The past decade has seen substantial evolution in the aerospace and defense landscape. There have been wars followed by troop drawdowns, budget sequestration in the U.S., a boom in commercial aviation, and ongoing changes in the industry’s structure. As management teams look toward the next decade and beyond, they are asking fundamental questions about portfolios and cash deployment, including the following:

- Should we return cash to shareholders or invest in growth?

- Would balanced exposure to both defense and commercial segments create more value during the aerospace and defense business cycle?

- Would reducing the asset base lead to greater returns and value?

- Are suppliers creating more value from their positions on platforms than prime OEMs?

Answering these questions requires separating the sector’s conventional value-creation wisdom from myths that have gained currency during the past several decades. To separate myth from fact—and empirically answer these questions for management teams—we analyzed the financial performance of 51 publicly traded

Putting Conventional Wisdom to the Test

Many analysts, shareholders, and even industry insiders subscribe to a set of beliefs about the aerospace and defense industry that have become virtual articles of faith. The TSR data that The Boston Consulting Group has compiled and analyzed offers the opportunity to test those beliefs against empirical data. In doing so, we have been able to demonstrate that some beliefs are grounded in fact, but others are myths that hinder understanding of the sector and its sources of value creation. We review these beliefs and offer our verdict on their accuracy.

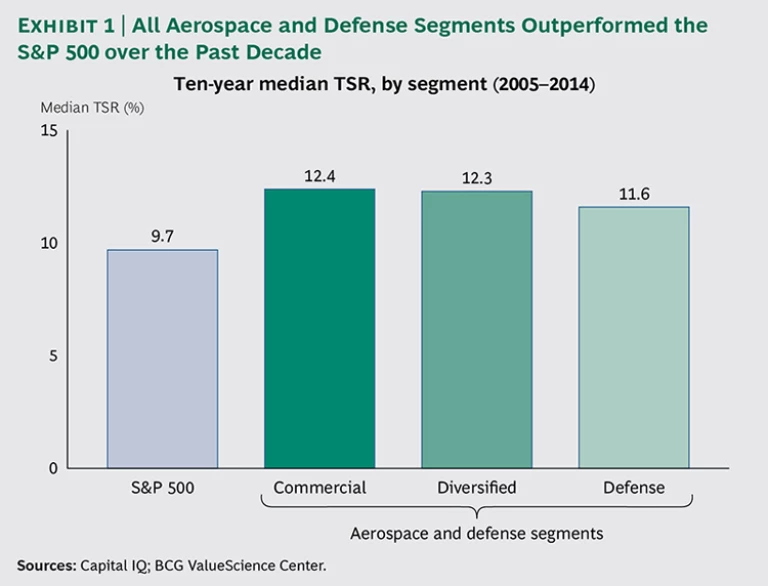

Aerospace and defense companies have outperformed the broader market over the short, medium, and long term. Fact. Companies in the sector have created more value than the overall market throughout the aerospace and defense business cycle. In the ten-year period from 2005 through 2014, the aerospace and defense sector generated 12.1 percent in annual TSR, compared with 9.7 percent by the S&P 500.

This trend of strong sector performance holds across three-year and five-year periods, as well as across the defense, commercial, and diversified segments of aerospace and defense companies over all the time periods we studied. (In addition, although BCG’s TSR data extends only as far back as 2004, our analysis of other metrics shows that, in terms of value creation, the industry has been performing better than the overall market for more than 20 years.) In terms of segments, companies focused on commercial segments created slightly more shareholder value than defense-focused peers—12.4 percent annualized versus 11.6 percent—over the past ten years. (See Exhibit 1.)

The myth that value creation in aerospace and defense companies cannot keep pace with the overall equity market is especially prevalent in Europe. This is because of a misperception that the defense market is depressed and companies in the sector are subject to extensive government oversight that influences corporate governance. Although barriers do exist—in Europe and elsewhere—companies on average have sustained a high level of value creation across all regions.

