The Boston Consulting Group’s Strategy Institute is taking a fresh look at some of BCG’s classic thinking on strategy to explore its relevance to today’s business environment. This article, the fourth in the series, examines the growth share matrix, a portfolio management tool developed by BCG founder Bruce Henderson.

We are managing our businesses with a laser-like focus on return on capital … rigorously testing our portfolio to identify which businesses to grow, run for cash, fix or sell.

—The Dow Chemical Company, Annual Report 2012

BCG Classics Revisited

More than 40 years after Bruce Henderson popularized BCG’s growth share matrix , the concept is very much alive. Companies continue to need a method to manage their portfolio of products, R&D investments, and business units in a disciplined and systematic way. Harvard Business Review recently named it one of the frameworks that changed the world. The matrix is central in business school teaching on strategy.

At the same time, the world has changed in ways that have a fundamental impact on the original intent of the matrix: since 1970, when it was introduced, conglomerates have become less prevalent, change has accelerated, and competitive advantage has become less durable. Given all that, is the BCG growth-share matrix still relevant? Yes, but with some important enhancements.

The Original Matrix

A company should have a portfolio of products with different growth rates and different market shares. The portfolio composition is a function of the balance between cash flows.… Margins and cash generated are a function of market share.

—Bruce Henderson, “The Product Portfolio,” 1970

At the height of its success, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the growth share matrix (or approaches based on it) was used by about half of all Fortune 500 companies,

The matrix helped companies decide which markets and business units to invest in on the basis of two factors—company competitiveness and market attractiveness—with the underlying drivers for these factors being relative market share and growth rate, respectively. The logic was that market leadership, expressed through high relative share, resulted in sustainably superior returns. In the long run, the market leader obtained a self-reinforcing cost advantage through scale and experience that competitors found difficult to replicate. High growth rates signaled the markets in which leadership could be most easily built.

Putting these drivers in a matrix revealed four quadrants, each with a specific strategic imperative. Low-growth, high-share “cash cows” should be milked for cash to reinvest in high-growth, high-share “stars” with high future potential. High-growth, low-share “question marks” should be invested in or discarded, depending on their chances of becoming stars. Low-share, low-growth “pets” are essentially worthless and should be liquidated, divested, or repositioned given that their current positioning is unlikely to ever generate cash.

The utility of the matrix in practice was twofold:

- The matrix provided conglomerates and diversified industrial companies with a logic to redeploy cash from cash cows to business units with higher growth potential. This came at a time when units often kept and reinvested their own cash—which in some cases had the effect of continuously decreasing returns on investment. Conglomerates that allocated cash smartly gained an advantage.

- It also provided companies with a simple but powerful tool for maximizing the competitiveness, value, and sustainability of their business by allowing them to strike the right balance between the exploitation of mature businesses and the exploration of new businesses to secure future growth.

The BCG Matrix in a Changing World

The world has changed. Conglomerates have become far less prevalent since their heyday in the 1970s. More importantly, the business environment has changed.

