Most corporate-executive suites are packed with all manner of state-of-the-art technology. But one low-tech instrument is in demand in nearly all of them: a periscope. Not a literal one, perhaps, but CEOs would no doubt welcome the ability to see around corners and spot the approaching forces that could disrupt their businesses or give them an innovation advantage over their peers. In this report, The Boston Consulting Group takes a close look at tools already in use at some of the corporate world’s innovation leaders to identify and explore new pathways to growth, including business incubators and accelerators, corporate venture investing, and strategic partnerships. Drawing on our extensive experience in the field, we offer insights into their most effective applications and describe how they can best be used in concert for maximum strategic advantage.

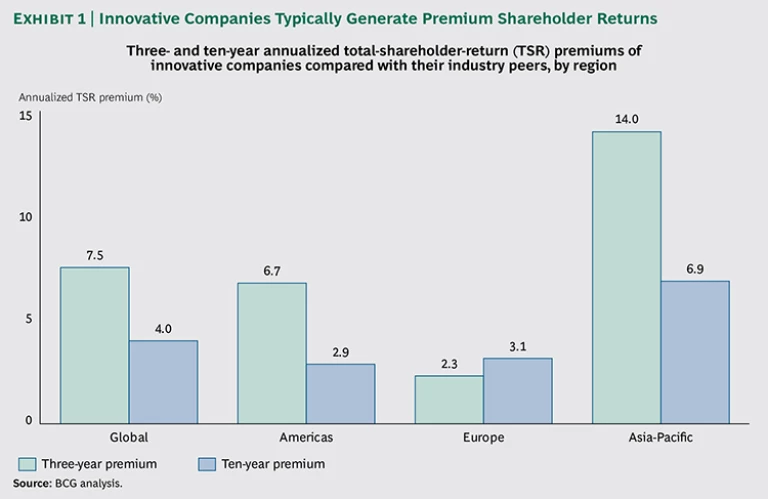

Innovation is high on most CEOs’ agendas—some 77 percent of those we surveyed in 2013 said it was their top strategic priority or one of their top three priorities. (See “Looking Back at Lessons from Leaders: The Most Innovative Companies 2013.”) Corporate leaders are urgently concerned about innovation for one simple reason: growth through innovation is the surest, straightest route to superior performance. In the Americas, for example, innovative companies generate three-year total shareholder return premiums of 6.7 percent over their industry peers; the ten-year premium is 2.9 percent. The spread is even wider in Asia, where innovators enjoy a 14 percent three-year premium and a 6.9 percent ten-year premium over their peers. (See Exhibit 1.)

LOOKING BACK AT "LESSONS FROM LEADERS: THE MOST INNOVATIVE COMPANIES 2013"

The aim of BCG’s report Lessons from Leaders: The Most Innovative Companies 2013 was straightforward: to identify and analyze what gives successful innovators their edge in performance, growth, and shareholder returns. After extensive analysis and interviews with the leaders of innovative companies, we identified five key success factors that differentiate the most innovative organizations from the rest of the pack:

- The Commitment of Senior Management. The report cites examples of CEOs and other corporate leaders who spearheaded their companies’ innovation efforts, instituting “fundamental changes in corporate culture, systems, and practices” in order to promote innovation throughout the organization.

- The Ability to Leverage Intellectual Property (IP). The most innovative companies do more than defend their most valuable ideas. They use their IP to establish competitive advantage, regularly culling their patent portfolios, structuring their organizations in order to incorporate IP considerations at every step of the product development process, and generating incremental revenues by selling and licensing IP.

- Strong Management of the IP Portfolio. The most consistent innovators actively manage their mix of incremental and “new to the world” innovations and have in place rigorous processes for identifying and promoting high-potential projects—and for halting them if and when their promise fades.

- A Customer Focus. The most highly regarded innovators recognize that innovation does not occur in a vacuum. They constantly interact with their customers. This helps ensure demand for their products at the time of market entry, deepens their relationship with their customers, and prevents them from overspecifying or overengineering products beyond what customers need or are willing to pay.