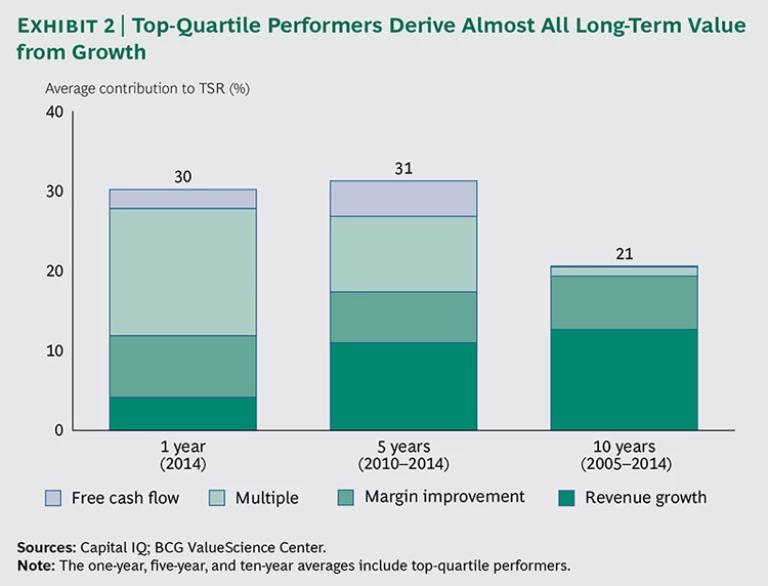

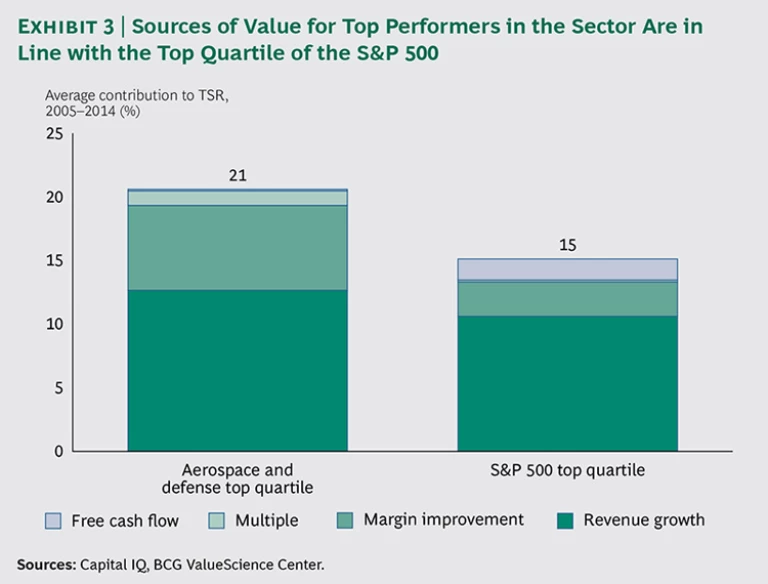

In the long run, growth is the most important source of value creation for aerospace and defense companies. Fact. For the period we analyzed, revenue growth was the source of more than half of the sector’s long-term value creation, as it was for companies in the S&P 500. In terms of contribution to value creation over the long term, growth trumps margin improvement, valuation multiple, and cash returns to shareholders.

Notably, revenue growth has driven nearly two-thirds of the TSR of top-quartile performers in aerospace and defense over the past ten years, while margin improvement has driven much of the remainder. Capital deployment, dividends, and share repurchases have been only small contributors. (See Exhibits 2 and 3.) By contrast, during the same period, median-performing companies derived about 15 percent of their value creation from financial policy and saw no contribution from multiple expansion.

The takeaway is clear: over the long term, revenue growth—followed by margin expansion—is the key driver of value creation. Yet growth can destroy value if it comes at too high a price. Among the companies we analyzed are a few that have grown during the cycle but nonetheless posted TSR numbers that trail the median. These “growing value destroyers” tell a cautionary tale: low-value growth carries a high risk of amplifying investor concerns regarding strategy.

The primacy of growth as the long-term value-creation driver has major implications, particularly for companies in the increasingly challenging defense market. In the current environment, companies must find and capture growth in both their core businesses and adjacent markets. However, many in the defense segment are pursuing similar strategies, such as international growth, or are focusing on a few adjacent commercial spaces. Competition in these pockets of growth is intense, and growth will be difficult.

In the short term, multiple expansion is an important source of value creation. In the past five years, multiples have risen, indicating high expectations from investors. To meet these expectations and maintain their current valuation multiples, companies will need a clear strategy and strong communication with institutional investors over the next three to five years. BCG’s smart-multiple methodology empirically identifies the drivers of valuation multiples—that is, how investors view the future prospects of companies in the sector. This methodology explains roughly 80 percent of the variation in multiples for a given segment, and it provides critical insights for companies seeking to improve their value-creation performance.

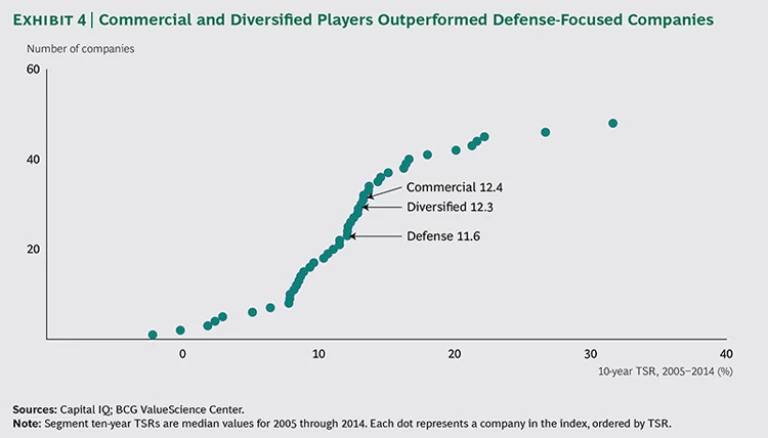

Players with substantial exposure to both the defense and commercial-customer segments perform better than single-focus players over the long run. Myth. Over the cycle, a company’s target end user (commercial aerospace or defense) has not been a major determinant of value creation. The differences are small: companies with mostly commercial-customer exposure performed slightly better than diversified players over the past decade. During that period, pure defense players trailed by less than 1 percentage point of TSR per year. (See Exhibit 4.)

