If one had to choose a single word to describe the M&A market in 2013, it would be disappointing, and indeed many market participants have used this very term. But the exasperated dealmakers have had little time to cry in their beer—they’ve been too busy. The M&A market took off like a rocket in 2014, fueled by the return of the megadeal (transactions with a value of more than $10 billion), which has been in hibernation for the last several years. The momentum of the first quarter carried into the second, setting up 2014 as a potential bellwether for the market’s longer-term evolution.

Megadeals capture the headlines, adding confidence to the market. At the same time, there is another, less publicized but no less significant, trend developing—one that should attract even greater interest in the boardroom. As we first noted two years ago, our research shows a continuing rise in divestitures as a powerful strategy for both unlocking value in today’s markets and improving performance by focusing on core operations. (See Plant and Prune: How M&A Can Grow Portfolio Value , BCG report, September 2012.) In 2013, divestitures represented almost half the total M&A market. Not all divestitures are created equal or produce equivalent results, however. The companion to this year’s M&A report—the tenth in our series highlighting major trends and their implications for companies—examines in depth the role of an active divestiture strategy in companies’ ongoing search for value.

2013: Hopes Unrealized; 2014: Hopes Heightened

Is the long post-2008 M&A hangover finally coming to an end? Positive signs abound, for a change, starting with strong market activity . The Boston Consulting Group’s tenth annual assessment of crucial M&A trends, based on BCG’s global M&A database of almost 40,000 transactions since 1990, shows that following an anemic 2011 and a slow 2012, the M&A market stabilized in 2013, albeit at disappointing levels. It entered 2014 with a strong tailwind, including the announcement of roughly as many megadeals in the first six months as in the two previous years combined.

Multiple factors are fueling the resurgence. Continued low interest rates, the ample availability of capital, a less uncertain economic outlook, and high levels of M&A interest and financial capability on the part of both corporations and private-equity firms all bode well for the future. In addition, continuing a trend begun a few years ago, corporate divestitures are taking a growing share of the overall M&A market. (See Creating Shareholder Value with Divestitures , BCG article, September 2014.)

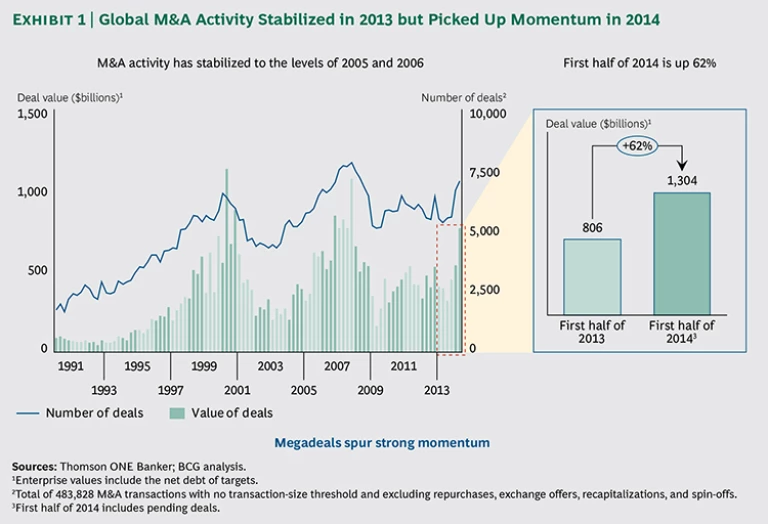

After furrowing a deep trough in the years following 2008, the M&A market has at last recovered to the levels of 2005 and 2006. That said, most market participants saw 2013 as a disappointment. Overall deal volume declined by 6 percent and total deal value fell by 10 percent from 2012—despite credit remaining cheap, corporate profits continuing to rise, and generally strong performance by global equity markets. (See Exhibit 1.)

