As omnichannel retail increasingly moves from concept to reality, consumers are sending a clear message: Convenience is king. But the days when convenience could be defined solely in terms of drive times and the in-store experience are long gone. In today’s reality, “convenience” means letting customers decide when, where, and how to shop. They want to order anytime, anywhere, and from any device; to get their purchases in the store, at a separate delivery location, or through home delivery; to determine their own shopping and delivery or pick-up windows to fit their busy schedules; and to be able to return items at any of the store’s retail locations, hassle-free.

The Rise of Click-and-Collect Retail

The emergence and growth of click-and-collect retail—which allows shoppers to order an item online and then go get it at a nearby store location or pick-up point—is evidence of the power of convenience in the omnichannel world. For many shoppers, the click-and-collect experience offers a more convenient mix of speed, quality, and flexibility than either traditional shopping or standard home delivery.

Already, 35 percent of shoppers who buy items online have used click-and-collect retail to pick up their purchases, and that proportion will increase to more than 75 percent of shoppers by 2017, according to retail researcher Planet Retail. Shoppers in France can pick up their groceries at more than 2,000 “click and drive” facilities. On the basis of our experience with leading retailers, we expect substantial growth in the use of such services.

Done right, click-and-collect retail can be a way for brick-and-mortar retailers to differentiate themselves from pure-play e-tailers by leveraging their existing store assets to offer fast delivery, low prices, and even greater convenience. That’s why many traditional retailers are eager to capitalize on this opportunity.

But click-and-collect retail can also pose real risks for retailers that fail to execute it flawlessly. A recent survey by market researcher E-consultancy.com found that as many as 60 percent of online consumers in the UK and U.S. said they would not shop at retailers that failed to deliver on their promises. This is as true for click and collect as it is for home delivery—particularly when it comes to apparel, a sector where customers expect to pick up the exact size and color they ordered and not a close substitute. In a hypercompetitive retail environment, an annoyed customer is likely a lost customer.

Supply Chain Imperatives

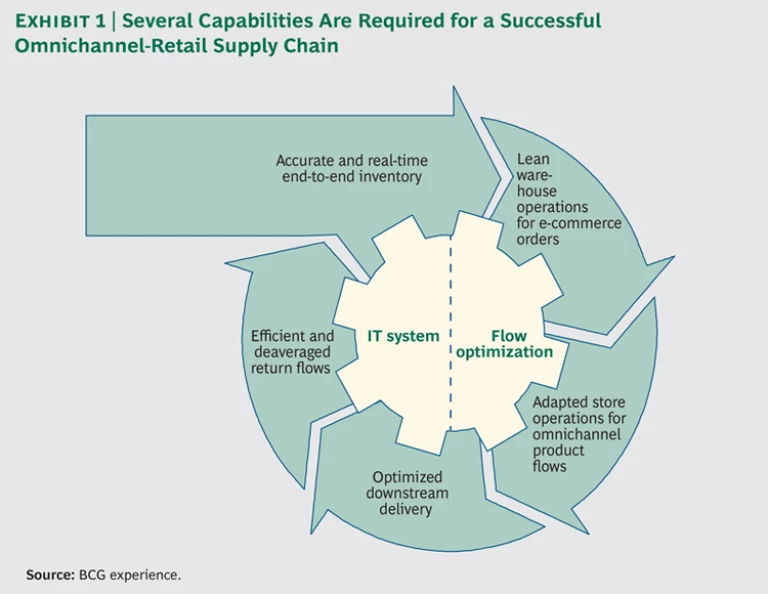

So, for retailers that seek to make click-and-collect retail a core component of their omnichannel-retail strategy, many specific supply-chain capabilities are required. (See Exhibit 1.) All are important, but in our experience, it all begins with providing shoppers—and store associates—with accurate, real-time information on product availability.

