A rising tide lifts all boats. A falling tide can just as easily beach them. For many companies in the casual dining restaurant (CDR) segment, current declining market shares, shrinking margins, and dwindling shareholder returns reflect familiar cyclical patterns that have long affected brands in this segment as well as other major dining segments. Changing consumer demographics and the continuing evolution of dining trends suggest that the tide for most CDR brands will continue to recede.

It’s premature, however, to write off the CDR segment as having lost its relevance. Consumers choose brands and experiences, not industry dining segments. There will always be brands that shrewdly navigate through shifting industry currents, attracting customers and retaining their loyalty—and doing so better than the competition. The leaders devise strategies to clarify or adjust (or occasionally reinvent) their brand experience in response to changing consumer preferences and needs.

This report examines the current trends affecting the U.S. CDR segment and the steps that CDR brands can take to remain relevant to consumers.

A “Reservationless” Recovery

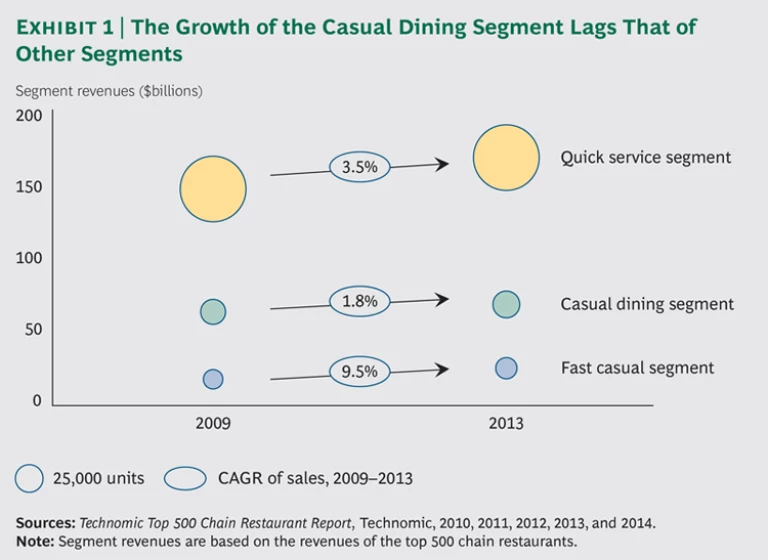

Like every business that depends on discretionary consumer spending, restaurants were flattened by the Great Recession. Since 2009, however, the U.S. restaurant industry has returned to historical growth rates, with total sales rising about 3 percent a year, slightly ahead of inflation. Sales growth was fueled by an increase in per capita spending on food away from home, which grew 2.5 percent per year from 2010 through 2013. But despite the broad industry recovery, the CDR segment has posted modest growth at best. Unit (or individual restaurant) growth, growth in average unit volume (AUV), and revenue growth in the CDR segment have trailed growth in the quick service restaurant (QSR) and the fast-growing

As a result, CDR brands have generally delivered inferior financial results when compared with brands in other segments. Many CDR chains have generated lower earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization, and rent (EBITDAR) and lower AUV-to-investment ratios than their newer, more modern FC counterparts. On average, CDR chains have also yielded lower unit-level returns on gross investment (ROGI) and lower five-year total shareholder return (TSR) relative to both QSR and FC brands.

The CDR segment is being disproportionately hit by long-term, market-wide shifts in consumers’ spending patterns. Three of the most significant shifts have been in the following areas:

- Health and Wellness. The strong and growing concern about health and wellness directly influences dining decisions. Consumers increasingly want food they perceive as healthy, fresh, and prepared with high-quality ingredients—not a traditional brand strength for most CDR brands.

- Breakfast. This is the fastest-growing segment of away-from-home meals, a trend most CDRs miss out on because they are not open.

- Free Time. Consumers’ free time is continually being compressed, as they are pushed to accomplish more in less time every day. Time constraints are accelerating growth in limited-service restaurants owing to their delivery models, which are more efficient than those of conventional full-service establishments.

