Successful innovators, both strong and breakthrough, work hard to make sure that the value of innovation is reflected in their corporate cultures and that they are organized to move new ideas forward. Innovation is recognized and rewarded at these companies. Structures and processes are often designed to sidestep the big-organization pressures that can bury a new product or idea before it has the chance to demonstrate its value.

The Most Innovative Companies 2014

The Most Innovative Companies 2014

- Innovation in 2014

- A Digital Disconnect in Innovation?

- Setting a Foundation for Breakthrough Innovation

Innovation as a Cultural Imperative

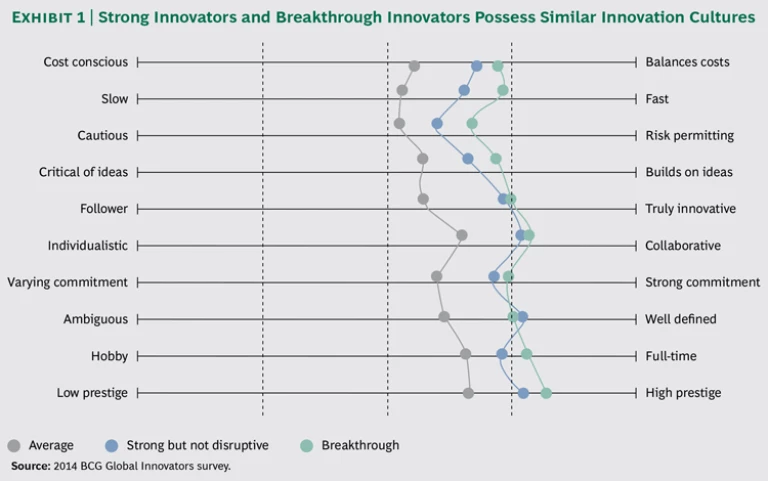

Anyone who doubts the importance of culture to successful innovation should spend some time examining Exhibit 1. The gap between strong innovators on every single cultural attribute—from speed to risk taking, from collaboration to prestige—is expansive. Strong innovators put a high value on innovation—being involved carries prestige within their

Breakthrough innovators take several of these attributes even further. They seek to move faster, they are more willing to take risks, they embrace ideas more enthusiastically, and they elevate the prestige of innovation in their companies. None of these attributes should be that surprising. But the cultures of most large organizations tend to thwart innovation rather than promote it. Bureaucracy, cost consciousness, and caution come to define the way many companies operate. Strong and breakthrough innovators combat the creep of such characteristics every day.

One large global company that maintains a culture committed to innovation is the global consumer-products marketer Reckitt Benckiser, whose brands include Dr. Scholl’s, Calgon, Woolite, and Lysol. The company actively seeks to create new categories with its product-development efforts, and it has consistently generated a higher proportion of its annual sales from products launched over the previous three years than have its rivals. Sales grew by an average 9.3 percent with the underlying earnings-before-interest-and-taxes margin increasing from 14 percent to 26 percent from 2000 through 2013. Its culture is built on four pillars:

- Ideas can come from anywhere. The company believes innovation starts and ends with the consumer. Every employee is encouraged to be on the lookout for new ideas related not only to new products but also to ingredients and combinations, marketing concepts, and packaging. The company is happy to take ideas from, for example, employees at any level, customers, suppliers, and academic experts. It maintains “idealink,” an open, Web-based platform in seven languages where anyone can submit innovation ideas.

- Speed is paramount. Fast decision-making processes are based on an organization structure that gives substantial independence to regional and national teams. Moreover, the regional structure enables speed by grouping together markets with similar characteristics, such as the developed markets of North America and Europe. This structure, for example, enabled the company to acquire U.S.-based supplements company Schiff in December 2013, integrate it by May 2013, and by November announce that the company’s successful heart-health supplement, MegaRed, would be introduced in more than 20 markets across Europe by early 2014.

- The company competes both defensively and offensively in each of its markets and categories, using innovation to spearhead its offense. It seeks to intimately understand competitors and their strategies; it backs its products, including new products, with aggressive marketing trade budgets; and it rewards aggressive execution through a variable-compensation scheme that includes incentives up to three times higher than what its major competitors offer.

- It puts a high value on lean operations, maintaining an entrepreneurial spirit that emphasizes cost control.

Reckitt Benckiser’s CEO, Rakesh Kapoor, puts it this way: “Talented people don’t want to work in bureaucracies. They want to work in companies where they can get things done. This is why we focus so much on our culture. You have to act like a small company. Size can give you scale, but for innovation, speed is more critical.”

In a very different industry, Shell has established an “idea portal” called GameChanger through which employees can submit ideas through a website to a group of 25 full-time professionals in each of Shell’s primary business sectors. The program is backed by an annual budget of $40 million. Employees are permitted to take time away from their day jobs to explore ideas. As proposals turn into business plans, employees may receive $300,000 to $500,000 in initial funding from GameChanger. Some 10 percent of ventures leave GameChanger and are moved into one of the company’s divisions or to Shell Technology Ventures. GameChanger has generated 1,600 proposals since 1996, and fully 40 percent of all the development projects in Shell’s exploration and production business started out as GameChanger ventures.