Customer focus made a much bigger difference in the value creation performance of tier two suppliers. Diversified tier-two suppliers posted a median annual ten-year TSR of 13 percent, well behind the 18 percent that commercially focused tier-two suppliers generated over the same period. (Our sample contains no tier-two suppliers focused exclusively on defense customers.)

Suppliers further up the value chain have higher margins than prime OEMs. Fact. Tier two players, which supply components and subsystems to tier one players and prime OEMs, have margins on earnings before interest and taxes that are 10 percentage points higher than prime OEM margins, and 7 points higher than those of tier one suppliers. Factors that contributed to this disparity over the past decade include intellectual property related to design and manufacture, risk-sharing partnerships, access to aftermarket profits, long-term contracts, and the ability to serve multiple programs and regions.

There is some indication that the pendulum is starting to swing: the margins of tier two suppliers contracted in 2014. Prime OEMs and tier one suppliers are increasingly competing on affordability. With an average two-thirds of a platform’s cost structure consisting of supplied materials, cost pressure will shift to tier two suppliers through improved negotiating, dual sourcing, insourcing, and restructuring aftermarket arrangements. These dynamics have the potential to significantly shift the distribution of profit pools within the value chain.

Of the industry’s subsegments, prime OEMs are the superior value creators over the long run. Myth. The value creation performance of aerospace and defense companies varied widely during the past ten years, but of the 13 companies in the top quartile of value creation, only two were prime OEMs. Prime OEMs were the weakest value creators, generating a median TSR of 8 percent from 2005 through 2014, compared with 12 percent for tier one suppliers and 13 percent for tier two suppliers. A pattern has emerged over the past decade: the further a company is from the end customer, the greater that company’s ability to create value for shareholders.

A drive by prime OEMs to reduce assets and become “asset light” has rendered them less asset intensive than tier one and tier two suppliers. Myth. Prime OEMs have lowered the level of their asset holdings, largely through a series of high-profile spin-offs and other asset-reduction efforts.

However, prime OEMs are still not asset-light companies in absolute terms or in comparison with tier one and tier two suppliers. The median asset intensity (the amount of gross fixed assets required to generate a dollar of revenue) for all three value-chain segments is quite similar, although prime OEMs are slightly more asset heavy than their tier-one and tier-two counterparts.

Prime OEMs may have shed assets, but the process of developing and integrating platforms with an increasingly complex supply chain is costly and requires significant assets. As these companies continue to demand better cost and quality performance from suppliers, they must determine the right level of assets, especially in cases in which supplier systems or components are brought back in-house for strategic reasons. (See “ Value Chain Reintegration: Undoing Asset-Light Business Models ,” BCG article, December 2014.)

Asset-light aerospace and defense companies generate the highest returns. Myth. Generally speaking, companies with lower asset intensity tend to generate higher return on capital employed (ROCE). However, companies that consistently deliver the highest ROCE are moderate- to high-asset-intensity businesses. A low asset base is not a necessary condition for generating high returns. At the extreme, operating models with a very low asset base imply lower barriers to entry and invite competition, while a larger—and well-managed—asset base can be a competitive moat. (See Exhibit 5.)

Questions for Senior Aerospace and Defense Leaders

It has been a good decade for the sector in terms of value creation. Yet new industry dynamics and risks are emerging that will have implications for value creation in the next ten years and beyond. The challenges include continued uncertainty for defense budgets and low defense-sector growth, questions about the sustainability of commercial order books, cost pressures on suppliers, new technologies, affordability issues for new commercial and defense platforms, and efforts to simplify the supply chain.

In the midst of these uncertainties, understanding the industry’s value-creation performance can help management teams make smarter decisions regarding their portfolio, end-market exposure, cash deployment, and other parameters for the next ten years. However, they must address the right set of factors by asking themselves some tough questions:

- How has the company performed relative to others positioned similarly in the market? What are the opportunities for pulling away from the pack?

- How should we structure the portfolio relative to end markets and value chain positions to generate superlative value creation?

- How much growth do we need? And do we have the portfolio and market position to drive that growth?

- What is the optimum balance between returning cash to shareholders and investing in growth?

- Do we have the right asset strategy (for example, insourcing versus outsourcing)? How would a change in our asset structure affect value creation?

A methodological approach to strategy—factoring in the competitive landscape, financial implications, and the requirements of investors—can help management teams determine the right answers to these questions. The resulting roadmap can include new acquisition targets, divestitures, updated R&D agendas, cost reduction imperatives, new supplier arrangements, and new talent and people capabilities. Many of our clients are already pursuing these options. Regardless of the approach they choose, company leaders must rely less on intuition and more on objective facts—informed by an understanding of value creation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Bailey Hand and Philippe Dehillotte. They would also like to thank Harris Collingwood and Jeff Garigliano for their help in writing this report, as well as Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Elyse Friedman, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, Anna Hoang, and Sara Strassenreiter for their contributions to its design, editing, production, and distribution.