In addition to these shifts, most CDR brands face a big challenge turning one-time visitors into regular customers. Our research shows that while QSR chains convert about 15 percent of first-time guests into regular visitors, and FC restaurants convert more than 18 percent, the conversion rate for CDRs is only 6.5 percent. A few brands do better, winning up to 10.4 percent, but even they fall far short of the QSR and FC averages. This implies that CDRs must work up to three times harder to convert first-time customers into regular guests.

Despite these issues, we do not believe that casual dining has lost its relevance. In fact, full-service dining is alive and well. But not all brands are equally vigorous. Over the past half century, the restaurant industry has experienced multiple waves of segment growth and contraction. With each wave, new brands have emerged to meet evolving consumer trends, and existing brands that have failed to respond or innovate have declined in popularity, as competition and shifting consumer needs eroded their differentiation.

Slow Growth Is a Segment Fact—and a Brand Challenge

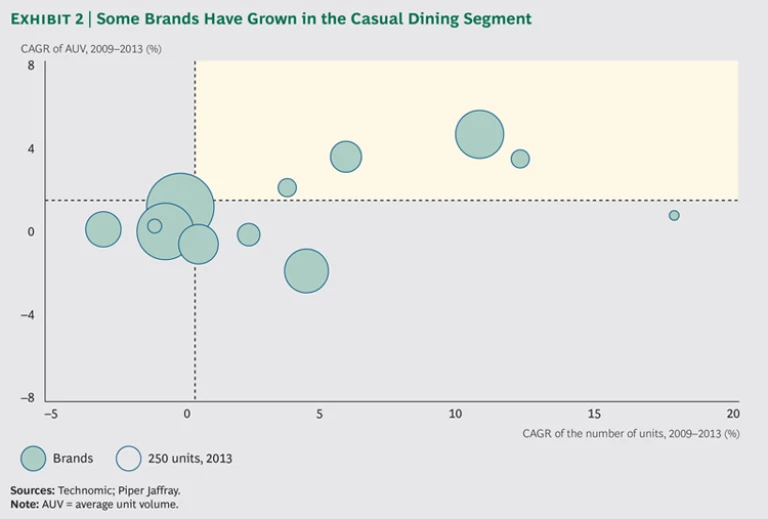

A drawback of segment-wide analysis is that it can conceal significant variations in performance among individual brands and companies. And indeed, in the CDR segment from 2009 through 2013, several brands outperformed, increasing both their unit count and their AUV. (See Exhibit 2.) There was a spread of 35 percentage points in 2013 ROGI among CDR brands, with the leaders producing returns ranging from 35 to 40 percent. Similarly, the segment had a variation in annualized TSR from 2009 through 2013 of 45 percentage points, and several companies delivered annual returns of more than 35 percent.

Multiple indicators support the view that the CDR segment is at another historical inflection point, with older brands that have not maintained differentiation fading and newer players rising to take their places. Word of mouth, for example, is a big influencer of restaurant traffic. The BCG Brand Advocacy Index measures this critical metric by using a method that has a high correlation with

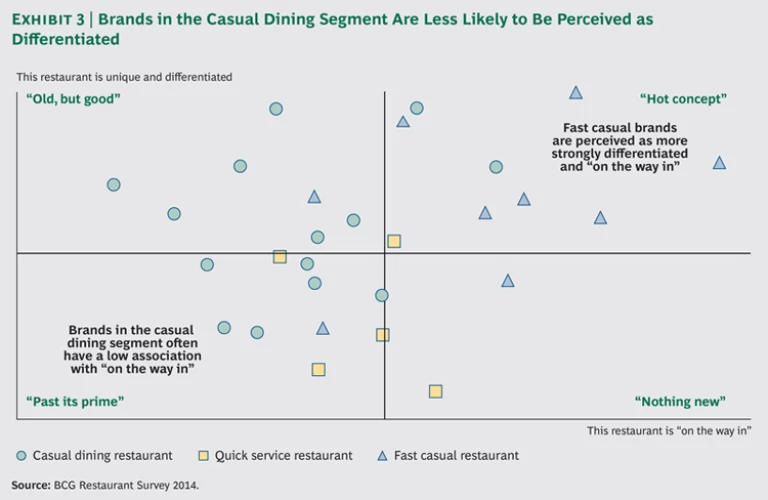

In addition, consumer perception affects differentiation and brand momentum. Although many industry observers believe CDR brands to be largely undifferentiated today, our research shows that in the eyes of consumers, there are significant variations, with several CDRs competing strongly with FC chains. (See Exhibit 3.)

