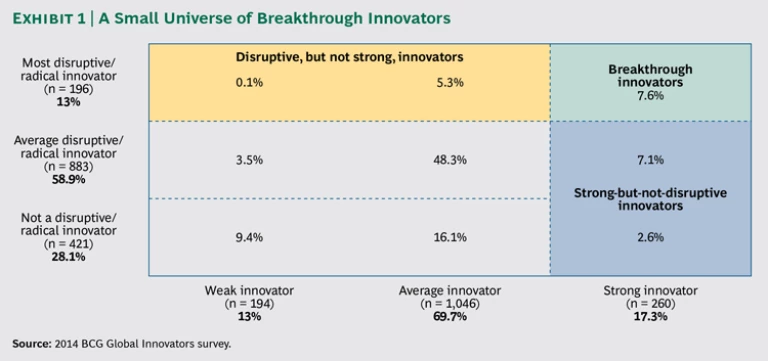

With all the buzz about disruption these days, it’s a bit surprising that only 13 percent of respondents reported that their companies have a significant ambition to deliver radical innovation. More perplexing is that 42 percent of these would-be disruptors indicated that their companies’ innovation capabilities are average at best. Many companies seem more set to break down than break through.

The Most Innovative Companies 2014

The Most Innovative Companies 2014

- Innovation in 2014

- A Digital Disconnect in Innovation?

- A Breakthrough Innovation Culture and Organization

Innovation is hard. Breakthrough innovation is even harder. In our experience, only companies with a foundation of already-strong innovation capabilities can aspire to break through. Too many companies want to shoot for the moon while their innovation programs are barely airborne.

The idea that big companies can replicate the approach of a garage startup is a continuing corporate myth. At big companies, innovation requires commitment, discipline, strong processes, and a willingness to take risks and fail—those latter attributes, especially, are not ones that most corporate cultures embrace. Executives from companies with

Breakthrough Innovators Are Strong Innovators First...

In the 2013 report, we identified five characteristics that differentiate strong innovators and made the point that these are not individual drivers of success; these factors are interconnected and reciprocally reinforcing.

- Strong innovators’ top management is committed to innovation as a source of competitive advantage.

- They leverage their IP both to exclude rivals and to build markets.

- They pursue a portfolio approach for risk taking, leverage internal and external sources of knowledge, and have strong corporate governance and a dedicated budget for venturing and testing concepts.

- They have a strong customer focus—concentrating on releasing products that customers will embrace rather than pushing new technologies simply because they are novel.

- They insist on strong processes that strive for speed and both embrace and manage failure—leading to strong performance.

These attributes are table stakes for breakthrough innovators, which perform just as well as, and often exceed, strong innovators on each one. For example, top management is committed to the efforts of both breakthrough and strong innovators, but respondents from breakthrough innovators reported a higher level of executive commitment to radical innovation (84 percent) than did those from strong innovators without the ambition to disrupt (71 percent). Their innovation programs are more customer focused, and they more often use customer ideas as sources of new ideas. Breakthrough innovators excel at portfolio management, especially at stopping projects they do not believe will pan out, and at managing products once they are in market. They have highly disciplined processes that focus on progress reviews, clear decisions, and on-time completion.

And breakthrough companies exceed strong innovators in their pursuit of IP-based advantage. They are more likely to use IP to exclude others or gain competitive advantage—and to use IP as a lens for portfolio management. But breakthrough innovators don’t just leverage IP more aggressively: they do so more subtly. Tesla Motors, for example, recently announced it will not sue other electric-car makers that use its technologies “in good faith.” Tesla realizes that while it has a formidable patent portfolio, it can’t build the electric-car industry on its own. Moreover, it understands that its patents could discourage others from entering the market. The company is betting that by removing the threat that it will protect its patents, it will accelerate the growth of the market and the infrastructure of charging stations needed to support it. (See “ Tesla’s Gambit: Aligning IP Strategy with Business Strategy ,” BCG article, August 2014.)

…But Stand Out from Strong Innovators in Three Ways

At the highest level, breakthrough innovators put a higher priority on innovation—far more so than other companies do; they know innovation is essential to their future. The top corporate priority at more than half of breakthrough companies (54 percent) is innovation and product development, and it’s a top-three priority at 92 percent of them. But breakthrough innovators differ from the rest in three other specific ways.

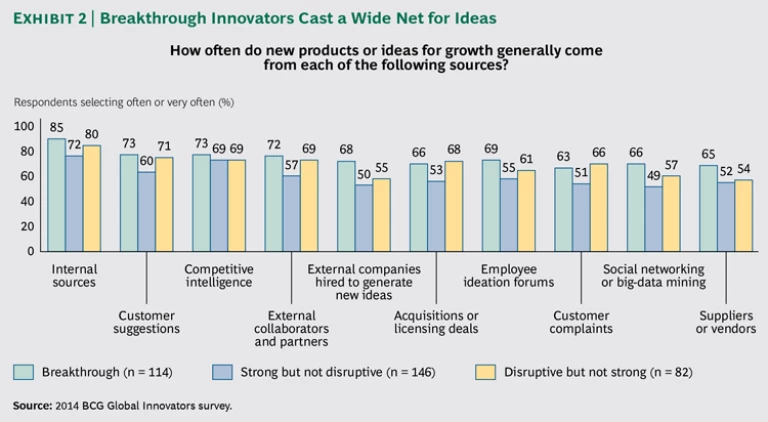

- They cast a wider net for ideas. They are far more likely to generate new product ideas from almost all of ten different sources than either strong or other disruptive innovators. The only two innovation sources on which they lag behind are telling: customer complaints and acquisitions or licensing. The former would be more associated with existing products—and the latter with gaining access to innovations made by others. (See Exhibit 2.)

