Today, with increased marketplace volatility and the rising diversity of attractive customer segments, business models age faster than ever before—making business model innovation an important strategy for driving value-creating growth. It can be deployed to both defend and disrupt: a powerful response to declining competitiveness and a decisive means to seize new opportunities.

But executing business model innovation—the process of changing both the value that is promised to customers and how it is delivered to tap into new profit sources—is certainly more complex than traditional product or service innovation. It’s hardly surprising then that although 94 percent of the 1,500 senior executives surveyed in the 2014 installment of The Boston Consulting Group’s annual research on the most innovative companies reported that their companies had engaged in business model innovation to some degree, only 27 percent said their organizations were actively pursuing it. This is despite the fact that the complexity of the large-scale change effort involved makes it difficult for rivals to imitate, which affords successful innovators with both a longer head start and a more durable competitive advantage.

Companies hoping to drive growth through business model innovation face a number of critical questions: How broad should the scope of the effort be? What is the appropriate level of risk to take? Is it a onetime exercise, or does it call for an ongoing capability? How can a company discern which new business model is the most attractive? And what differentiates those companies able to transform their business models from those that might run a pilot but fail to fundamentally change the company’s trajectory?

To answer those questions, it is important to realize that not all efforts toward business model innovation are alike. Understanding four distinct approaches can help executives make effective choices in designing the path to growth.

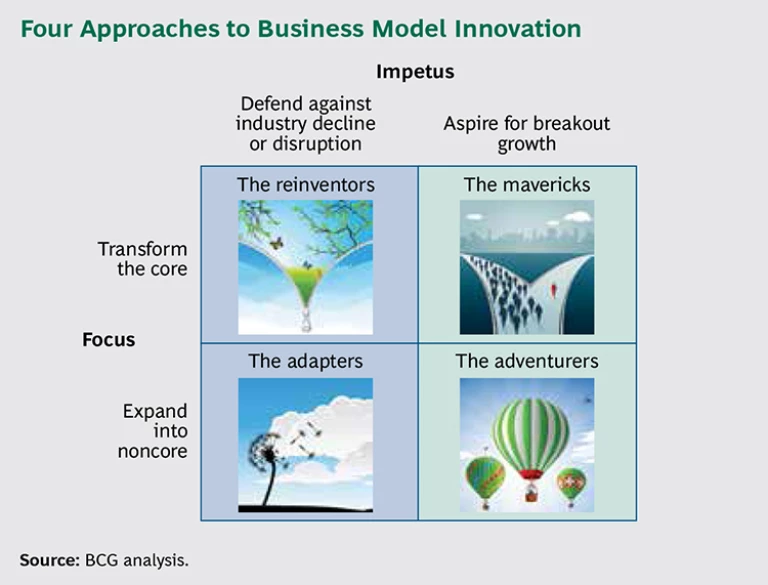

Four Approaches to Business Model Innovation

To understand which business model innovation approach fits best for any individual company, it is critical to understand both impetus and focus. Impetus: Is the company defending against an external threat, such as commoditization, new regulation, or an economic downturn—or is it proactively disrupting the status quo? Focus: What is the most attractive area of opportunity—does it reside in the core business or in adjacent businesses or markets?

These two factors define a matrix of four approaches to business model innovation. (See the exhibit below.) Within each of the four approaches, companies will employ different tactics to successfully rebuild their models and make different choices.

- The reinventor approach is deployed in light of a fundamental industry challenge, such as commoditization or new regulation, in which a business model is deteriorating slowly and growth prospects are uncertain. In this situation, the company must reinvent its customer-value proposition and realign its operations to profitably deliver on the new superior offering.

- The adapter approach is used when the current core business, even if reinvented, is unlikely to combat fundamental disruption. Adapters explore adjacent businesses or markets, in some cases exiting their core business entirely. Adapters must build an innovation engine to persistently drive experimentation to find a successful “new core” space with the right business model.

- The maverick approach deploys business model innovation to scale up a potentially more successful core business. Mavericks—which can be either startups or insurgent established companies—employ their core advantage to revolutionize their industry and set new standards. This requires an ability to continually evolve the competitive edge or advantage of the business to drive growth.

- The adventurer approach aggressively expands the footprint of a business by exploring or venturing into new or adjacent territories. This approach requires an understanding of the company’s competitive advantage and placing careful bets on novel applications of that advantage in order to succeed in new markets.

Business Model Innovation in Action

There is no simple formula for successfully reinventing a company’s business model. Instead, companies within each of these four categories often deploy different tactics. These tactics touch on everything from how to recognize the key opportunity to how to implement the new model and harness the necessary resources. We delve into the stories of four companies, cases that highlight how a different set of moves are required to succeed under each approach.

