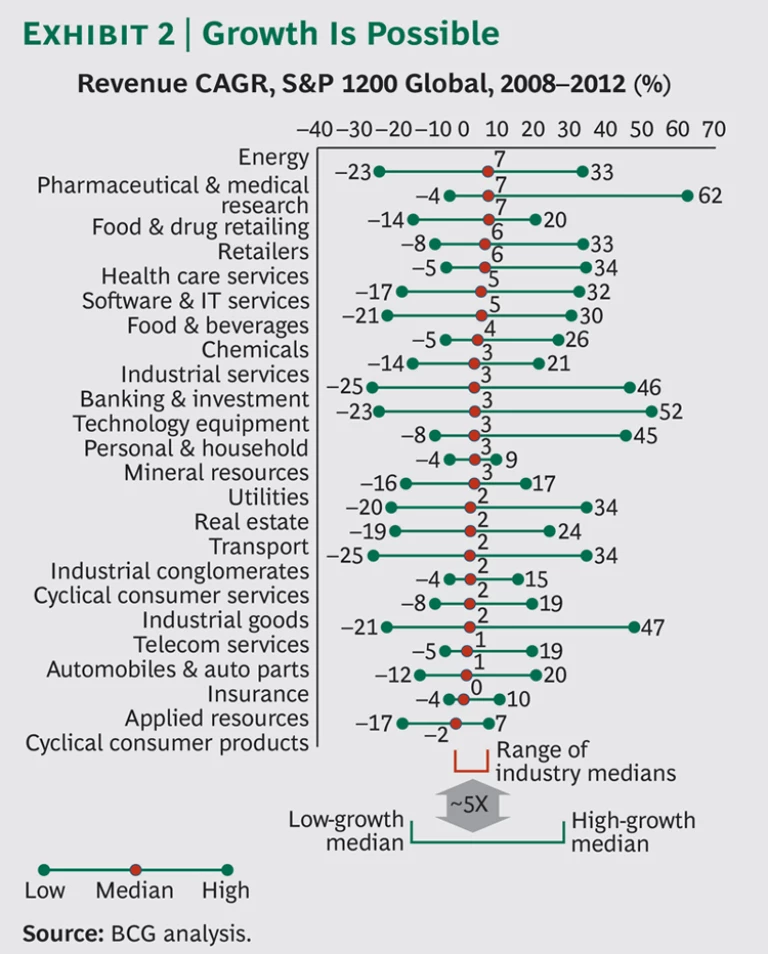

Many executives, sobered by growth headwinds or past failures, consider growth a long shot. However, our analysis shows that growth is possible even in the most challenging sectors. On average, there is five times greater variability in growth rates within an industry than there is across industries. It is not the cards you are dealt; it is how you play them. (See Exhibit 2.)

