Imagine a world in which electricity reaches even the most remote rural families in developing countries—those living far from today’s existing grid system—and provides them a means of working and studying late into the evenings. Imagine further that this electricity is green energy—solar home systems or biogas plants, for example. And imagine it were sold to the customers—most of whom live on less than $2 a day—for a price that makes the business financially sustainable and keeps it from depending on ongoing aid payments.

Impossible, you might say. And then you might travel to Bangladesh and come across Grameen Shakti, a social business that is thriving on just such a business model.

Many of the world’s most pressing social problems are so ingrained and widespread that they cannot be addressed solely by governments and traditional social sector organizations. Solving these problems requires a variety of approaches from the private and public sectors alike.

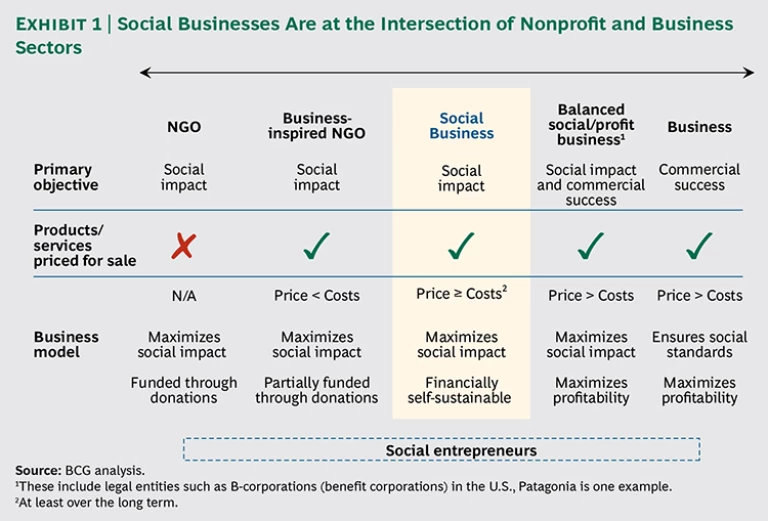

To this end, a wide range of new models is emerging along a spectrum that spans from nonprofits supported entirely by donations at one end to purely profit-oriented businesses at the other. By combining business principles with social objectives, these emerging models bridge the social and private sectors. Their various approaches can be distinguished both by the relative emphasis they place on social objectives versus profit objectives and by the degree to which they seek to generate their own revenues.

On this spectrum, social businesses—companies with a primary objective of solving a social problem by applying business principles—fall somewhere between traditional NGOs and for-profit companies. (See Exhibit 1.) Like NGOs, their primary objective is to create social impact. At the same time, they operate like businesses and aim to generate sufficient revenues to at least cover their operating costs.

Other emerging models, which lean further to the business side, try to weigh profit and social objectives equally; for instance, by aiming to generate at least a minimum profit while also pursuing a social impact goal. More toward the nonprofit side, business-inspired NGOs aim to generate at least some additional revenue by pricing their services, yet without the ambition to reach financial sustainability.

The Basics of Social Business

Although all these emerging models vary in the degree to which they combine profit targets with social targets, they all are built around the same basic belief: applying business principles to social problems can significantly increase efficiency, effectiveness, and financial sustainability. That’s why many of the lessons from social businesses can also be applied to other emerging business models.

Exact definitions of “social business”

Because social businesses don’t have as a goal increasing shareholder value or paying dividends, they are free to focus on the neediest, most underserved segments of the world’s populations—segments that traditionally fall outside the focus of profit-driven businesses. And because they price their products and services in a way that generates enough revenue to be self-sustaining in the long-term, these organizations do not depend on donations or other forms of external financial support to deliver their mission. Ultimately, social businesses maximize value delivered to society as opposed to the financial value delivered to shareholders.

