Across almost all sectors and regions, companies face unprecedented disruption. The competitive advantages that once gave companies a defensible position—their product lineup, scale, or legacy position—are no longer as secure as they were. Some upstart with a newer and more agile operating model will start taking market share—if it hasn’t already.

In the face of this volatility and complexity, most businesses must transform, meaning a comprehensive change in strategy, operating model, organization, people, and processes. More than ever before, transformation is an imperative. In fact, forward-thinking companies are launching preemptive transformations while they still hold a dominant market position, retooling themselves to stay ahead. The hard reality, however, is that many transformations fail. Some 75 percent fall short of their targets—in terms of value generated, timing, or both.

The Boston Consulting Group, through work with clients in transformation efforts around the world, has developed an approach that flips the odds in a company’s favor. This report is an effort to give transformation leaders the tools and approaches to lead a successful and sustainable transformation effort. (Our transformation approach is illustrated In " Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence ," which describes concrete actions taken in transformations across industries and regions.)

Unprecedented Disruption

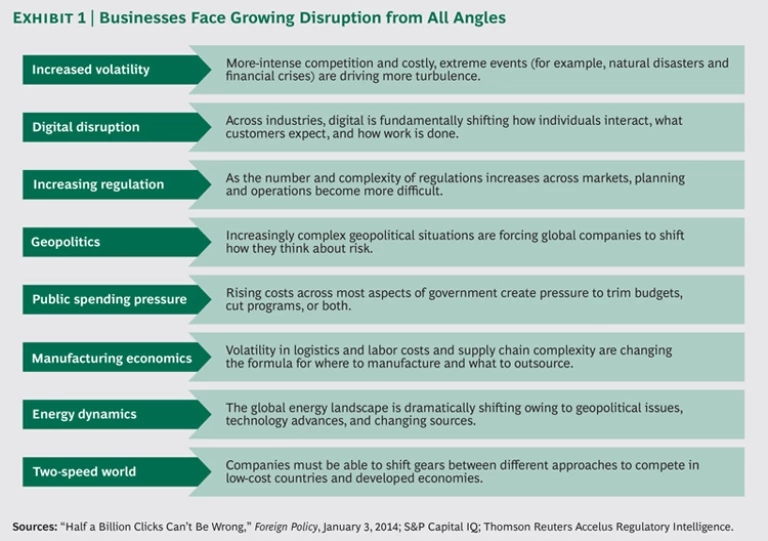

Across industries and regions, the need for business transformation is enormous and growing. The competitive environment today is far more unpredictable than it was even a decade ago, with disruption arising from all angles. (See Exhibit 1.)

Digitization and globalization are blurring the lines between sectors as well as between traditional competitor groups. Technology is changing consumer behavior, empowering start-ups, making pricing more transparent, and reducing product life cycles. Today’s “two-speed world,” characterized by rapid growth in emerging economies and slower growth in developed countries, forces companies to develop unique strategies for each environment. Additionally, companies must rethink—and continually reassess—their operational footprint, owing to changing costs, evolving demand, and unfolding trade restrictions. (Our transformation framework can even be applied to nations, as the Nordic Agenda report demonstrates.)

As a result, the traditional sources of competitive advantage—market position, scale, or legacy—are diminishing, and established operating models are becoming obsolete. That leads to greater volatility within industries, creating a churn effect in which the dominant player is increasingly overtaken by more nimble companies with stronger business models.

According to research conducted by BCG, the probability that a sector’s market-share leader is also its profitability leader declined from 35 percent in 1950 to just 7 percent in the current environment. During the same period, volatility in earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) margin increased nearly fivefold. A leading company that misses one market shift loses three to five years in development time, which is enough to cede the leading position. Miss two turns, and your company is in real danger.

An Imperative in Most Companies and Sectors

In a shifting environment, most businesses must transform, meaning a fundamental change in strategy, operating model, organization, people, and processes. For most companies, the urgency is high; for others, it is an ongoing, adaptive process. In both cases, though, the transformation fundamentally alters the trajectory of the company. Equally important, it is not a onetime event but an ongoing process of evolution as market conditions continue to change.

Successful transformation normally requires rapid, short-term improvements to the bottom line to establish traction and to position the company to win in the medium term. At the same time, organizations need to build the right team, organization, and culture to achieve sustainable results over the long term. All of these aspects need to happen in parallel.

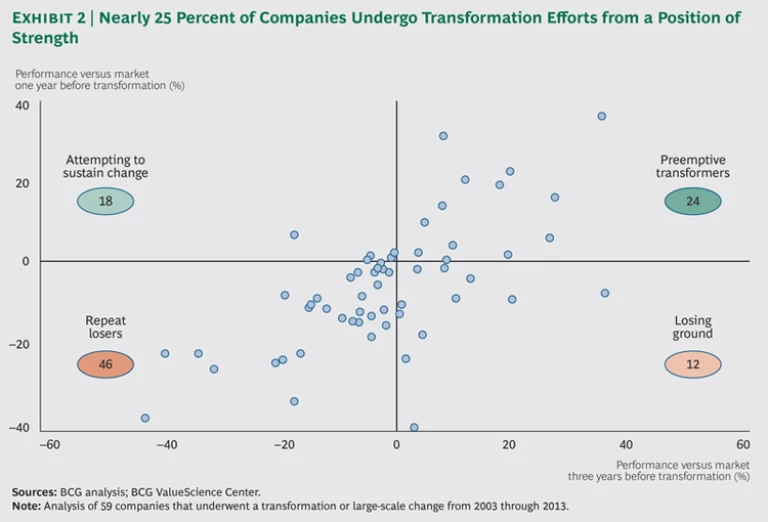

In the past, a transformation effort was perceived as a radical solution indicating that a company had broad and systemic problems—that is, that it had no choice but to change. That perception is increasingly outdated. In fact, fewer than half of BCG clients that have undergone a transformation effort over the past decade had been chronic underperformers. Indeed, nearly 25 percent of them were consistently ahead of their competitors. Leading companies in the sample chose to undergo preemptive transformations that further reinforced their competitive strengths. (See Exhibit 2.)