Multiple culprits can be identified. Most significantly, the much-awaited economic recovery failed to materialize, and neither employment levels nor consumer confidence improved as expected. GDP growth disappointed just about everywhere, especially in Europe, and many companies also held back from pursuing big or aggressive transactions owing to the continuing economic uncertainty. Deal volume and value fell in the financial-services and metals-and-mining sectors after heightened activity in the preceding years. Activity in Japan and a number of emerging markets, especially Brazil, Russia, and India, also declined. As is the case every year, several hundred transactions were announced but failed to reach consummation. The number of uncompleted deals was roughly equal in 2013 and 2012, but the total value of the withdrawn deals in 2013 was bigger as several large transactions were canceled, including the acquisition of 70 percent of Koninklijke KPN by América Móvil for $10 billion and the sale of BlackBerry to Fairfax Financial Holdings for $5 billion.

How quickly sentiments—and outlook—can change, however. The total value of first-half 2014 transactions jumped 62 percent over the value of transactions in the first six months of 2013. Megadeals accounted for more than 35 percent of total first-half 2014 deal value, including five deals worth more than $43 billion each—a level of activity not witnessed since before the financial crisis. These types of transactions not only boost the statistics, they also transform the confidence level of the market. Dealmakers who have been sitting on the sidelines, uncertain about financing, investor reaction, regulatory approvals, or other factors, see industry-altering transactions in the works and start to believe their deals can get done. Indeed, the hot pace continued into the second quarter, with AT&T’s acquisition of Directv, Apple’s acquisition of Beats Electronics, the $50 billion merger of cement makers Lafarge and Holcim, and the heated competition to acquire Alstom’s energy-equipment assets, which General Electric appears poised to win.

The overall economic outlook is the most positive in years, with U.S. GDP growth projected to approach 3 percent as we move into 2015, and growth expected to return to Europe, albeit slowly. Equity markets are holding up thus far, through the end of the second quarter. As always, there are risks that political or international events—in the Middle East and Ukraine, for example—could have a negative impact on the economy and thus on deal activity.

North America Leads the Comeback—Fueled by High Tech

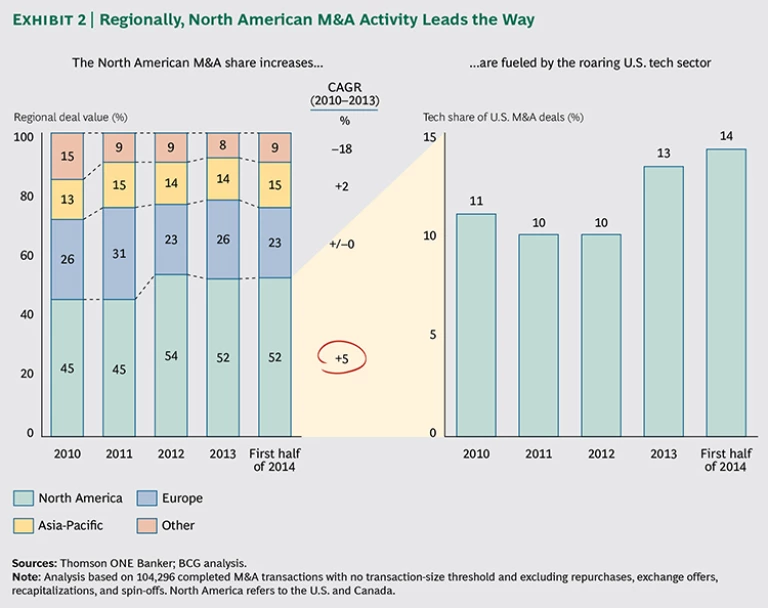

The global M&A market is led by North America, whose share has been on the rise and reached 52 percent in the first half of 2014—up from 45 percent in 2010. While M&A activity stagnated or even decreased in most regions of the world, total deal value in the U.S. and Canada rose more than 5 percent per year over this period. The roaring tech sector has been a driving force, since the most prominent players in high-tech M&A are based in the U.S. (See Exhibit 2.)