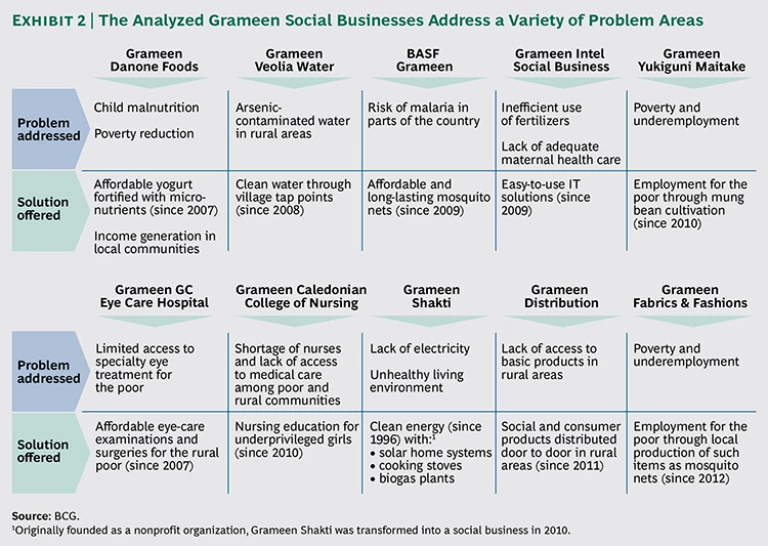

Today, social businesses exist in developing and developed countries alike. Many of the social businesses BCG analyzed for the November 2013 report The Power of Social Business: Lessons from Corporate Engagements with Grameen, are joint ventures between a Grameen organization and a multinational partner such as Danone, Intel, Veolia, and BASF. (See Exhibit 2.)

Although many are still in the early phases of development, some—like Grameen Shakti, which has revenues of about €72 million and more than 12,000 employees—demonstrate the potential scale of these ventures. Most important, however, are the social and business benefits that these organizations deliver. (See Exhibit 3.)

Social Benefits

With their focus on social impact and self-sustainability, social businesses can theoretically provide solutions to almost any social problem. As demonstrated by the range of social businesses BCG analyzed, such problems include fighting hunger and malnutrition, increasing the agricultural productivity of rural populations, offering poor rural households access to an environmentally friendly electricity supply, providing employment opportunities in areas where jobs are limited, and improving the health and life expectancy of local populations.

One example is Grameen GC Eye Care Hospital, which was founded in 2007 to tackle the prevalence of blindness and eye conditions such as farsightedness among the poorest populations in Bangladesh. The hospital provides low-cost eye care—including eye exams and cataract surgery—at three locations, and it extends its reach into the poorest, most rural areas through its traveling “eye camps.” By charging patients for its services based on their ability to pay, the hospital is affordable.

Although 20 percent of its 545,000 patients receive services at a very reduced price, the hospital still manages to break even due to its efficient operations and the income from higher-margin patients. To date, an estimated 2,500 blind patients have regained their eyesight as a result of the hospital’s services. In addition, the business has created 237 local jobs. Now that the model has proven its viability, efforts are underway to scale it up further, and two other eye-care hospitals are under construction.

Similarly, the other social businesses analyzed create tangible social impact—the degree and extent of which depends on the business stage they are operating in. Grameen Danone Foods, for example, reaches more than 300,000 customers with fortified yogurt, and preliminary scientific studies point to the impact that the yogurt has on children’s growth rates and ability to concentrate.

BASF Grameen’s insecticide-treated mosquito nets (which are sourced from Grameen Fabrics & Fashions, another social business) protect more than 75,000 families from insect-borne diseases. Grameen Shakti’s solar home systems provide more than 1.2 million families with access to clean electricity, and Shakti’s improved cooking stoves create a cleaner living environment for roughly 700,000 households. Grameen Yukiguni Maitake has created 8,000 jobs in the cultivation of mung beans, providing new employment opportunities for farmers in rural Bangladesh. Furthermore, it recruited new employees as field supervisors and built a sorting factory.

