Explosive demand in Asia for coal, iron ore, and natural gas over the past decade has been an economic boon for resource-rich Australia. The hundreds of billions of dollars that poured into mining, energy, and infrastructure projects created thousands of high-paying jobs and kept Australia’s economy buoyant even through the global recession of 2008 to 2009.

Cost Competitiveness: A Country View

- An Interactive View

- Australia: Losing Ground

- United Kingdom: A Rising Regional Star

- India: Holding Steady

- Mexico: A Rising Global Star

As Australia’s resources sector boomed, however, its manufacturing sector languished. Australia’s automotive industry was especially hard-hit. In 2004, Australia built nearly 400,000 cars valued at some $9 billion. By 2012, output had dropped by nearly half. The worst is yet to come. Ford Australia plans to shut its engine and vehicle plants in 2016; Toyota and General Motors’ Holden subsidiary have announced that their factories will close in 2017. The closures will eliminate thousands of jobs in the plants and in the wider automotive industry.

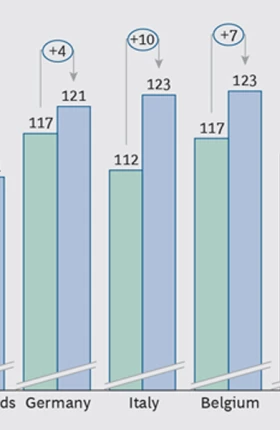

Although the relatively small scale of Australian car-assembly and parts factories made it difficult to compete with larger, more-efficient foreign factories, GM and Toyota both cited Australia’s high production costs and strong dollar as major reasons for pulling out. Our research confirms this sharp deterioration of Australia’s global cost competitiveness in manufacturing. Australia was the worst-performing of the 25 economies in the BCG Global Manufacturing Cost-Competitiveness Index , dropping 21 points relative to the U.S. since 2004 and moving past Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland in average direct costs. Indeed, Australia lost ground in each cost area in our index—wages, productivity, energy, and currency exchange rates.

The resources and infrastructure boom contributed to the loss of cost competitiveness in manufacturing by driving up wages and the Australian dollar and by drawing away capital. Manufacturing wages rose by 48 percent over the past decade, and capital inflows from commodity exports caused Australia’s currency to appreciate by 21 percent against the U.S. dollar. At the same time, overall manufacturing labor productivity fell 1 percent in absolute terms over the ten-year period.

Australia’s anemic performance in manufacturing productivity since 2004 is partly a result of declining capital investment. Annual total real investment surged by more than 60 percent, to $430 billion, from 2004 to 2012, driven by a massive expansion of Australia’s extraction industries. But it fell by 6 percent, to $20.4 billion, in the manufacturing sector. Another factor has been Australia’s low rate of growth in manufacturing productivity, which deteriorated in the second half of the past decade. Inflexible work rules and low investment in skills and labor productivity initiatives contributed to sluggish growth.

The decline in manufacturing may not have seemed to matter much while the rest of the Australian economy was thriving. But with growth slowing in the resources and infrastructure sectors, the value of manufacturing as part of a diversified economy is becoming more apparent. The good news is that the rate of labor productivity growth in other parts of the economy, such as the natural-resources sector, has increased strongly over the past few years. Also, companies have focused again on improving efficiency. Another encouraging sign is that even though jobs have shifted offshore in labor-intensive areas such as textiles, garments, and electronic circuit boards, output of higher-value goods that require innovation and advanced skills—such as precision medical equipment and consumer electronics—is growing. This is an area in which Australia has real capability and, therefore, opportunity.

For Australia to achieve its potential as a manufacturer of high-value products, however, it must improve its cost competitiveness. That will require an increased commitment by both business and government to invest in technology, skill building, productivity initiatives, and capital equipment in sectors in which Australia has a competitive advantage.