The U.S. education-publishing industry is undergoing a profound change. The shift to online learning is swiftly altering the competitive environment. Educators, students, parents, entrepreneurs, and politicians alike are looking for new ways to harness technology to improve student achievement, reduce costs, and deliver a more customized learning experience.

Meanwhile, a host of emerging companies are breaking down the boundaries between segments of the market in everything from curriculum and assessment to delivery and analytics, giving rise to potential new partners, competitors, and platforms. Publishers are vying with both traditional companies and online upstarts for a place in the digital ecosystem of education —not just the network of companies, individual contributors, institutions, and customers that interact to create mutual value, but also the technical platforms that allow devices, applications, data, products, and services to work together in new ways. (See “ The Age of Digital Ecosystems: Thriving in a World of Big Data ,” BCG article, July 2013.)

In this fast-changing environment, publishers face a once-in-a-decade chance to expand their share of the $1 trillion currently spent on education in the U.S. each year by adapting their existing offerings to the digital realm and expanding into markets opening up on the edges of their current business. A few publishers are well on their way on this journey, but most lag behind.

The Challenges Facing the Industry

Publishers were once protected from competition by high barriers to entry. They had the relationships with authors, knowledge of buying processes, and distribution clout to ensure their position—and their dominant market share. But their positions are now under attack as the business shifts toward digital content and away from a reliance on print textbooks. (See Exhibit 1.) The beneficiaries have been classroom-oriented testing companies and providers of practical tools that supplement core instruction, along with educational software and courseware builders, which have provided schools and colleges with greater flexibility in meeting varied learning needs.

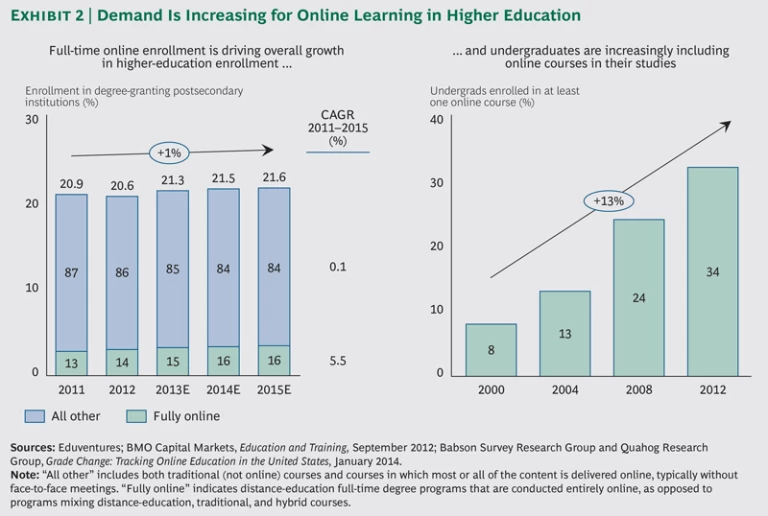

The world in which publishers operate is rapidly going digital. In U.S. higher education , online courses already account for about 14 percent of total enrollment. Nearly one-third of undergraduates took at least one online course in 2012, up from just one in ten in 2000. (See Exhibit 2.) Traditional universities, which long resisted online education, are now actively experimenting with digital platforms. The university systems of Maryland, Minnesota, and Texas either require or have proposed that anywhere from 10 to 25 percent of credits be earned through alternative modes such as online learning. Some universities have formed partnerships with operators in the “massively open online course” (MOOC) market, while others are offering or developing their own online degree programs. Meanwhile, an entire industry has sprouted up to help institutions expand their online programs.

K–12 education is moving more slowly but is also gaining momentum. About 4 percent of K–12 students are taking online courses, although less than 1 percent of total enrollment is in fully online programs.

In short, the position of traditional education publishers is under threat. These companies are built around scale-based business models and capabilities designed for competition in a learning environment dominated by the printed book. Three trends are demanding that they change.