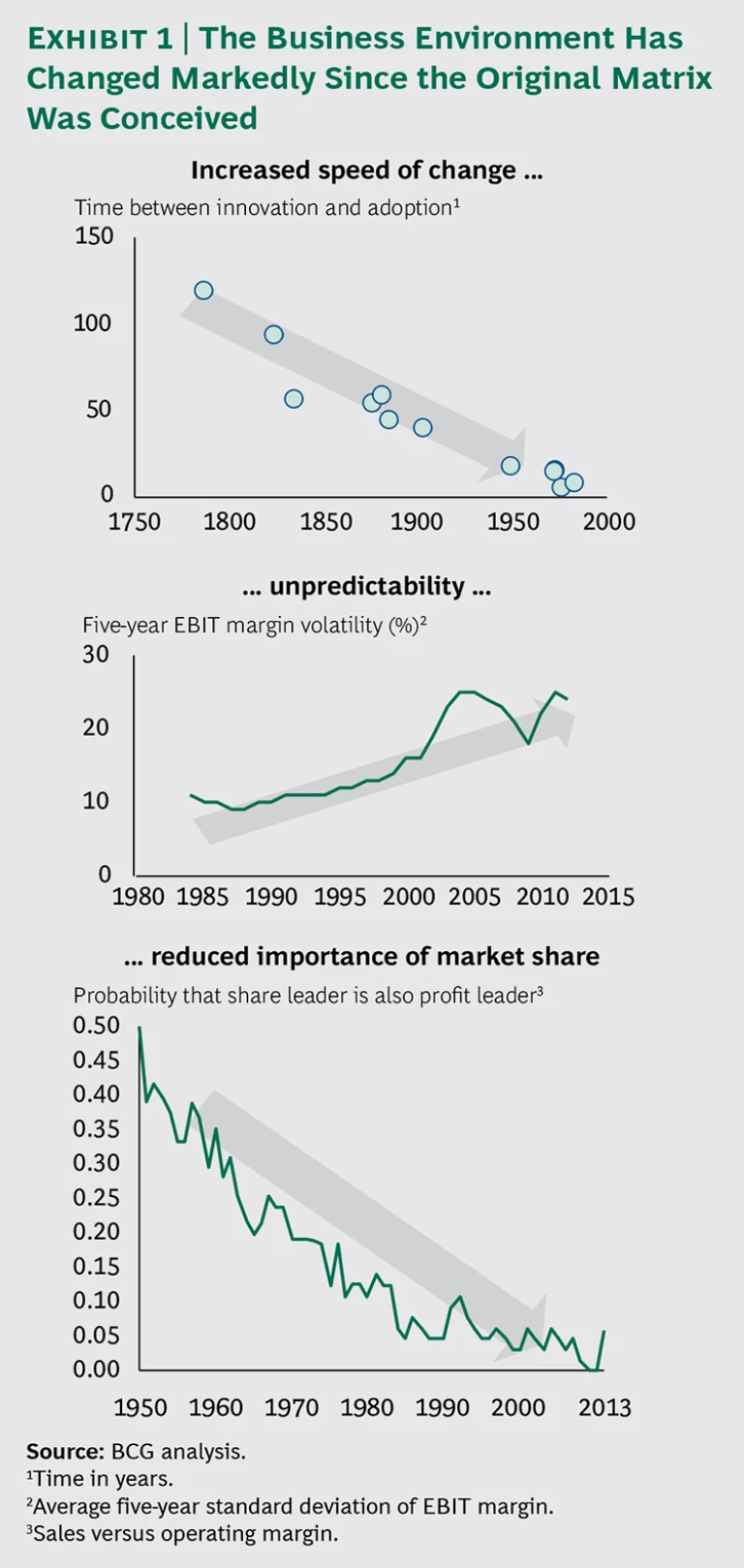

First, companies face circumstances that change more rapidly and unpredictably than ever before because of technological advances and other factors. As a result, companies need to constantly renew their advantage, increasing the speed at which they shift resources among products and business units. Second, market share is no longer a direct predictor of sustained performance. (See Exhibit 1.) In addition to share, we now see new drivers of competitive advantage, such as the ability to adapt to changing circumstances or to shape them.