- They use business model innovation more. Breakthrough products and services increasingly need to be part of a broader business model. Many industrial companies have found that moving from selling products to selling products embedded in a service offers greater differentiation and higher returns. But successfully shifting from a product to a service mind-set requires holistic changes to the underlying business model. Breakthrough innovators understand this and are thus more likely—43 percent compared with 35 percent—to target business model innovation in their innovation efforts than are strong-but-not-disruptive innovators. And breakthrough innovators are nearly twice as likely to use business model innovation as are disruptive-but-not-strong innovators—further suggesting that this latter segment is unlikely to achieve its goals.

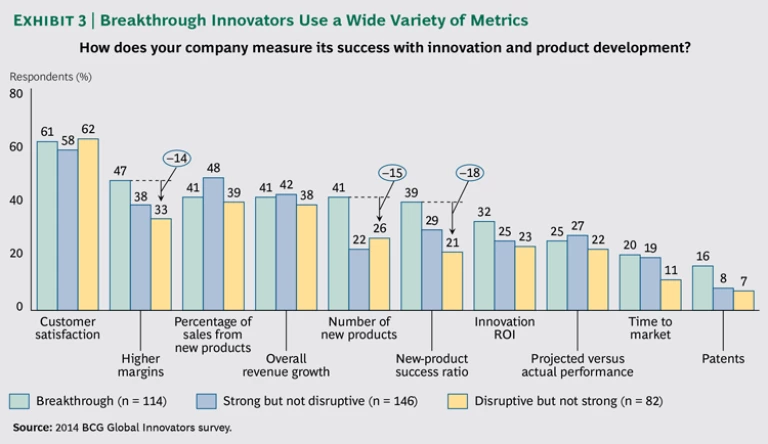

- They have cultures geared toward breakthrough success. They use a wide variety of metrics and KPIs that consider the bottom line, but they go well beyond pure financial returns to contemplate longer-term impacts and competitive advantage. They are much more likely than even strong innovators to track the number of new products and the success ratio of those products. Breakthrough innovators worry about hiring and retaining the right talent and prioritizing ideas for development, while weaker innovators are concerned with funding ideas and moving them through the process. Breakthrough innovators bring a higher degree of focus to their efforts. (See Exhibit 3 and " A Breakthrough Innovation Culture and Organization ," BCG article, October 2014.)

…But Stand Out from Strong Innovators in Three Ways

The proof of these differences can be seen in the results: almost half of breakthrough innovators report generating more than 30 percent of sales from innovations from the prior three years—more than twice the average for all companies.

Perhaps no company exemplifies the ethos of breakthrough innovation better than Amazon. And no company has been more effective at building on what it has learned at each stage of its disruptive development.

Amazon got its start upending the book-publishing business with an online sales model. Then it upended that business again with the e-book. The company has used the lessons learned to expand into myriad other areas of retailing, significantly transforming the consumer purchase pathway and rearranging consumer expectations of what the shopping experience should be. It had embraced thousands of customers as product reviewers and engaged thousands of traditional retailers with the development of Amazon Marketplace. Although it is far from the biggest retailer (Wal-Mart’s annual sales of $475 billion dwarf Amazon’s $75 billion), it is the one retailer that all others in the retail and consumer-packaged-goods sectors must take into account when planning their future strategy. (See “ Secrets of Online Marketplaces ,” BCG article, December 2012.)

Amazon rolls out new products and services with almost frightening speed: the Kindle e-reader, Kindle Fire tablet, the Amazon Fire Phone, Amazon Prime, AmazonFresh, and Subscribe & Save have all been introduced in the past ten years. Amazon Web Services has led the paradigm shift to cloud computing and is a major force in enabling big-data analytics. The company has built one of the biggest and most valuable databases of consumer information based on its 150 million customer accounts. Nobody laughed when Amazon debuted the idea of delivery by drone on CBS’s 60 Minutes.

Several characteristics define Amazon’s disruptive approach throughout its relatively short 30-year history: a long-term horizon, a searing focus on the customer, and a relentless ability to learn from one disruptive move the lessons that could be the basis for the next.

To be sure, not every company wants or needs to break through to the same degree. Perhaps it is not surprising that companies with long innovation cycles, such as industrial-goods and pharmaceutical companies, have less aspiration to be disruptive. And although one could argue that these executives may be underestimating the risks they face, there is a more important issue to address: many more companies out there aspire to break through than have the capabilities to do so. Most will not succeed. But they can improve, and there’s nothing stopping those that truly want to apply themselves—aside from their own institutional constraints—from joining the breakthrough elite. They need to prepare themselves for an arduous process, however. Putting the building blocks in place is an essential first step.