Although e-commerce is the fastest-growing retail channel by far, its growth is being constrained by barriers to cross-border transactions. Those barriers will eventually be dismantled, and online retailers, carriers, and other service providers will need to take action to compete in an effectively borderless world.

E-Commerce Is Growing Fast...

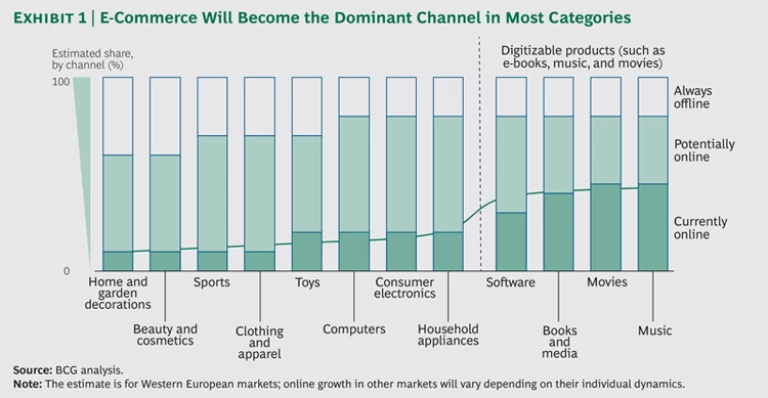

The Boston Consulting Group cataloged the barriers to e-commerce in “ Breaking Through the Barriers to Online Growth ” (BCG article, June 2013). The article’s conclusion bears restating here: when the e-commerce channel is fully developed, retailing will be a multichannel activity, with online the leading channel for domestic and cross-border sales in most product categories. (See Exhibit 1.)

Nowhere is the rapid expansion of e-commerce more apparent than in Asia. As we discussed in The World’s Next E-Commerce Superpower: Navigating China’s Unique Online-Shopping Ecosystem (BCG report, November 2011), China is leading the way, shedding its identity as solely a production center and emerging as a burgeoning consumer market, with an increasingly affluent and populous middle class eager to embrace online technologies and adopt the developed world’s consumption styles. Asia’s e-commerce growth rates are in the double digits in most product categories, and it’s no coincidence that China is the only major market where the largest retailer, Alibaba, is a pure-play Internet service.

…But the Cross-Border Variety Is Still Struggling

The main growth, so far, is mostly domestic, as barriers to cross-border transactions are constraining the growth of cross-border e-commerce in Asia as well as in Western markets. These barriers include the following:

- Unreliable and Lengthy Transit Times. Consumers want shorter, more precise, and more reliable delivery windows for both domestic and cross-border purchases.

- Complex and Ambiguous Return Processes. Fully tracked, easy-to-arrange returns should be a standard option on all e-commerce sites.

- Customs Bottlenecks. At present, dissonant customs practices create significant scheduling uncertainty for shippers. Customs regimes need to be harmonized and their timing made more predictable.

- Limited Transparency on Delivery. Some parcels aren’t tracked at all, and the tracking information that does exist lags the actual delivery by about six hours. Tracking is linked to specific delivery windows, decreasing the value of the information for short transit times.

- Price Opacity. International shipping options are often complicated by VAT and customs charges, and shoppers can’t determine the final landed cost of an item, even after they click “buy.” This uncertainty discourages purchasing.

- Limited Ability to Alter Delivery Times and Locations. At present, if consumers’ plans change, they cannot change delivery times or locations for internationally shipped goods if the parcel is already in transit, as they can with most domestic deliveries.

Bracing for a Borderless World

With so much at stake and with so many competitors jostling for a piece of the e-commerce action, it’s only a matter of time before a number of players in the cross-border e-commerce ecosystem find ways to surmount these barriers at an acceptable cost, with encouragement from public-sector bodies such as the EU. An integrator might be able to manage down the costs of its end-to-end service, or postal operators might collaborate to act as quasi integrators to take advantage of their low-cost residential delivery. Commercial airlines may have a role to play connecting domestic residential networks to international senders. Intermediaries are already stepping in to link electronic retailers and domestic carriers for cross-border service, while integrated online retailers and order retrieval companies are preparing to offer cross-border delivery services to third parties.

Cross-border e-commerce currently accounts for 10 to 15 percent of total e-commerce volume, depending on region. That share is sure to expand as the barriers are dismantled. By 2025, annual global cross-border e-commerce revenues could swell to between $250 billion and $350 billion—up from about $80 billion today. Asia will account for some 40 percent of those cross-border revenues, making it far and away the center of the e-commerce world. Europe will account for about 25 percent of revenues, followed by North America at 20 percent.

