To their surprise and dismay, many companies discover that IT outsourcing doesn’t always go as planned. Indeed, disappointments abound, with engagement after engagement failing to deliver the expected savings, improved service quality, and greater business agility. (See “ IT Outsourcing: Expectations Versus Facts ,” BCG article, March 2013.) Relationships with providers can be frayed or outright dysfunctional, with disputes and bickering continuing until the agreement runs its course.

Little wonder, then, that looking for lessons in failed engagements has become a virtual pastime for the IT sector. Yet the disappointments continue. So perhaps it is time to draw insight from how another sector sources work—and does a better job of it. An ideal candidate is the automotive industry.

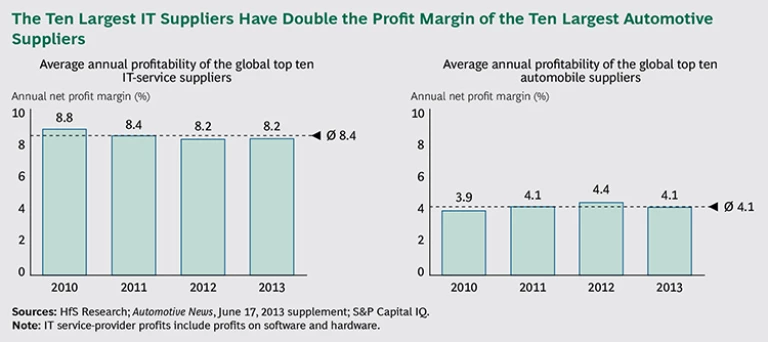

Carmakers delegate as much as 80 percent of their production to suppliers, and they’ve had decades to perfect relationships and practices. They’ve been remarkably successful, spurring innovation, cost reduction, and new efficiencies from their external partners even after the contract is signed. Automakers have created—and leveraged—an environment in which suppliers are continually challenged to deliver better products and processes. And they deliver them without supersizing the tab: profit margins for the ten largest automotive suppliers averaged 4.1 percent between 2010 and 2013. (See the exhibit.) Compare that to IT, where during the same period, the top ten providers enjoyed more than double the net profit—8.4 percent—yet didn’t necessarily see their customers raving about the value they added.

To be sure, not even automakers have a silver bullet for optimizing sourcing. Approaches can vary, from long-term collaborative relationships with suppliers to a more “transactional” model emphasizing price. From among these approaches, we have identified four key strategies that have particular relevance for the IT sector:

- Retain expertise.

- Pay special attention to processes that can give the company a competitive edge.

- Continually challenge suppliers to deliver improvements.

- Ensure transparency on costs and performance.

Using these strategies, companies will find themselves far better able to foster innovation and efficiency in their IT-sourcing engagements. Just as important, it will spur them to manage IT as a core component of their business—and a key ingredient of its success. Because in a wide range of sectors, from banking to insurance to logistics, that is increasingly what IT is. You wouldn’t know it, however, from the way many companies treat their IT sourcing, which is often still seen as a supporting player. Even automakers don’t always give IT sourcing the attention they give to the procurement of vehicle parts. This second-string status may have sufficed in the old days, when IT wasn’t “what the business is about,” but not anymore.

Retain Expertise

Automobile manufacturers understand that when you know what a component does (or should do), how it fits with your business goals, and what it should cost, you make better decisions about what to buy, whom to buy it from, and what to pay. They realize, too, that it’s important to see the big picture—how different parts and systems should be integrated. Accordingly, carmakers have been very careful to retain their expertise—no easy feat when more and more tasks are delegated to others.

How do they do it? One way is by keeping the production of certain parts, or even just a portion of production, in-house. BMW, for example, produces some car seats, as well as some parts for the drivetrain and other systems, internally. Another approach is to produce new technologies in-house initially—before sourcing them later on—in order to better understand them. Either way, the knowledge that carmakers gain lets them challenge partners on processes, quality, and pricing. It also lets them home in on new trends and suppliers that might prove valuable down the road.

No doubt, it can often be more cost efficient to source this work than to do it internally, but for automakers, the added cost is an investment. The experience of IT organizations proves their point. A lot of companies have outsourced so many core IT capabilities that their expertise in—and ability to assess—the services that they buy is limited. This information imbalance between buyer and seller often gives providers leeway to boost prices or sell services that may not be the best fit for a company’s needs. To put it simply, customers just don’t know how, or even if, they could do better.

Rebuilding expertise won’t happen overnight. But there are steps companies can take to get on their way. They can look at their roster of outsourced services and see which could be taken back in-house. That’s an approach GM has taken with its IT processes, re-insourcing a significant amount of work. Meanwhile, whenever new tasks are flagged for possible outsourcing, the company should consider the knowledge to be gained or retained by leaving it—in whole or in part—in-house. For example, companies that have outsourced testing to a third party need to integrate this activity into their Scrum teams when moving from waterfall to agile software development. Technical experts can also be put on procurement teams in order to better analyze provider capabilities and offerings.

A particularly helpful step is to prioritize emerging key technologies, gradually building skills in areas like virtualization and the cloud—whether by hiring talent from the outside or dedicating resources to develop it within. Companies should take note, though, that new skills often need to be managed in new ways. Employees coming from entrepreneurial environments, for example, may be accustomed to rapid development cycles, continual challenges, and a career track based on skills and ability instead of seniority. Similarly, IT sourcing and vendor management must become an integrated part of an IT career path and not treated as an end station, as is sometimes the case.