- Well-Defined and Well-Governed Processes. The most consistently successful innovators have strong processes for reviewing projects in development and ensuring their timely completion. They use transparent criteria as the basis for decisions; draw clear distinctions among governance, portfolio management, and project management; and recognize the importance of being effective along all three dimensions.

Not every company that embodies the five attributes just described will enjoy a long run as a leading innovator. But such organizations are the ones that are most likely to ingrain innovation as part of their corporate makeup. There is no surer formula for lasting advantage, sustained growth, and corporate longevity.

Those premiums reflect the centrality of innovation in today’s environment. In search of game-changing new ideas, many companies are broadening their quest for growth-driving innovation beyond their internal R&D efforts and M&A activities. These additional activities and tools can yield sizable strategic and financial benefits and expose companies to a wider range of new ideas than they could generate internally.

An Inventory of the Innovator’s Tool Kit

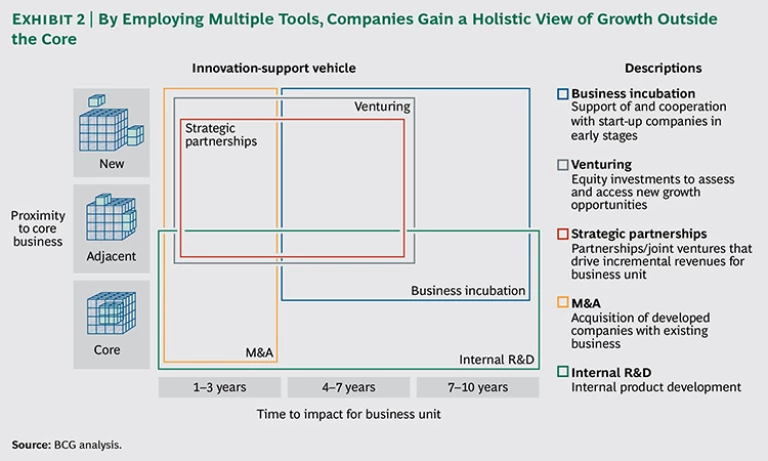

Used in concert, the innovation discovery tools that we identified enable companies to take a holistic view of growth that encompasses core, adjacent, and noncore activities; that accommodates diverse methods of collaboration and start-up support; and that allows for different rates of development in different spheres. (See Exhibit 2.) Some forward-looking companies are already using all or some of this suite of tools to gain an edge in today’s hypercompetitive environment. Energy companies are experimenting with new business models in the new renewable-energy field. Automotive companies are expanding their product portfolios and broadening their ecosystems through investments in mobility systems and new financing models. Pharmaceutical companies are branching into new business areas such as nutrition products. In each case, companies are leveraging their business-incubation, venturing, and partnership activities to widen their search fields and find innovations in corners of the business world that they had not previously explored.

When correctly applied, these tools enable companies to engage with other organizations in various stages of development, from start-ups still in product development to companies in their early growth stages to mature enterprises. They also enable companies to commit to a range of time horizons with varying levels of financial investment.