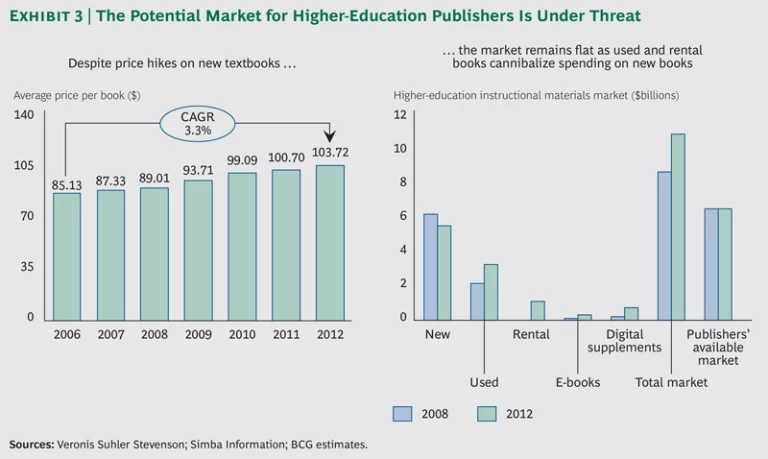

Digital distribution is undercutting print sales. From 2006 to 2011, price increases drove 3.3 percent annualized growth in higher-education revenue for new print textbooks. The ability to steadily raise prices demonstrates the pricing power associated with a consolidated industry in which purchasing options and price transparency were limited.

But all this has changed: used, rental, and e-book options, along with search and price discovery tools, are eating away at the new-book market. Alternatives to new textbooks, available through outlets such as Chegg and Amazon, are nearly half the price of print books sold at brick-and-mortar college bookstores. Most notably, book rentals have provided a lower-price alternative to used books, further eroding publishers’ share of spending on instructional materials. The result is that the potential market for publishers—when narrowly defined in terms of textbooks and digital supplements—is virtually flat compared with 2008 levels. (See Exhibit 3.)

While publishers hope to offset these declines by increasing digital sales, their strategy has relied heavily on bundling digital homework supplements with new textbooks at prices only moderately more than the standalone price of a new book. The rise of used and rental sales potentially undercuts this strategy. Without the sale of a new book, publishers must sell homework supplements on a standalone basis, which forces them to prove the value of the digital components and adds pressure to price supplements aggressively to compensate for the expected decline in sales of new textbooks. Publishers also face resistance from students, many of whom are not inclined to buy materials that their professors do not mandate.

Amid such developments, publishers must find additional ways to shore up their traditional revenues over the short to medium term. This will ensure that they have the resources to invest in business models that will secure long-term success in the evolving digital landscape.

New content sources are proliferating. Institutions, professors, and students are demanding high-quality, up-to-date content with digital capabilities. They are experimenting with dynamic multimedia formats, modular course design, and customized and adaptive learning. Competition for these users has arisen from a proliferation of operators, including the following:

- Open Educational Resource (OER) Providers. Organizations such as Khan Academy, BetterLesson, and Gooru offer increasingly sophisticated tools that enable teachers, students, and parents to find and customize high-quality resources at low or no cost. To date, publishers have largely been able to forestall this threat thanks to the “stickiness” of traditional content and the continuing perception of its superiority. For example, a recent survey of K–12 educators conducted by BCG for the Hewlett Foundation found that nearly half of those surveyed were not aware of OER, despite its presence on the scene for more than a decade. However, evidence suggests that this is changing. Of the K–12 educators who said they were aware of OER, 96 percent described themselves as “receptive” to it, and half expected to use more of these resources over the next three years.

-

Online-Courseware Creators. Organizations such as K12, Apex Learning, and Carnegie Mellon, as well as a range of MOOC providers, are producing their own courseware tailored to the digital environment. Besides incorporating multimedia resources, they are embedding educational assessments into their platforms, adapting the learning experience based on students’ needs, and producing rich analyses of student data.

Some leading MOOC providers are avoiding traditional textbooks in order to keep courses open and free. According to the website of MOOC provider Udacity, “There are no required textbooks for Udacity courses, and the course content does not follow any textbook.” When Udacity classes include readings, they link to supplemental texts embedded in the online course. In cases where MOOCs do recommend textbooks, the course development process often favors custom publishing. For example, a 2012 course from edX titled “Introduction to Computation and Programming Using Python” offered, for $24.99, an optional custom textbook written by the instructor. MOOCs will no doubt open up a new market of casual learners for publishers, but they also represent a potential substitute for publishers’ content. As more universities assess and recognize the value of MOOCs, the threat posed by these courses to traditional publishers will grow.