Pay Attention to Processes That Can Provide an Edge

Automakers are also careful to avoid a one-size-fits-all approach to sourcing. For parts that are used with little or no differentiation across carmakers, the emphasis is usually on getting the best price. But for components that can help a vehicle stand out from the competition, the focus—and the company’s interaction with its suppliers—becomes more nuanced and more hands-on. There may be more collaboration or joint development, or simply more guidance and input from the automaker.

Of course, the areas that get flagged for special attention will vary. Some premium European brands, for example, view the lighting system as a differentiator and have been working closely with suppliers to bring out innovative offerings such as laser headlamps. But in all cases, the idea is the same: not all sourcing engagements are equal. It’s okay to have a favored son.

This is in stark contrast to how IT sourcing typically works. Whether a process is a “differentiator” or a more commoditized task, it tends to be handled in a similar hands-off way, with the company agreeing to a price and relying on the vendor to get things right. Instead, companies should be identifying those processes that can set them apart and how IT supports them. For instance, for a logistics company, one differentiating process might be the routing of its trucks, which IT may support through a specialized software application. This is an application whose sourcing should be flagged for special treatment, which can take the form of more hands-on involvement, more collaboration or joint development with the software vendor, and more supervision.

Challenge Suppliers

Perhaps the most crucial strategy automakers employ is to continually challenge suppliers to improve performance and lower costs. They do this in a surprisingly simple yet extremely effective way: by ensuring that there is another supplier in the wings. Multiple suppliers are asked to present prototypes early in the design phase, and multiple suppliers are selected for further development. As production draws near—perhaps a year out—yet another vendor is added to the mix and asked to try its hand at a component. Even during actual assembly, dual sourcing is common. There is always someone else to whom the automaker can assign some of the job.

This gives automakers great leverage in the sourcing relationship, but it also begs the question: Why would suppliers put up with this? The answer is that there are benefits for both sides. While suppliers know they can be swapped out, they also know that if they keep the innovations and efficiencies coming, they’ll get long-term and even increasing work. A 70/30 split of work could become 60/40, but it could become 80/20, too. In addition, automakers provide financial and technical support to spur improvements—R&D costs are generally covered by the carmaker—so even if a supplier doesn’t win the assignment, the enhancements it made to its products and processes better position it to win work elsewhere. Bottom line: it’s now in the supplier’s best interest to advance the automaker’s best interest.

By contrast, IT sourcing rarely sees such an alignment of incentives. In many engagements, hands-off management and poorly written or ambiguous contracts give providers little reason to make improvements once the ink on the agreement dries. There is seldom someone waiting in the wings, and even when there is, lack of process documentation and know-how, as well as risk avoidance and bad experiences from previous switches, combine to keep companies from pulling the trigger. Or they pull it and misfire: without strong vendor-management capabilities, a company may find the next provider as disappointing as the first.

To shake things up—and get themselves closer to the automotive model—companies should think about moving to standardized environments that make switching providers a less Herculean undertaking. For some tasks, cloud-based services may prove a good option as they become more standardized (keep in mind, though, that even cloud vendors work on “stickiness” to keep customers from going elsewhere). Also worth considering is the “champion/challenger” model, which is particularly popular in application development. By assigning one provider the bulk of the work and another a nontrivial fraction, companies can, in effect, hedge their bets. Alternatively, there have been cases where for key outsourced processes, one vendor was tasked with execution and another with quality assurance—ensuring that the work was done well. Finally, should companies indeed switch vendors, they’ll find their odds of success improved by having their documentation in order and developing their own expertise, as described above.

Emphasize Transparency

The fourth way automakers improve sourcing is by constantly staying on top of vendor costs and performance. Manufacturers like Renault and BMW, for example, typically have significant staff—dozens if not hundreds of employees—dedicated to the single task of calculating the cost base of their suppliers. Carmakers often require suppliers to provide cost-related metrics, and they employ audits to verify the information. From an outsider’s perspective, this might seem a bit excessive—and perhaps even obsessive—but by understanding the costs of everything from raw materials to labor to depreciation, manufacturers gain insight into what they should be paying for components and where problems may be lurking.

Transparency on performance, meanwhile, is often enhanced by close working relationships with suppliers. Toyota, for example, sends engineers to key partners’ locations for periods ranging from days to months. The idea is not just to check—and, when necessary, improve—processes but to develop a freer flow of data and ideas between supplier and automaker. At the same time, procurement staff at Toyota closely work with vendors to better understand how they perform. This collaborative approach helps give the automaker a more accurate picture of how its sourcing engagements are going—and when it may need to take preventive or remedial action.

IT organizations, on the other hand, typically have nothing close to this level of transparency. They tend to pay for services based on a volume-centric measure—be it MIPS, terabytes, or number of transactions—that doesn’t shed light on the vendor’s cost structure. Without an understanding of that structure—the costs of the personnel, hardware, and other elements that make up the service—companies are hard pressed to negotiate an optimal price or to gauge performance.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Like carmakers, IT organizations can devote procurement staff to calculating the cost base of their providers and foster more dialogue and information sharing. Meanwhile, as companies develop more internal expertise, they’ll be better able to evaluate both the pricing and quality—and, in the end, the value—of the services they’re sourcing. They’ll also be able to identify how their own requirements drive up costs for both their vendors and themselves and make adjustments to avoid that tendency.

Striking a Better Balance

One of the main reasons IT-sourcing engagements disappoint—or fail outright—is that the relationship between customer and provider is off balance. Many companies have lost their expertise, have taken—or gradually veered toward—a hands-off policy for key processes, and have little ability to challenge or encourage vendors to deliver better performance and prices.

That balance can be restored. By embracing the lessons from the automotive industry and treating IT as a core part of their business, companies can get back in the driver’s seat in their IT-sourcing relationships—and enjoy a smoother road ahead.