“More important than the will to win is the will to prepare.”

Charlie Munger, Berkshire Hathaway

For any large global company, acquisitive growth is likely to be a key component of corporate growth strategy. Many business leaders, however, are frustrated by the difficulty of finding, buying, and integrating good businesses. In our work with clients, we often hear the following complaints:

- “There are too few attractive targets. We keep seeing the same old names and spending time reacting to deals that don’t make sense.”

- “We can’t get the numbers to work. The relevant targets are too expensive.”

- “Our outcomes are inconsistent. Even when we win, some deals end up destroying significant value.”

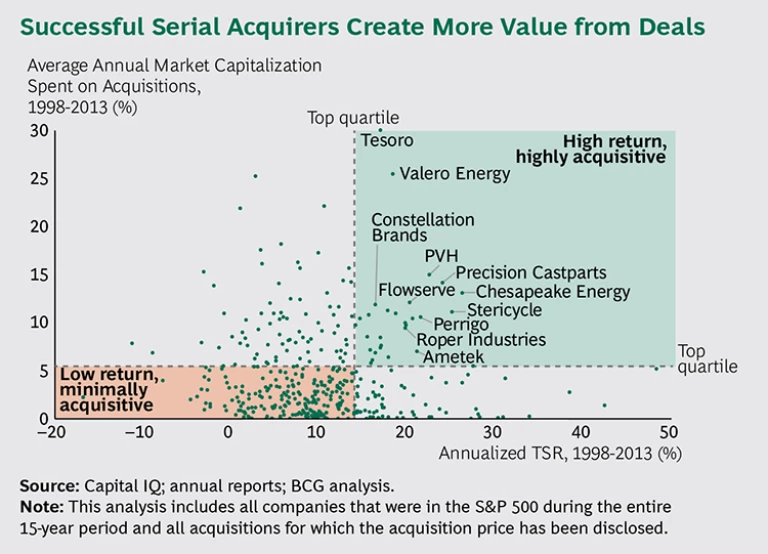

There is a set of companies, however, that routinely overcomes the challenges inherent to M&A-driven growth. Some are public companies, such as Perrigo, the world’s largest manufacturer of over-the-counter pharmaceutical products; clothing and design company PVH, the owner of the Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger brands; or Precision Castparts, a manufacturer of complex components for the aerospace and power generation industries. Others are privately owned, such as the industrial conglomerate Koch Industries.

These companies are successful serial acquirers: they do many acquisitions (on average, spending more than 5 percent of their entity value per year), grow faster than their rivals (as much as three times as fast), and deliver attractive shareholder returns (nearly double the returns of their peers over a sustained 15-year period). (See the exhibit “Successful Serial Acquirers Create More Value from Deals.”) What explains these companies’ ability to deliver successful acquisitive growth when so many other companies stumble?

To find out, BCG recently interviewed senior managers, investors, and sell-side analysts of these successful serial acquirers. As one might expect, each company’s approach contains elements unique to the company or industry; similarly, all share a panoply of standard M&A best practices, such as in-depth due diligence, a strong network of external advisors, and detailed integration plans. But the single factor that most often distinguishes these successful serial acquirers from the rest is their willingness to invest large amounts of leadership time, money, and organizational focus in support of their M&A strategy—in advance of any particular deal. For these serial acquirers, each completed transaction is often the result of years, or even decades, of consistent, patient, and methodical preparation.

More specifically, successful serial acquirers invest disproportionately in three key areas:

- Building and Refining a Compelling Investment Thesis. These acquirers craft a proprietary view of how they create value and use that view to guide their M&A activity.

- Investing in an Enduring M&A Network and Culture. Senior leadership is deeply engaged in the M&A process, and managers at all levels of the organization are expected to source and cultivate relationships with potential targets.

- Defining Distinctive Principles for the M&A Process. The most successful acquirers articulate a core set of carefully designed operating principles. These principles define how the M&A process and people will be managed for discipline without adding bureaucracy.

A Compelling Investment Thesis

An investment thesis is a clear view—grounded in the granular realities of a company’s unique competitive situation, strengths, opportunities, and risks—of how the company will compete and create value over time. (See “ The CEO as Investor ,” BCG Perspective, April 2012.)

For any potential acquisition, an investment thesis helps answer the questions: “why us?” “why now?” and “how do we get there?” Typically, the organization’s investment thesis is articulated explicitly, in a business case that quantifies key sources of expected value creation from each acquisition and that is periodically modified as part of a regular investment-thesis review. Ongoing engagement with the board to ensure alignment on the future M&A pipeline and performance evaluation of past deals is also best practice.