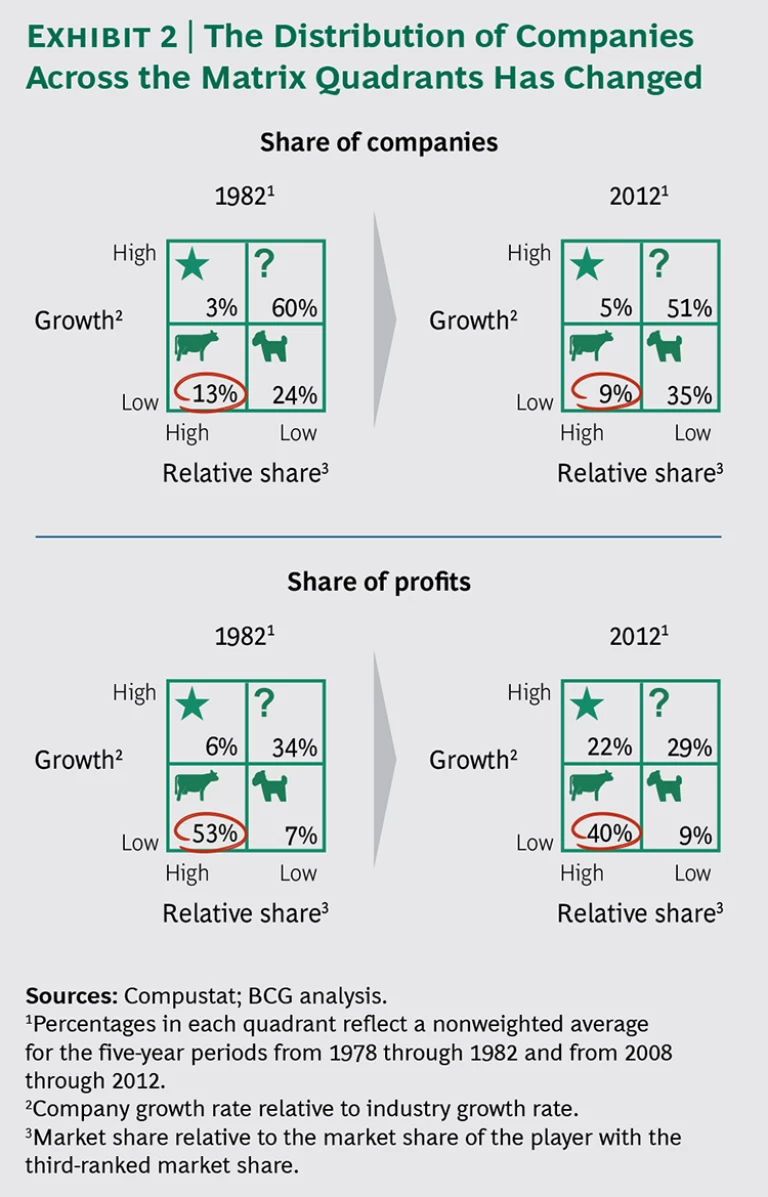

So, what do these two shifts mean for the original portfolio concept? We might expect that these developments translate into changes in the distribution of businesses across the matrix. As change accelerates, we may see that businesses move around the matrix quadrants more quickly. Similarly, as the disruption of mature businesses increases with change and unpredictability, we may see proportionately lower numbers of cash cows because their longevity is likely in many cases to be curtailed.

To test these hypotheses, we looked closely at the effect of these changes in the U.S. economy, by treating individual companies as analogues for individual business units in a conglomerate’s portfolio. In our analysis, we assigned every publicly listed U.S. company to a portfolio quadrant, on the basis of its growth rate and market

The results robustly support the hypotheses.

First, companies indeed circulated through the matrix quadrants faster in the five-year period from 2008 through 2012 than in the five-year period from 1988 through 1992. This was true in 75 percent of industries, reflecting the higher rate of change in business overall. In those industries, the average time spent in a quadrant halved: from four years in 1992 to less than two years in 2012. To further test this hypothesis, we also studied ten of the largest U.S. conglomerates and discovered that the average time any business unit spent in a quadrant was less than two years in

Second, our analysis showed the breakdown of the relationship between relative market share and sustained competitiveness. Cash generation is less tied to mature businesses with high market share: in our analysis of public companies, the share of total profits captured by cash cows in 2012 was 25 percent lower than it was in 1982. (See Exhibit 2.) At the same time, the duration of that later part of the life cycle declined as well, on average by 55 percent in those industries that witnessed faster matrix circulation.

The Continued Relevance of the BCG Matrix

We keep speed in mind with each new product we release…. And we continue to work on making it all go even faster…. We’re always looking for new places where we can make a difference.

—Google’s company-philosophy statement

Given the rapid pace and unpredictable nature of change in today’s marketplace, the question arises: Has the matrix lost its value?

No, on the contrary. However, its significance has changed: it needs to be applied with greater speed and with more of a focus on strategic experimentation to allow adaptation to an increasingly unpredictable business environment. The matrix also requires a new measure of competitiveness to replace its horizontal axis now that market share is no longer a strong predictor of performance. Finally, the matrix needs to be embedded more deeply into organization behavior to facilitate its use for strategic experimentation.