Yet while almost all companies will need to transform themselves at some point—market leaders and laggards alike—the reality is that many transformation efforts fail. Evidence from the experiences of non-BCG clients undergoing publicly announced transformations from 2003 through 2013 shows that up to 75 percent of those efforts fell short of their targets, in terms of implementation time, value captured, or both. Only 25 percent were able to capture short-term and long-term performance gains compared with their sector average.

An Approach That Flips the Odds of Success

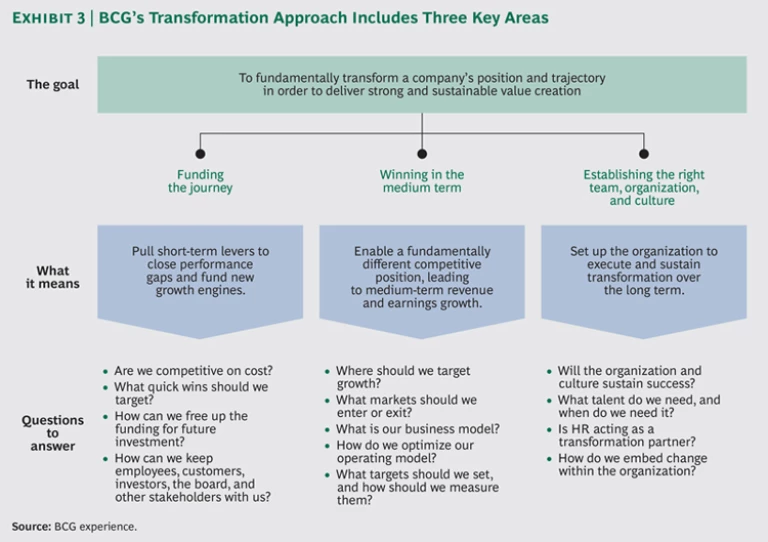

On the basis of our experience helping to implement transformations across industries and regions worldwide, we have developed a proven methodology that can help companies exceed their target impact. As Exhibit 3 shows, the methodology includes three key areas, which we will discuss at greater length in the remainder of the report:

- Funding the journey: pulling short-term levers to establish momentum and fuel new growth engines

- Winning in the medium term: developing the operating and business models to increase competitive advantage

- Establishing the right team, organization, and culture: setting up the organization for high performance

The underlying motivation for a transformation must be to create strong and sustainable value for the institution and its key stakeholders. For public companies and many private companies, total shareholder return (TSR)—which captures change in share price and dividends paid to the company’s shareholders—is the most important lens to assess the success of a transformation. The underlying logic of value creation also often holds for state-owned enterprises.

Most important, the Turnaround: Transforming Value Creation lens helps companies focus their transformation efforts on the levers that can have the greatest impact (organic growth, reduced operating expenses, better asset productivity, and others). This explicit focus helps ensure the best use of available human and financial resources, enabling companies to fund the journey and win in the medium term. This approach is also a powerful means of communicating the transformation agenda to key stakeholders, such as shareholders. (For a case study of TSR-driven transformation, see the discussion of VF in " Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence .")

Funding the Journey

A central challenge of transformations is that they typically take several years to complete, depending on the size of the company and the scope of the changes required. During that time, senior leaders face constant pressure—from the board, employees, shareholders, and other stakeholders—to show momentum and deliver immediate results.

Leaders must win in the short term to win in the medium term. Early, achievable, tangible wins energize the organization and generate the buy-in and confidence of managers and employees. These early measures are also important because they achieve commercial wins, reduce costs, improve the top and bottom lines, and free up cash—all of which can drive the operational improvements required to put the company’s performance among the top quartile operationally of its peer group.

The four types of levers for funding the journey are revenues, organization simplification, capital, and costs. Most often, companies go after the obvious: cost-cutting and organizational optimization. However, revenue and capital levers, while often overlooked, can generate a sizable impact as well. (Read about how a consumer-packaged-goods company funded its transformation journey in " Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence .")

Revenue Levers

Revenue levers can generate as much as a 10 percent increase in top-line growth and a 5 percent EBIT improvement. Go-to-market optimization should focus on pricing effectively, deploying and incentivizing the sales force for the highest impact, and optimizing marketing and advertising spending.

Pricing is the language of business. It drives brand perception, shapes customer behavior, and ultimately propels earnings. Pricing initiatives can typically drive revenue increases of 1 to 2 percent, gross-margin increases of 5 to 10 percent in the short term, and gross-profit increases of 50 percent or more over two years and beyond. Because pricing is so critical, companies need to develop it as a strategic capability, based on customer insights and an analytical approach. Typical quick wins include improving customer targeting, renegotiating accounts, disciplined management of discounts, and optimizing promotions.

