The pressure on governments around the world to reduce deficits and public debt has been unrelenting. The response in many cases has been to cut operating costs, raise taxes, and slash investments. The potential downside to those moves, however, is sizable and includes delayed economic recovery and social unrest.

Another weapon in the government arsenal, however, has gone largely unused. Governments have not made a concerted and systematic effort to fully utilize and better manage the assets under their control, an approach known as asset optimization. Asset optimization may bring to mind steps such as divestments or privatizations, but they constitute just one piece of the puzzle. Beyond such one-time moves there are major opportunities for governments to aggressively manage the performance and maintenance of everything from roads to power plants and public museums.

The reasons for focusing on how government assets are managed are numerous and compelling. For one thing, the asset base is massive—the assets of many governments amount to trillions of dollars—and diverse, encompassing everything from physical infrastructure to valuable public data. Furthermore, unlike tax increases or budget cuts, asset optimization is not a drag on economic growth. And the political downside is limited, particularly when better management can yield improved service for the public and a better return on public dollars invested.

Just as important, asset optimization is eminently achievable in three steps: ensuring assets are operating at maximum capacity and efficiency, investing in those assets over their entire life cycle to minimize total costs, and generating additional revenues from those assets where possible. And while moving effectively on all three fronts requires focus and detailed planning, success is well within reach for most governments. The most challenging barriers to success are lack of attention to the opportunity and lack of commitment to making it happen.

An Untapped Opportunity

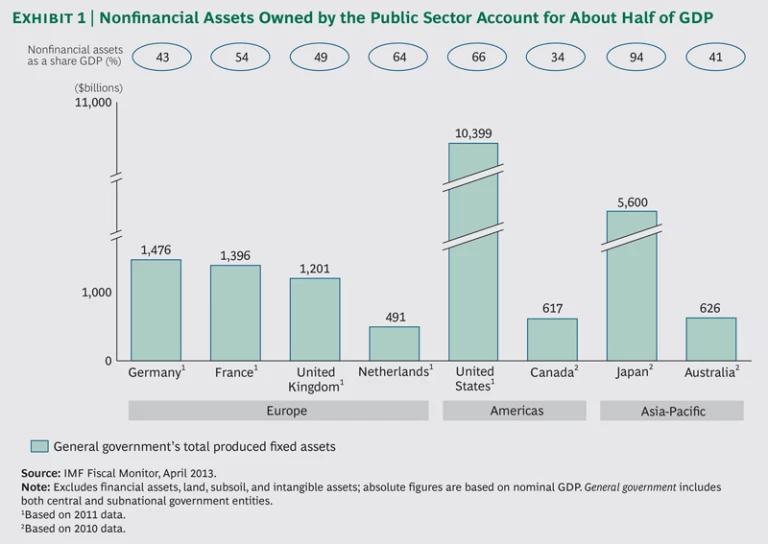

The potential benefits of asset-optimizing strategies stem in large part from the size of the asset base under government control. In major developed countries, according to the International Monetary Fund, nonfinancial assets owned by the government (including central and local authorities) can range from about 35 to more than 90 percent of GDP. (See Exhibit 1.) In Europe, that figure is about half of GDP.

In fact, these figures in many cases understate the scope of the opportunity. Land, mineral rights, landmarks, and intangible assets such as the brand names associated with popular government institutions, for example, are either not included in public balance sheets or are valued at low historical costs or nominal values. In addition, many governments hold equity stakes in domestic companies, and this gives those governments some degree of influence over an even larger asset pool. France’s central government, for example, holds roughly €300 billion (about $417 billion) worth of equity investments in various entities. Those entities, in turn, control more than €700 billion ($973 billion) of fixed assets, including major energy and transport infrastructure, real estate, brands, and patents—giving the French government influence over those

The benefits of wringing the greatest returns from those assets are significant. Such an approach can reduce operating costs and delay or eliminate entirely the need for new major capital expenditures. In addition, there are nonfinancial rewards. The quality of public services, for example, can be improved with fewer service disruptions while the government’s overall environmental footprint is being reduced. And the effort can result in streamlined, more efficient government operations.