The CDR segment faces a challenge attracting Millennial consumers, who are significantly more likely than their parents (or grandparents) to choose a QSR or an FC restaurant. Our 2014 restaurant survey shows that the average number of annual restaurant visits made by Millennials exceeds the average number made by non-Millennials by 12 percent. But once again, there is significant variation among brands in the CDR segment, with some restaurants getting more than 40 percent of their visits from Millennial consumers—far above the average of 23 percent for all CDRs.

On the basis of this analysis, we believe that it is more useful to ask not about category relevance but whether each individual brand is positioned for sustainable success—the key to growth—and whether it has a winning strategy that will enable it to compete effectively.

The hurdles for CDR companies are high: adverse trends, changing tastes, new sources of strong competition, and tired brands. The traditional fixes that restaurants employ in the face of slowing growth, such as revamped marketing, increased promotional activity and value offers, and scale-building mergers, are unlikely to solve, and may even exacerbate, the problems. CDR companies looking to improve their business trajectory need to identify opportunities to push their brand evolution in directions that respond to current consumer trends.

The good news is that many CDR players have strong brand attributes that resonate with consumers. The challenge is determining how to use these attributes to tap into evolving consumer needs. Working with multiple clients in the retail, consumer goods, travel, and hospitality sectors, BCG has developed a process for doing just that. (See Brand-Centric Transformation: Balancing Art and Data, BCG Focus, July 2011.) Brand-centric transformation starts with an understanding of the factors that affect consumer choice.

The Impact of Emotion on Choice

Consumers consider a variety of factors when choosing a restaurant to visit. These factors include the local competition, the available brands, the circumstances surrounding a given visit (the time of day, type of occasion, and time constraints, for example) and individual preferences (such as the type of food and atmosphere). But our research shows that a consumer’s emotional “need states” are the biggest dynamic affecting his or her decision. An emotional need state describes something consumers want to feel during a restaurant visit and, therefore, what they expect the restaurant to deliver. Research shows that consumers visit a given restaurant more frequently when they are satisfied that the brand meets their need states.

It’s impossible, of course, to win 100 percent of a customer’s business; too many factors come into play. Moreover, the tactics that a company employs to win some visits create a brand experience that may conflict with a customer’s requirements for other visits. The processes and techniques that deliver a fast experience, for example, are unlikely to create an environment that resonates with a customer when he or she is seeking to relax.

But—and this is a critical “but”—it is entirely possible to win more business by segmenting a market on the basis of visit-specific need states and a brand’s ability to meet them. Need states provide a vital lens through which companies can analyze consumers’ behavior and develop an action plan for restaurant growth.

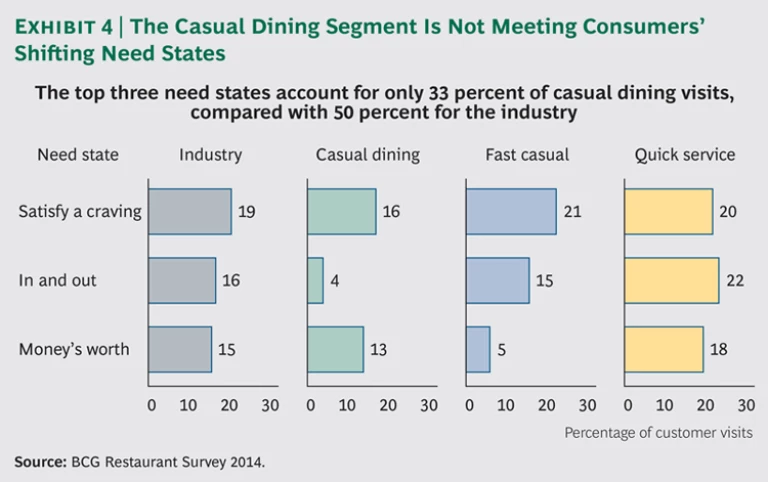

In our experience, there are 12 core need states that affect consumers’ decisions across all three restaurant-industry segments. The three most common need states—satisfy a craving, in and out, and money’s worth—determine 50 percent of all restaurant visits. By contrast, fill me up, which is eighth on the list of need states, accounts for only 6 percent of visits.