Successful companies nowadays need to explore new products, markets, and business models more frequently to continuously renew their advantage through disciplined experimentation. They also need to do so more systematically to avoid wasting resources, a function the matrix has successfully fulfilled for decades. This new experimental approach requires companies to invest in more question marks, experiment with them in a quicker and more economical way than competitors, and systematically select promising ones to grow into stars. At the same time, companies need to be prepared to respond to changes in the marketplace, cashing out stars and retiring cows more quickly and maximizing the information value of pets.

Google is a prime example of such an experimental approach to portfolio management, as expressed in its mission statement: “Through innovation and iteration, we aim to take things that work well and improve upon them in unexpected ways.” Its portfolio is a balanced mixture of relatively mature businesses such as AdWords and AdSense, rapidly growing products such as Android, and more nascent ones such as Glass and the driverless car.

But at Google, portfolio management is not just a high-level analytical exercise. It is embedded in organizational capabilities that facilitate strategic experimentation. Google’s well-known exploratory culture ensures that a large number of ideas get generated. From these question marks, a few are selected, on the basis of rigorous and deep analytics. Subsequently, they are tried out on a restricted basis, before being scaled up.

Gmail and Glass, for instance, were launched among a select group of enthusiasts. Such early testing not only keeps costs per question mark down but also helps the company reduce the risk of new-product launches. After launch, Google leverages deep analytics to continuously monitor portfolio health and move products around the matrix. As a result, it is able to launch and divest approximately 10 to 15 projects every year.

BCG Matrix 2.0 in Practice

To get the most out of the matrix for successful experimentation in the modern business environment, companies need to focus on four practical imperatives:

Accelerate. It is critical to evaluate the portfolio frequently. Businesses should increase their strategic clock-speed to match that of the environment, with shorter planning cycles and feedback loops requiring simplified approval processes for investment and divestment decisions.

Balance exploration and exploitation. This requires having an adequate number of question marks while simultaneously maximizing the benefits of both cows and pets:

- Increase the number of question marks. This requires a culture that encourages risk taking, tolerates failure, and allows challenges to the status quo.

- Test question marks quickly and economically. Successful experimenters achieve this by using rapid (for example, virtual) tests that limit the cost of failure.

- Milk cows efficiently. Successful companies do not neglect the need to exploit existing sources of advantage. They milk low-growth businesses by improving profitability through incremental innovation and streamlining of operations.

- Keep pets on a short leash. With experimentation comes failure: our analysis found that the number of pets increased by almost 50 percent in 30 years. Although Bruce Henderson asserted that pets were worthless, today’s successful companies capture failure signals from pets to inform future decisions on where and how to experiment. Additionally, they attempt to lower exit barriers and move quickly to squeeze out remaining value before divestment.

Select rigorously. Companies must carefully select investments as well as divestments. Successful companies leverage a wide range of data sources and develop predictive analytics to determine which question marks should be scaled up through increased investment and which pets and cows to divest proactively.

Measure and manage portfolio economics of experimentation. Understanding the experimentation level required to maintain growth is important for long-term sustainability:

- Manage the rate of experimentation. Successful companies continually measure and manage the number and costs of the question marks they generate to ensure their pipeline stays filled.

- Drive new product and business success. Companies need to ensure that the probability that question marks become stars is high enough—and that the cost of failure for these question marks is acceptable—in order to sustain growth from new products.

- Maintain a portfolio balance. Successful companies look for today’s stars (and question marks) to ultimately generate at least enough profitability to replace cows (and pets) that are later in their life cycle so that the company portfolio generates sufficient profitability in the long run.

Increasing change certainly requires companies to adjust how they apply the matrix. But it does not undercut the power of the original concept. What Bruce Henderson wrote years ago still holds today, perhaps even more so than ever: “The need for a portfolio of businesses becomes obvious. Every company needs products in which to invest cash. Every company needs products that generate cash. And every product should eventually be a cash generator; otherwise it is worthless. Only a diversified company with a balanced portfolio can use its strengths to truly capitalize on its growth opportunities.”