Companies know that innovation is one of the keys to growth. Seventy-five percent of the respondents in BCG’s report Innovation in 2014 (October 2014) ranked innovation as a top-three priority for their company; 22 percent said it was their company’s top priority. More than 60 percent said their company planned to increase investment in innovation in the coming year.

So where are the results?

Companies are the first to admit that there is room for improvement. CEOs question whether they are getting a return commensurate with their investments. Many innovation managers express frustration that their teams are not developing the successful new products and services—or the compelling product or service extensions—that they seek.

Compounding those challenges, the bar is being raised. Customers, used to continuing progress and improvement, expect more. New technologies, especially digital advances, have conditioned customers to expect it more quickly. But long-used innovation models no longer keep up. Processes are too slow, dragged out by too many rigid stages and gates to clear. Decision making has become overly complicated and consensus based, resulting in compromised, incremental solutions with little chance for a big impact.

As customer expectations grow and markets evolve more quickly, companies can’t expect to innovate in the ways they used to. Innovation models themselves need to be systematically innovated, rethought, and updated.

On the basis of our experience working with hundreds of companies to reinvigorate their innovation strategies and processes, we suggest that executives seeking to sharpen their innovation edge follow a few organizing principles.

Approach Innovation as a System

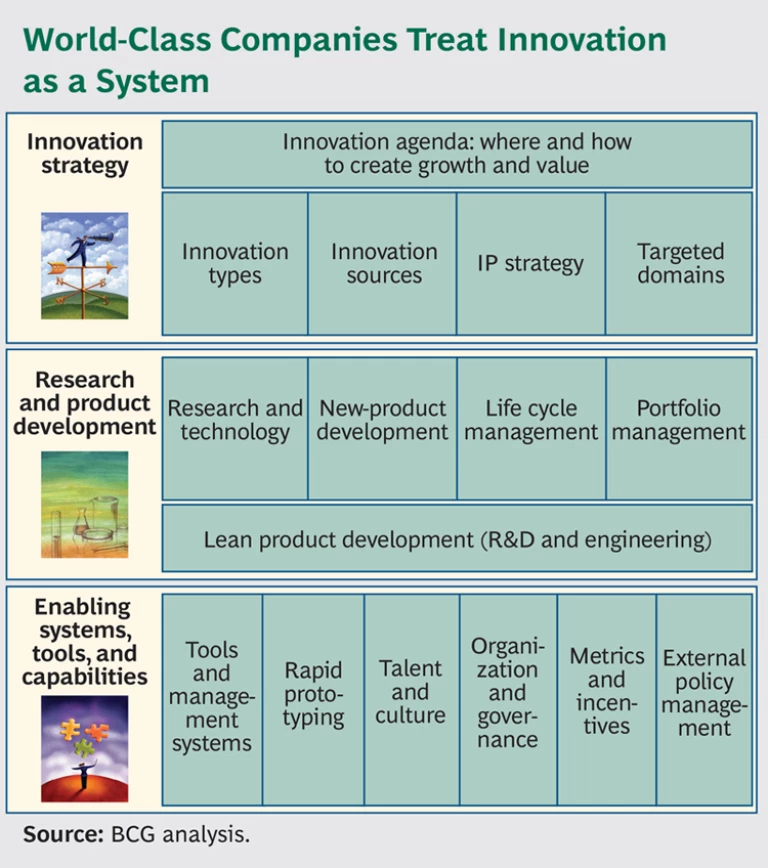

In our view, innovation is a system: a mixture of insight and creativity, as well as a disciplined process that consistently promotes progress. This system has three major components: a strategy comprising choices on where and how to create growth and value through innovation; a supporting set of processes for research and product development; and an enabling set of systems, tools, and capabilities. (See the exhibit, “World-Class Companies Treat Innovation as a System.”) The system should be rooted in experimentation, and, like all adaptive systems, it must evolve over time as the external environment and internal needs change.

Design the System for Speed

When combined with a willingness to fail—see the next organizing principle, below—organizing for speed may be the highest-impact step that companies can take to rejuvenate innovation.

For one thing, bringing new products to market quickly avoids giving competitors early looks or the opportunity to influence trial results (by, for example, cutting the price of an existing product in trial markets). For another, time-consuming trials and test launches too often kill new products before they have a chance to find their market. Splashy launches, supported by big advertising buys, have muted impact in the age of social media and mobile commerce; conversely, it’s possible today to launch new products quickly by using social media and other inexpensive tools.

Reckitt Benckiser, a global consumer-products company that has significantly outperformed its peers in both revenue growth and total shareholder return (TSR) over the past 15 years, has built an organization and a culture that value idea generation, quick decision-making, and, above all, speed. The company encourages ideas from anyone at any level in its organization, as well as from its suppliers and partners. It has systematized idea collection, evaluation, execution, and reward, with speed a top priority at each stage. It invests strongly in new products—one reason why, compared with its rivals, more of Reckitt’s revenue comes from products that are less than three years old. The company’s UK general manager puts it this way: “We rely on speed to create and define new sectors, which grow entire categories. We use our first-mover advantage to take share; and while our competitors are figuring out how to catch up, we’re moving on to new markets.”