For example, an automotive manufacturer undergoing a large-scale transformation was facing a decrease in demand and an increase in competition. Aftermarket pricing was one of many levers the company used. By implementing a systemic pricing model for its service business, the company was able, within one year, to increase its competitiveness at the parts level, leading to an increase of 4 percent in the weighted-average price it could charge and a 10 percent increase in total EBIT.

Sales force effectiveness improves the top and bottom lines. Through improved customer targeting and engagement as well as better deployment and enablement of sales force field staff, a customer-centric sales process that is aligned with business objectives can help a company achieve improvements of 10 to 15 percent in revenues and profit. Activating the sales team is a practical, targeted approach to driving rapid, near-term results and making the sales force the engine of a broader transformation effort.

One mobile operator facing increased competition did not have an optimal channel or distribution structure. By implementing a new incentive structure and channel model and deploying its sales force more effectively, the company was able to capture a 10 percent increase in EBIT within the first year.

Marketing and advertising are critical revenue tools. Many companies spend as much on marketing and advertising as they do on capital expenditures but with far less analytical rigor. BCG’s proprietary research shows that the rules of thumb and shortcuts many marketers use to make decisions don’t yield better results; in fact, they can even destroy value. Typically, up to one-fourth of marketing spending is inefficient. By reallocating those resources, companies can achieve the same level of sales for 10 to 20 percent less—or drive 3 to 8 percent higher volume with the same spending levels—within the first year.

The good news is that there have never been more tools and models available to help marketers improve their marketing performance. Unfortunately, in our experience no tool or model is sufficient on its own. Achieving substantial positive results requires pulling levers across the strategic, tactical, and operational levels to create a common currency of marketing performance and the capability to measure it consistently across brands, products, locations, and campaigns over time.

The experience of a leading global consumer-packaged-goods player, one of the 20 largest media spenders in the world, serves as an example. The company was unable to measure return on marketing investment across its global portfolio. This issue became more pertinent when investors began questioning the efficacy of the company’s recent increases in marketing investment. Building a common measurement platform allowed the company to strategically re-allocate spending across its top 50 brand and market combinations and tactically optimize spending across activities at the local level. The result was an increase of up to 5 percent in sales achieved with the same marketing resources over 18 months.

Organization Simplification Levers

Streamlining the organization can both dramatically increase the punch and implementation power of the organization and significantly reduce layers and costs. Recent research has found that up to half of performance requirements are contradictory and that overall organizational complexity has risen 35-fold since 1955. It is no surprise that employees at the most complicated organizations tend to be the most disengaged and unproductive. The layers of complexity lead them to focus on the wrong things and ultimately miss their objectives .

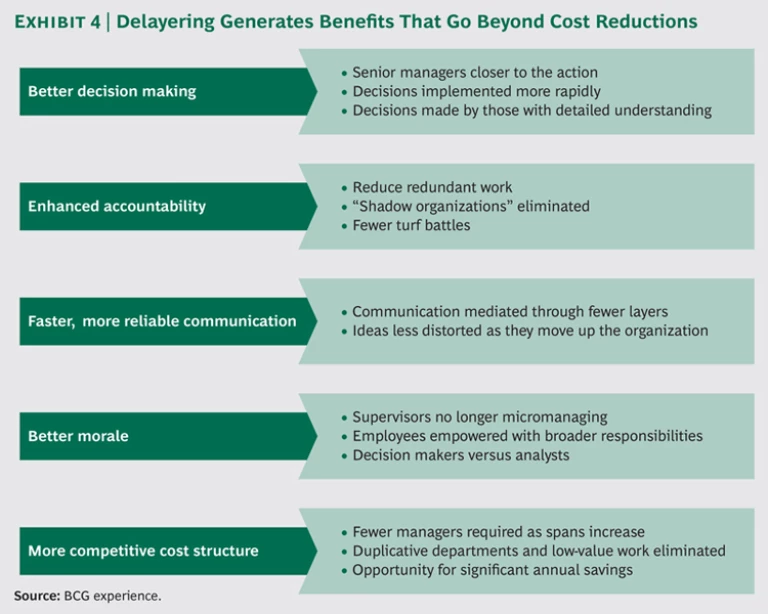

Delayering is a proven approach to reducing complexity that cuts through organizational clutter and increases the focus and performance of the team. It often yields sizable cost savings—typically 15 to 30 percent in indirect labor costs—as well. Yet delayering is more than just a cost reduction exercise. By removing bureaucratic hurdles, the process enables better and faster decisions and a more effective use of talent. Cultural changes and values spread more easily throughout the organization, and managers perform better. Individual employees benefit as well, through greater clarity of the organization’s purpose, a clearer link between performance and recognition, and less micromanaging. (See Exhibit 4.)

A leading global transportation provider facing a dramatic squeeze in margins delayered and streamlined the workforce at its headquarters facility. Within four months, it reduced its head count by 40 percent, shed ongoing projects from more than 100 to approximately a dozen, and significantly increased the focus and speed of its decision-making and execution power. In turn, this simpler operating agenda catalyzed execution, vaulting the company’s performance from the median to the top quartile in its peer group within three quarters.

Capital Efficiency Levers

Utilizing capital efficiently is vital during a transformation and can help with short-term cash needs and improve return on investment, positioning the company for growth. A strategic approach to capital allocation can help companies prioritize investment projects, improve financial discipline, and develop a strong governance structure to guide capital expenditure and growth projects.

Net working capital often holds potential for unlocking short-term improvements. Aspects include inventory, accounts payable, and accounts receivable.

Optimizing net working capital—and managing the interfaces and trade-offs between fixed assets and cost efficiency—can reduce working capital by 20 to 40 percent, often within the first year of implementation.