- “Digital Native” Publishers and Self-Publishing Operators. Companies such as Flat World Knowledge have lower cost structures and often more flexible delivery options than traditional publishers. They offer customization tools to “build your own textbook” from a variety of preexisting and newly created content. And they feature a number of formats to suit the needs and preferences of different learners, including PDF, traditional print, and audio.

So far, most publishers have responded to these new sources of competition by simply transferring their print content into a digital format, in some cases incorporating basic multimedia features. To succeed, they will need to fundamentally rethink their value propositions to take full advantage of the digital medium and consider the entire educational experience.

Sales and distribution are changing. Traditional publishers have historically employed a product-oriented selling process based on long-term relationships. In higher education, salespeople have typically focused on professors and department heads. In K–12, sales teams have worked closely with state- or district-level selection committees over the course of extended textbook-adoption cycles.

With the shift to digital, the buying process, sales channels, and stakeholders involved are evolving to reflect the new products and services being sold. In higher education, purchasing often involves department heads, CIOs, and provosts, since the choices made can affect the entire school. In addition, schools require significant resources to sustain multiyear contracts for content, licensed software, or hosted systems. The selling strategies and relationships of the past must therefore be updated, as must the skills and training of the sales force.

In K–12, instructional-material adoption at the state level is opening up to more varied formats, including digital, often giving districts greater leeway in how they allocate funding. This has added new decision-makers to the selection process, including CIOs who are weighing in on the choice of learning platforms and software. Selling skills common in adjacent industries, such as solution selling by vendors of enterprise resource planning to colleges and universities, will likely prove increasingly valuable.

Students, parents, and teachers are also increasing their role in purchasing decisions. They can choose from more options than in the past, including rental and used books, as well as the OER and self-publishing options discussed above. And they are growing more demanding about what they will and will not purchase and at what price. Companies such as Kno, BetterLesson, and Gooru are capitalizing on these shifts by marketing directly to students, teachers, and parents, bypassing traditional institutional sales channels.

The common thread among all these stakeholders is the desire for improved student achievement and outcomes. Successful publishers will take a more iterative, solutions-based approach to the sales process by partnering with others to develop digital content. They will also redefine their existing, editorially focused sales practices to emphasize an integrated digital offering that combines curriculum and testing in order to ensure higher rates of student success.

Pearson’s partnership with Arizona State University (ASU) demonstrates the power of using a solutions-based approach focused on improving student outcomes. Before the adoption of Pearson’s curriculum, which is powered by Knewton’s adaptive-learning platform, up to 15 percent of ASU freshmen were not ready for college-level math. In 2011, about 5,000 freshman took remedial-math courses using the Pearson-Knewton curriculum. Half of them completed the course a month early, while withdrawal rates dropped seven points and pass rates rose nine points.

Ultimately, smart publishers will focus on how their solutions can support and optimize student learning and achievements. They will see themselves as participants in the student outcomes business as well as in the publishing business.

Publishers’ Last Stand?

Many observers see these threats as the death knell for education publishing. And the industry is no doubt being challenged. The four leading publishers with a presence in the U.S. (Pearson Education, McGraw-Hill Education, Cengage Learning, and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) all face profit pressures and strong headwinds hampering growth.

Other observers have drawn comparisons with the music and news-media industries, which were upended by digital technologies. They say that consumers could eventually download only the textbook chapters they need or shift en masse to inexpensive OER, causing textbooks to go the way of compact discs, which were disaggregated through downloads of individual songs. From 2004 to 2011, sales of physical music media dropped 75 percent, leaving a $5 billion hole in total company revenues. Similarly, the news media saw a dramatic erosion of its advertising-revenue base, with a $25 billion decline in revenues in 2011 compared with 2000. (See Transforming Print Media , BCG Focus, December 2012.)

However, we think education publishing is different. The industry has several advantages that it can use to transform its operating model and the way it goes to market. Many of these skills, capabilities, and assets were underappreciated in the old world of publishing but have become extremely valuable in a data-driven digital learning environment.