Learn by Doing: Fail Fast and Fail Cheap

Failure is as integral to innovation as new ideas. It’s axiomatic that not every idea is going to make it. Adidas readily admits, “There are no blueprints for innovation. Sometimes it takes trial and error. More often than not, we miss the mark.” Domino’s Pizza expanded its menu for the first time to include chicken in April 2014, supporting the change with an ad campaign that stated, “Failure is an option.”

Yet many companies draw out the development and testing process, making failures time-consuming and expensive. These companies might learn a lesson from Wall Street: when a trade heads south, sell quickly and move on.

Failing fast and cheap is partly about making efficient use of scarce resources—by putting them where they have an impact—and partly about capturing lessons learned. Effective innovation systems are designed to limit the waste created by going too far down unproductive paths. The systems, and the executives overseeing them, also help product-development and innovation teams learn to limit risk by cutting losses sooner than a standard innovation playbook might; these teams then make the lessons learned from the experiment available to subsequent projects and teams. Using an adaptive approach, good innovation systems institutionalize taking advantage of the experience curve.

Intuit, for example, employs an iterative process, Design for Delight (D4D), that uses “rapid experiments with customers” to narrow a broad range of options to the few that have significant appeal. The company is not afraid to jettison “failed” ideas along the way, having learned the lessons from them. The quick, iterative nature of the customer experiments keeps the process moving fast and limits costs. Intuit also sponsors periodic “incubation weeks,” in which teams are invited to design and build minimum viable products for testing within a week.

Reach for Big Ideas

Ninety percent of the most disruptive innovators in the 2014 BCG Global Innovators Survey said that developing “new to the world” products is important to their future success, compared with 63 percent of nondisruptive innovators. They also take a longer-term view, with 25 percent investing for a three- to five-year return and 21 percent investing with a time horizon of five years or more. Only 17 percent of the nondisruptive innovators invest with a time frame of five years or more.

Nonetheless, many companies still suffer from a cautious culture, misguided incentives, and fearful decision-making and governance. As a result, they make incremental improvements to products rather than introducing a greater number of new and radical products. More companies need to add boldness to the value mix.

Leading innovators are increasingly looking to big data for big ideas. Almost 60 percent of strong innovators in our 2014 survey said that their companies mine big data for new-product ideas, compared with only 19 percent of weak innovators. BCG research into big-data leaders shows that these companies generate 12 percent more revenue than those that do not experiment with big data. They are also twice as likely to credit big data with making them more innovative (81 percent compared with 41 percent) than their peers.

Another technique enjoying an increasingly wide resurgence is the corporate incubator. Incubators more or less evaporated when the dot-com bubble burst, but BCG research indicates that they are making a comeback—with a twist. Rather than considering investments solely on the basis of financial returns, the new generation of incubators concentrate their investments in ideas that can enhance the sponsoring company’s competitive advantage. The start-ups selected for incubation have significant interactions with their corporate sponsor beyond simply cash support, including access to R&D, supply chains, and key customers at both the corporate and business-unit levels.

Our analysis of the top 30 companies (as measured by market value) in each of six innovation-intensive industries (telecommunications, technology, media and publishing, consumer goods, automotive, and chemicals) found that in 2013 alone, 19 of the 180 companies had established incubators—or their close relatives, accelerators. The larger companies in the sample (as measured by market value) were more likely to have embraced the trend. More than one-third of the top 10 companies in the sample, 26 out of 60, had established incubators or accelerators, compared with less than one-quarter, 42 out of 180, of the sample as a whole. (See Incubators, Accelerators, Venturing, and More , BCG report, June 2014.)

Institutionalize IP

Innovation both depends on and generates intellectual property. And it’s not just a tech thing. Smart companies across all industries increasingly use IP as both an offensive and a defensive competitive weapon—and disruptive innovators take it even more seriously. IP winners take a strategic approach that embraces six broad practices. They focus on value, putting a price on the value generated by their innovations. They protect and further their freedom to operate by managing their own portfolios, with the aim of ensuring affordable access to the IP they need now and will need in the future. They keep their eyes on the future, tracking the moves of competitors and anticipating the direction of technological and innovation trends. They have lean and focused organizations. They view the IP function as a strategic partner of the business units, not as an administrative or staff unit. They put a premium on speed, particularly with respect to patent filings to protect their innovations. And they focus on quality over quantity. (See “ Six Habits of IP Winners ,” part of The Most Innovative Companies 2013 , BCG report, September 2013.)

Companies that manage their IP assets effectively are more successful than their competitors at winning approval for their applications, securing patents more than 60 percent of the time. They control a disproportionate share of the IP within their industries, measured not necessarily by raw numbers of applications and claims but by breadth and depth of coverage.

“Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing,” goes the famous football adage. For companies whose lifeblood is new products and services, the same can be said of innovation. These companies organize themselves systemically to keep the lifeblood flowing, and they put themselves through regular checkups to make sure the system is working as it’s supposed to. They think big, move fast, and are not afraid to fail. And when necessary, they don’t hesitate to innovate their innovation systems to keep the lifeblood flowing.

Where does your company stand?