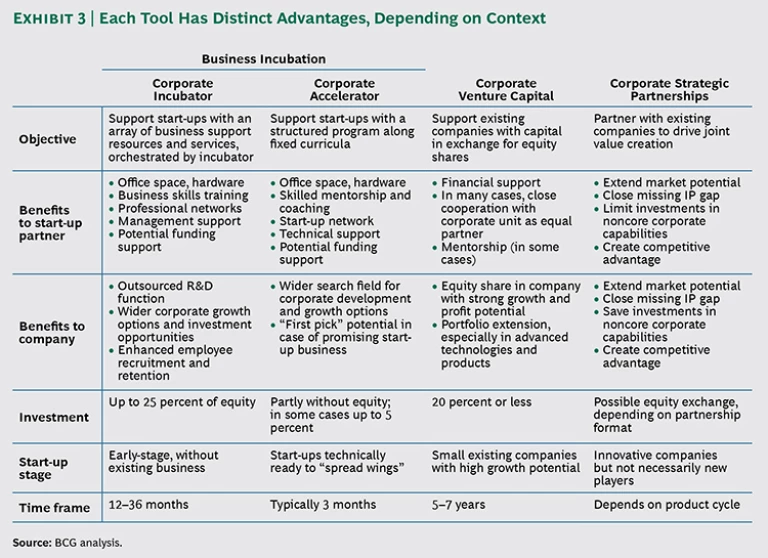

Below, we analyze each innovation tool and describe how innovation leaders in six industries—automotive, chemical, consumer goods, media and publishing, technology, and telecommunications—apply them to maximize their innovation capabilities. (See Exhibit 3.)

Catch Early-Stage Innovation with Incubators and Accelerators

In the quest for innovation, many companies have recently raised their game by means of incubators and accelerators. These tools allow them to engage with early-stage start-ups either over a relatively lengthy period of intensive business development or through a shorter-term structured curriculum. In this respect, they differ from venture investing, which focuses on more mature start-ups, and from strategic partnerships, which facilitate the rapid introduction of new products or services leveraging mature technology.

Incubators enable companies to support and collaborate with a handful of promising start-ups for as long as three years. Sponsoring companies make equity investments of as much as 25 percent and afford the start-ups access to corporate resources and facilities. The start-ups selected for incubation have significant interactions with their corporate sponsor, at both the corporate and business-unit levels.

Accelerators, in contrast, enable rapid screening of a large number of start-ups focused on a particular technology or region. Support takes the form of a structured business-development curriculum for a fixed term (typically, three months). The start-ups invited to participate in the accelerator are usually on the verge of launching revenue-generating activities, and the corporate sponsor promotes their development by granting them access to office space, technical support, high-quality mentoring, networks of other start-ups, and funding sources. In return, the company gains early access to promising ideas and companies. The corporate sponsor typically makes no equity investment in the start-ups, and interaction at the corporate and business-unit level is limited. Some companies, though, will take small equity stakes (5 percent or less) to lock in access to an especially promising venture.

How Companies Are Using Incubators and Accelerators

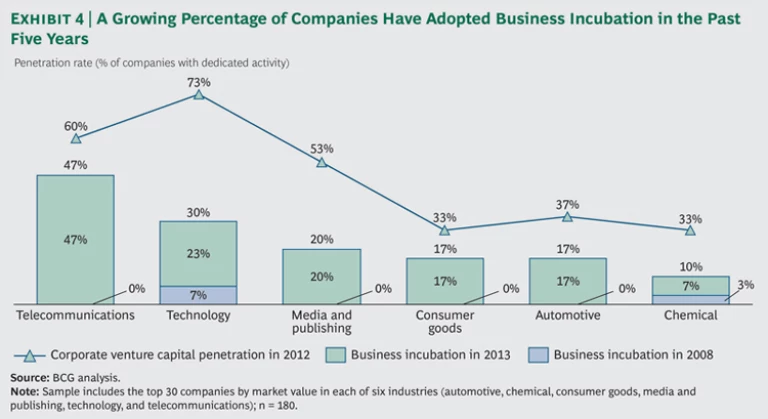

BCG analyzed the top 30 companies (as measured by market value) in each of the six innovation-intensive industries singled out for close study. (See Exhibit 4.) We found them to be among the early adopters of both tools, with 19 of the 180 companies establishing incubators or accelerators in 2013 alone. In all six industries, 43 percent of the top 10 companies have established incubators or accelerators, compared with 23 percent of the top 30.

Many of these companies have opted to locate their incubators and accelerators in one of four widely recognized innovation hot spots: Silicon Valley, Berlin, London, and Tel Aviv.

Others, though, concentrate their incubation and acceleration activities near their corporate R&D units or near or within certain target markets. This strategy is especially common among telecommunications, publishing, and technology companies, although some players in those industries prefer the big-four innovation hot spots.