Rather than following an overarching industry trend, many tech deals are rooted in individual company needs—Apple’s acquisition of Beats to rejuvenate its music business, for example. With the acquisitions of Oculus VR and Nest Labs, respectively, Facebook and Google are looking to stay at the cutting edge of technological advances with strong consumer applications, as innovations such as augmented reality and machine-to-machine communications begin to gain market traction. Priceline.com’s purchase of online restaurant-reservation service OpenTable (for $2.7 billion) promises the potential of cross-marketing to different digital consumer segments.

The rapid rise of mobile as the world’s dominant communications technology is spurring M&A activity in several spheres. Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp and Verizon’s $130 billion acquisition of Vodafone’s interest in Verizon Wireless show companies expanding, or consolidating control of, their share of mobile users. Microsoft is gaining control over mobile technology with its acquisition of Nokia’s device-and-service business.

Not all the tech activity is in North America. Dozens of deals have been announced involving European countries in late 2013 and the first half of 2014. However, since many of them represent smaller transactions, their overall impact on M&A markets has been less visible.

Outside the tech sector, so-called inversion deals are becoming an increasingly significant factor, particularly in the health care industry. U.S. companies are seeking acquisitions in Europe that make strategic sense and enable the acquirer to move its corporate domicile to Europe, where the company will benefit from more favorable tax treatment. In July, the Wall Street Journal estimated that almost a dozen such deals were pending, with a total value exceeding $100 billion.

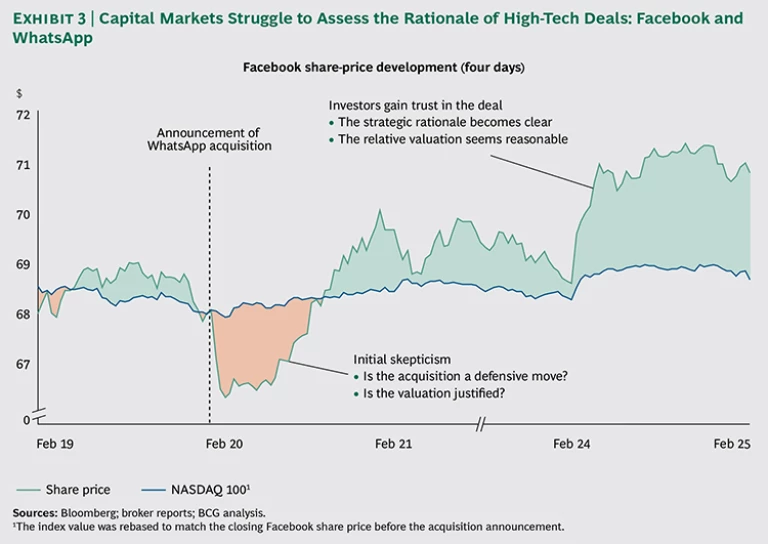

Despite a rising number of transactions, capital markets continue to have difficulty deciphering the new business models of innovative tech companies and coming to grips with the seemingly outsize valuations that acquirers place on their targets, which often have limited track records and little or no earnings history. Memories of the bursting dot-com bubble in 2000 are still fairly fresh.

The February 2014 announcement of Facebook’s plan to acquire WhatsApp, a five-year-old cross-platform instant-messaging service with 55 employees, for $19 billion in cash and stock is a case in point—especially since WhatsApp had only recently completed a round of venture-capital funding that valued the company at $1.5 billion. Immediately after Facebook announced the acquisition, its share price dropped 5 percent because of skepticism over the deal and the company’s rationale. It took several days—and a concerted investor-outreach effort—for investors to understand the basis for the deal, both strategic and financial. The market ultimately awarded Facebook a cumulative abnormal return (CAR) of 1.1 percent. (CAR assesses a deal’s impact by measuring the

Will the Pace Pick Up?