To attract customers on the basis of a single need state, a brand must have credibility for addressing that need state. Consumers must believe that a brand meets a need in order for them to choose the brand when that need state is the primary determinant. A successful brand can carve out a differentiated market position in a single need state, such as in and out, or a combination of complementary need states, such as quality ingredients and healthy choices. The most successful restaurant brands have established differentiated positions in the top need states. But regardless of where it is starting from, a restaurant brand can improve its growth prospects through this segmentation analysis. For brands that are already strongly differentiated, this exercise can reveal complementary need states through which a brand’s existing capabilities can help it gain market share. For brands that lack a differentiated position, analyzing the market in this way can point to areas in which brands could build a stronger presence by using current capabilities or by developing new ones. (See “Arby’s: Putting an Icon Back on Track.”)

ARBY'S: Putting an Icon Back on Track

In 2010, the iconic QSR brand Arby’s was suffering from chronic declines in same-store sales and growing irrelevance. Consumers were questioning the brand’s quality and value and passing over its long-loved roast-beef sandwiches for other QSR and FC options. The company’s relations with its franchisees suffered because of poor financial performance, a perceived lack of strategy, and management turnover. The complexity of the chain’s menu added operational challenges. Meanwhile, other QSR companies were experiencing a return to growth as the economy began to improve after the Great Recession.

By applying a brand-centric transformation approach, Arby’s leadership identified two common consumer need states—I know it’s fresh and hits the spot—that the brand had the strength and the ability to successfully address. Then the company reassessed its brand-benefit ladder and implemented a series of initiatives to deliver a brand strategy that targeted these need states. The strategy included changes to the menu that were rooted in freshness, simplification, and value; a redesign of its physical locations; and a new creative communication and marketing campaign. Arby’s brand strategy celebrated the heritage of the brand with an updated look and feel; built on the tradition of sliced meat by expanding into other, unique sandwich-product offerings; and sought to educate consumers on the quality and variety of meats and other ingredients that were freshly prepared in the restaurants.

By addressing the combination of need states, Arby’s was in a position to differentiate itself in a way that few, if any, of its competitors could match. Arby’s recovery began almost immediately, and the brand has outperformed its peers on a sustained basis for several years. From 2011 through the second quarter of 2014, same-store sales have grown at a rate of 2.5 to 4.5 percent a year, compared with the QSR segment average of 0.1 to 0.3 percent over the same period.

Arby’s brand transformation illustrates the power of a brand-centric approach to identify new avenues of growth and imbue revitalized energy into successful brands that for many reasons find themselves stalled.

Consumers’ need states are dynamic, of course. The importance of each need state rises and falls over time, and new need states also come into play. Currently, a widespread concern about health and wellness means that health-related need states are growing in importance. (See “Shifting Requirements in Health and Wellness.”) Because of the time pressure consumers feel in their daily lives, in and out will continue to be an influential need state.

SHIFTING REQUIREMENTS IN HEALTH AND WELLNESS

As consumers’ focus on health and wellness continues to increase, we anticipate the ongoing evolution of health-focused need states and the opportunity for best-in-class innovation to fuel growth for forward-looking brands.

The restaurant brands that have positioned themselves to satisfy these need states have captured a bigger share of diner visits and are growing. The FC segment’s growth is fueled by multiple brands that have successfully addressed five of the top need states, including several increasingly popular need states, such as quality ingredients and satisfy a craving. Numerous brands in the QSR segment have significant credibility for meeting the top three need states and the in and out need state, in particular.

The CDR segment’s performance is significantly below average when it comes to meeting the most common need states. The top three need states for the industry account for about only one-third of customer visits to CDRs, compared with 50 percent of visits for the industry as a whole. (See Exhibit 4.) CDR’s own strongest need state—share good times—accounts for only 5 percent of all visits. Moreover, CDR has little credibility addressing the need states that are fueling growth in the market, especially those that are related to health and wellness.

