Emerging markets are no longer emerging. Many of them have arrived—and they are fueling about two-thirds of global GDP growth. With young populations, growing middle classes, and rising consumption, these markets are becoming more prosperous and, despite recent headlines, more stable. In most of these markets, long-term resilience will trump short-term turbulence.

2014 BCG Global Challengers

Many of the companies in these markets are also growing up rapidly, relying on innovation, talent, and other strengths to win. One example is Mindray Medical International—a Chinese medical-technology provider focusing on patient care and imaging and diagnostic products—which wants to be a force in all major markets and recognizes it must innovate to succeed in them. The company is committed to spending 10 percent of revenues on R&D.

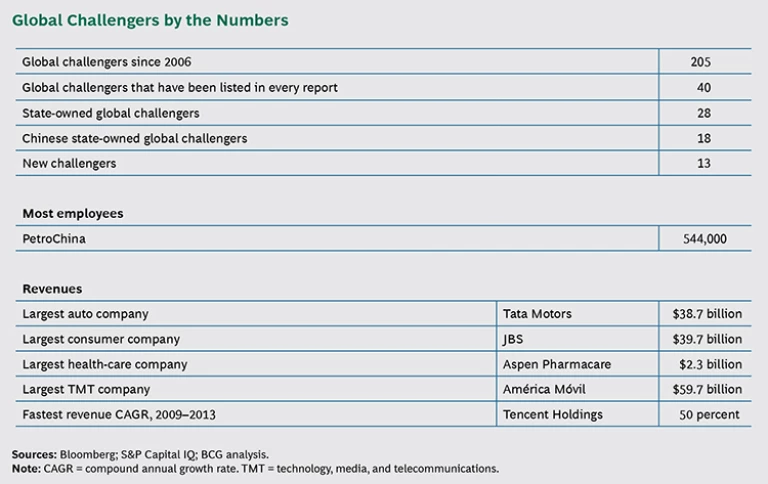

To celebrate the success of these companies, we are publishing a list of 100 rapidly globalizing companies from emerging markets—the 2014 BCG global challengers. This is the sixth time we have published the list since 2006, and the 2014 list is noteworthy in three key ways.

First, fewer global challengers dropped off the list than in the past, signaling that they are acquiring more sustainable advantages beyond a large home market and low-cost labor.

Second, challengers emerged in new consumer categories, such as fast foods, represented by companies such as the Philippines’s Jollibee Foods, with 2,000 restaurants; and wine and spirits, represented by Chile’s Concha y Toro, the world’s seventh-largest winery, and Thailand’s Thai Beverage. These additions show both the growing purchasing power of the middle class in emerging markets and the success of these companies.

Third, five companies graduated from the list to become global leaders in their industries, compared with just two in 2013. This year’s graduates include Mexico’s Grupo Bimbo, the world’s largest baker, and two Chinese companies, Huawei Technologies, the world’s largest telecom-equipment supplier, and Lenovo Group, the world largest PC maker.

Here are some other highlights of this year’s list:

- Each group of global challengers is more diverse than the prior one. With the addition of the Philippines this year, the 2014 global challengers are headquartered in 18 countries, nearly double the ten countries represented in the inaugural 2006 list.

- In that first list, China and India supplied nearly two-thirds of the challengers. In 2014, the number of Chinese and Indian challengers has fallen below 50 percent for the first time. Smaller countries are picking up the slack. Thailand (five challengers), Turkey (four), and Chile (three) are at all-time highs .

- Global challengers are growing more quickly than comparable companies. From 2000 through 2013, the revenues of global challengers grew by an annual average of 18 percent, compared with 7 percent for global peers and 6 percent for the nonfinancial S&P 500. (For a statistical snapshot of the challengers, see the exhibit below.)

Making the Cut

There were 13 newcomers to the list this year, and each of them became a part of the group by excelling in one of three areas.

Capturing Middle-Class Consumers. Between 2009 and 2020, the size of the global middle class will expand from 1.8 billion to 3.2 billion—and nearly all of the new members will live in emerging markets. Challengers from fast-moving-consumer-goods, TMT, and other consumer-facing companies are prepared to serve them. Among the new challengers, four, or 31 percent, are consumer goods companies, and two, or 15 percent, are TMT companies.