Still, the potential to maximize the return on government assets has gone largely unrealized. Historically, official asset-optimization programs have been limited to privatizations and, in a handful of countries, to outsourcing. More recently, a number of countries have launched asset optimization initiatives, but, for the most part, they have focused narrowly on rationalizing government real-estate portfolios. In contrast, private-sector companies have used every tool at their disposal to wring the most benefit from their assets in order to maximize return on capital. These efforts intensified in the wake of the recent global financial crisis, as reduced access to capital made it increasingly critical to do more with the same—or reduced—resources.

There are several reasons for the public sector’s reluctance to push aggressively on this front. Some of the hurdles stem from the culture that exists within most governments. For instance, asset optimization is often erroneously perceived as reducing the quality of, or access to, certain services. In addition, because such efforts receive much less public attention than high-profile greenfield projects, many public-sector managers put less time and fewer resources into asset optimization. And there are significant human-resource obstacles as well, including a scarcity of internal asset-management expertise and a lack of powerful incentives for public employees to focus on maximizing the performance of government assets.

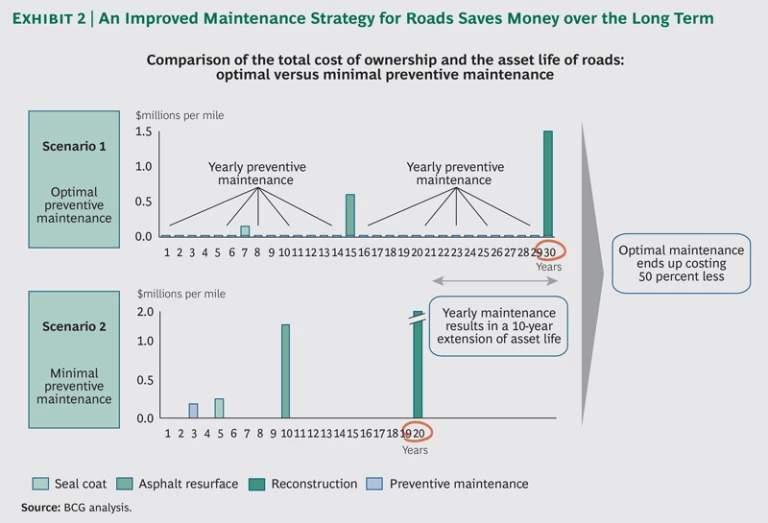

Furthermore, certain processes and incentives within the public sector tend to encourage short-term—rather than long-term—thinking. Budget constraints, for example, might make it difficult to hold maintenance spending steady in the near term even though such investments would save money over the course of several years. And government financial and accounting processes only exacerbate this short-term mind-set. Cash—rather than accrual—accounting is still the norm in most governments. That practice fails to give a detailed picture of the total cost of assets over their life cycle and essentially penalizes governments for up-front maintenance. In addition, separate budgets often exist for maintenance and investment, again undercutting the government’s ability to take a comprehensive view of all costs associated with a particular asset.

Wringing the Most Value from Public Assets

Government leaders are well versed in the issues associated with divestments, privatizations, and public-private partnerships. But they are less familiar with the mechanisms for improving the performance and returns associated with public assets. The three primary ways for achieving such improvements are operating assets in a way that maximizes their performance, investing in and maintaining assets in order to minimize the cost of those assets over their life cycle, and finding ways to generate new revenue streams from existing assets.

Maximizing Asset Performance. Underutilized assets—whether roadways, defense equipment, or Internet bandwidth—represent waste. In order to squeeze the best performance from an asset, governments must zero in on supply and demand problems that are leading to less than optimal functioning of that asset.

On the supply front, there are various tactics for achieving this. Implementation of new technologies and processes can eliminate bottlenecks and minimize service disruptions, and low-cost ways of increasing capacity can be explored before funds are pumped into building new capacity. Consider the efforts the UK government took in 2010 to rationalize its real-estate portfolio. Through staff relocation and office redesign, the Government Property Unit reduced the square footage of office space occupied by central government services by 12 percent compared with 2008, saving hundreds of millions of pounds.

Furthermore, demand can be managed to improve the performance of government assets. The goal: to smooth out peaks in demand and raise the average utilization rate for existing assets. In France, for example, when peak-hour toll fees on the A1 highway were raised by 25 percent, driving patterns changed and more traffic shifted to nonpeak hours.