For example, a global industrial-engineering company had piled up inventory for years as a result of market volatility and needed to reverse the trend, especially because financing costs had risen drastically. It tailored quick-win actions for each plant, while a small team worked to strategically reduce inventory and optimize raw-material stocks across plants. After only one year, the company had realized a $450 million cash release through a 35 percent reduction in total inventory.

A retail company that had an aggressive, six-month timeline to unlock cash provides another example. Over three months, a small team focused on extending payment terms for the top 1,000 suppliers, representing a total of $700 million in payables. After a detailed benchmarking analysis, the company set up and communicated specific targets for each supplier. As a result, the company realized a $180 million cash release in the first quarter alone and a $270 million increase in available cash after six months.

A deeper analysis of fixed assets can also yield dramatic improvements. In addition to asset reduction options—such as an outright sale or defunding of future capital outlays— best-in-class companies manage both the need for assets and the way assets are utilized. Asset needs can be lowered through reduced product and customer complexity. A complex portfolio of products often requires broad production assets, along with ramp-ups, ramp-downs, and changeovers. Streamlining the portfolio of products or customer accounts and rethinking outsourcing decisions can quickly improve productivity and allow for a reduction of assets.

Take the example of a large industrial-engineering company that was struggling to reach its ambitious targets for return on capital employed (ROCE) and needed to reduce the $6 billion of capital employed in operations. A team thoroughly analyzed the amount of capital tied up in each of the value chain steps across all three of the company’s business divisions. The company also conducted a strategic review of each plant and activity from a ROCE point of view. As a result, it defined a plan to divest selected parts of operations by either optimizing remaining assets or outsourcing activities to third-party operators. After one year, the company had reduced capital employed by $650 million—including $200 million in the first three months—with a minimal impact on EBIT.

Cost Reduction Levers

Certain measures can lead to reductions of 10 to 25 percent in the cost base, making them an essential component of a transformation. Short-term levers such as improving procurement, shuttering facilities, and reducing personnel and nonpersonnel costs can be very effective—and sometimes mission critical. Companies can also often capture quick wins from more profound cost-reduction activities, including supply chain, lean manufacturing, and process improvements.

Better management of the cost of goods sold (COGS) and procurement can create tremendous value. Measures such as these can lead to a 2 to 5 percent margin improvement and have a tremendous impact on value creation. A leading European retailer, for example, had basic procurement practices and limited coordination across business units. The company created a procurement center of excellence and began running coordinated, analytically backed negotiations with all of its main suppliers, an approach that unlocked annualized savings of 3 percent of the addressed COGS in the first year.

Personnel cost reductions are often necessary. As market conditions change, companies must adapt their workforce accordingly; personnel reductions can drive a 20 to 40 percent reduction in labor costs, in many cases within the first 12 to 18 months.

In one example, a leading European contractor was facing major margin pressure owing to market contraction and the underperformance of several projects. A benchmarking analysis showed sales, general, and administrative (SG&A) costs that were 30 to 50 percent higher than those of the contractor’s peers—something that previously had not been fully clear given varying and nontransparent accounting practices. A further review revealed overlapping roles and management layers across the organization. The company launched an effort to reduce personnel, delayer, and simplify the organization. Through these measures, the company closed the SG&A gap with its peer group in less than six months and restored EBIT competitiveness.

A global cable group facing margin pressure after several years of low demand growth and competition from low-cost countries took another approach to cutting costs. The group, which had been built on serial acquisitions, launched a quick-win lean program across its plants, focusing on overall equipment effectiveness. It is now on track to reduce personnel and waste by 30 percent in 18 months.

Nonpersonnel cost (NPC) reductions also improve overhead. Roughly 50 percent of overhead costs do not come from labor. By addressing these, companies can realize NPC reductions of 10 to 30 percent. Primary cost levers include buildings and equipment, utilities, travel management, fleet management, IT, and business services.

A European bank faced a sharp increase in operating expenses because of price hikes and inefficient and ineffective use of shared services by its subsidiaries. By creating cost transparency, the bank identified its high-impact cost categories, thereby clearing the way to achieve a 20 percent NPC reduction within the first year.

Winning in the Medium Term

Funding the journey is an essential first step but not the only step; although the levers applied to fund the journey can be very powerful, they often don’t have the scope to fundamentally change the business and create sustainable competitive advantage. The second step, winning in the medium term, requires a more profound change: a fundamental rethinking of the target operating model, an end-to-end lean approach to streamlining the business, and a revamped business model. It’s an ambitious undertaking, but it’s necessary if the company is to get back to generating sustainable growth and create a vibrant and exciting future.