That said, although many CDR players have not changed their strategy or approach to meet consumers’ shifting need states—leading to the segment’s overall stagnation—a few players have built strongly differentiated positions by addressing the most common consumer need states. For example, Buffalo Wild Wings, The Cheesecake Factory, and Texas Roadhouse have built strong positions by addressing the satisfy a craving need state. In addition, The Cheesecake Factory has credibility and share in a less common need state, quality ingredients, and Texas Roadhouse has strength in addressing a less common, complementary need state, fill me up. For BJs, strength meeting one of the top need states, in and out, provides differentiation. These companies are growing significantly faster than average as a result.

It’s About Much More Than Marketing

Understanding consumers’ need states and positioning a brand to target them are the first steps to unlocking growth. But to establish a credible, differentiated position, as well as a winning brand strategy, a restaurant chain must deliver the benefits of the need states that are of greatest importance to consumers. Delivering these benefits requires more than a marketing campaign. A company first needs to clearly articulate a brand ladder that establishes the technical, functional, and emotional benefits of the brand so that consumers can readily grasp and appreciate them. (See “The Brand Benefit Ladder.”) Second, a company should construct a brand strategy that focuses the entire organization on delivering the technical attributes that make a difference to consumers for the targeted need states. (See Exhibit 5.)

THE BRAND BENEFIT LADDER

A data-driven approach to brand transformation requires that executives first understand what affects consumer choice in the product category and then translate that understanding into the core elements of the brand. To accomplish this, we rely on the “brand benefit ladder,” a tool commonly used by marketers to describe how specific product benefits layer to support one another in delivering a brand experience to the consumer.

Our basic brand-benefit ladder has the following elements:

- Technical attributes include physical characteristics of a product or service, such as the ingredients, quality level, or aesthetics.

- Functional benefits describe differences in how the product or service features are experienced and used by the consumer.

- Emotional benefits capture the feelings inspired by the product or service.

Although technical attributes and functional benefits can vary among brands, they are not sufficient on their own to provide sustainable brand differentiation; ultimately, emotional benefits are the key to creating customer loyalty, preference, and willingness to pay.

Every successful brand has a brand benefit ladder that is relevant, differentiated, and fully experienced by the consumer. For example, travelers on Southwest Airlines feel thrifty and savvy because of rock-bottom ticket prices and no-frills service offerings delivered by high-energy employees. BMW owners feel proud to drive a superior performance vehicle grounded in German engineering. Starbucks customers feel self-indulgent when they consume the company’s high-end Arabica coffee beans and handcrafted beverages.

But simply using the brand ladder as a tool in brand strategy efforts doesn’t prevent suboptimal branding decisions. Unfortunately, marketers tend to consider only the emotional layer of the brand ladder and do not apply the necessary rigor in quantifying and fully understanding the links that connect the technical, functional, and emotional layers. In many cases, they also fail to use hard data to measure the value of potential brand investments and to prioritize trade-offs. Finally, they struggle to implement the resulting brand-ladder elements and hold the organization accountable. Although the brand ladder is an important—and highly useful—tool, it is only one component of a larger brand-transformation program.

Regardless of the need states a company decides to target, it must fulfill the requirements that are important to all consumers at all times. These table stakes include fundamentals such as restaurant cleanliness, product quality, employee friendliness, and timely service. While there is little upside to overdelivering, brands risk strong negative reaction if these basic requirements are not met.

Beyond the table stakes, a company must build credibility for meeting the need states that it is targeting by delivering the technical attributes that matter most to consumers for each state. The quality ingredients need state requires ingredients to be consistently fresh and of high quality, for example. In and out depends on quick service. The money’s worth need state is all about consumers feeling that they receive good value for the price they pay.

There is significant upside potential for brands that successfully meet consumers’ need states—and there is an equally significant risk of dissatisfaction if consumers’ expectations are not met. Companies need to execute effectively—and perhaps much differently than they have in the past—across a wide variety of functions, including the following:

- Menu. Tailor the menu architecture to focus on items and product categories that are appropriate for the target need state.

- Pricing. Match pricing strategy to the target need state.

- Communication. Reinforce technical attributes and emotional benefits through in-store and out-of-store marketing.

- In-Store Experience. Design the physical environment and service model to support the brand position.