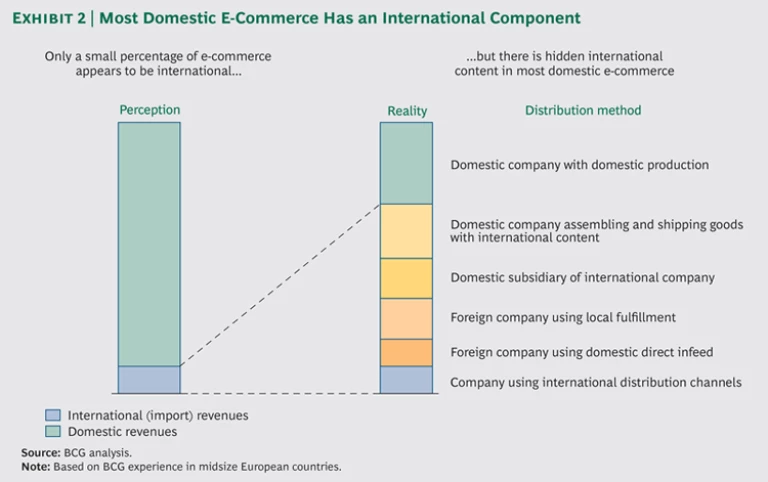

The current figure might look small compared with domestic e-commerce flows, but it turns out that domestic e-commerce isn’t so domestic after all. Already, roughly 70 percent of the revenues of domestically anchored carriers in midsize European countries have some kind of cross-border component. In some cases, that component is a direct infeed from a foreign player; in others, a foreign player uses local fulfillment to complete a delivery; in still others, a domestic company assembles and ships goods with international content. (See Exhibit 2.)

Implications for Retailers

When the barriers to cross-border e-commerce fall away, it will no longer matter to consumers if they buy domestic or cross-border. At that point, retailers will have a golden opportunity to organize their sales not by region but by customer needs, selling products and services matched to particular markets regardless of location.

The giants of e-commerce, Amazon and Alibaba, are already developing this business. Amazon’s Multi-Country Inventory selling program streamlines cross-border transactions, primarily in Europe. Alibaba is cutting deals with domestic carriers in several countries to eliminate bottlenecks and control cross-border flows. One such deal, with Lithuania Post, opens a gateway into Western Europe and Russia. Other retailers should consider following suit.

The emergence of an effectively borderless world will also eliminate many supply-chain inefficiencies, such as circuitous delivery routes. At present, if Australian consumers purchase goods through a UK-based online retailer, the parcels are first shipped from China to the UK before they’re forwarded to Australia—a rather sizable detour.

The evolution of cross-border e-commerce is not without risk for retailers. When the cross-border channel is sufficiently robust, manufacturers of both branded and unbranded goods will have the option of bypassing retailers and distributing directly to consumers, wherever they are. Apple, for one, is already selling direct, enabling shoppers in many countries to buy its products online and have them shipped from the company’s contract manufacturer, Foxconn.

Implications for Carriers

Carriers have a critical role to play in bringing this new world into being, acting both independently and collectively to surmount cross-border barriers, standardize service offerings, and improve service quality. Individually, they face the task of determining what kind of cross-border players they want to be, depending on their competitive positions and ambitions. Most will likely opt to position themselves somewhere within the cross-border ecosystem and thus avoid the risk of becoming no more than a domestic subcontractor. Once they determine their place within the greater network, carriers can make the needed investments in IT, sales and marketing, and other functions essential to their service.

At the same time, no carrier will have a fully integrated global low-cost residential network. Domestic carriers will therefore need to form virtual networks with rivals to develop a service offering that enables online retailers to ship to virtually anywhere in the world at competitive rates. Examples of such cooperative platforms include Kahala Posts Group, an alliance of national postal operators in ten large markets, and International Post Corporation’s e-Commerce Interconnect Programme, which aims to link 24 national postal operators into a fully interconnected network. We expect rapid growth in many types of collaborations, similar to those prevalent in the airline industry, where alliances range from code sharing to full mergers.

Integrators, for their part, have several options: building out a service from their preexisting networks of business-to-business clients, using their well-controlled backbones to connect senders with low-cost-delivery players, or building their own low-cost last-mile services to complete the final link of a seamless multichannel supply chain.

When cross-border e-commerce evolves to this level, every consumer will be able to shop globally at or near domestic service standards and prices. The retailers and carriers that hasten this evolution will be rewarded with significant growth.