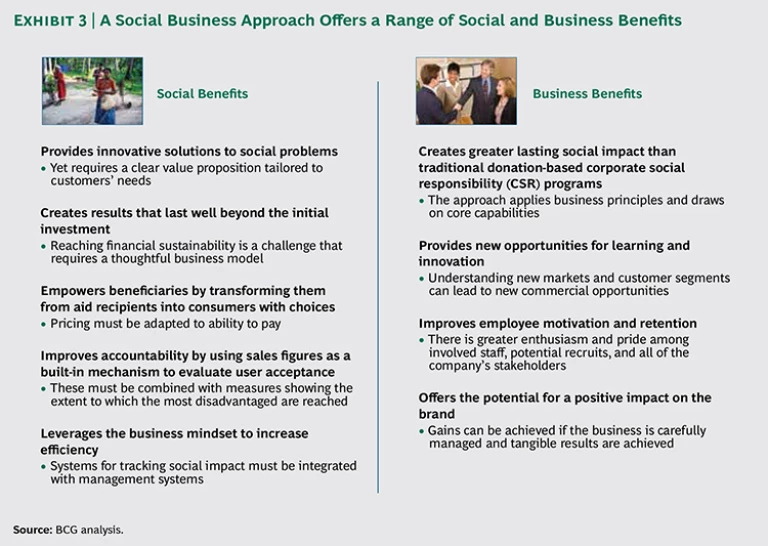

These solutions are designed to provide long-lasting, self-perpetuating benefits. Unlike traditional charitable organizations, which spend donated funds every year, a successful social business has self-sustainable operations because it is set up to recoup every dollar it invests. Social businesses also empower populations in need, transforming them from beneficiaries of charitable aid to independent consumers who have a choice and a stake in their own futures. In addition, by tracking sales figures and working with a business mindset, social businesses can achieve greater accountability and efficiency—further increasing the social return of every dollar invested.

Business Benefits

Unlike traditional, donation-based corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, social businesses allow companies to directly use their skills, expertise, and business network to address a particular social problem. In this way, social business activities can be aligned with the core commercial business. If designed and managed effectively, this alignment not only generates lasting social impact but also can lead to tangible business benefits.

According to the corporations we surveyed, the most important business benefit that social businesses can provide is the potential for learning and innovation. All along the value chain, companies often find that the new products, operating models, marketing strategies, and distribution approaches aimed at reaching those most in need have a broader commercial application and can be a source of competitive advantage for the core business. For instance, Grameen Danone Foods set a goal of improving the health of children in Bangladesh by selling nutritious, affordable yogurt to local families. To maximize efficiency and create local employment opportunities, Grameen Danone Foods built the smallest plant that was technically possible—its capacity is below 4 percent of the typical capacity at a Danone factory in Europe. This production approach sharply reduces capital expenses and provides an innovative blueprint for small-scale production that Danone can leverage in other emerging markets. (For more details, see the sidebar “An Interview with Jochen Ebert on Grameen Danone Foods.”)

An Interview with Jochen Ebert on Grameen Danone Foods

Jochen Ebert is the managing director of Danone India. Previously, he managed the launch of Grameen Danone Foods in Bangla-desh, a social business that sells fortified yogurt at affordable prices. The yogurt is specifically formulated to address child malnutrition among the poor in rural parts of the country. BCG spoke with him about the business benefits that a social business can deliver.

What impact did Grameen Danone Foods in Bangladesh have on Danone’s core business?

Grameen Danone Foods allowed us to experiment with new approaches and processes. A big corporation becomes more and more top-down in the way it is managed. Our social business in Bangladesh was really created bottom-up. Instead of being part of a big hierarchy, we were a small group of people making decisions. This had a significant impact on how we ran the business.

For example, it was absolutely unthinkable for Danone to have a factory that generated fewer than 20,000 tons of yogurt per year. Yet our factory in Bangladesh has only a 2,000-ton capacity and far lower capital expenses. Here, we are capable of managing small, and we try to keep costs as low as we can. Since this is a small start-up and we cannot afford high overhead, we’ve had to put very junior people into senior management positions. We have had time to experiment, because the absolute losses that we create are not so significant. This is revolutionary thinking for a company like Danone.