Reinventor: Schlumberger confronts the changing market for oil and gas. Reinventors respond to intense pressure by rethinking their existing operation. For these companies, there are two key steps to remaking the business model:

- Redefine value for customers. Reinventors do not need to be radical. Rather, they capitalize on their expertise to find ways to reinvent their customer-value proposition to unlock new advantages, such as customer loyalty. Moving from providing commodity products to embedding products in more value-added services is one common pathway.

- Cannibalize proactively. Though the change may not be revolutionary, efforts must be broad-based and fully committed—including a willingness to reinvent every function in the company in order to deliver on a more attractive value proposition to the customer profitably. Reinventors do not deny the decline of the core business. Instead, they figure out how to control and benefit from it—rather than letting rivals set the terms and the pace.

A fundamental shift is occurring in the oil industry: reserves in easy-to-exploit fields are being depleted. And newly discovered reserves frequently sit in deep water or remote locations, requiring complex, costly, and often high-risk projects in order to gain access to them. At the same time, international oil companies are trying to extract as much as possible from existing oil fields, efforts that also come with high costs and significant technical obstacles. For oil services company Schlumberger, the disruption facing its core customers threatened the future growth of its traditional drilling and production-services operation.

There was a major opportunity, however, for Schlumberger to expand the role it played for national oil companies, entities that controlled significant untapped reserves. The company responded by increasing its focus on a different business model within its core, a unit called integrated project management. By collaborating across business lines and contracting for third-party services when needed, integrated project management offers customers a turnkey solution—rather than individual products or services—for increasingly large and complicated projects. And under this model, Schlumberger often assumes some of its clients’ exposure by creating risk-sharing arrangements.

The new model appeals to national oil companies in particular because these companies often lack the expertise and technology to manage large oil projects on their own. In those cases, however, Schlumberger’s integrated project management unit is infringing on the role that major oil companies—also Schlumberger customers—have typically played for national oil companies. The upshot: As Schlumberger’s business expands, it risks alienating a critical customer base within its traditional services business.

Despite that trade-off, Schlumberger pushed aggressively into integrated project management. By 2013, the company was managing 55 projects in more than 40 different countries with revenues from integrated project management growing at an average annual rate of 13 percent from 2002 through the end of 2011.

Adapter: Aon Hewitt responds to health care reform. Adapters focus on finding a way to exploit their core business expertise to break into new markets and businesses. In order to succeed, they must address two issues:

- Find untapped value in current assets and capabilities. Expanding into new markets inevitably requires operating in unknown areas and experimenting. Adapters minimize additional risk by understanding their strengths and moving decisively to apply them in new—and growing—areas.

- Make adversity an advantage. The most attractive opportunities often exist where market disruption or new regulations expose new customer needs. Adapters tap into these.

Aon Hewitt, a global talent, retirement, and health-solutions company, moved on both fronts as it looked for ways to address the transformative changes in the U.S. health care industry. With the rising cost of providing health care and the declining health of U.S. workers, employers were struggling to offer high-quality, affordable health care for employees and their families. They were also paying into a system in which they had no control or influence over the supply and price of services.

Recognizing that new solutions were needed, Aon Hewitt moved to harness its benefits expertise and trusted reputation to build a business in an adjacent space—private health exchanges. And although the company had been working on a private-exchange model for several years, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act accelerated its creation by prompting an increasing number of employers to rethink their role in employee health care. In late 2011, the company was the first to launch a multicarrier, multiemployer private exchange to serve large employers. The aim was to establish private exchanges as an alternative to public exchanges, providing a means for large employers to offer more choice, cap health care costs, and reduce the burden on HR departments. Aon Hewitt CEO Gregory Case went on record to say that the company would spend $100 million over the course of a couple years to build that business.

Aon Hewitt is at the forefront of a potentially significant shift. In 2014, the company conducted a survey of more than 1,200 large employers and found that a full 33 percent expected the private-exchange model to be the preferable approach for offering employee health benefits in three to five years—up from just 5 percent at the time of the survey. And in the fall 2013 benefits-enrollment season, more than 600,000 employees and their family members signed up for health benefits through the Aon Active Health Exchange. Significant uncertainty remains in this segment, including how private exchanges will evolve and just how much share they will garner over the long term. But Aon Hewitt has hedged its position should these mechanisms become a dominant force in the market.