For example, when targeting the in and out need state, successful brands work to deliver better quality food more quickly. They build their menu options around takeout and delivery. They invest in technology and process innovation to deliver consistently fast service. And they evolve their physical footprint with format innovations, such as drive-through and express services or small-format stores.

In a similar vein, brands that want to have credibility addressing the quality ingredients need state reinforce consumer perceptions of freshness, high quality, and healthfulness. A company’s priorities may include expanding its assortment of fresh products and emphasizing locally sourced ingredients; communicating consistently in store, out of store, and online about its ingredients and approach to preparation; and redesigning its restaurants around an open kitchen or other visible food-preparation area.

Even brands with long-standing systemic shortcomings in addressing common need states are seeking to increase market share by investing in innovations that strengthen their credibility. For example, some CDR chains are using tablets to increase the perceived speed of the experience (in and out) and QSR chains are emphasizing ingredient quality and product healthfulness in their food preparation and marketing (quality ingredients). (See “An Interview with the Chairman of Ziosk.”) Moreover, to maintain competitive advantage, companies need to monitor and adapt to the continuing evolution of technical attributes.

AN INTERVIEW WITH THE CHAIRMAN OF ZIOSK

Jack Baum is chairman and cofounder of Ziosk, the restaurant industry leader for tabletop ordering, entertainment, and payment in the U.S. He recently discussed his perspective on the challenges facing the CDR segment and how technology is helping some brands find growth.

You have been working in the restaurant industry for years, first as an operator and now as a technology partner. As a restaurant operator, how did you think about growth?

Growth is always on the minds of restaurant executives, but, at times, it can feel like an abstract pursuit. There are two perspectives that I’ve found helpful to make growth something actionable.

First, for a restaurant to achieve growth, it needs to earn only one additional trip from current customers every 60 days. Casual dining is a low-frequency segment—for some chains I’ve worked with, customers may visit only once every 49 days. That means for every 98 lunch and dinner trips customers could be spending in my restaurant, they are choosing to spend only 1. If I capture even 1 more of those 98 trips, I double my traffic. I don’t have to win against my strongest competitor to grow. I need to capture only 1 trip from my weakest competitor.

Second, investing in improved customer satisfaction will have a higher return than any other investment I can make. When customers are more satisfied with the experience we’ve given them, they visit more often and advocate more strongly for my brand. This means that what I do inside the store to deliver the best experience is critical for growth.

What are some of the greatest challenges you see facing CDR brands today?

CDRs are facing challenges in all core elements of their business: food, service, atmosphere, and location. Of course, there are clear market pressures, such as rising commodity prices and minimum wage rates. But there are also structural challenges within the business model that impact growth.

Thinking about food, for example, brands often have limited visibility into guest satisfaction with individual menu items. As new items are introduced and promoted, an initial customer trial might yield strong early-sales volumes. But management won’t know until a customer’s next visit—remember that’s 48 days later—whether he or she liked the item enough to purchase it again and whether the item will sustain sales over the long term. This delay makes it very challenging to manage a menu and the mix of items to maximize guest satisfaction and profitability.

With service, management teams face a similar information gap. They don’t know whether a customer’s experience was positive or negative, as very few customers provide direct feedback on the service. And when they do, it typically comes in the form of a customer satisfaction survey, completed after the trip is over and when it is too late for management to resolve the issue.

For many established CDR brands, the store atmosphere has become dated and is not well targeted to Millennial consumers. But with compressed margins and declining cash flows, costly investments in the physical space become hard to justify. Management teams face a similar challenge with store locations. Many stores that were originally located in “A” locations now find themselves in “B” or “C” locations—compounding the existing challenges of driving traffic.

What are strong brands doing differently to find growth in the face of such challenges?

Although the market dynamics are difficult to control, brands in the CDR segment can influence internal operations to mitigate these challenges. The most successful brands are those that have focused their efforts on customer satisfaction throughout the entire experience.

For example, brands often focus their marketing and communication efforts on engaging consumers outside the restaurant. The most successful brands also engage their teams and build excitement and advocacy for the brand. This enthusiasm results in better service, higher satisfaction, and more frequent visits.