Developing the Target Operating Model

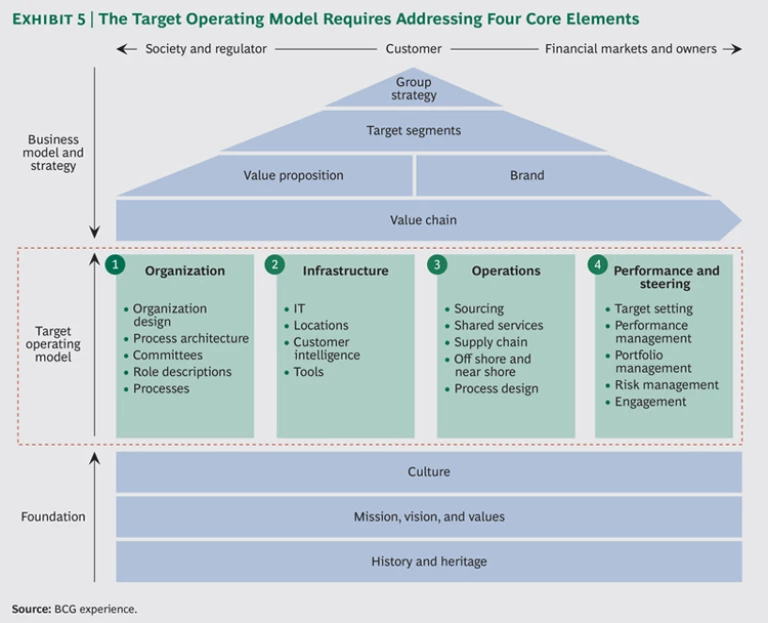

To develop a target operating model that is aligned with the goals of the transformation, a company must first make an honest analysis of its current operations. The process starts with assessments and benchmarking but also relies on a deep understanding of the complex interactions across the business and value streams, acquired through an evaluation of the organization, infrastructure, operations, and performance and steering. (See Exhibit 5.)

By evaluating these four areas, companies will almost certainly uncover several core processes that it needs to eliminate, replace, or improve. That can often happen through a lean approach, discussed below. However, in some cases that’s not enough and, instead, companies must fundamentally reimagine these core processes and rewire their approach to delivering products and services to their customers.

The most obvious lens is digital. New technologies and evolving customer behavior are forcing companies to radically improve their products and services. And companies are also finding enormous value by applying digital technology to internal processes, increasing transparency, and giving all levels of the organization tools to make quicker and more effective decisions.

Bringing the Target Operating Model to Life: End-to-End Lean

In designing the target operating model, a lean approach unlocks the greatest value. This approach has traditionally been used in manufacturing facilities and supply chains, but it increasingly applies to service industries and white-collar environments as well. An end-to-end lean approach starts with the value proposition, looks at it from the customer’s perspective (rather than internally), and breaks down processes into a series of discrete steps.

Through an initial lean diagnostic, companies often find a mismatch between their processes and the goal of serving the customer; this insight can also serve as a basis for how to bring the target operating model to life. In redesigning each process, step by step, the goal is to create value for the customer and eliminate waste. By using the customer experience as the starting point, companies can eliminate friction between departments and business units and across value streams.

Because these changes are often major initiatives, pilot tests can help prove the concept on a smaller scale and thus win supporters. As the company shifts to the full rollout (often in conjunction with other transformation efforts), opportunities and improvements begin to compound.

In addition to driving process excellence, lean cultivates a learning organization that focuses on continuously improving and creating value for the customer. This type of learning organization is essential to sustaining a multiyear transformation effort. (For a case study, see the discussion of a leading bank's lean approach to transformation in " Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence .")

Rethinking the Business Model

In a transformation, companies must put everything on the table. That includes rethinking the core business model. Companies must address a core question: “What do we do?” To answer this question, companies must zero in on their value proposition and how they deliver on it. This means a deep dive into several aspects of the business:

- What target segments are we serving? What should they be?

- What products and services do we offer? Are we focused on the right ones?

- What is our revenue model? Is it aligned with our long-term strategy and growth goals?

Answering these questions often prompts a fundamental shift in strategy, a reevaluation of the value proposition, and a focus on new products and services. Companies can emerge from this process to pursue new business models, such as an innovative go-to-market approach or a new digital strategy.

Even as the company moves toward a new business model, it cannot simply ignore its legacy business model. Leaders will have to think critically about how to juxtapose legacy business models that are still making money with newer and entrepreneurial bets that are aligned with the future strategy of the company. The longer-term objective is an ability to adapt and make progress with a flexible plan that can be refined over time. (For more, see “Common Transformation Traps.”)

Common Transformation Traps

A bank located in an emerging-market nation realized that to become a leader in its region would require a game-changing strategy. It started completely from scratch and developed a new value proposition that emphasized transparent pricing, same-day turnaround on most services at consistent quality, and entrepreneurial and engaging staff. At the same time, the bank launched a new, far simpler business model—with fewer than ten distinct products—that was geared to growth. The bank is now rolling out the new strategy, with the goal of operating several hundred branches in three years. Beyond the obvious benefits, the measures have brought new energy to the organization and inspired it to take on the giants in its market.

The shift does not need to be as dramatic for all companies. McDonald’s has been a leading food-service company for decades; its success is due in part to its obsession with constantly improving its business model. Because McDonald’s operates in more than 100 countries, it needs to keep a close eye on its customers and ensure that it can deliver on its value proposition by offering the right products, at the right price, to the right customers. It has embraced the cafeteria concept for its stores in Europe, for instance, and created a specialty-coffee-shop experience with espresso and cappuccino in the U.S. Both are ways to deliver on the same fundamental business model and value proposition. (For a more detailed case study of a customer-focused transformation, read about the experience of a German health insurer in " Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence .")

Establishing the Right Team, Organization, and Culture

The third key element of a transformation is the people component. Without a strong focus on a company’s team, organization, and culture—through a strong change- management effort—the transformation will fail. Such an effort requires five essential success factors:

- Ensure commitment that allows the leadership team to lead from the front.

- Simplify the organization and develop the culture to support high performance.

- Develop talent to fill the critical roles required to transform.

- Install an HR team that can act as a transformation partner.

- Deploy change management tools to drive results.

Leading from the Front

Nothing contributes more to the success of a transformation than its leaders.

