Leadership churn in large companies has

Whether CEOs survive or succumb depends very much on the confidence they generate through the early moves they make. On either side of that precarious year, they are somewhat safer. Before the slump, new CEOs enjoy a period of grace, when the organization, the board, and investors tend to be supportive in the hope of good things to come. And afterward, the CEOs’ longevity becomes increasingly a function of the choices made, the extent of execution rigor, and the ability to sustain reasonable performance expectations.

Studying the Slump

To analyze the sophomore slump, The Boston Consulting Group and Spencer Stuart conducted a joint study into the fortunes of almost 400 new S&P 500 CEOs based in the United States during the past ten years. The aim was to establish the factors behind failing and excelling during the sophomore phase. What made the difference between the CEOs who were “ousted” (whose tenure was ended for performance reasons during their first three years) and the CEOs who were “thriving” (who not only survived for at least four years but also created impressive shareholder value)?

The study investigated three broad aspects of CEO transitions: the context in which the new CEO’s tenure began, the strategic moves made by the new CEO, and the CEO’s performance—or, rather, perceived performance.

- Transition Context: the state of the company at the time of the transition and the profile of the incoming CEO. The state of the company includes its prior performance, competitive position, and reputation, as well as the previous CEO’s record and reason for leaving. The incoming CEO’s profile includes personal qualifications and skills, previous experience, and overlap (if any) with his or her predecessor.

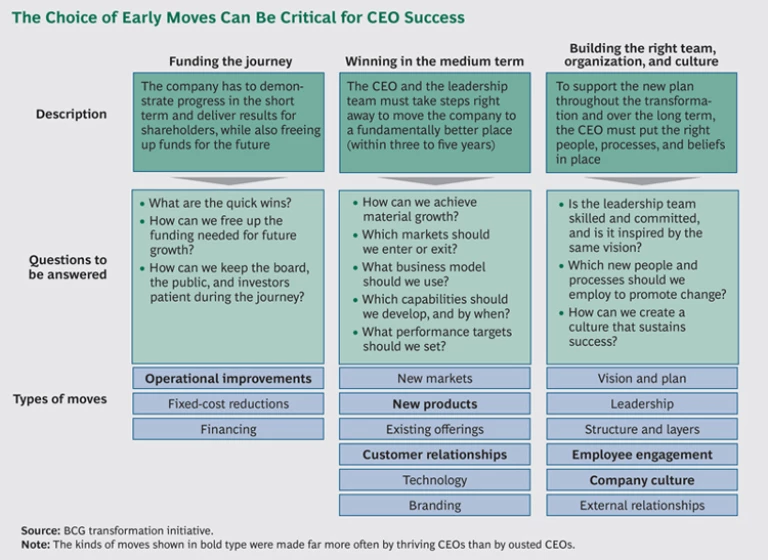

- Strategic Moves: the few game-changing choices made by the CEO, during his or her early tenure, to mobilize and strengthen the company for future growth. A wide range of moves is routinely available to CEOs. (See the exhibit, “The Choice of Early Moves Can Be Critical for CEO Success.”) A few of these, it turned out, were adopted far more often by thriving CEOs than by ousted CEOs, and appear to be conducive to superior performance.

- Perceived Performance: the interpretation of the company’s results during the new CEO’s early tenure. While actual results are obviously important, the perception of those results—by the board, employees, investors, analysts, and other stakeholders—has an even greater influence on the security of the CEO’s tenure.

Defining the Differences

Our main findings for the three aspects of CEO transitions, as they relate to the two groups of CEOs, were as follows:

The transition context will influence the new CEO’s fate but not determine it. For new CEOs, the context is the hand of cards they have been dealt: it is not within their power to choose it, and they have to work within its constraints, but they can play the given cards well or badly. True enough, companies in a challenged state will give rise to a higher proportion of ousted CEOs, and companies in a favorable state—stable or growing companies—will produce more thriving CEOs; but there is no guarantee of failure in the former case, or of success in the latter.

As for the CEOs’ profiles, the two groups differed in several interesting ways. A higher proportion of thriving CEOs than ousted CEOs had graduate degrees (61 percent versus 47 percent), but—surprisingly, perhaps—a lower proportion had previous experience as CEOs elsewhere (12 percent versus 21 percent). Further, a higher proportion had 15 or more years of experience at the company itself (43 percent versus 29 percent). This differential could partly account for the success of thriving CEOs, who might on average have a deeper understanding of the company’s culture, internal functions, and relationship network, and therefore can manage the organization more deftly day to day and plan more shrewdly for the medium term.

In their early moves, thriving CEOs are more energetic and bold. The right moves for any CEO are obviously situational: they will vary according to the company’s financial state, position in the market, and adaptability to changing needs. Nevertheless, our study showed that several types of moves correlate positively with thriving CEO performance.

Overall, thriving CEOs were quicker than ousted CEOs to make bold moves in their first year. They appeared more inclined than ousted CEOs to “go for it”—to launch initiatives that were innovative and ambitious yet still realistic in their timelines. In addition, thriving CEOs tended to strike a better balance between short-term and long-term returns. They also tended to commit more decisively to the financial value drivers that they intended to concentrate on first.

More specifically, our analysis identified a few types of strategic moves that thriving CEOs made far more often than ousted CEOs. (These moves appear in bold type in the exhibit.)

- Making operational improvements for a quick payback to fund future investments. Examples from the study included selling off noncore subsidiaries, reconfiguring the supply chain, and tightening up inventory management—all in the cause of freeing up cash for flexibility in financial investments.