- Instructional Design Skills. These capabilities are used to build pedagogically sound instructional programs and to assist authors in designing the learning objectives that students must achieve in order to master a subject area. In the coming digital learning ecosystem, editors are increasingly being transformed into instructional designers who create the learning plan that instructors bring to life.

- Testing Skills. Publishers have deep expertise in devising test questions and other means of assessing learning. Testing results offer valuable feedback to instructors, as well as rich data that can feed into emerging models requiring adaptive and competency-based instruction.

- Content Classification Systems. In the past, content was constructed in long strings of text. But in today’s digital world, content must often be broken up into pieces. So-called content taxonomies provide the rules—the DNA code, so to speak—by which chunks of content can be assembled into a digital learning module, searched for, and flexibly reassembled to meet a particular student’s needs. These systems can help in the design of “learning maps” that underpin the sequence and structure of instructional design and align content with a specific set of learning standards.

- Well-Organized Content. Publishers can apply their classification systems to tag content with keywords and assemble modular banks of reusable content. In effect, they have produced the interoperable raw materials that can be assembled, like pieces of a puzzle, into today’s next-generation digital products and services.

- A Deep Understanding of Teachers and Students. Publishers have in-house a great deal of expertise about how teaching actually happens in the real world, because staff are often former teachers and teacher trainers. This knowledge can inform the development of best practices to identify good teachers, as well as be applied to designing products that will work in the classroom.

- Powerful Institutional Relationships. Publishers have spent decades understanding the needs of decision makers at every level of K–12 and higher education. Their insights are invaluable in gaining access to customers for digital products and meeting their criteria for purchase.

These assets have significant value when adapted to the new learning ecosystem that is developing. Because the looming disruptions we have identified will not happen overnight, publishers have an opportunity to take advantage of existing cash flows to both strengthen these skills and partner with others in areas where new skills are needed to deliver next-generation learning solutions. The potential to use existing cash flows is particularly evident among higher-education publishers, whose EBITA margins have been attractive.

Four Pathways to the Future

Still, major strategic threats remain. Publishers cannot afford to sit on their heels. To thrive in the digital ecosystem of education, they need to make changes in their products, business models, and sales processes. Successful companies will take four key actions.

Realign Organizations and Workflows to Create Truly Digital-Native Content

Publishers should move from translating print textbooks into digital form to creating truly digital courses that take advantage of everything the medium has to offer. Rather than thinking in terms of e-textbooks, publishers need to develop “whole-course solutions” that deliver an entire class or instructional unit.

The most forward-thinking companies reimagine the entire content experience, rather than simply incorporating multimedia features into the traditional textbook. They build a “closed-loop instructional system”—a highly aligned set of educational objectives, standards, curricula, assessments, interventions, and professional-development tools. These systems embed tests throughout the online course, provide real-time data for professors and students, and enable customized interventions to improve student outcomes, among other features. In the process, they free up teachers’ time to focus on the problem areas of struggling students. (See Unleashing the Potential of Technology in Education , BCG report, August 2011.)

To develop such products, publishers will need to redesign their organizations and, most important, their workflows. No longer can the textbook, assessment, and technology divisions operate in silos. They need to work in interdisciplinary teams in order to bring the best of the company to bear in developing new learning systems and services. For example, testing units often have valuable skills in advanced statistics and classification systems that can be applied to developing adaptive-learning solutions that determine when students receive certain content and test questions depending on their answers to previous questions.

As publishers digitize their catalogues and create whole-course solutions rather than strictly textbooks, we see a compelling logic in favor of building courseware and delivery platforms that work across the entire landscape of K–16 education. For example, colleges across the country could purchase a generic economics 101 whole-course solution, rather than purchasing one of the dozens of competing textbooks currently in use. The for-profit sector is already constructing these kinds of platforms for online delivery. Community colleges would also be good candidates for licensed courseware solutions that either supplement lectures or deliver completely online courses.

While this development would appear to cannibalize publishers’ current textbook sales, it could also offer them an opportunity to strike revenue-sharing arrangements for a portion of the tuition charged for a course. We see a large market potential forming in instructional outsourcing, if the sector can effectively limit increases in instructional costs while helping to deliver improved outcomes.