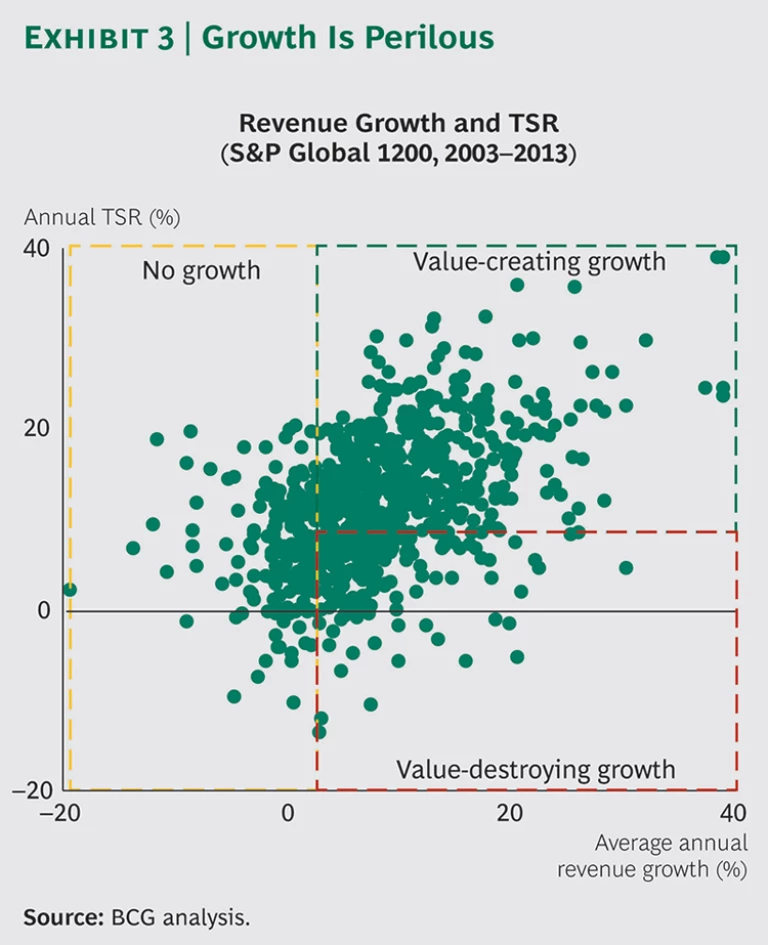

But not all growth is good growth—and the path is perilous. Just one-third of the full S&P Global 1200 achieved value-creating growth between 2003 and 2013. Another third failed to grow at all. And the final third grew, but destroyed value in the attempt. (See Exhibit 3.)

As growth itself is perilous, so is any attempt to distill an easy formula for its success. Our research into valuable growers shows a startling variety in growth paths, in strategic choices, and in the shape of growth investment. A closer look, however, reveals patterns. First, among the heterogeneity of growth strategies, we found three archetypes that tend to be successful. These were linked, importantly, to a company’s starting position. Second, while we saw great variety in these strategies (the what of growth), there was consistency in the disciplines followed by those companies that delivered it (the how of growth).