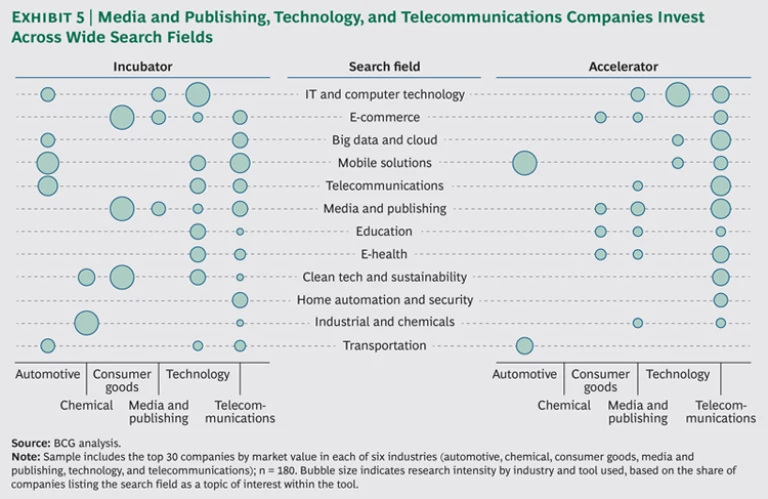

Companies focus their search for innovation on different industries and targets, in alignment with their overall business strategies. Although telecommunications, technology, and media and publishing companies target and invest in a wide range of start-up companies, for example, automotive companies generally restrict their searches and investments to mobile solutions and innovative transportation support. (See Exhibit 5.) E-commerce and media and publishing start-ups draw investment funding from telecommunications, technology, media and publishing, and consumer goods companies, whereas telecommunications players dominate the field of home automation and security.

Chemical companies are a case apart. In general, they favor incubators over accelerators, because the time horizons associated with incubation align more naturally with the industry’s long and costly product-development cycles. Most chemical companies locate their incubators near their own R&D infrastructure to facilitate access to corporate labs and testing facilities. When a start-up in the incubator develops a marketable product or service, the corporate sponsor usually steps in to provide the resources needed to scale up.

Which Tool? It Depends on the Need

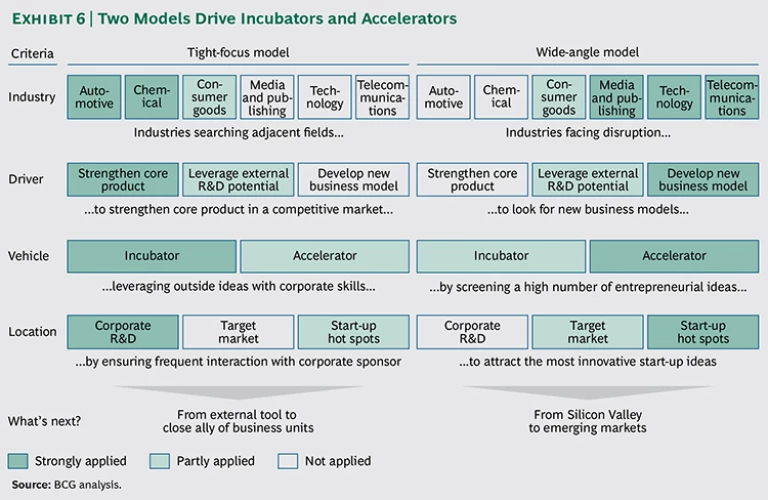

Analysis of companies active in accelerators and incubators shows that they generally employ one of two models, referred to here as the tight-focus and wide-angle models. (See Exhibit 6.)

The tight-focus model is designed to strengthen the core business of the company sponsoring the incubator or accelerator. Often targeting innovations in business adjacencies as well as the core itself, the incubator or accelerator is located in physical proximity to corporate R&D facilities to promote cooperation between the R&D and incubation units.

Most companies that follow the tight-focus model opt for incubators rather than accelerators because the comparatively large equity investments involved in incubation promote especially close cooperation between the sponsoring company and the selected start-ups. The tight-focus model is employed by automotive, chemical, and some consumer goods companies because their competitive environments demand that they continually come up with better versions of their core products.