Transformations are complicated initiatives that take place over time, with significant potential for miscommunication and misplaced priorities by the time they filter down the line. As a result, transformations must be led from the front, by committed leaders who consistently embody important behaviors and hold themselves accountable for results.

In many industries undergoing significant market, competitive, and technological shifts, transformation is the new normal. Companies need to make sure that they have the right leaders with the right skills “on the bus” and that these leaders can work in effective teams, set the right priorities, and provide the leadership needed to make change happen.

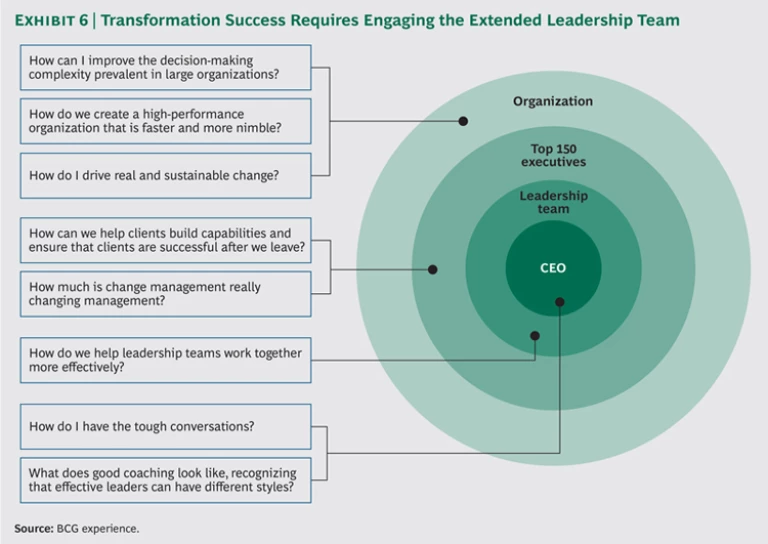

Senior leaders must be able to engage not just the senior team but also the extended leadership team—the next 100 to 200 managers in the organization chart—to ensure that all leaders have the right level of commitment to the transformation. (See Exhibit 6.) Typically, this requires convincing some skeptics who may question the need for change or the urgency or validity of the transformation or who may resist it because it changes their span of control, responsibilities, or other factors.

Winning over those skeptics is a central challenge for leaders. It requires helping leaders work through several phases—denial, resistance, exploration, and commitment—with specific interventions that vary depending on where leaders are stuck:

- Denial. In this phase, leaders may simply ignore requests, assuming that the initiative won’t last. Overcoming denial requires making a clear case for change and reinforcing the fact that the transformation is for real.

- Resistance. This is the most common sticking point, at which some leaders seek, either actively or passively, to undermine the initiative. The key to engaging leaders in this phase is to air the points of resistance and address them openly. Some concerns are legitimate, and heading them off increases the odds of success.

- Exploration. For leaders at this point in the journey, the goal is direct engagement and reassurance, through quick wins, that the process is working.

- Commitment. Leaders are fully on board for the transformation and willing to help engage the rest of the organization regarding next steps.

Each leader should be assessed for past performance, current readiness, and future potential across four dimensions: knowledge, soft skills, experience, and motivation and personality traits. Leaders also must have a foundation in adaptability and change leadership. A shortcoming in any one of these can be a warning sign.

However, the right leaders will fill roles in varying ways throughout the journey, from champion of the venture (offering sponsorship and support), to resource (offering information and direction to employees, managers, and other leaders), to example (embodying the right actions and behaviors), to compassionate team member (acknowledging that change can be disruptive and stressful). (For a case study of how leadership can impact a transformation, see the discussion of Nokia in " Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence .")

A transformation often brings significant turnover and, consequently, many leaders who are new to the organization. Beyond understanding their commitment to the change journey, it is vital to ensure that they have the right tools and capabilities to lead and manage change—a fundamentally different set of skills from managing day-to-day operations. (For examples of what can go wrong in a transformation, see “Four Reasons Why Executive Teams Underdeliver.”)

Four Reasons Why Executive Teams Undeliver

Strong leadership can be a critical factor in executing a transformation, yet there are also many ways that ineffective leaders can undermine the effort. The following are among the most common:

- Lack of Clarity or Purpose. Individual accountabilities among the executive team are not aligned with business requirements; the team is not clear on governance bodies and roles.

- Individual Personalities. Senior executives have been promoted for individual achievement rather than team efforts; talent and leadership styles vary widely.

- Internal Competition. Multiple leaders are vying for the top job, which can erode the open and trusting climate needed for constructive group dynamics.

- Team Structure. Some structures foster a focus on personal accountability and individual business units instead of the overall organization.

A High-Performance Organization and Culture

To execute the new strategy and target operating model and sustain higher levels of performance during the transformation and beyond, a significant number of people will need to change what they do and how they behave. Improvements in customer focus, collaboration, innovation, simplicity, and productivity—typical goals of a transformation—all require changes to behavior. Behavior, in turn, is shaped by the organization context in which people work. To improve and align the ways that people behave, companies will need to revamp their organizations.

On the basis of BCG’s client work, we have observed that high-performance organizations and cultures have three characteristics:

- Individuals and teams that are engaged in achieving the desired results

- Individual and collective behavior that is clearly linked to the company’s unique strategy

- A work context that reinforces the desired behaviors and culture

If any of the three elements is not in place, leaders need to actively change the organization and culture—by setting the target culture and then changing the organization context to reinforce that culture. Aspects include the right leadership behaviors, organization structure, role mandates, people policies, performance metrics and management, rewards and recognition, and the physical work environment. (See the sidebar “Key Lessons in Cultural Change During a Transformation.”) This process is a microcosm of the overall transformation effort, and it follows the same path:

- Diagnose the current situation. How do people behave? What culture do we have, and why?