Choosing a Growth Path

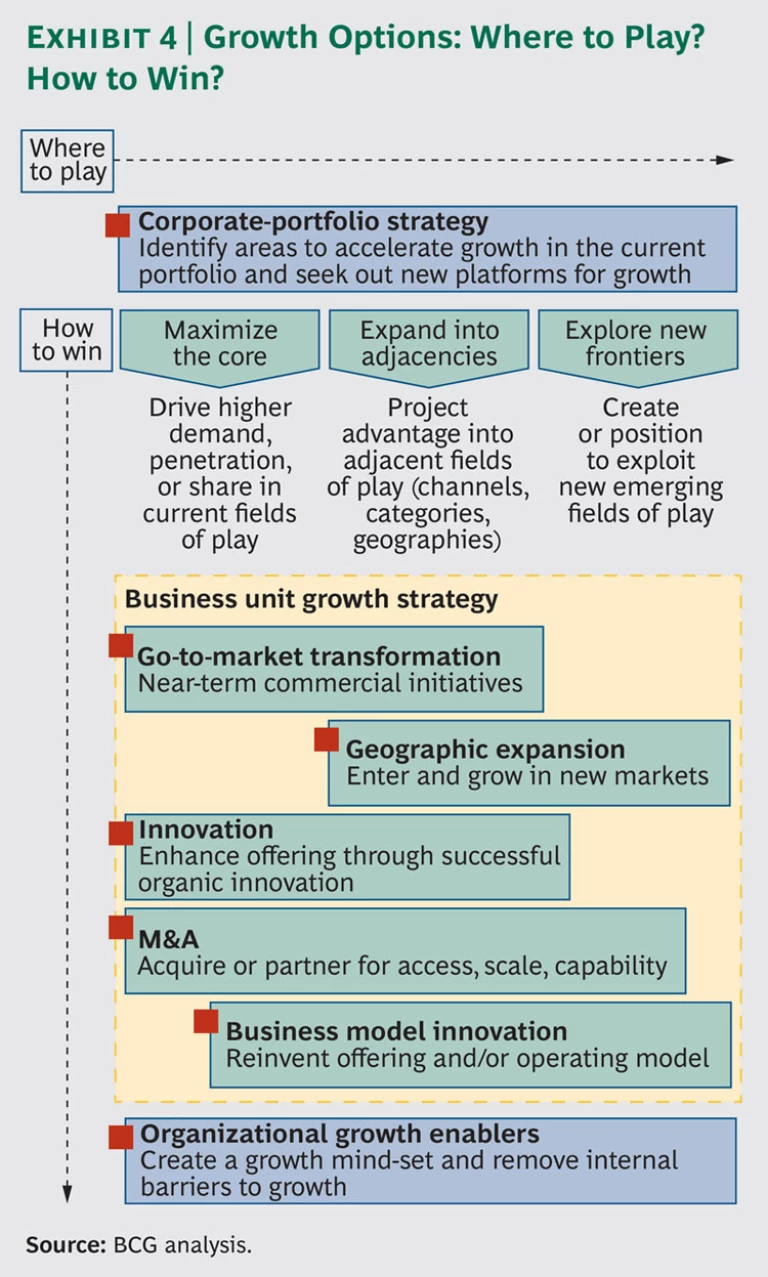

The what of growth can be summarized as a cohesive set of decisions about where to play and how to win. Deciding where to play means allocating bets and resources across the core, adjacencies, and new frontiers. Core bets involve finding headroom in market share or customer demand within the current footprint of the business. Adjacency bets extend current advantage into nearby offerings, channels, or geographies. New-frontier bets are longer throws that more dramatically reimagine offerings or business models—or find new uses for old assets. These choices determine the field of play but once made, require additional choices about where a business will invest to win on the field. We suggest seven how-to-win levers that can be differentially employed for success.

- Corporate-Portfolio Repositioning. For multibusiness companies, which businesses and geographies have the greatest value-creating growth potential, and which the least? What are the implications for investment allocation, key performance indicators, and divestment?

- Go-to-Market Transformation. What opportunities exist to drive growth through changes in marketing and sales strategies? How can we embrace radical changes in customers’ purchasing pathways and leverage tools such as digital marketing and big-data analytics?

- Geographic Expansion. Which new markets offer the best growth prospects? For developed-world companies, which emerging markets offer the most potential and what moves are required to achieve market leadership? For developing-world companies, how to prioritize expansion opportunities beyond the home market?

- Innovation. What is the right investment mix between enhancements and extensions to existing products and services, on the one hand, and new and new-to-the-world products and services, on the other?

- Mergers and Acquisitions. Can we accelerate our penetration into new geographic markets or market segments and our access to critical technologies or capabilities, and can we travel faster down the scale curve by buying rather than building in-house?

- Business Model Innovation. What changes are needed to access attractive opportunities that lie outside the economic reach of the current business model?

- Organizational Moves. What approaches to leadership, culture, talent management, and capability development are best suited to support the chosen growth strategy? Are these supported by the current organization design?

Exhibit 4 illustrates the interrelationships among the various strategic choices at the heart of growth strategies. Limited resources (and good sense) argue against investing everywhere. Valuable growers make decisive choices, but the choices differ. So how is the right path to be discovered?

Starting Point Matters

We studied 1,600 companies to bring some evidence to bear on the question. Of these, we selected for companies that first experienced a period of stagnant growth but then rallied to deliver a rate of revenue growth that was at least two times that of their peers for a period of more than five years. These “uphill growers” (of which there were only 310) provided a critical insight: starting position matters. A company’s starting position influences the probability that a dollar invested in growth will deliver shareholder return. And it also suggests preferred investment patterns across the “where to play, how to win” field.

We define starting position along two dimensions. The first is competitive premium: Does the company command a gross-margin advantage over its rivals? The second is competitive stability: Is the business characterized by equilibrium (relatively steady market shares, stable demand, or high entry barriers) or by turbulence (competitive churn, disruptive technologies, or fast-changing consumer behavior)?

Our research revealed three archetypal starting positions, described below, that suggest distinct pathways to value-creating growth.

Fortress. Companies in stable markets with a strong competitive premium occupy this position. For them, winning growth strategies typically involve reinforcing and extending the advantaged core. The investment focus is on both strengthening the core premium and expanding into close adjacencies. Go-to-market transformation, geographic expansion, innovation, and M&A are the most common levers. This is the path Procter & Gamble followed in the first decade of the 2000s. First it retuned its portfolio—divesting many noncore food and beverage brands. It then captured growth through attractive adjacencies, notably the Gillette acquisition, and through organic innovation in new categories and new brands, like Swiffer and Febreze.