Maverick: Red Hat upends the software business. Mavericks zero in on what established companies often overlook. They commonly leverage two key approaches:

- Target the sleeping giant. Mavericks exploit the complacencies of incumbents—a goal that calls for commitment and grit. Such complacency is often evident in low levels of customer satisfaction or the extent to which customer needs go unmet.

- Minimize the barriers that stand between you and the customer. While mavericks may have a superior offering or technology, the key to turning that advantage into value is often to connect with customers in a new way. This new approach must reduce the risk, inconvenience, or complexity of adopting the maverick’s product or service.

In the case of Red Hat, the sleeping giant was Microsoft. By the late 1990s, Microsoft’s Windows NT was the leading operating system, installed on well over a third of servers shipped each year. NT was stable and reliable, and it worked on a wide range of server hardware—but it was expensive and difficult to customize.

Red Hat sold a version of Linux—a powerful Unix-like open-source operating system developed by a self-organizing global community of programmers. Red Hat’s Linux was being used at nearly all of the Fortune 500 companies—but not on core enterprise applications such as major databases and transaction processing. The software was reliable, efficient, and significantly less expensive than NT, but few of the major enterprise applications offered by companies such as SAP, Oracle, and IBM were certified to run on it. Linux was a community creation, so the code changed frequently and application providers couldn’t certify their programs to work on a moving target.

Red Hat addressed Linux’s shortcomings among large corporate users through business model innovation. It created specific “releases” of the software. Those releases, purchased through a subscription, would remain constant for a predictable period of time so that enterprise users could depend on its stability—and customers would be able to test new versions extensively before deploying them. Linux’s new stability cleared the way for Red Hat to forge partnerships with IBM, Oracle, and SAP, among others. Those companies not only certified their applications to run on Red Hat’s releases but in some cases also sold Red Hat Linux along with their own products.

Supported by this new business model, Red Hat introduced Enterprise Linux in 2002. By 2003, eight of the top ten investment banks used Red Hat Linux for mission-critical applications. And by the end of 2011, Red Hat was the first open-source software company to reach $1 billion in annual sales.

Adventurer: Virgin’s new model powers expansion. For adventurers, a primary challenge is managing the trade-off between innovating and protecting the core business. This implies two imperatives:

- Stabilize the core. Adventurers must be vigilant about ensuring the company preserves a solid financial foundation and protects its resources. Many of these companies use outsourcing or partnering as a way to minimize capital investments and risk.

- Establish a permanent, dedicated innovation team to place bets in new spaces. Innovation for these companies is not a onetime effort. They establish a pipeline to generate new initiatives with well-tested managers at the helm of that effort. In this way, innovation efforts are managed separately from the core business.

Richard Branson is a self-described adventurer, a title that also fits the company he founded. Branson’s Virgin Group has a knack for identifying markets in which leaders have grown complacent and disrupting those markets with a business model that puts a laser focus on customer needs.

Virgin has been able to explore new territory—from financial services to telecommunications to space travel—in great measure because it preserves the strong financial base of its core travel, entertainment, and lifestyle businesses. Branson encourages risk taking while still protecting the company against the downside of those initiatives. This discipline is reflected in the clear financial criteria set for new investments, including a projected internal rate of return of greater than 35 percent for startups and 25 percent for projects requesting follow-on funding.

At the same time, Branson does not leave the identification of opportunities to chance. He leads a senior investment team, comprising highly successful Virgin executives with extensive experience outside the company. This team is tasked with spotting and selecting new investments.

Examining the track record of successful business model innovators reveals that such innovation can be a solution to major challenges and a tool to accelerate growth. To begin to assess whether your best opportunities reside within or adjacent to your core—and whether you will gain more from playing defense in existing markets or going on the offense in new ones—ask yourself the following questions:

- Look beyond your current product or offering. What is the broader problem you are solving for your customers? How would someone else solve it differently? Can you reinvent the value proposition to your current customers?

- Stare oblivion in the face. Is your business in a slow but definite long-term decline or is there a big event that could render your business irrelevant in the not-so-distant future? Even if you best competitors in this situation, would you still fall short of your growth aspirations? What decisive business- model moves might represent an antidote?

- Broaden the ecosystem. Are there “unusual suspects” for partnerships? Could this be a path for entry into adjacent spaces?

- Take a different perspective. How might different mind-sets point you toward different actions? For example, would a private-equity firm get excited about rapidly scaling your business in different or adjacent segments?

Thinking through the options that these questions reveal can help a company focus on the highest-value moves and select the right approach to evolving or remaking the business model. And, in turn, that selected approach and specific opportunity will help inform the breadth, risk profile, and duration of the transformation plan—and whether the company needs to pursue business model innovation on a periodic or a perpetual basis.