Organizational Priority

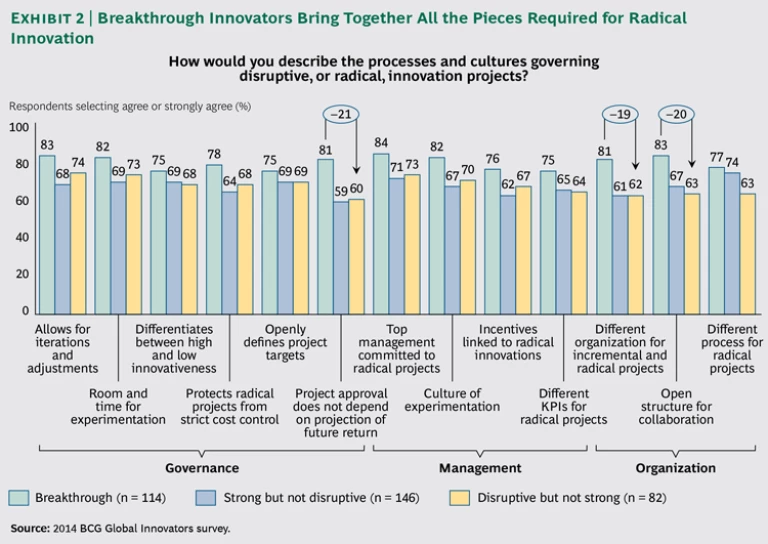

Breakthrough innovators are especially effective at bringing together the pieces required for radical innovation and organizing them for high impact. This is no small achievement. There are at least a dozen factors related to management, governance, and organization design that can have a major impact on any company’s innovation program. Most companies struggle to master a few of these. Breakthrough innovators corral them all. (See Exhibit 2.)

- Management. Top management is commitment to radical-innovation efforts. It backs its commitment with the willingness to green-light radical-innovation projects based on nonspecific or nonfinancial expectations of success rather than projected future returns. Management uses KPIs for radical and incremental projects. It links incentives, recognition, and appraisals to an individual’s contribution to radical innovations. Three-quarters of breakthrough innovators link incentives to radical innovations.

- Governance. Breakthrough innovators differentiate clearly among projects with low and high degrees of innovativeness and use different processes for radical and incremental R&D projects. Radical projects initially are permitted to have more openly defined project targets. Radical innovation processes allow for iterations and adjustments of initial plans to give individuals and teams ample room and time for experimentation. Breakthrough innovators protect radical innovation projects from strict cost-control regimes. More than 80 percent of breakthrough innovators allow projects to start with no projection of future returns.

- Organization. Three-quarters of breakthrough companies use different processes and KPIs for radical innovation projects. They maintain open organization structures for radical-innovation entities that easily allow for collaboration with internal and external partners. They promote a culture of experimentation and testing that characterizes the radical innovation team.

Centralization and Incubation

By definition, breakthrough innovation is the introduction of new ideas that drive a different way of doing things. This requires risk taking, of course, since no one can foresee the outcome or results of such initiatives. Breakthrough innovators are willing to make decisions and choices as much on the basis of intuition and insight as on data and forecasts—they bet on people rather than manage a process.

In our experience, a dedicated environment is required to promote this kind of approach. And indeed, across all companies and industries, there is a growing trend toward a centralized approach to innovation and product development—meaning that these functions and processes are either controlled and driven by a centralized organization, or a centralized organization conducts R&D and passes the framework for new products and services to business units or regional units for development and launch. This trend is even more pronounced among strong innovators, with those pursuing a centralized approach rising from 68 percent in 2013 to 71 percent in 2014. Similarly, about 70 percent of disruptive innovators also lean toward a more centralized approach. Two-thirds of all breakthrough innovators stated that all innovation and product development is controlled and driven by a centralized organization, at least in its initial stages. More than 70 percent have a different organizational entity for managing radical innovation.

Some breakthrough innovators manage to use the entire company as a new-idea laboratory. Apple under the late Steve Jobs is perhaps the best-known example. Google’s policy of encouraging employees to spend 20 percent of their time working on their own ideas is another. The 3M Company sets the goal of earning 30 percent of its revenues from products introduced in the past five years, and the company aligns its culture and incentives accordingly. It has long allowed its employees to spend up to 15 percent of their time on projects of their choosing. But such companies are for more the exception than the rule.

A more likely approach for most is establishing a dedicated innovation entity. One major energy company has a division with 10,000 employees who are focused on technology and R&D and report directly to the CEO. Like others, this company understands that it is critical for such entities to have the full support of top management and sufficient backing in terms of both financial resources and the time required to get major innovations off the ground. Decentralized organizations tend to dilute the risk-taking authority, allocating smaller budgets and not providing the risk takers with top management backing or the time they need to succeed. As Barry Calpino, vice president of breakthrough innovation at Kraft Foods, recently told Knowledge@Wharton, “…the number one consistent cause of failure is not investing in a good idea beyond just the launch period. You have to stay with it. The ones I’ve been part of that have been big wins have been [instances] where we’ve stuck with it, we’ve invested behind it, and we’ve realized that to get something new to stick, it doesn’t just happen quickly—you have to have staying power.”

Another approach enjoying increasingly wide trial is the corporate incubator. Incubators more or less evaporated when the dot-com bubble burst, but BCG research indicates that they are making a comeback—with a twist. The new generation of incubators is focused on incubating ideas that can have a direct impact on the sponsoring company’s business, not just creating stand-alone companies. The start-ups selected for incubation have interactions with their corporate sponsor that go beyond simple cash support, including access to R&D, supply chains, and important customers at both the corporate and the business unit levels.

Our analysis of the top 30 companies (as measured by market value) in each of the six innovation-intensive industries (telecommunications, technology, media and publishing, consumer goods, automotive, and chemicals) found that 19 of the 180 companies had established incubators—or their close relatives, accelerators—in 2013 alone. In all six industries, 43 percent of the top ten companies (as measured by market value) have established incubators or accelerators, compared with 23 percent of the top 30. (See Incubators, Accelerators, Venturing, and More, BCG Focus, June 2014.)

Breakthrough innovation programs are the result of organizational prioritization and planning. They are rooted in corporate cultures that value innovation and the individual attributes that help further new-product and service development. The best innovators understand that both these factors are prerequisites for breaking through.