- Set the target culture. What behaviors and culture do we need?

- Identify critical interventions. What aspects of organization context do we need to change?

- Develop a path to get there. How do we make change happen?

Key Lessons in Cultural Change During a Transformation

Creating a high-performance culture is typically only one of several objectives in a transformation. Many other objectives, especially those in funding the journey, have a clear return on investment. The benefits of culture change can be harder to pin down and quantify—but in many ways, culture change is the most critical element for sustainable success. So leaders need to ensure that they are fully committed to protecting resources and actions to change culture.

Transformation requires pulling levers from the first day of the process, and that makes it challenging for leaders to stay ahead. Compounding the problem, many work streams associated with the broader transformation are not under the direct control of those responsible for the culture (such as HR).

Accordingly, it’s urgent that leaders move fast in the early stages, to generate a high-level view of the target culture and set a “north star” to guide the overall transformation. This means a clear description of the target culture—and target behaviors—that can be understood throughout the organization.

In addition, companies need to structure the program so that leaders buy into the cultural aspect and ensure that there are appropriate resources to orchestrate the cultural change. Treating culture as an afterthought will erode the transformation—and the company’s performance overall—in a thousand small and large ways.

Effectively changing the organization context is an iterative process. The actual High-Performance Culture will evolve over time in response to refinements in the business model and the strategy.

One essential element of context is organization design. Reporting lines as well as roles and responsibilities, and how those are defined, all significantly shape how people behave. A critical component of the organization design process is the delayering discussed in the chapter “Funding the Journey.” Both processes—organization design and delayering—are necessary to increase the effectiveness and punch of the organization and facilitate the environment that will encourage employees to exercise the desired behaviors.

Organizations need a deep understanding of the interactions between functions and business units, as well as the roles and accountabilities of individual contributors. To understand these dynamics, companies should create “role charters” that define what each employee is accountable for along with “collaboration charters” that define how responsibilities will be shared throughout the organization. (See “A Contrast in Organization Design Approaches.”)

A Contrast in Organization Design Approaches

A telecom company failed to properly define roles and accountabilities and to align individual capabilities with the appropriate roles. The result was that several business units lacked a clear mandate, leading to high turnover among executives in those units.

By contrast, a large global bank achieved greater success in its transformation because it developed a clear organization design, establishing end-to-end accountability for costs and rolling out the new design as part of a comprehensive change-management program. The company globalized business units and functions but gave country-specific chief operating officers sufficient authority to adapt global operating-model design and implement it locally, enabling the organization to quickly roll out the new design with high levels of buy-in across the company.

A Holistic Strategy for Talent

Although leadership is critical, especially during the first six to nine months of the transformation, success over the longer term requires a strategy for identifying and developing talent at all levels and in all critical roles. All transformations require the development of new skills for leadership and functional expertise in disciplines such as pricing, sourcing, lean, and HR.

Our experience shows that no amount of expertise or leadership brought in from the outside is going to overcome an organization’s inability to build capabilities internally. To achieve and sustain the hard-fought gains in a transformation, companies must be able to define their strategic objectives and the capabilities and roles required to achieve them. At the same time, they must be able to plan their workforce needs two to five years ahead, identify and attract talent, train and develop employees, assess and promote the most promising individuals, and engage the entire workforce.

An industrial-goods company was able to deliver on aggressive transformation goals through a fundamental shift in its talent strategy. Without a focus on talent, the company would have failed as it shifted from a local to a global strategy: it started with 80 percent of its staff in its local country but in five years had 50 percent of staff located in the emerging-market nations Brazil, Russia, India, and China. The talent initiative also supported an effort to increase the revenue contribution of the company’s service business to half of total revenues. Four pillars of this talent strategy helped the company deliver on its goals:

- Anticipating and constantly measuring the talent gaps with transformation and business leaders and investing accordingly

- Opening talent pools to very diverse profiles to support a global strategy and updating assessments to handle this diverse new pool of employees

- Marketing the company to potential employees who fit the new strategy, through a targeted employer value proposition and investment of time to standardize the talent experience globally through frequent monitoring of employees’ engagement

- Helping the managers of the company succeed in their human-capital performance objectives with cross-silo talent reviews and career-management and enterprise-development programs at different career levels, encompassing job rotations and a cycle of training programs

The time that the senior leaders of the industrial-goods company invested in talent management was considerable—up to a month annually for each executive. But talent management has become a competitive advantage for the company, which is now a truly global leader in its sector.

