If any Indian industrial sector were well positioned to benefit from the nation’s growing low-cost advantage, cotton fabrics and garments would seem a likely candidate. India is the world’s second-leading exporter of raw cotton and has an immense, growing workforce. What’s more, the cost of Indian labor has remained virtually flat over the past decade when adjusted for productivity gains. That should give India a big advantage in apparel, a sector for which labor accounts for nearly 30 percent of the total cost. By contrast, labor costs in China’s coastal provinces have nearly tripled.

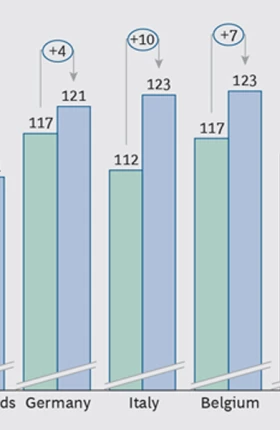

Cost Competitiveness: A Country Guide

Yet India accounts for only 3 percent of the global apparel trade—and there has been no big rush to build cotton textile or apparel plants in India. Instead, much of the country’s raw cotton and yarn is still shipped to China, where it is woven into fabrics and converted into apparel at factories that are primarily located in China, Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

The reasons illustrate the challenges that economies such as India must still overcome before they can fully translate their low-cost advantages into a surge of manufacturing investment and exports across a broad range of industries. In terms of direct manufacturing costs, the new BCG Global Manufacturing Cost-Competitiveness Index shows that India has held steady from 2004 to 2014 relative to the U.S. Within Asia, India has the potential to become a rising regional star. Strong productivity growth and a depreciating currency have offset the increase in average manufacturing wages. Electricity and natural-gas costs have risen less than in most other major Asian export economies since 2004.

But factors other than direct costs undermine India’s competitiveness by adding risk and hidden costs. Bottlenecks at India’s seaports add days to shipping times. It typically takes six months to a year to clear all the regulatory hurdles needed to build a new factory in India. Labor laws that make it difficult and expensive for companies to manage their workforces during slow times discourage companies from building large-scale, cost-efficient factories. And while the government keeps electricity rates low for end consumers, in reality many manufacturers must pay much more for power than in other Asian economies. Because there is a perennial shortage of power capacity in the country, many factories must operate expensive diesel-powered generators on their own.

There is some cause for optimism. Container terminals and expressways are being built and expanded in India, and the growing use of power exchanges is bringing down electricity prices in some industrial areas. In addition, the country is developing special economic zones that offer speedier regulatory approvals and help in managing human resources. The Indian government has also been working harder to promote India as a global manufacturing base.

But fundamental reforms in labor, energy, and investment regulations are required before India can fully capitalize on its low-cost advantage. If the new government can accomplish such reforms, India is in a powerful position to emerge as Asia’s next star in manufacturing.