Concha y Toro, based in Chile, for example, is the first luxury-goods company to become a global challenger. It is the largest Latin American wine producer and the seventh largest in the world. The company, with $950 million in sales, has vineyards in Chile, Argentina, and the U.S. It is one of the few winemakers trying to create a global brand, as evidenced by its sponsorship of the Manchester United Football Club. Despite flat wine consumption globally, Concha y Toro increased revenues at an annual rate of 5 percent from 2011 through 2013. Exports, which account for 68 percent of revenue, are growing at an even faster clip.

Meeting Digital Needs. Many companies in emerging markets have been rapidly developing innovative and advanced digital services, helping consumers improve their lives and companies strengthen their capabilities.

Tencent Holdings, based in China, is one of two new challengers in the technology, media, and telecommunications industry. It is one of the top three most valuable Internet companies in the world ranked by market capitalization and the first global challenger whose roots are wholly online. Tencent recently began expanding overseas and is already generating 7 percent of revenues outside China. Of the 600 million users of its WeChat social-messaging service, 100 million are located overseas. The company is investing heavily overseas in gaming, where it generates more than one-half of its revenues. For example, Tencent now owns Riot Games, the studio that created League of Legends. Tencent generated $9.8 billion in revenues in 2013, and it recorded 46 percent annual revenue growth from 2011 through 2013.

Building and Supplying the World. Seven of the newcomers belong to the industrial goods and resources sectors from which global challengers have traditionally come. But their success is increasingly driven by innovation rather than low costs.

EuroChem Mineral and Chemical, based in Russia, is a top ten fertilizer producer today and aims to break into the top five and go public in the next few years. Its business model is built around vertical integration, pulling raw materials out of the ground and producing and distributing final products. EuroChem announced plans in 2013 to build a $1.5 billion fertilizer plant in the U.S. and form a joint venture with Migao Corporation, a specialty fertilizer producer based in China. Foreign sales accounted for more than 80 percent of EuroChem’s $5.5 billion in revenues in 2013, and revenues grew by 24 percent from 2011 through 2013.

The End of Easy Growth

The work of global challengers is not done. These companies will have to work harder for their success in the future. Their home markets are also becoming more challenging. China’s economy is expanding at the slowest pace in more than a decade, and annual growth in once-booming nations such as Brazil, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa has slowed to about 1.5 to 2.5 percent. They also must compete against the local dynamos—those companies that have consciously decided not to go global. (See 2014 BCG Local Dynamos: How Companies in Emerging Markets Are Winning at Home , BCG report, July 2014.)

Further, global challengers have to take on multinationals, which are becoming smarter in their approach to emerging markets. Some companies—including Hyundai Motor Group and Yum! Brands, which owns the KFC, Pizza Hut, and Taco Bell restaurant chains—have figured out how to customize and localize their products without compromising the advantages of scale, size, and brand.

Finally, global challengers have pursued most of the easy-growth opportunities overseas. They often need to make investments in overseas markets to capture greater market share. But these companies have to be careful about where they place their bets. Will they decide that their long-term strength rests on creating truly global footprints and business models in order to take advantage of the eventual convergence of the growth rates of the two worlds? Or will they retreat back home and to other emerging markets?

These are growing pains—not the end of growth. The global challengers are still in the game. In order to win in this new world, they need to develop three capabilities:

- Brand Building. All companies, but especially those that serve consumers directly, need to sharpen their focus on building brands and consumer engagement in their target markets. Consumer-oriented global challengers currently spend less on marketing than their global competitors, and few emerging-market consumer brands are well known outside their home country. But this can change quickly. With the popularity of online channels in emerging markets, companies can partly bypass traditional and expensive forms of marketing and advertising. They can also gain entry by buying foreign brands. In fact, all four new consumer companies have relied on overseas acquisitions that allowed them to build presences in new markets.