- Developing new products to capture a distinctive market, paving the way for medium-term success. Thriving CEOs made innovative (but realistic) moves: they homed in on products that could quickly secure full value and maximum competitive advantage. Moves of this type included a restaurant franchise’s addition of healthier specialty items to its menu and a retail chain’s creation of high-end sections in its stores—in each case, to appeal to a particular demographic.

- Honing customer relationships in order to refine the service for existing customers and attract profitable new ones. The key is responding to customer needs in a way that promotes mutual value creation. Examples include establishing a “customer first” approach across the organization and tailoring reward programs to specific customer segments in order to strengthen their loyalty.

- Adjusting HR practices to reinforce the new definition of success and increase accountability, thereby boosting employee performance. Examples include redefining performance-management and compensation schemes, and creating self-funding programs to develop and accelerate new capabilities.

- Modifying aspects of corporate culture to support and sustain high performance. Such moves include redefining leadership standards, filling key jobs with more adaptable leaders, changing the operating model to make it easier to take big bets, and redesigning processes for engaging different groups of employees.

For a different look at the approach that successful CEOs take, consider this view from a veteran observer—an operating partner of a private-equity firm. One key factor in early outperformance by CEOs in the sector is the “tone” they set in their first year or two. The decisions they make either pave the way for personal and company success or kindle flames of concern.

At this observer’s firm, the most successful CEOs “sprint to value” by reframing the business opportunity, adroitly balancing their ambition with their capacity for organizational execution. They carefully place “big leaders into big roles” and hold them accountable for executing the selected initiatives—fewer, bigger, and faster initiatives. To minimize surprise hurdles during the sprint, the CEOs ensure that each must-win initiative is appropriately equipped—with sufficient funds, the right team and capabilities, and adequate decision-making rights. The CEOs modulate execution risks, using fast feedback loops with customers, shareholders, suppliers, and the public. With the help of big data and social media, they ascertain which risks are paying off and which are failing, and make course corrections accordingly to realize or reset the expected value. As the company’s track record confirms, the CEOs who sprint to value have consistently produced quick impressive results while setting the organization up for future sustained success.

Thriving CEOs create favorable perceptions of their performance through the presentation, clarity, and credibility of their strategy and execution plan. Thriving CEOs’ early performance was usually superior to that of ousted CEOs, but by no means always. Some new CEOs performed relatively well but were ousted anyway, while others delivered relatively poor results yet survived the sophomore slump, stayed on, and eventually thrived. The differentiating factor here was the way the CEOs were perceived—by the board, investors, analysts, and the wider stakeholder ecosystem.

Even though the thriving CEOs often began their tenure on a more favorable footing (24 percent were immediately named company chair, for instance, compared with only 9 percent of ousted CEOs), we found some evidence that their continuing good reputation was partly due to their more active and skillful way of presenting themselves and inspiring confidence in their abilities—not necessarily through deliberate self-promotion but through a few key behaviors. (See “Consistent Messaging, Ongoing Trust, Positive Image,” below.)

CONSISTENT MESSAGING, ONGOING TRUST, POSITIVE IMAGE

The thriving CEO of an electronics company took over at a very troubled time. After an intensive scrutiny of all the issues, he developed a clear strategy, which he crystallized into a six-word mantra: “Save it, fix it, grow it.” He delivered that message consistently to all stakeholders and always dealt with them straight. He stayed true to the message and explained all actions in terms of the mantra. When reporting results, he never made excuses and never crowed but would keep linking the results back to that punchy six-word mission. Likewise with the decisions he made: closing a plant or spinning off a subsidiary, he would say, was for the sake of saving the company or fixing it. Despite the subdued results in the early phases, he stood firm, and everybody involved kept faith in him as he rode out the storm. The board, the shareholders, and the analysts remained forbearing, and even employees at risk of being laid off generally accepted that he knew what he was doing.

For the record, he did in the end save the company—or, rather, he mobilized the workforce to do so—by “fighting fires” and generating quick cash to keep creditors at bay. He went on to fix the company, by smoothing operations, reconfiguring the leadership structure, and cutting costs and staff. And eventually he managed to grow the company, by expanding the sales force and breaking into emerging markets.

For one thing, they were generally far more adept at articulating a simple, compelling story line. They demonstrated depth and foresight, communicated an inspiring plan, and showed an appetite and aptitude for executing that plan. They were clear about the financial value drivers they had targeted, and focused on them intently. They visibly set the pace. When an initiative failed, they owned up to it and made no attempt to explain away the failure. With their cogent and transparent agendas, they instilled long-lasting confidence in all stakeholders.

In contrast, when ousted CEOs performed well and yet were ousted, the reason seems to be that they failed to come across as convincing. They appeared unfocused, giving the impression of making moves just for the sake of it, or of making more moves than the organization could handle. Even when they made textbook decisions, they did so without conviction, and the decisions appeared haphazard rather than integrated into a coherent plan. And they failed to set appropriate expectations for the various stakeholders. So even when their moves proved successful, their performance was viewed as uninspiring or falling short of expectations, or was credited to market dynamics rather than to the CEOs’ own stewardship.

Tilting the Odds

New CEOs have to play the hand they’ve been dealt. If the company they are taking over is a troubled company, and the board is impatient, and the predecessor CEO has now become board chair, so be it. Those are the realities. Where you can make a difference, and improve your odds of becoming a thriving CEO rather than an ousted CEO, is in the choice and speed of moves that you make and the manner in which you make them. That is the way to imbue stakeholders with confidence—in the company, in the results you produce, and in you as CEO.