Accelerators, in contrast, emphasize the transfer of expertise and best practices, rather than cash, to promote business development. Companies that are seeking innovation of any kind, regardless of its proximity to the core business, generally opt for this tool and follow the wide-angle model, which is designed to capture new thinking across a broad spread of domains, especially mobile solutions, IT, and Internet-based solutions. To give themselves access to a variety of innovations in a short amount of time, companies generally locate their incubators in one of the four start-up hot spots. Technology, media and publishing, telecommunications, and some consumer goods companies often employ the wide-angle model because their industries are fast-changing, and disruption can come from virtually any direction. They therefore cast as wide a net as possible.

Companies need to keep several success factors firmly in mind when setting up a business incubator or accelerator. As with any large-scale corporate initiative, such programs need senior leadership’s visible, active backing and continuing engagement. The objectives of incubation and acceleration programs should be fully and clearly defined and documented, as should the company’s path to harvesting and commercializing outside innovation.

Strengthen the Corporate Core with Venture Investing

The most promising alumni of an incubator or accelerator are often targeted for investment by the sponsoring company’s venture-capital unit. Such units are typically the cornerstone of any corporate effort to access outside innovation. Of the 42 companies in our analytical sample that have formal business-incubation programs, 39 also have corporate venture-capital units. In most cases, companies first develop venture units, then proceed to build from there, installing incubation or acceleration units to complement their venturing activities.

In recent years, many companies have turned to venture investing to locate and acquire innovation in areas adjacent to their core businesses. (See “Looking Back at Corporate Venture Capital: Avoid the Risk, Miss the Rewards.”) Today, almost 50 percent of the top 30 companies (as measured by market capitalization) in our sample of six innovation-driven industries are actively engaged in venture investing, and companies in industries across the board have stepped up their investing markedly or entered the arena for the first time.

LOOKING BACK AT "CORPORATE VENTURE CAPITAL: AVOID THE RISK, MISS THE REWARDS"

BCG’s 2012 publication Corporate Venture Capital: Avoid the Risk, Miss the Rewards made the case that venture investing, once the fringe activity of a handful of players in a few industries, has taken root across the corporate landscape. In industries with a long history of venture investing, such as pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, and technology, more than half of the 30 largest companies have venture-investing units in place.

Once prone to boom-and-bust cycles, corporate venture units are lasting longer, investing more, and, increasingly, co-investing across industry lines. Recognizing the competitive advantage that innovation confers—and wary of missing out on a disruptive innovation that could render their current business models obsolete—companies are establishing venture business units at an ever-accelerating clip, and industries that formerly ignored the venture-investing world are jumping into the game and scrambling to catch up.

Industrial companies, for example, are spreading their investments widely but maintaining a strong focus on related industries, committing capital to clean technology, information technology, and health care. Increasingly, their investments, once largely confined to the U.S., are heading offshore.

The report identifies the ground rules followed by the most successful corporate venture operations:

They have the full backing of senior corporate management, which is actively involved in designing the venture unit, formulating investment strategy, and implementing processes to capture the full strategic and financial value of their investments.

The strategies of the venture units are tightly aligned with the parent company’s overall business and innovation strategy, and ideas gleaned from venture investments flow by well-marked routes into the larger corporate innovation pipeline.

Exemplary corporate venturing units also have clear and consistent investment parameters, with well-defined search fields and risk tolerances, and they accept the occasional failed investment as inevitable.

Most of all, the best corporate venture units, as well as the leaders who guide them, understand that greater than the risk of failure is the risk of not investing at all.

The objectives of corporate venture investing have shifted in recent years. As companies have gained venturing experience and sophistication, best-in-class venturing units have concentrated on accelerating the growth of their start-ups and their own business units. Following from this change in focus, best-in-class venture units now establish clear guidelines that spell out the strategic needs of the business units and align venture search fields and targets with those needs. The search fields focus on areas where one or more of the business units can offer a start-up a competitive edge and a value creation plan.