Fading. Companies in stable markets with a low competitive premium fall into this category. Their path to value-creating growth commonly calls for more dramatic action, rebalancing the portfolio through disinvestment or divestiture and pursuing more distant adjacencies. In this case, the dominant growth levers are portfolio optimization, innovation, and M&A. Britain’s Daily Mail, facing declining print-advertising spending, stabilized the core and freed up cash for growth investments through operational initiatives and the sale of noncore assets. It then made decisive investments in digital capabilities and launched Mail Online, today the top global newspaper site, generating revenues that more than compensate for the decline of print.

Fluid. These companies operate in turbulent, unstable markets. Breakout growers often choose multiple options for growth by placing their bets across the core, adjacencies, and new frontiers. This positions them to rapidly adapt to and exploit changes in the market landscape. Success comes not from prescience but from agility. Innovation and acquisitions are the primary levers for growth. Fashion is a fluid sector, and in the early 1990s, Hugo Boss found its traditional focus on expensive men’s suits to be increasingly off-trend with the rise of business casual. The company reignited growth through a series of bets outside its traditional core, making investments in women’s wear, kid’s wear, sports clothing, even home goods—as well as in new channels.

Embarking on the Growth Journey

While our uphill growers were diverse in their starting positions and strategic choices, they followed common disciplines to achieve valuable growth. Among our clients, we have found these lessons on the how of growth to apply nearly universally:

- The nature, number, and risk profile of growth initiatives cannot be set without a clear view of the gap to be closed. The start of any successful growth strategy requires an honest and rigorous assessment of the growth of all current initiatives, a clear and shared upside growth objective, and quantification of the gap between them over the plan horizon.

- The effort spent looking outward at the marketplace must be matched by the effort spent looking inward at a company’s unique advantages and capabilities. Hidden advantage can be missed. Known advantage may be overstated relative to traditional or maverick competitors. And today’s advantage can be rendered obsolete or even become a liability as consumers, customers, and industries change.

- To best leverage their advantage, companies must stretch their thinking. New perspectives can upend longstanding beliefs about “stagnant cores” or “distant adjacencies.” Often, faint signals lost in the noise of today’s core suggest opportunities. And unattractive adjacencies can become attractive when paired with an acquired capability, or when their collateral value in reinforcing the core is considered.

- For many companies, finding growth ideas is less difficult than focusing on the ones that matter. We like to ask three questions of all growth ideas: What is the size of the prize? What is our right to win? And what is the path to success? A strong business case is built on these three questions, and a strong strategy is built on a cohesive, qualified set of business cases.

Above and across all of these disciplines, one observation recurs among valuable growers: they pursue growth in the right order. They first earn the right to grow through operational efficiencies and the cultivation of advantage in the core business—whether that advantage comes from strong brands, cost control, or better customer insight. And as they pursue growth, they bring the same creativity and discipline to funding that growth through concurrent operational and cost initiatives. Repeatedly, our breakout, value-creating growers demonstrated the ability to hold or expand margins as they grew.

Even when you have a growth strategy that is clear in ambition, creative in ideation, discriminating in investment, and supported with leadership and funding, two hurdles remain.

Internally, the operational effectiveness that earns a company the right to grow can often restrain growth. Strong operators fight waste, avoid uncertainty, concentrate on the near term, and replicate past success. But breakthrough growth frequently requires a tolerance for experimentation and a departure from past playbooks. Shifting to a growth mind-set requires doing some things differently, without degrading the core and its foundational advantages. This balancing act, whether achieved by luck or design, explains the success of most of our breakout growers. Operationally strong incumbents can make moves to redefine their business, create distinct attack structures, and gain needed capabilities through partnerships, new hires, or acquisitions. Better to bet on these than on luck.

Externally, building credibility with investors about growth investments, especially their risk profile and speed of payback, is a critical enabler of breakout growth. Growth strategies require capital and don’t pay off immediately. Successful migration toward an investor base that embraces the growth strategy usually requires a clear medium-term roadmap, several quarters of transparent communication, and “doing what we said we would do.” Most of all, companies need to keep their investor messaging realistic, talking candidly about the drivers of performance and returns.

As with most things worthwhile and difficult, valuable growth has its reward. Organizations are strengthened, share price responds, and a virtuous circle is initiated in which expansion creates fuel for further expansion. Across companies that get there, we see diversity but not randomness. There are patterns of investment keyed to starting position, employment of both short- and long-term growth levers, and equal attention to external change and internal advantage. Players that master these disciplines can, across every industry, grow when the growing gets tough.