Explore Strategic Growth Opportunities in Adjacent Markets

Successful transformations ultimately depend on establishing new sources of growth and profit that capitalize on a company’s strengths and assets. The disruption of the education ecosystem is creating several such opportunities, many of which have the potential to be more attractive than publishers’ existing business in terms of revenue per student. Success depends largely on the extent to which a publisher participates in shaping student outcomes. For example, instructional content produces greater revenues per student when delivered as a service, with the publisher participating in instruction, than when delivered as a static product.

Instructional materials today represent just over 1 percent of per student spending in K–12 and 2 percent of per student spending in higher education, while delivery (primarily in the form of instructor salaries) represents 37 and 28 percent, respectively. The potential revenues from an expansion into delivery are large. Publishers can also move into such emerging areas as online-program management, which supplies institutions with outsourced instructional design and other elements to further the expansion of their online-learning offerings.

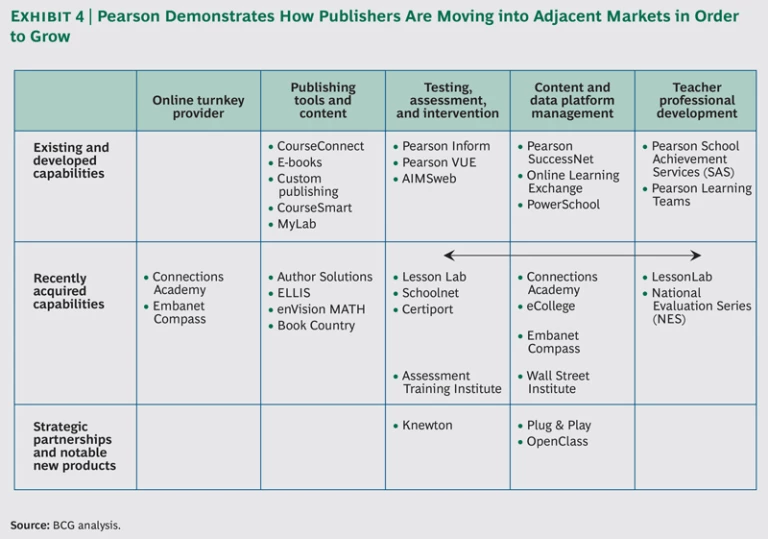

As shown in Exhibit 4, Pearson has adopted this growth strategy, extending its reach into services and operations through acquisitions such as the following:

- Schoolnet provides a K–12 learning platform for delivery of Pearson’s own content as well as curated third-party content.

- EmbanetCompass offers online-learning services.

- Wall Street Institute’s schools of English in China provide English-language learning.

- Connections Academy offers entry into the rapidly growing business of virtual charter schools.

A critical question for publishers to consider when moving into adjacent markets is whether they need to own the learning platform through which they distribute their content. Although it is still in a relatively early stage of development, the platform business is likely to remain diverse and fragmented for some time as competitors fight to amass a critical mass of users. The situation has been exacerbated by numerous closed options in which the content is homegrown, expensively curated, and bundled with the platform. For example, an estimated 2,200 of these “single-point solutions” are being piloted in the K–12 space alone, according to the One-to-One Institute.

Our view is that as IT and content standards develop, the market will increasingly address this fragmentation and eventually consolidate. So far, however, while personalized closed-loop learning systems are getting good results, their high cost, lack of distribution and marketing power, and difficulty providing schools with an integrated view of student performance make them difficult to scale. For now, publishers should consider platform providers as potential partners and new distribution channels, especially for digital content. Simultaneously, it is essential that publishers pilot new solutions in order to perfect the capabilities they will need later on.

At the same time that they move into adjacent markets, publishers must be wary of losing focus in their business-unit combinations or undervaluing their portfolio of assets. Companies often benefit when a parent company shares services and transfers best practices across business units. It can also be advantageous to lock up markets for the core business by creating linkages between units in areas such as curriculum and online-course design.