That plan follows a clearly delineated logic, typically centered on one of four value- creation models that vary with the maturity of the start-up:

- Under the first model, the start-up and venture capital unit jointly establish proof of concept. That entails testing and confirming not just the technical feasibility of producing a product but also the ability to create a robust supply chain and to recover capital investments, among other considerations.

- The second model involves the development of a robust business plan. The corporate investor trains a business lens on a start-up’s technology or product and identifies a sustainable business model to monetize it.

- Under the third model, the venture investment creates value by accelerating or deepening a start-up’s market penetration. The investment speeds product development by reducing production time and cost while improving quality.

- The fourth model creates value by accelerating the commercialization of a product or products through, for example, supplier agreements with the host business units of the corporate investor. The objective of the investment is to increase the speed and depth of the market penetration of the start-up’s products.

Whatever the underlying model, the company needs to ensure that the value of the partnership is clear to the start-up and that the right people are involved at the right time in the process. It’s equally important to track business milestones through rigorous KPI reporting and to ensure transparency through regular internal and external communication with the start-up and within the company.

Strategic Partnerships Answer the Need for Speed

Companies seeking short-term product development, commercialization, and rollout of outside innovations typically opt for strategic partnerships with already established start-up companies. The typical strategic partnership involves creating a new legal entity to hold the partnership’s assets and oversee operations. The corporate partner’s typical investment is in the $10 million to $50 million range, usually financed with some combination of equity and debt. In some cases, the deal is funded by external investment. The start-up partner is usually a late-stage, revenue-generating company.

Because financial rather than strategic concerns motivate most partnerships, companies entering into these arrangements should clearly define their financial expectations, such as 12- to 18-month revenue goals, return-on-capital benchmarks, and a firm timetable for recovery of all invested capital.

A growing number of large companies are forming strategic partnerships to close knowledge gaps and drive value creation for both partners. Such arrangements enable companies to leverage the assets of other companies in order to drive near-term commercial growth. Through partnerships, companies can address new customer populations, expand the market for existing or contemplated products, share distribution or sales channels, and fine-tune new business models.

When executed effectively, strategic partnerships enable each partner to expand or more deeply penetrate its market with products or services that complement its own product portfolio, without having to invest in noncore activities. Partnerships are especially valuable to companies seeking quick entry to a particular market or business line because of technological disruption, new market entrants, or aggressive moves by competitors.

Appropriate governance structures are crucial to any partnership’s success. The deal should spell out in detail the roles, responsibilities, and obligations of each partner and identify the business units on each side that will be accountable for the partnership’s operations and results. Partners are typically active owners, governing through either majority control or, in the case of minority shareholders, a board seat. Exit transactions usually involve either public offerings of shares in the partnership or the buyout of one partner and the subsequent integration of the partnership’s financial results into the acquirer’s books.

Several factors are key to the success of strategic partnerships. Most activities should take place at the business unit level, with one unit driving the choice of partner and taking responsibility for the partnership’s performance. Business unit leaders should be able to clearly articulate how the partnership will generate a tangible benefit—in the form of improved customer satisfaction, new-customer adoption, or higher revenues—within one year. And the deal should grant the company exclusive access to the partner’s product or service for a period long enough to give it a competitive advantage.

Fine-Tuning Performance

Five success factors distinguish high-functioning suites of innovation discovery tools from less effective ones:

- Close strategic alignment with the company and relevant business unit

- True partnership between newer innovation tools and corporate R&D, M&A, and individual business units

- Strong company backing in good times and bad

- Effective organization design

- Effective leadership and the right mix of personnel

Strategic Alignment

We have observed that the design and use of innovation tools at best-in-class companies are closely aligned with overall corporate and business-unit strategy. This alignment is apparent in the goals of the innovation search and the fields on which the search is focused. Thus, if the company is seeking outside innovation close to the core over the medium term, venture investments are probably the most suitable tool. If it seeks a specific product or technology that is still under development, an incubator (using the tight-focus model) is likely the best tool for the job. If it’s looking to take the pulse of the entrepreneurial sector, an accelerator can provide a relatively rapid overview. And if it needs to roll out a specific product or service within a narrow window of opportunity (whether to harness a potentially disruptive force or to recover ground lost to rivals), partnerships are the most suitable tool.