- Localization. Many consumer products need to be tailored to local markets, and tailoring requires strong capabilities in several functions, including R&D, marketing, sales, supply chain, and talent. Jollibee Foods, based in the Philippines, has had great success at home selling hamburgers that appeal to Filipino tastes, but the company stumbled when it entered China with its own Jollibee restaurant in 1998. Jollibee’s Chinese fortunes did not turn until it shifted strategy and started buying local restaurant chains.

- Resisting the Pull of Home. It is probably not a coincidence that the four new challengers in consumer goods are based in Chile, the Philippines, Thailand, and Turkey, rather than the mega-markets of China and India. In fact, among the 16 consumer-goods challengers, only two are based in those countries: Godrej Consumer Products in India and Haier Group in China. Many consumer companies in the large emerging markets have not aggressively expanded overseas because their home market has provided plenty of opportunity for growth. Both Godrej and Haier have shown that it is possible both to serve a large and growing domestic market while expanding abroad. But such a feat requires a steadfast commitment.

From Global Challengers to Global Leaders

While no two companies are the same, many of them face the same challenge of translating the global aspirations of senior leaders into systematic programs that will transform the organization. Based on our work with emerging-market companies, we have created a global “challenger to leader” (C2L) program. C2L helps companies make global ambitions part of their DNA by transforming their people and organization practices, operations, and general go-to-market activities.

While the program addresses 20 initiatives, we focus here on two—talent and innovation—that are especially critical for leaders to address.

Talent. The shortage of talent threatens to undermine growth plans for all global challengers, but especially those seeking to move into new markets. In Indonesia—a country BCG has studied extensively—a 40 to 60 percent gap between the demand for middle managers and the supply will have developed by 2020. (See Tackling Indonesia’s Talent Challenges , BCG Focus, May 2013.)

To make matters worse, almost 60 percent of graduates switch jobs within their first three years of employment, and more than one-third switch jobs two or more times in that period. New employees leave for better offers but also because they are disengaged. The following is a five-part plan of attack that will go a long way toward alleviating shortages and addressing employee dissatisfaction:

- Tapping New Talent Pools. To attract a broader group of qualified potential employees, executives can look in unconventional places and at alternative groups of candidates. These include decent universities in small cities, expatriates who have studied or worked abroad and are open to returning to their native country, retirees seeking part-time work, immigrants, candidates from other industries, and young mothers reentering the corporate world.

- Building Recruitment and Hiring Engines. A well-designed process for bringing on new employees and starting their career development early on can help cut the level of undesired turnover in half during the first year of employment.

- Creating a Meritocracy. Reducing the number of people who must be recruited every year hinges on making the current workforce more engaged, more productive, and better organized. Executives can accomplish this through appropriate organization reviews that aim for fewer structures, leaner processes, and performance-based HR systems.

- Enhancing Middle Management. Senior executives should be paying special attention to the development of middle managers. They should seek to identify high-potential employees early on and invest heavily in them through job rotation, opportunities for project leadership, and a variety of assignments.

- Professionalizing Talent Management. No major company would dream of launching a product without a detailed plan, resources allocated for product distribution, and a marketing campaign. Likewise, executives should professionalize talent management along several dimensions.

Innovation. The success of a company’s innovation activities is generally expressed in the number of patents issued or R&D dollars spent. By that measure, the challengers have a long way to go to catch up. They spend about one-tenth the amount on R&D as the top 100 U.S. patent issuers. Fortunately, they are doubling down on innovation. From 2008 through 2013, the challengers increased their R&D spending by an average of 16 percent, four times faster than the those top U.S. patent issuers.

As global challengers move outside of the protective field of their home markets, they need to start behaving like multinationals in the way they approach talent and innovation. It’s not that multinationals have all the answers—far from it. But they have been developing and professionalizing their practices for longer.

Executives should be carefully assessing their capabilities in order to understand the transformative moves they will need to make. They also have to understand that strengthening their capabilities will likely come at the expense of margins. It is not cheap to be big in many markets. But it is necessary if you want to win over the growing numbers of middle-class consumers in markets close to home. These consumers represent the future of the global economy, and they are there for the taking.