One way to manage this critical capability in a click-and-collect retail environment is to deliver the customer order from a distribution center to the store, as UK retailer John Lewis does. Centralizing click-and-collect fulfillment in distribution centers concentrates and simplifies the inventory management challenges. But it also adds precious time to the order-to-pick-up cycle, putting off impatient customers who might simply buy the item elsewhere next time. And many retailers’ legacy distribution networks are ill equipped to fulfill customer orders from existing distribution centers, which are typically designed to pick large orders for stores. For many retailers, then, a better solution is to pick click-and-collect orders from store stock. But getting the basics of in-store inventory management right presents a real challenge in terms of meeting customers’ expectations about availability. In our experience, a store’s balance-on-hand accuracy can be as low as 60 percent, which would be disastrous for click-and-collect customer satisfaction. Search online for “click and collect” for many big-name retailers, and you will see a slew of messages from customers describing poor experiences and products not being available when buyers turned up to collect them, even though the website had indicated that the goods were in stock. That’s why at Best Buy, for example, clerks physically doublecheck the availability of every item in every click-and-collect order in the stores themselves to overcome unreliable in-store inventory.

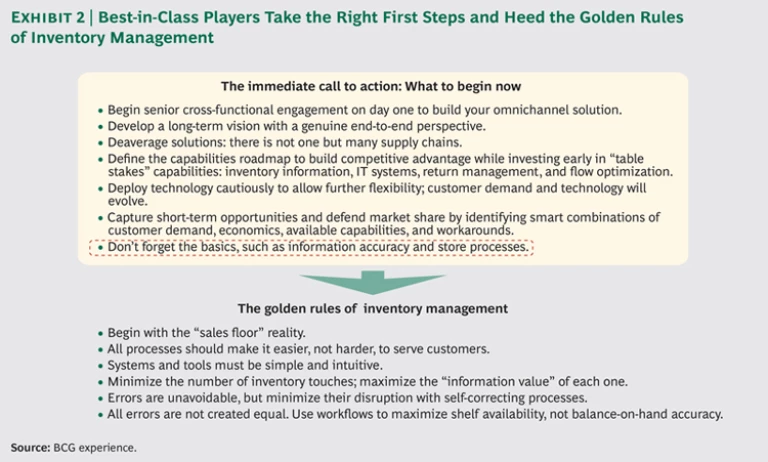

Why the poor performance? In support of their initial omnichannel offers, many retailers have chosen to focus first on building new infrastructure—pick-up points, distribution centers, delivery networks, IT systems, and even new stores. No doubt, these solutions can be critical components of a successful long-term omnichannel strategy, but getting the basics right, including in-store inventory, is often the most important first step to creating immediate impact and options for the future.

Back to Basics

Best-in-class players focus on making in-store processes efficient, rigorous, and self-correcting; their processes are consistent with our six “golden rules” of inventory management. (See Exhibit 2.) No IT system can account for products mistakenly left in the back room, inaccurate distribution-center deliveries, removal of damaged goods from shelves that is not captured by the inventory system, check-out errors, and theft. These unavoidable issues, and their consequences, must be accounted for and captured, accurately, by the inventory system. This often needs to be done by a real person, properly incentivized and managed. Ideally, every touch of inventory at every point in the process should validate, correct, or improve inventory accuracy. In our experience, major retailers with such self-correcting systems and processes can achieve balance-on-hand accuracy of greater than 95 percent; at that level, the impact on items popular with customers is marginal.

Building such an approach, however, requires getting all the details right: understanding where errors occur, why they occur, and what solutions can be implemented consistently and effectively by store employees. In this endeavor, the devil really is in the details. Eventually, emerging technologies will likely become a key part of the solution as well. Radiofrequency identification, or RFID, for example, has the potential to dramatically improve the accuracy of the information that supply chains depend on. Unfortunately, the ability to tag individual items economically and to scale up the technology to the needs of large retailers is still several years away. In-store cameras are a promising alternative for monitoring store stock, but they will require further developments in high-quality processing and image recognition if they are to make a difference. But even the most advanced technology will never entirely substitute for the disciplined in-store behavior needed to drive true inventory accuracy.

Thriving in an omnichannel-retail environment will require a host of different fulfillment capabilities. Retailers must design and execute the best possible customer service across all retail channels, build the infrastructure needed to ensure consistent pick-up and return processes, and continually capture and analyze the data needed to understand their customers and customers’ expectations of each channel so that stocking and flow strategies can be adjusted accordingly.

But that’s a longer-term goal. Near term, retailers that seek to capture their fair share of the growth in click-and-collect shopping should focus first on getting the basics of stock accuracy right. Doing so will deliver near-term benefits to the bottom line and position them for success, no matter what omnichannel strategy they decide to pursue.