Companies should also assess which innovation support capabilities they should build up in-house and which they should “rent”—for example, by partnering with an existing accelerator program. The further the innovation is from the corporate core, the more carefully the company needs to consider whether its capabilities and culture can successfully support activities that require a significant investment in expertise, management time, and oversight. The full suite of innovation tools is not always needed. Instead, companies should carefully assess each tool’s relevance to their business and its capacity to contribute to strategic goals.

True Partnership Between Internal and External Innovation Centers

A culture of cooperation, rather than rivalry, should characterize relations among the R&D department, business units, and external innovation centers . Companies should foster regular communication and close cooperation among units and put in place incentives that encourage collaboration. Managing the interfaces between various departments and making individual managers accountable for each start-up relationship will be critical to success.

Strong Company Backing

Leading innovators recognize the importance of providing their innovation-focused units with robust backing. They are quick to offer marketing assistance, scaling expertise, management skills, sourcing advantages, and physical infrastructure to the start-ups they are nurturing, viewing the deployment of these resources as vital investments in the development of new business models. Support comes straight from the top—CEOs make it a key topic, modeling the behavior they expect from the rest of the organization and structuring innovation support activities to reflect their importance.

Effective Organization Design

In our research and experience with innovation efforts, we have found that a company’s strategy or innovation unit is often the most logical home for its innovation-support activities. At the same time, though, we find no correlation between any one specific organization setup and successful innovation. Organization design should be customized to suit the company’s particular innovation needs and capabilities and each department’s readiness to take on innovation support tasks.

Effective Leadership

Companies should assemble their innovation-leadership team carefully, choosing executives who combine an entrepreneurial mind-set with a deep understanding of the company’s culture and structure. Their ability to operate comfortably and productively in both the start-up’s and the sponsoring company’s environments enables them to serve as an effective conduit between the company, its investment targets, and the wider world of start-ups and early-stage ventures.

Climb Aboard the Innovation Train—or Wind Up Under It

In our 2012 report on corporate venture investing, Corporate Venture Capital: Avoid the Risk, Miss the Rewards , we addressed the inherent risk of venture investing and innovation support in general, concluding that the greater risk was not to invest at all. Our work since then has only strengthened that conviction. Surveying the landscape of corporate innovation activities, we find that in one industry after another, the leading innovators are stepping up their efforts, as can be seen in the rapid proliferation of incubators and accelerators in 2013. A handful of companies have assembled nearly a full suite of innovation tools and restructured their internal R&D departments to maximize their efficiency. Some leading companies, for example, have set up small, agile, high-performing project teams, reporting directly to the CEO, to work on “tentpole” projects.

As the innovation leaders step up and fine-tune their activities, the distance between them and their slower-moving rivals is widening. The seeds they sowed in 2013 will soon begin to bear fruit, increasing their lead on the competition. The wider their lead, the greater will be the appeal of these leaders to innovation-minded researchers and entrepreneurs, and the better will they be able to recruit key talent from the ranks of innovators with which they are in contact.

If emerging competitors are threatening parts of your business, if technology or regulations are reshaping your company’s value chain, or if your competitors are experimenting with new innovation tools, inaction is not an option. Rather than enter the field simply to keep up with corporate fashion, however, companies should carefully consider the kind of innovation they wish to source and match it with the appropriate innovation strategy and tool. That requires companies to clearly define their innovation goals. Each company will have unique and specific needs and should design its innovation suite with those in mind.

That exercise cannot start soon enough. The train is leaving the station, and companies that don’t climb aboard will miss out on the growth that these innovation tools can unleash.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable contribution of Global Corporate Venturing and its editor, James Mawson, who made available to us GCV’s extensive databases of corporate venture-capital units and deals. You may contact him by e-mail at jmawson@globalcorporateventuring.com .