Revamp the Go-to-Market Model

Sales forces that once were organized around geography and product-based selling must now focus on distinct customer segments and solution-based sales models. They should emphasize frequent interaction and ongoing dialogue with institutions, professors, and students in order to understand their educational objectives, interpret data, and provide support.

This approach requires fundamentally different capabilities in developing learning objectives, delivering education, and assessing outcomes. In many cases, it will necessitate a shift in how institutions, professors, and students view publishers. Delivering outcomes, rather than selling textbooks, implies a very different sales model and a very different way of bringing resources to bear. (See “ Activating the Sales Force for Rapid Growth ,” BCG article, November 2012.)

While the print business must be rigorously managed for efficiency, digital ecosystems require an emphasis on speed, experimentation, and flexibility. In addition, goals and incentive structures for the sales organization must cascade down through the management ranks and be aligned with new objectives for selling digital products and engaging students, rather than just moving textbooks. Incentives should focus not only on selling publishers’ content but also on ensuring its use by students.

The universe of potential customers that publishers can serve is also expanding. Where education publishers used to regard colleges and universities as their primary customers, today they have to deal with a constellation of customers beyond traditional institutions. We are moving to a world of à la carte education where, instead of enrolling in a four-year degree program, students may cobble together a variety of courses and content from nontraditional providers at significantly lower cost. They can jump from institution to institution, stitching together modules of content to achieve truly personalized learning. As discussed earlier, nontraditional players, such as MOOC and OER providers, don’t necessarily rely on traditional textbooks. And students have far more say over the supplemental materials that they do or do not purchase. Publishers cannot afford to cede the MOOC space. They will need to consider how to make their content relevant in the new digital medium.

Professors, too, have many more choices in this environment, with a similar ability to piece together modular, interdisciplinary content from a variety of content providers and aggregators. Publishers that deal only with institutions may find themselves serving a shrinking market. Instead, they must stay relevant to the full range of providers, while leveraging their strengths in delivering pedagogically coherent, results-oriented content.

Maintain a Relentless Focus on Student Outcomes

Publishers cannot focus strictly on producing content; they must also measure its contribution to student learning and adapt their products in order to improve results. Strong results can come from enabling adaptive learning, providing modular content, assessing progress, boosting skills, and fostering credentials. Publishers have an opportunity to bring all these pieces together with data demonstrating continuous improvement and better outcomes. (See Unleashing the Potential of Technology in Education , BCG report, August 2011.)

Compared with traditional textbooks, digital products and content provide far richer data, allowing publishers to improve their products on the basis of what is and isn’t working. This is the source of their competitive advantage—the scale to invest in research that produces real academic results.

How to Get Started

To navigate the digital ecosystem of education publishing, senior executives should begin by asking themselves these questions:

- How can we take advantage of digital technologies to develop solutions that support superior student achievement and outcomes?

How can we create deeper relationships with institutions, professors, and students so that we can better support their goals? - How can we integrate elements of the digital education ecosystem, such as assessments and outcomes data, into our products to create closed-loop solutions?

- Which elements of the closed loop should we acquire or build ourselves, and which should we provide through partnerships?

- What new capabilities do we need in order to collaborate and compete effectively with digital-native providers, such as speed to market, business model flexibility, and improved knowledge of emerging deal structures?

- How can we adapt to new content-delivery models to ensure that our solutions are available when, where, and how institutions, professors, and students want them?

- How much distance from the core business do we want so that experiments can flourish?

As education publishers approach these issues, they must keep in mind that transformation is a difficult journey. The road to digital requires that they take a comprehensive look at their products, operating models, incentive structures, and other central elements of the business.

Publishing companies are leaving behind a business that was predictable. The market will increasingly reward those that shape the emerging learning ecosystem by creating new operating models and adapting their focus. In this environment of disruption and heightened competition, adaptation, flexibility, and experimentation will reign.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the insights and assistance of the following colleagues: Matt Claise, Dominic Field, Karen Gordon, Larry Kamener, Mirosia Martin, Lane McBride, J. Puckett, Vikas Taneja, Jo Wilson, and Paul Zwillenberg. They would also like to thank Mickey Butts for his assistance in shaping and writing this report, as well as Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Kim Friedman, Gina Goldstein, and Sara Strassenreiter for editing, design, and production.