Also, there have been fantastic new learnings in terms of going to market, understanding and reaching consumers, and creating products that our customers want. The direct-delivery systems we created in Bangladesh are smaller and more effective than what we have in many other countries. And we’ll be launching some products in France that were strongly inspired by our products in Bangladesh.

Our social business is a lever that people still don’t fully understand because the traditional communication and learning flows are from West to East. People in the West aren’t very open to hearing, “Here’s how we do it in Bangladesh.” But it’s an extremely powerful tool, especially if more and more people in the company have these kinds of experiences. We underexploit it massively, but we’ve learned a lot from it.

You mentioned that Danone will be launching some products in France that were inspired by the Bangladesh experience. Can you tell us more?

We made some innovations in the product formulation. Milk is very expensive in Bangladesh, but other ingredients can provide the needed nutrition profile at a lower cost. These ideas can be applied in developed countries as well.

Another idea with the potential to travel elsewhere is how we go to market—and the need to explore different distribution channels. In developed countries, such as Germany and France, we sell 80 percent of our products through supermarkets. But in India, for example, we sell via carts. I don’t know if this approach is completely applicable in other areas, but the very act of breaking down mental barriers can be hugely inspirational for big companies.

In Europe, where there are many steps between the manufacturer and the consumer, there may be opportunities to sell products directly—and not necessarily via carts going through Paris. We have a big Danone building in Spain where we sell products directly to consumers. It wasn’t directly inspired by Bangladesh, but this type of thinking can lead to innovation.

Have you gained any other insights from your Bangladesh experience?

One key learning is in the area of business planning. Companies are spending an increasing amount of time planning and then translating those plans into PowerPoint charts. In Bangladesh and India, we learned that it doesn’t really help to plan more and more and more—your plan is going to be wrong.

This experience radically changed how I look at the process. I no longer see it as first the planning, then the action. Now it’s first the action, then the planning. It’s really the ability to act something out, to experiment with something that may be a little vague or entrepreneurial. Since we can’t manage uncertainty, it’s better to manage small, modular experiments and see their impact on the business—instead of taking the traditional approach of adding one business plan to the next, knowing that they’ll never happen but pretending they will.

To generalize, if a company wants to take the risk of building businesses in emerging countries, then it also has to take the risk of nonplanning, taking action, and then planning. If it doesn’t work, you cut your losses and exit. And if it works, you adjust it step by step. This is a permanent, interactive process of correction. It is very, very unlikely that you’ll get it right the first time. I have never seen that, because these countries are fundamentally different than where you’re used to operating.

When companies enter a new region, social businesses can also provide valuable insights into the legal, regulatory, and political environments. BASF Grameen’s primary social objective is to protect populations against insect-borne diseases, but the business also provides an opportunity to learn more about the Bangladeshi market and consumers—lessons that may eventually help BASF explore new business opportunities.

Social businesses can also provide less tangible but equally important employee benefits. Giving employees an opportunity to become involved in a social business can give them a sense of purpose and new personal- and professional-development opportunities. By providing experiences that enrich the lives of their employees, companies can strengthen employee engagement, job satisfaction, and retention. These types of experiences are especially valued by today’s “Millennial” generation (those born between 1980 and 2000). For members of this generation, experiencing a sense of purpose is an integral part of their lives and plays an integral role in their career choices. (For more information about the survey, see The Millennial Consumer: Debunking Stereotypes, BCG Focus, April 2012.)

Finally, achieving true social impact can also enhance a company’s reputation and brand by helping to build a network and goodwill with important stakeholders. Public campaigns to encourage corporate recognition of social issues demonstrate the growing power that external stakeholders can have on business success. Building long-term relationships across all of society—including public decision makers, opinion leaders, and influencers—through an integrated stakeholder-management approach is critical for building support for a company’s interests and operations.