Reducing Total Cost of Ownership. The key here is to carry out timely and appropriate maintenance, avoiding unplanned service disruptions—as well as the higher costs typically associated with emergency repairs—and extending the life of certain assets. At a U.S. city’s transportation authority, it was estimated that the implementation of systematic preventive road maintenance instead of a program of bare-minimum maintenance would lead to a 50 percent decline in annual cost-per-mile spending. The program offered the added benefit of extending the life of the roadways by a full ten years. (See Exhibit 2.)

Adding New Revenue Streams. The opportunity also exists for leveraging assets to generate much needed revenues. Among the possible actions: charging user fees, renting out excess real-estate capacity, offering consulting services, and licensing intangible assets. Major airports and railway stations, for instance, produce revenues thanks to the development of retail shops, services, and advertising space.

And while infrastructure and real estate are natural candidates for this sort of strategy (together they account for more than 90 percent of governments’ nonfinancial fixed assets), there are other opportunities for revenue generation that make use of tangible assets such as equipment (for example, medical-research systems) and intangible assets.

The Louvre Museum, for example, struck a 30-year brand-licensing agreement with Abu Dhabi authorities, a deal that will generate proceeds of €400 million ($556 million), the equivalent of two years of the museum’s budget. And the ever-increasing storehouse of data maintained by governments represents another potential source of significant revenues.

The Road to Execution

Public-sector leaders at the central and regional level—from defense agencies and energy ministries to transportation and infrastructure departments—can lead the charge to better public-asset management. Doing this is well within reach of governments, but to make it happen, they should first outline a comprehensive strategy. We believe that the following are the six critical elements of such a strategy.

Comprehensive Diagnosis and Multiyear Planning. The first step is to conduct a detailed examination of the assets under government control and to determine how management of those assets can be improved. This might require investment in certain light tools such as inventory databases. A multiyear plan should be developed, with various asset-optimization steps being studied through a scenario analysis that assesses the risks and benefits of each option. It might make sense to start by focusing on one piece of the government’s asset portfolio, testing new approaches, and learning from those trials.

The Right Team. Public-sector entities will need to expand their financial, commercial, and technical skills. These skills, which include long-term budget modeling and developing sophisticated demand and cost projections for assets such as roads, can be developed through internal training and partnerships with outside experts.

Clear Governance. Many groups play a role and have an interest in public-asset management. So it is critical to establish coordination among those groups to minimize both conflict and the duplication of efforts. Once a team has been established to steer the overall effort, that group should define a clear process for prioritizing projects, setting targets and milestones, assigning responsibilities, and keeping the channels of communication open between impacted groups such as public-service employees and government administrators. It also makes sense in some cases to enact rules that create incentives for collaboration among various groups. Among the possibilities: developing a mechanism for sharing cost savings from a new asset-management program among the various departments or ministries involved.

An Adjusted Budget Process. At the same time, the budget process might need adjustment to ensure that it will not discourage long-term maintenance planning and spending. Without that, managers are unlikely to propose an increase in maintenance investment, fearing that they might be required to reduce other costs to finance that spending.

Close Project Monitoring. Every initiative under the broad asset-optimization program must be expertly managed. The progress of each initiative should be tracked diligently, and select KPIs should be monitored regularly. For railways, for example, KPIs might include the daily use rate of trains or kilometers of railroad tracks renovated, and power plant programs might focus on utilization rates of those facilities.

A New Mind-Set. It is difficult to see an asset optimization push succeeding in the traditional public-sector culture, particularly given the persistent misconceptions about what such an effort entails. That’s why governments must embrace true change management. Initially, this involves mobilizing critical personnel to lead the program and requires building broad support for the effort, including winning buy-in from public-sector employees and communicating with public-service users to minimize possible resistance to change.

A strategy that incorporates these six elements is crucial. And the first step in achieving that is recognizing the tremendous untapped opportunity that exists in better exploiting government assets. That opportunity is a fact that public-sector leaders, facing the twin challenges of reining in public debt and spurring economic growth, can no longer afford to ignore.