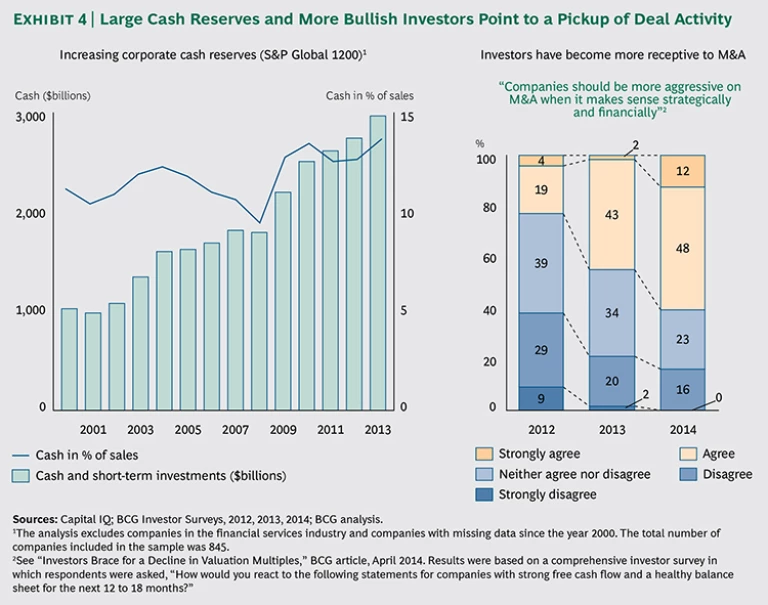

Multiple factors—principal among them large cash reserves, bullish investors, and buoyant debt markets—point to a continued resurgence in deal activity.

Corporate cash reserves have been increasing since the financial crisis. Countless companies have used the downturn to strengthen their balance sheets and improve their performance, giving them a much-enhanced means of financing acquisitions. Corporate cash levels are at an all-time high—three times their level in 2000. Shareholders become restless with so much money sitting idly on the sidelines, and they will eventually demand that companies either put the money to work or distribute it to their owners through share buybacks or dividends, especially as the uncertainty in capital markets recedes. As economic conditions improve, investors are becoming far more receptive to companies making acquisitions so long as the deals are consistent with their strategy and, of course, the price is seen as reasonable. In BCG’s 2014 investor survey, the percentage of respondents favoring a more aggressive approach to M&A by companies almost tripled, from 23 percent to 60 percent, between 2012 and 2014. (See Exhibit 4.)