How has Ziosk helped your clients tackle the challenge of growth?

The idea for Ziosk grew out of a consumer need that we saw in the market. Research showed that 68 percent of customers’ complaints were related to not being able to pay when they wanted to. By placing a seven-inch tablet on the table to accept payment at the customer’s convenience, the restaurant could increase the level of satisfaction and the frequency of visits.

As restaurants began implementing our tablets, we found that they not only resolved customer complaints about waiting for the check but also addressed some of the other challenges we’ve discussed. Concept teams could get customer feedback on new menu items in real time, allowing them to project sales volumes beyond the introductory period. Store managers could identify and resolve any service issues while the customer was still at the table. And servers could spend more time with their guests, focused on increasing satisfaction (and receiving a better tip) rather than on administrative tasks. Employee retention soared and the servers’ new attitude also went a long way toward improving the experience of their guests. Ziosk tablets also allowed guests to stay entertained and restaurants to engage guests in new and exciting ways.

As Ziosk tablets have been rolled out in more and more chains, our clients are seeing measurable financial impact. Guests at a table with a Ziosk tablet order more beverages, appetizers, desserts, and even coffees. Servers are able to turn tables more quickly. And, overall customer satisfaction increases, which means more frequent visits, higher revenues, and stronger margins.

Success Requires a Strong Action Plan—Backed by a Team Effort

In our experience, executing a differentiated brand strategy successfully requires an action plan with three core elements.

End-to-End Engagement Across the Organization. No brand transformation can succeed without the full support and engagement of top management, of course. But in CDR (as well as other restaurant segments), brands may have thousands of stores, with many operated by franchisees. We cannot overstate the importance of getting the entire organization involved to ensure that all functions act to support the new brand positioning. This may require promoting new ways of thinking and reorienting the corporate culture around new aspirational pillars. A top executive priority should be consistent execution that extends from the strategic priorities set at the corporate office to customer-focused activities at the stores—the activities that deliver the consumer experience.

A Disciplined Assessment of Investment Trade-Offs. Capital and human resources are always limited. Companies need to determine which investments can generate the best return on investment (ROI), on the basis of the consumer need state the brand is seeking to meet. Because investments can be large, many companies opt for a test-and-validate approach, market-testing low-cost to high-cost prototypes to validate their ROI before full-scale capital campaigns are undertaken.

A Well-Managed Implementation Timeline. In our experience, the required time frame to complete an effective brand transformation can be up to three years, although the benefits can start to flow much more quickly. Companies typically find the quickest impact is realized by addressing gaps in the fundamental requirements that are important to all consumers at all times and by improving communication of the technical attributes the brand is already delivering. Larger changes to menu, pricing, operating model, and physical environment often require significant capital investment and time, but, if smartly executed, such changes can deliver commensurately greater benefits. It’s important for management and the organization to establish a timeline and have clear milestones, interim objectives, and designated “owners” for each strategic initiative to ensure accountability for success.

A Five-Point Framework for Growth

CDRs can pull out of the current state of stagnation and return to growth. But doing so requires looking at the marketplace differently and adopting a more sophisticated, more aggressive approach to brand management. The following five steps will put any company that pursues them with rigor and discipline onto a road to accelerated growth and a more profitable future.

- Get to know the market, not only the customers. Build an understanding of the need states that cut across consumer segments.

- Consider opportunities to pivot the brand toward more common need states in the market. Assess the brand’s ability (which is different from management’s desire) to build credibility in these need states.

- Invest in research to understand the physical cues (such as the place, product, and people) that tell consumers they will find what they are looking for. Translate these cues into prioritized investments in menu, pricing, communications, service, and physical environment.

- Ensure that the brand vision is clearly articulated to the management team and the field staff. Engage the organization broadly in the strategy, tactics, and execution. Avoid approaching transformation as primarily a marketing function.

- Filter everything through the revised brand positioning. Maintain a relentless focus on the brand positioning and use it to evaluate and reprioritize investments on an ongoing basis.

Sailing against the current is never easy. But the reward can be staying afloat—and being well positioned to catch the next rising tide.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Allan Hickok for his insights and assistance in the preparation of this report. The authors also thank James Cooper and Jun Han for their help with the research.