Success in the past always becomes enshrined in the present by the over-valuation of the policies and attitudes which accompanied that success.

—Bruce Henderson

Commoditization is often seen as the kiss of death for an industry. Boding ominously for profit margins, it brings slowing growth, falling prices, and increasing competition. In recent years, the process of commoditization has accelerated. Company life cycles have halved in the past 20 years: markets mature faster and incumbents are more and more at risk of commoditization. (See “ BCG Classics Revisited: The Growth Share Matrix ,” BCG article, June 2014; and “ Adaptability: The New Competitive Advantage ,” BCG article, August 2011.)

But does commoditization have to be bad for every company? While many fail to navigate this commoditization process effectively, others are able exploit it and flourish. Take the case of Wal-Mart, which faces rapid commoditization in the retail industry. By adopting a low-cost approach through scale and efficiency, the retailer was able to achieve a five-year (2009 through 2013) total shareholder return of nearly 10 percent even as many other big-box retailers were being forced into bankruptcy. Or consider Apple’s success in the highly commoditized PC industry. Utilizing a well-tuned differentiation strategy focused on design and user experience, Apple captured 28 percent of global PC profitability with market share of only 6 percent in 2014.

What enables companies such as Wal-Mart and Apple to flourish under conditions of commoditization while others stagnate or perish? As these examples suggest, there is more than one approach to escaping the doghouse of commoditization. Success lies in choosing the right one to suit your particular situation. The first step toward this determination is to understand when and how commoditization is happening.

Drivers and Signals of Commoditization

Commoditization occurs when the market perceives products to be substitutable. Two common factors drive this substitutability. The first is the emergence of a standard design or technology in the marketplace. Initially, multiple technologies compete to become the market standard. As the market matures, companies converge on one standard, bringing greater parity across offerings. For example, when Gillette introduced its multiblade Mach3 system into the men’s shaving market, its offering was clearly differentiated from single-blade competitors. However, competitors adapted to the new multiblade standard: Gillette’s sales growth flattened, and prices were squeezed to maintain market share.

The second is an increase in pricing and product feature transparency. When customers can more easily compare products, they are more willing to switch from one to another. Similarly, when companies can see competitors’ offerings in real time, they are quicker to adapt to innovations by others, thereby shortening the life span of any move toward differentiation or cost advantage. This was the case with the airline and auto insurance markets in the early years of this century, when online marketplaces allowed greater transparency and increased commoditization pressures. As perceptions of substitutability grow owing to one or both of these drivers, commoditization is accompanied by the following set of common warning signs:

- Increasing Price Sensitivity. As switching costs drop, consumers better understand product qualities and place a greater focus on price, acquiring higher negotiating power.

- Increasing Price Competition. Companies begin to cut prices to attract customers. This creates a downward spiral on prices throughout the market, squeezing margins across the board.

- Industry Consolidation. As companies struggle to survive, larger companies acquire smaller companies to gain advantages in scale, reach, and capability.

Taken together, these changes shift the way value is distributed in an industry. As prices decrease, the overall profit pool shrinks. At the same time, there is a shift in how value is spread among producers, distributors, and consumers. The share of value captured by existing modes of differentiation diminishes. Value instead shifts to companies that offer the lowest-cost production, the best monetization of market inefficiencies, or both.

To flourish under these changing conditions, companies need to navigate a number of critical strategic choices guided by a clear view of how value is shifting in their industry.

Navigating Commoditization

Amidst the shifting tides of a commoditizing market, many companies find themselves unsure of how best to steer the ship. Should we economize and ride out the storm? Change our position in the value chain? Or, perhaps, exit and realign the portfolio with growing markets? While each move might offer some benefits, finding the best one requires that companies assess the changing nature of advantage and adapt their strategy and business model accordingly. To navigate the troubled waters of commoditization, managers should take two steps. First, understand and predict the evolution of value pools in the market. To develop this understanding, companies should analyze the current state of the market and predict its future state along two dimensions:

- An assessment of the structural advantage reveals the potential for sustainable price or cost advantage in the market. It measures the extent to which companies can extract value through classical static sources of advantage such as differentiation and cost.

- The dynamic advantage is the measure of the ease and transparency with which market supply can meet demand. Market imperfections—such as inherent market-price volatility and structural asymmetries of information between buyers and sellers—increase the potential for dynamic advantage. These imperfections create arbitrage opportunities, which can be exploited to extract value from the market.