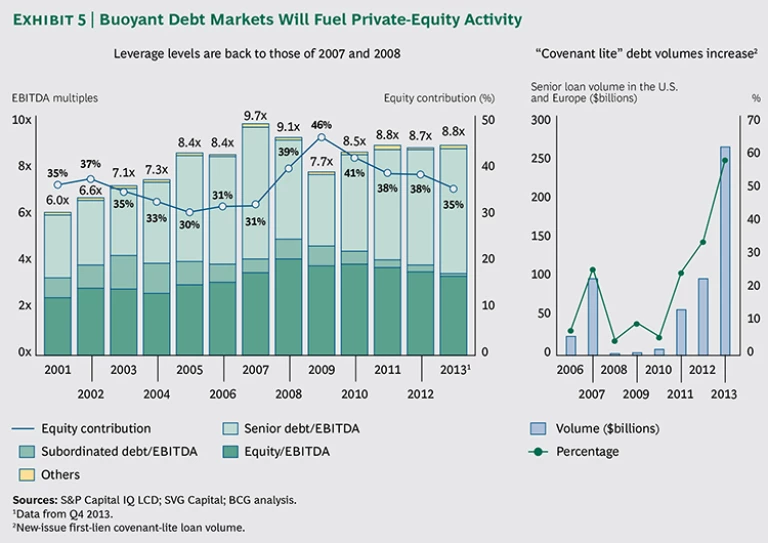

While activity among private-equity players has increased only slightly so far—the number of transactions rose 22 percent between 2012 and 2013, but the total value actually declined 3 percent—we do not see these firms remaining quiet for long. At a total of $431 billion, private-equity cash reserves are approaching their levels in 2008 and 2009, and these firms have their own investors to answer to. Moreover, debt financing is more readily available now than at any time in recent years. Leverage levels have returned to those of 2007 and 2008. (See Exhibit 5.) The average deal in 2013 included only 35 percent equity. “Covenant lite” loan activity in 2013 also smashed all records. The incidence of these loans, which generally do not involve any maintenance covenants, indicates growing investor appetite in the leveraged-loan market, making borrowing even more attractive for private-equity deals. We expect private-equity firms to become much more active in all kinds of transactions, with the exception of the largest megadeals, which are simply beyond their reach, if not their comfort zone.

Last but hardly far from least, current transaction valuations are still within long-term historical parameters. Valuation levels (as measured by the ratio of median acquisition enterprise value to EBITDA—EV/EBITDA) have been generally (if unevenly) rising since 2008, and they surpassed the historical average of 11.9 in the first half of 2014. Deal premiums (the amount by which the offer price exceeds the target company’s closing stock price one week before the original announcement date) approximated their historical average of 35.4 percent in 2013. One could thus argue that targets are not yet overvalued from a historical perspective—one more reason why deal activity among both corporate and private-equity players should continue to increase.

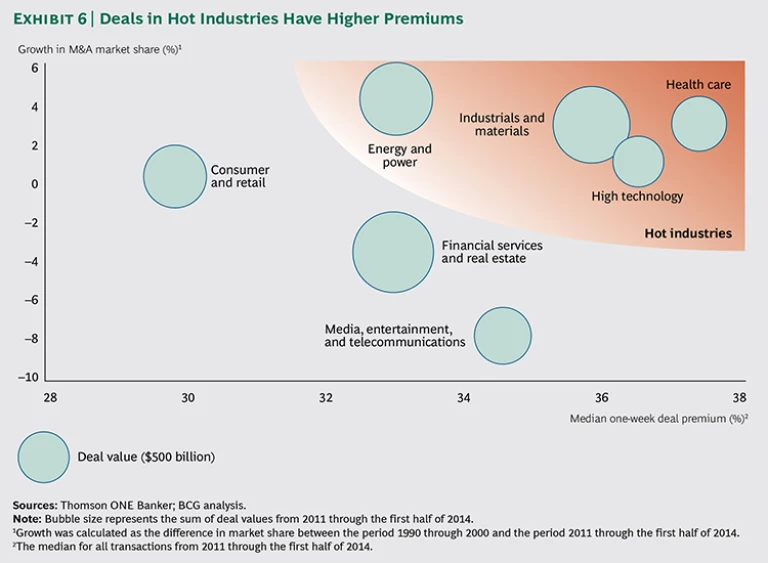

That said, it should also be noted that some industries are distinctly more active than others. Our analysis of deal volume (measured by transaction value) shows clear sector differences when long-term historical activity (from 1990 through 2010) is compared with deals done since 2011.

Energy, for example, saw a 4-percentage-point uptick in the current period, owing primarily to portfolio restructurings and consolidation, as well as to an increased focus on renewable energies following the Fukushima accident. Higher levels of activity in the health care sector (up 3 percentage points) are substantially the result of pharmaceutical companies acquiring new research pipelines as their own R&D programs produce fewer blockbusters and the patents covering older top-selling drugs expire. Changes in health care regulations in the U.S. and a difficult environment in Europe are also fueling consolidation in the sector. Companies in the industrial sector have been optimizing their portfolios as economies stabilize and return to growth. And, of course, high tech is highly active.

There is a clear impact of M&A intensity in “hot” industries: target companies are able to demand higher premiums from potential buyers. (See Exhibit 6.) Companies acquired in high tech and health care, for example, received average premiums of 36.5 percent and 37.3 percent, respectively, compared with premiums of only 29.9 percent in consumer and retail and 33.0 percent in financial services and real estate.

Timing is not everything in M&A, but it almost always is a critical factor and certainly an important consideration for both buyers and sellers during upswings in their industries.