HR as a Transformation Partner

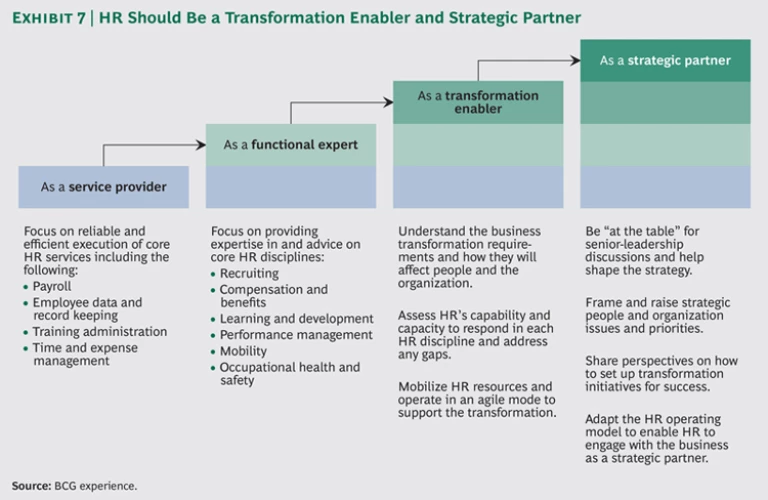

HR is a powerful transformation enabler because transformations typically touch almost all aspects of HR, including organization design, leadership and talent development, workforce planning, recruiting, compensation, and performance management. For that reason, companies need to understand how and where the transformation will affect each HR discipline and the current capability and capacity of the HR function early in the change program. That gives management a grasp of the demands that will be placed on HR and the department’s capabilities and capacity to respond—and an opportunity to address any critical gaps.

In addition, companies need to determine the potential impact of the transformation on the HR organization itself. In the short term, HR at many companies will need to evolve from a mere service provider (focused on administrative processes) and functional expert to a transformation enabler and strategic partner for the business. (See Exhibit 7.) To enable the HR function as a strategic partner, the transformation’s leaders must include HR in planning and provide visibility into the pending changes so that HR has time to prepare for its elevated role in the transformation.

For example, a global technology company with a history of high growth had long required HR to focus on scaling the organization. As growth slowed, the company set out on a transformation journey, and it needed HR to play a critical role as a transformation partner for the business. To begin, the company created an inventory of all the transformation initiatives and determined the impact on various HR disciplines. In parallel, the company conducted a series of workshops with critical HR staff to assess current capabilities, strengths, and weaknesses. The outcome of these sessions was alignment on a focused set of HR priorities that were essential to support the business. The department also put together a roadmap to build new capabilities, enabling it to assume an expanded role. In essence, HR had to undergo a small-scale transformation so that it could help drive the larger transformation of the rest of the company.

Embedding Change Management

Depending on complexity, some 50 to 75 percent of change efforts fail. However, a holistic approach to managing change—one that enrolls and activates leaders at all levels, engages the broader organization, and ensures a high level of confidence in initiative delivery—can powerfully flip the odds in favor of success.

To fund the journey and win in the medium term, many high-impact initiatives need to be identified. It is important to establish an initiative roadmap for each, made up of multiple milestones—typically, 15 to 25 are most effective—along with time frames, financial and operational metrics, and clear accountabilities. This roadmap communicates the story of each change initiative in such a way that the transformation team, on the basis of monthly updates, can easily understand what is happening and can make course corrections to ensure ultimate on-time value delivery.

Beyond the quantitative metrics of an initiative, rigor-testing each initiative roadmap can produce tremendous value. This is a qualitative assessment of the robustness and consistency of each plan that ultimately addresses three important areas:

- Is the initiative roadmap clearly defined, logically structured, and readily implementable?

- Is the financial impact at each step clearly identified, along with the source, timing, and leading indicators?

- Are interdependencies and other known risks identified and understood?

Analysis has shown that roadmaps whose rigor test earned “excellent” scores captured an average of 130 percent of their planned value. One company, which had more than 100 initiative roadmaps with 1,800 specific business milestones, performed rigor testing with every initiative team, leveraging the support of its program management office (PMO). By challenging each roadmap with key questions on these three topics, the company had confidence in its ability to deliver on its aggressive goals.

An activist PMO, one that closely supports senior leaders and the transformation agenda, has time and time again proved critical in enabling and facilitating impact across the business—particularly for cross-business initiatives. The value of getting the PMO right cannot be understated. Only one-third of PMO leaders feel that their PMO has realized its full potential to enable change within the organization. When leveraged correctly, the PMO helps the leadership team maintain an appropriate pace of change and acts as the steward of the aspiration for change, ensuring that there is a clear line of sight to senior executives regarding implementation progress and any emerging issues. At the same time, it must never usurp the authority of the business units or functions in delivering results. The PMO does not need to be liked, but it should have broad-based respect. “PMO used to be a dirty word around here. This PMO has changed that,” remarked a senior leader at a global oil and gas company whose PMO is now recognized as a key part of a major Changing Change Management: A Blueprint That Takes Hold .

Acknowledgments

We would like to first thank the executives and client teams we have worked with executing major transformations over the years for their courage and leadership. At the time of writing, BCG supports 125 ongoing transformation efforts worldwide and has supported more than 500 in all.

We would like to especially thank Paul Millerd and Omeed Rezaian for their contributions in developing content, serving as thought partners, and managing the production process. June Limberis also contributed invaluable marketing assistance on this project.

In addition, we thank the key contributors who helped shape the thinking and contribute meaningful content: Margaret Ayers, Thorsten Brackert, Jean-Michel Caye, Sandeep Chugani, Camille Egloff, Hady Farag, Grant Freeland, Marin Gjaja, Gustav Gotteberg, Kaelin Goulet, Richard Hutchinson, Udo Jung, Jeff Kotzen, Ib Löfgrén, Steve Maaseide, Andreas Malby, Valery Panier, Carrie Perzanowski, Tuukka Seppä, Niclas Storz, Jennifer Tankersley, Roselinde Torres, and Gideon Walter.

Companies that don’t succeed at the second phase of transformation—winning in the medium term—typically fall into a predictable set of traps, which seem obvious but are surprisingly difficult to avoid: