If he were alive today, department store magnate John Wanamaker, who famously wondered which half of the money he spent on advertising was wasted, would be doubly frustrated. The odds are that he’d still be misspending—even though the tools and techniques that can finally solve his conundrum would lie within his reach.

Digital’s potential—the delivery of relevant advertisements to interested users at opportune times—has enticed marketers since the earliest days of the World Wide Web. More recently, programmatic buying of display advertising has promised to extend the benefits of digital advertising by using instantaneous data in a real-time environment to reach individuals with relevant messages.

In practice, however, a variety of factors undercut digital advertising’s capabilities. Tests conducted by The Boston Consulting Group show that although current techniques are often effective, companies have an opportunity to achieve significantly better engagement and performance by adopting the latest data-driven approaches—in ways that enhance both relevance and the consumer experience. (See “About This Report.”) Advertisers and agencies are leaving money on the table because of inexperience with these new capabilities, inconsistent campaign execution, and a fragmented approach to campaign development and delivery.

About this Report

Digital advertising can engage with and benefit consumers by delivering highly relevant content in real time, but many advertisers and agencies fail to fully realize this potential. The reasons include inexperience with the latest targeting techniques, inconsistent campaign execution, and fragmentation in campaign strategy and development. To gain an understanding of what overcoming these impediments can mean for the performance of a typical digital-advertising campaign, Google commissioned The Boston Consulting Group to prepare this independent report. The findings outlined in this report have been discussed with Google executives, but BCG is responsible for the analysis and conclusions.

Realizing the Promise

For advertisers and their agencies, better performance is within their grasp. It can be achieved through a powerful combination of data, talent, and technology—learning from the wealth of data that digital technology provides, making full use of the capabilities of digital talent (the new “math men” and “math women”) to optimize campaigns, removing complexity and conflicting incentives, and embracing advanced techniques.

Tests conducted in North America and Europe with five large, diverse, and highly experienced digital advertisers in four industries—consumer products, auto, financial services, and information services—show that advertisers that use new techniques and start to tackle barriers to performance can score big gains. On average, the campaigns in our study that employed the test approach achieved a 32 percent improvement in cost per action (CPA)—the critical metric for most digital campaigns—compared with equivalent campaigns run by the same advertisers that did not use this approach. In some cases, advertisers improved CPA by more than 50 percent.

Our tests included digital display campaigns that employed programmatic, or automated, buying of advertising placements. In addition to the five global advertisers, we worked closely with a number of experienced and sophisticated agencies to identify how to improve performance. The tests demonstrated that the use of advanced targeting techniques can drive increased performance across all major metrics, improving action rates for clicks and view-throughs, in addition to CPA, by as much as 200 percent, and reducing cost per click and cost per view by as much as 70 percent. The advanced techniques employed included search and video remarketing and behavioral analytics, all of which are enabled by programmatic buying. (For definitions and descriptions of digital-advertising metrics and other terms, see the Appendix .)

To achieve these gains in large-scale campaigns, advertisers need to take advantage of the potential to experiment and learn online and make effective use of individuals—in-house or external—with advanced digital skills. Companies that do so will likely experience an even greater impact on performance over time. Additionally, advertisers that address the fragmentation of strategy and execution that occurs in almost every digital-advertising campaign can compound the efficiency and performance benefits.

Digital channels play an increasingly influential and complex role along the entire consumer-purchasing journey. Brands need to be effective online if they want to enhance their influence and impact and build deep relationships with consumers, who have a clear preference for advertising that is relevant and timely—so long as it does not interrupt or pester. (See “The Consumer’s Point of View.”) Achieving a consistently high level of online relevance, by delivering pertinent messages at the right times, requires the use of programmatic buying with real-time bidding.

The Consumer's Point of View

Advertisers worry, appropriately so, that consumers will object to being targeted and resent being tailed around the Web. Marketers need to recognize privacy concerns and focus on building trust with consumers, offering them transparency and choice.

Research shows that consumers, for their part, view digital ads in predominantly pragmatic terms, but they also see lines that should not be crossed.1 When the ads are relevant, timely, and not intrusive, they are welcomed and seen as useful sources of information. If an ad presents a concrete benefit, such as a discount or a new product or service that a consumer was unaware of, even better. As a German consumer put it, “I was looking for a leather rucksack. The ads led me to search on other sites that I would not have gone to.” A French user said, “If I’m looking for a flight for a holiday and it suggests a hotel that I didn’t know about, that’s useful. What’s useless is showing me stuff I’m not interested in.”

The research found that consumers, in general, do not object to targeting; they appreciate receiving relevant content. They are highly sensitive to intrusions, however—ads that interrupt or get in their way—as well as bullying ads that are too pushy. Consumers also object to repetition. “There’s [an ad for] a t-shirt that’s got dogs’ faces that has been chasing me around the Internet for a very long time.... It makes me not want to buyanything from them,”a consumer said.

At the end of the day, the key issue is trust. Consumers are willing to support new uses of personal data—but only if they trust the data user to steward data in ways that will not harm them. (See “In Twitter We Trust… Maybe,” BCG Commentary, January 2014.)

1. “Advertising User Research, U.S. and Europe,” Google User Experience Research, June 2014.

Several major brand and direct advertisers in industries such as consumer packaged goods and financial services have recently signaled their intentions to greatly increase their commitment to programmatic buying. They have good reasons to move fast. Advertisers that are quick to implement more advanced programmatic- targeting techniques, address underperforming campaigns early, and use what they learn in the process to instill cycles of continuous improvement will gain significant competitive advantage over later arrivals to the programmatic party.

Advanced Techniques Deliver Higher Relevance

Standard targeting techniques, such as site-based targeting when used on its own, often do not deliver ads with a high level of relevance to consumers. Site-based targeting, in its simplest form, is the kind of digital targeting that serves ads determined by the content of the website that a consumer is visiting at that moment. For example, someone who surfs a sports-themed website may receive ads for a gym membership. However, site-based targeting does not tell the advertiser whether the sports fan is actually in the market for a new gym. Slightly more sophisticated behavioral targeting uses information collected by the advertiser—potentially in combination with third-party data—to reach consumers based on their previous online activity. This kind of targeting can identify groups of consumers who are actively looking for a new gym by, for example, pinpointing those online (or mobile) users who have browsed Web pages about fitness centers or even visited the membership information page of a fitness center’s website.

The big advantage of behavioral targeting is that it identifies users whose previous online actions more directly indicate that they are likely to be interested in a company’s product or service. It helps uncover what users are considering purchasing. Since behavioral targeting involves deciding whether to buy an impression on a user-by-user basis—in real time—it depends on programmatic buying using real-time bidding. By tracking the consumer’s online actions until time of purchase, it can also ensure that users are not retargeted for what they have already bought or are no longer interested in—an oft-cited shortcoming of digital advertising and an annoyance for consumers.

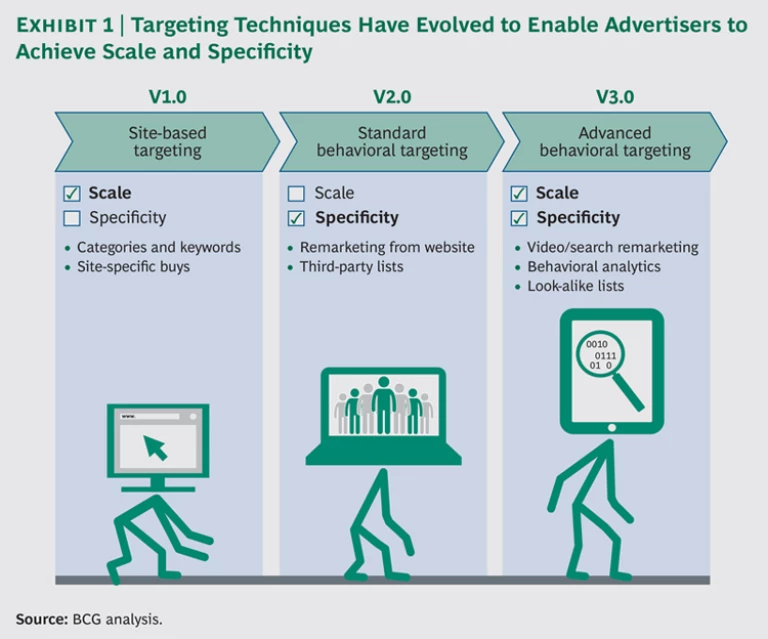

Until recently, advertisers faced a trade-off. Site-based targeting provided campaigns with scale but struggled with delivering relevance on a consistent basis. Standard behavioral targeting could deliver relevance but did not always provide adequate scale. Within the last year or so, some advertisers and their agencies have been employing more data-driven advanced behavioral techniques, in combination with existing techniques, to achieve the best of all worlds: to reach a large-scale, engaged audience with the right message in a cost-effective manner. (See Exhibit 1.)

These data-driven advanced behavioral techniques identify and engage consumers across multiple digital channels. In the case of the fitness center, the advertiser can target users who have viewed the gym’s online videos, clicked on its paid search ads, or engaged with its website in some predefined way. While advanced techniques at first might appear to represent an incremental improvement, our tests found that they actually are a major advance—a step change in capability that has the potential to deliver substantial increases in targeting effectiveness and in user engagement. Even though standard behavioral techniques are often thought to decrease the reach of a campaign, our tests showed that advanced behavioral techniques perform differently. Advertisers can actually maintain reach while increasing performance by identifying new pools of high-value consumers. The increases we experienced were immediate and substantial, and there was also clearly the potential for additional incremental improvement over time.

Many advertisers think that success in digital advertising is mainly a function of moving more money into online channels. Our tests show that how campaigns are constructed matters just as much as the amount of money spent. Those companies that use more advanced, data-driven capabilities will substantially improve performance and—perhaps even more important—gain information and learning that will give them a big advantage over competitors.

How to Improve Engagement

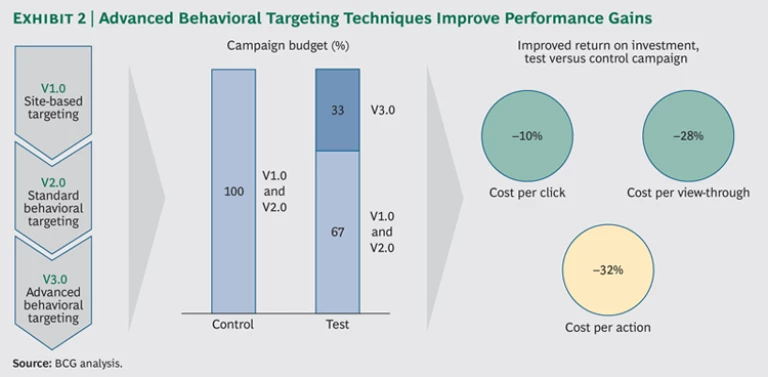

Advertisers and their agencies have the tools they need. By adding advanced techniques to their campaign mix, and reallocating budgets accordingly, the advertisers in our study were able to produce better results in numerous areas—including both reduced costs per action and increased action rates—while maintaining the scale of their campaigns. (See Exhibit 2.) A major automaker, for example, reduced its CPA by 32 percent, its cost per view-through by 29 percent, and its cost per click by 6 percent—while increasing its click-through rate by 36 percent and its view-through rate by 81 percent. (See “Our Methodology.”) Even those advertisers that thought they were operating at a best-practice level or using the latest techniques were surprised to see such gains.

Our Methodology

We used an A/B testing methodology to analyze the impact of advanced techniques on the effectiveness of digital-marketing campaigns. Our study involved five advertisers in four different industries in Europe and North America. For each advertiser, we ran two campaign scenarios—a control and a test group—in parallel for four to six weeks with identical budgets that ranged from $30,000 to $80,000. Both campaigns were expertly planned and executed, and exclusion rules ensured no cross-contamination of users between the groups.

Each control group was designed to be representative of a typical display-advertising campaign and was based on past campaigns that each advertiser had run. The control groups’ campaigns used primarily site-based and standard behavioral targeting techniques. Our test scenario employed the same techniques as the control group but added advanced targeting techniques, such as display remarketing from search ads, video remarketing, and behavioral analytics. In the test groups, advanced techniques accounted for approximately one-third of total spending.

The control and test groups were treated equally at each step of the campaign. For the first week, all techniques were allocated equal budgets. By the second campaign week, the parameters related to individual techniques—such as bid levels and budget pacing—were adjusted to maximize performance. For the final weeks of the study, the worst-performing techniques were dropped and their budgets reassigned to the stronger performers.

Our analysis of performance included clicks, view-throughs, conversions (as defined by the advertiser), and, when possible, user-engagement metrics on the advertiser’s website, including time spent on page, number of pages visited, and bounce rate. The control and test groups were filtered for statistical biases unrelated to advanced targeting. The statistical significances of the performance uplifts among the control and test groups were tested using a resampling approach—and the observed differences in cost per action, cost per click, and cost per view were each found to be statistically significant at 99.9 percent using a one-tailed test.

For a subset of the study, a third baseline scenario was run in parallel to the test and control groups. This scenario included targeting techniques from the control and test groups but displayed a charity ad that was unrelated to the campaign, rather than the campaign creative. This baseline scenario provided a measure of how many of the users being targeted in the control and test scenarios would have viewed through, engaged, or converted even in the absence of a relevant ad.

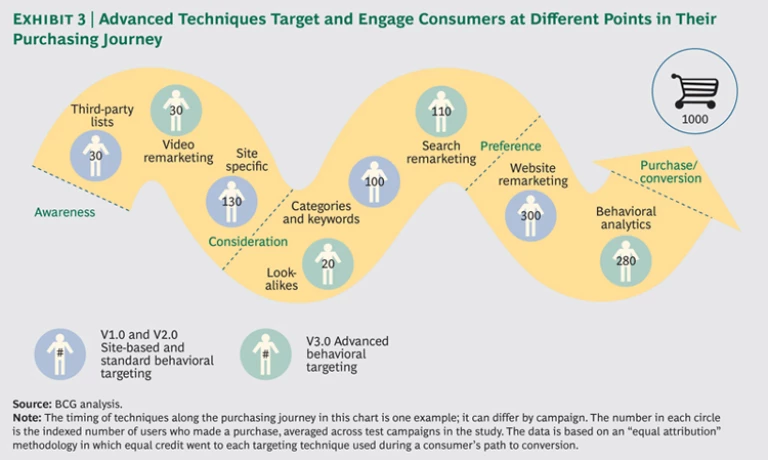

The “freshness” and “completeness” of data available for campaign targeting and optimization is critical to the performance we achieved. Advertisers with a data strategy that ensures data is available in real time (for example, right after a consumer has clicked on a search ad)—and not lost across channels—will have a significant advantage over those that do not. They can target consumers at specific stages of the purchasing journey in ways that those using standard techniques cannot—leading to a higher level of conversions. (See Exhibit 3.)

Advanced targeting also enables the identification of users who are more readily and deeply engaged. In the five-week period of our study, a large North American bank used video and display remarketing from search ads, as well as behavioral analytics, to reach more engaged users who subsequently spent 30,000 more hours and visited 1,000,000 more pages on its website, compared with a control group not targeted using advanced techniques. This means that the average targeted user who then came to the bank’s website spent 30 extra minutes browsing, visited 14 more pages, made seven additional site visits, and had a 10 percent lower bounce rate.

Getting the most out of advanced targeting requires a thoughtful approach to data—in particular, choosing the right metrics for optimization. For example, our tests indicate that view-throughs often have a higher correlation with conversions than clicks—and view-throughs provide more data from which to optimize. But many advertisers have no way of tracking this critical metric and tweaking the campaign based on its performance. One information-services advertiser achieved a reduction of approximately 50 percent in its cost per conversion compared with its best-ever historical performance by employing advanced targeting techniques and by switching optimization to focus on view-throughs. Clicks were not strongly correlated to conversions for this advertiser—and compared with the alternative of using conversions as the metric for optimization, view-throughs provided many more data points during the campaign, thereby enhancing the advertiser’s ability to separate real performance boosts from digital noise.

Sophisticated advertisers—both brand and performance focused—have created “proxy” metrics based on customer engagement and enabled by programmatic buying when the metrics linked directly to campaign goals (such as sales) may not be available or significant. For example, some advanced brand marketers that do not have their own direct e-commerce presence optimize digital campaigns on a cost-per-engagement basis in which prolonged interactions with key Web content are deemed to better correlate with campaign goals than simple clicks or views.

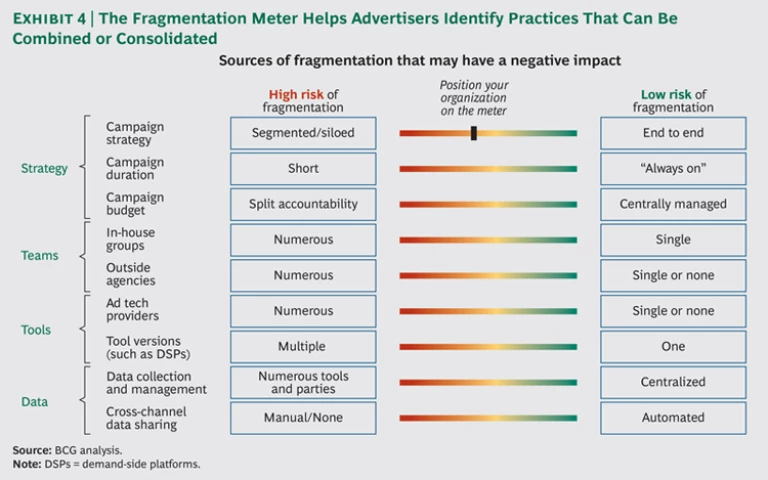

Frustrated by Fragmentation

Most companies do not take full—or anywhere near full—advantage of the advanced technologies currently available to improve targeting, engagement, and performance. Often the biggest impediment is fragmentation. There’s plenty of fragmentation that advertisers cannot address—in audience and devices, for example, not to mention in the digital ecosystem itself. But the fragmentation that takes place in campaign development and execution—in strategy, teams, tools, and data—is within advertisers’ and agencies’ power to control. These forms of fragmentation too often result in conflicting goals and incentives, lack of transparency in performance, wasted effort, and sluggish execution—holding back big gains in performance.

In most campaigns, the fragmentation starts as soon as the strategy is split between online and offline and multiplies as decisions are made with respect to digital-advertising channels (such as search, mobile, video, and display), buying approach (reservation versus programmatic), targeting criteria, and so forth. A major advertiser could not participate in our study because the company divides its digital-display-campaign activity across four separate agency teams—each addressing different parts of the consumer purchasing journey. Since the stages of the journey often overlap, teams working on the same campaign in a real-time bidding environment are bidding against each other to attract the same users. In most cases, the teams do not realize this because they are using different tools that don’t actively communicate with each other. During our study, a targeting technique used by one advertiser suddenly stopped functioning. An investigation revealed that another campaign—for the same advertiser but run by a different team at the same agency—had gone live and was targeting audiences based on precisely the same data but with a higher bid price. There was no process in place to prevent this from occurring. In many such cases, advertisers risk deteriorating performance over time as the price of targeting users rises when competing agency teams attempt to outbid one another.

A much-heard complaint is that it takes an army to execute a campaign. Team fragmentation leads to inefficiency, misalignment of resources, lack of accountability, and sometimes conflicting incentives, among other problems. “You spend so much time getting people to work together [that] it’s dysfunctional,” a vice president of marketing told us. Said another: “Incentives are misaligned across agencies, publishers, [and] tech providers. Digital’s fragmentation forces you to make decisions on where to focus.”

Using unified tools can tackle inefficiencies and enable the design of campaigns based on advanced techniques. As we found in an earlier study of digital-campaign processes, the setup of even standard techniques is often highly inefficient, with only about 20 percent of the activity actually creating value. The balance is taken up in repetitive tasks, waiting time, and approvals. For advanced techniques, this process can be even more complex and inefficient. To address efficiency issues and take full advantage of advanced behavioral targeting techniques, advertisers need to leverage unified tools to connect their media, workflow, and data strategies.

The use of data to optimize targeting is often cut short by a fragmented campaign setup and approach. An ad hoc use of data results in missed opportunities. On several occasions, we came across advertisers that had purchased prime advertising inventory—for example, on the home page or masthead of a major publisher—without properly setting up the mechanisms in advance to collect data from the consumers who were exposed to the ads, missing out on the opportunity to reengage with them. Given the value of consumer insights, it is surprising how many of these opportunities are missed and how many consumer interactions go ignored.

Advertisers also find themselves stuck in a rut of insignificant metrics. A global advertiser requested its agency optimize to a conversion metric that was providing only a handful of data points each day. This made it impossible for the agency to prove that their techniques were driving improvements in performance since the variations were too small to be statistically significant—they could have been random noise. As part of the study, we worked with the agency to identify a proxy metric that was both statistically significant and correlated to the advertiser’s original performance goals.

Five Steps to Improved Performance

Digital advertising is a complex and often inefficient business, but powerful solutions exist for those companies that make the effort to apply them. Last year, BCG mapped and measured the end-to-end processes of 24 digital campaigns across 15 European advertising companies. We found that complexity too often reigned. We identified more than 25 common pain points across the value chain caused by various stakeholders, processes, and tools. Those companies that had determined to get their arms around the complexity, however, realized a saving of staff time of up to 33 percent in their campaign operations. (See Efficiency and Effectiveness in Digital Advertising , BCG Focus, May 2013.) Our 2014 study demonstrates that similar substantial uplifts are possible in targeting and engagement. To achieve them, advertisers need to do five things.

Adopt a unified technology platform. This is a first step that helps pave the way for other improvements, including the use of advanced targeting techniques. Unified technology platforms provide a single user interface and make it possible to source data from a single pool, eliminating the need to reconcile, consolidate, and transfer data among multiple sources. This provides the data “freshness” and “completeness” crucial to achieving good performance in targeting. Unified platforms also allow remarketing lists to be used across tools and channels in advanced targeting techniques such as display remarketing from search ads. An advertiser in our study used a unified platform to make fresh search data available across two separate teams developing search and display campaigns. This allowed for immediate retargeting of consumers who had clicked on a search ad for the brand. Using one set of tools also ensures that teams aren’t cannibalizing performance by bidding against themselves—a phenomenon we witnessed several times during the study.

Among other benefits, unified platforms allow campaigns to launch faster. Agencies can also spend more time gaining insights and fine-tuning campaigns, rather than wasting time on manual downloads and data consolidation.

Implement advanced techniques. Three of the four advanced targeting and engagement techniques tested in our study resulted in substantial improvements in almost all key metrics for all advertisers. With display remarketing from search ads—serving display ads to users who have clicked on a paid search link purchased by the advertiser—marketers can target an additional group of consumers actively searching for a product or service. This technique drove 24 percent of conversions in one test campaign, with a CPA that was approximately half that of the best previously achieved by the advertiser.

Video remarketing involves serving ads to users who have interacted with the advertiser’s video channel. (Interacting, in this case, means either watching a video or subscribing to a channel.) This drove the lowest cost per click for two of the adver-tisers in our study. Moreover, this technique reaches users early in the purchasing journey, when they are only just starting to engage with the brand—often acting as an early driver of conversions overlooked in common last-click attribution models.

The use of behavioral analytics reaches users that have not only visited the advertiser’s website but demonstrated particular behaviors while there, such as spending a certain amount of time or visiting a certain number of pages. When one advertiser remarketed to users who had visited two or more pages, CPA was 26 percent lower than simply remarketing to all website visitors.

Among the advanced techniques we tested, only targeting third-party look-alikes—which relies on identifying third-party lists of users with characteristics akin to an advertiser’s own first-party targets—failed to generate significant improvement. This may be because the quality of third-party lists can vary considerably and our test period did not allow for the extensive trial and error of various lists.

Attack fragmentation. Advertisers generally look to agencies to tackle the fragmentation problem, but it is the advertisers themselves that often mandate multiple strategies and teams to begin with. Advertisers will likely have to take the lead in addressing the issue, which will be a tough challenge. Many bad practices are entrenched, and campaigns rely on multiple parties in their development—some of which have little incentive to change behavior.

Still, there are some basic, no-regrets steps any company can take that will help. These include the following:

Root out the causes of fragmentation. Select a typical digital campaign and map out all the various internal and external people, teams, agencies, and tools involved. This will show where companies sit on the “fragmentation meter” and let ad- vertisers identify practices that can be combined or consolidated. (See Exhibit 4.)

Break down silos. Advertisers and agencies need to make sure everyone involved in running campaigns communicates with each other regularly to discuss how the strategy gets translated into execution.

Connect the data strategy with the overall strategy. Advertisers need to connect their data strategy with their overall strategy, putting in place tools to collect, analyze, and leverage data in a centralized manner. Advertisers also have to make sure that they have the metrics that correlate to and drive the key strategic objectives of the campaign. Having one centralized source of data linked to other tools ensures it is available when and where it is needed.

Get closer to your data. This is one of the marketer’s most potentially valuable assets. Advertisers should ensure that no major digital assets are being underleveraged (video, search, and website)—and that no data is lost along the way. Marketers can test the statistical significance of their metrics and ensure that the important progress indicators of the campaign aren’t just noise—and if they are, test whether better proxy metrics can be created.

Use multiple attribution models. For example, our study found that video is often undervalued in a “last click” attribution model, despite playing a critical role early in the purchasing journey. Further, broad site-based targeting tended to get too much credit.

Bring the math men and women to the table. Marketers and agencies need to augment their digital skills. Strategy and creativity will always be critical to successful campaigns, but the ability to effectively collect, analyze, and use data today is no less essential. Too often, however, companies regard this capability as a stand-alone function segregated from mainstream campaign development. Mathematicians, statisticians, and other analytics experts need to be part of the campaign team and part of ongoing campaign improvements and evaluations. Advertisers should look to structure and train their internal teams to leverage these capabilities—and to work with their agencies to fill skill gaps.

Test and learn. The Internet is the best marketing laboratory yet invented. Direct marketers know this. Because their ultimate metric is online sales, they are adept at testing one technique against another and tweaking campaigns until they get the results they want. Brand marketers can take a page from this book, substituting their own metrics—such as average session duration as well as graphic interaction and information downloading—for direct sales. Our study tested individual campaigns one against another with the goal of seeing whether using advanced techniques could improve effectiveness. We came away convinced that by experimenting further over time, we could readily deliver continuous incremental improvements on top of the already substantial increase of 30 to 50 percent that we achieved.

What Would Wanamaker Do?

John Wanamaker never solved his riddle, but he lacked the tools available to digital advertisers today. Advertisers in the digital age have the ability to engage with consumers in ways never before possible—and in the process not only improve sales but also build lasting consumer-brand relationships. Advertisers need to adopt advanced tools. To use those tools, they will need to change some practices and address fragmentation and inefficiency. Advertisers have a lot to gain from fixing the system and realizing much of the promise that digital advertising holds.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following advertising agencies for their assistance with, and support of, the study: Audience on Demand UK, Essence, M2 Universal, and ZenithOptimedia UK. They also wish to acknowledge the assistance of the following BCG partners and colleagues: Mark Heath, Elias Baltassis, Julia Booth, Salvatore Cali, Guangying Hua, Jan Jamrich, Iman Karimi, John Keezell, and Olaf Rehse.