A good investment thesis should be specific enough to clarify where members of the organization should be looking for transactions and to help the company avoid “me too” or off-strategy transactions that are unlikely to add value or are a mismatch with the company’s style of competition. A high degree of precision in the investment thesis empowers the organization to source transactions proactively, rather than just react to pitch books from bankers (which almost always involve a public auction process that drives down returns for acquirers).

Often, the key areas in which a company looks for deals have less to do with industry definitions (as reflected in traditional product or SIC codes) than with certain well-defined company characteristics or transaction types.

Koch Industries, for example, seeks quality businesses with volatile and uncertain earnings, high asset intensity, structural cost advantages, and reasonable valuations. Once a target is acquired, Koch uses its distinctive capabilities and approach to risk to systematically improve performance and grow the business over a multidecade holding period. The clarity of its investment thesis and its disciplined approach to valuation allows Koch to acquire companies in different industries—such as pulp and paper company Georgia-Pacific and electronic-interconnector manufacturer Molex—confident that they will grow faster and create more value as Koch subsidiaries than they would on their own.

Finally, by defining precisely the mechanisms through which the acquiring company will make the acquired business more valuable, an investment thesis gives the buyer confidence in future earnings power. This helps both to define the “walk away” valuation (the price above which a deal will no longer create value) and to identify those situations in which paying an above-average acquisition premium will still result in attractive retained value for the buyer.

An Enduring M&A Network and Culture

Successful serial acquirers also invest continuously in developing internal capabilities, building their M&A network, and cultivating potential sellers—all on a scale that transcends any particular transaction.

This investment starts at the top. The CEOs, presidents, and general managers of businesses at successful serial acquirers are active “hunters” who are expected to spend a significant portion of their time (as much as 40 percent) exploring potential business combinations. These executive leaders often personally oversee the M&A process and regularly mobilize the organization (not only the business development team, but also business unit presidents and line managers) to identify and cultivate potential targets. In the process, they make deal sourcing and the patient cultivation of targets part of the culture of the entire organization.

For example, one serial acquirer we have worked with targets small R&D-intensive start-ups in which decadelong innovation cycles are the norm. As part of its target-cultivation process, the company regularly gives potential targets open access to its innovation centers so that target executives can build close relationships with the serial acquirer’s scientists—relationships that, over time, will help facilitate the deal. Other serial acquirers make a special effort to foster connections with family-owned companies, nurturing their relationships over the long term and positioning themselves for a generational transition that leads to a decision to sell.

Distinctive Principles for the M&A Process

Most executives today know that effective M&A requires a structured end-to-end process from deal sourcing through integration. What distinguishes successful serial acquirers, however, is less the existence of such a process (“the letter of the law”) than the way that process is endowed with rigor and discipline by a set of underlying principles and policies (“the spirit of the law”).

The best acquirers recognize that no two deals are exactly alike. Therefore, rather than develop detailed (and often highly bureaucratic) “cookbooks,” they run their M&A process according to a short list of distinctive principles. These principles are designed to take time and cost out of the M&A process and to ensure that the maximal value is delivered from each acquisition.

The multibusiness conglomerate Danaher is a prime exemplar of this approach; the company has a codified “Danaher Business System” for generating value from acquisitions that it has been refining for more than 30 years.

Such principles serve to focus an organization’s M&A teams on the issues that matter most at each stage of the transaction process. For example, during due diligence, agree on the short list of key commercial deal-breakers early on and focus the lion’s share of effort on resolving them. During bidding, establish a firm “walk away” value that ensures the acquirer does not overpay for the deal. During integration, allocate the majority of team resources to those activities (whether innovation, procurement, or pricing, for example) in which most of the value is expected to accrue.

Proactive Investment in Acquisitive Growth

Any company targeting more growth from acquisitions can learn from the successful serial acquirers who have invested in the three practices discussed above. To do so, however, requires a degree of organizational investment that is significantly larger than most companies make. Given the high stakes and many risks of M&A, however, it is an investment that will pay for itself many times over.

To determine whether you have sufficiently invested in your M&A organization and strategy, ask yourself the following questions:

- “Do we have a clear and distinctive investment thesis that describes the role of M&A in our growth strategy and defines the types of deals for which we are uniquely positioned to add value?”

- “Do our senior executives invest significant amounts of their time refining our investment thesis, hunting for potential deals, and communicating to the organization the importance of M&A in our strategy?”

- “Do we have a career path in place that attracts and rewards executives and functional experts who want to drive acquisitive growth?”

- “Do we have a clear set of principles that define our M&A priorities and the best practices for executing against those priorities?”

For busy senior executives, it is always tempting to wait for the right deal to be presented to them. But for leaders who aspire to consistently and sustainably drive acquisitive growth and are prepared to spend billions to do so, waiting for the right deal to show up isn’t good enough. The time to invest for acquisitive growth is before any particular deal. By the time the pitch book hits your desk, it’s probably too late.