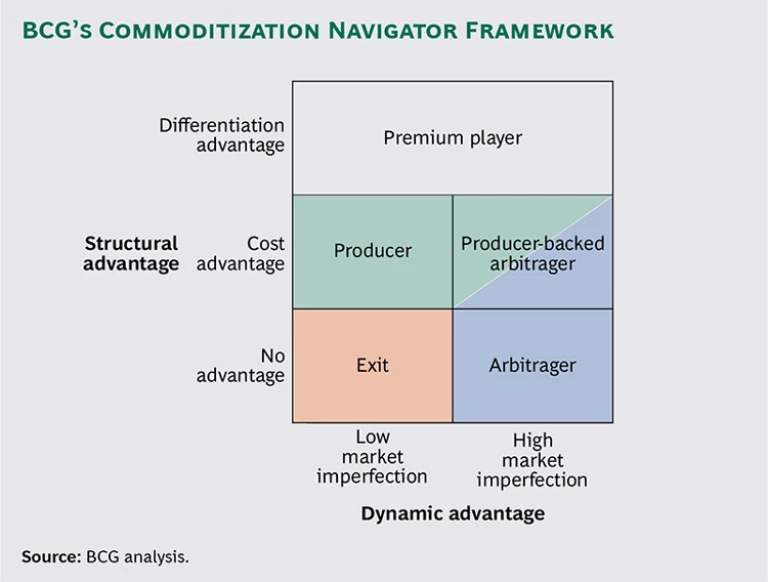

Translated into a matrix—The Boston Consulting Group’s commoditization navigator framework—these two dimensions define five market environments. (See the exhibit below.) Each of the five market environments implies distinct optimal strategies and operating models for extracting value from a market:

- Premium Player. This is the optimal strategy for a market in which the dominant source of advantage is through meaningful differentiation, which diminishes direct competition. Leading companies are able to command a price premium in the marketplace on the basis of their innovation, brand, patent protection, and market access. In the case of a commoditizing market, this amounts to enhancing or protecting existing sources of differentiation or creating new ones. Examples include specialty pharmaceuticals and luxury goods.

- Producer. This is the optimal strategy for a market in which cost is the primary driver of advantage and market imperfections are low. Market leaders win on the basis of more efficient cost structures that arise as a result of scale and experience, product design, supply relationships, or process innovations. Examples include oil production and the mining industries.

- Arbitrager. This is the optimal strategy for a market in which exploiting imperfections is the primary source of advantage. As companies cannot establish stable price premiums or cost advantage, value aggregates with those that can identify and exploit temporary mismatches in supply and demand. Examples include fixed-income and foreign-exchange trading.

- Producer-Backed Arbitrager. This is the optimal strategy for a market in which both cost-based advantages and market imperfections are available. Leaders can deploy one or both sources of advantage to extract value from the marketplace. Examples include oil refining and trading and power generation in deregulated markets in which asset-backed strategies provide both direct (cost) and indirect (informational) advantage.

- Exit. When neither structural nor dynamic advantage is available, the best strategy is to exit and redeploy resources to more attractive markets.

The most common mistake companies make when they face commoditization is failing to recognize and adapt to changes in market conditions. Legacy business models are no longer a basis for succeeding when a market commoditizes. Too often, incumbents persist with incremental innovation, which proved successful under market conditions suited to a premium-player model but will not work once price premiums are no longer supported in the market. Instead, winning requires a clear prospective vision of shifting market dynamics as a basis for driving internal change.

The second step for crafting an effective commoditization strategy is to identify the viable moves for your company. As the structure of value evolves in the market, so too should your strategy and business model. To accomplish this, you should combine your diagnosis of the future evolution of the market with an objective view of your current cost position and existing capabilities vis-à-vis the competition. Companies with a differentiation strategy need to assess whether the market will support another wave of differentiation or whether there will be a shift that, for example, will make the producer model the optimal strategy. Low-cost companies need to assess whether cost advantage will continue to be possible. Both need to assess whether market imperfections present an opportunity for extracting value through arbitrage models. Whatever the case, moves that align existing or potential capabilities with market dynamics will provide the best foundation for flourishing in a commoditizing market.

It is important to note that if your market analysis suggests that there is limited opportunity for either structural or dynamic advantage, your best move may be to exit the market altogether. This is what IBM did in the PC market. After driving innovation in the PC market with its open-architecture 5150, IBM became the market standard from the 1980s through the early 1990s. However, by the mid-1990s, lower-cost manufacturers overtook IBM’s lead, flattening the cost curve. The market had moved to favor a producer model, making it hard for IBM to compete. Recognizing its inability to compete effectively on cost or differentiation and the lack of market imperfections it could easily exploit, in 2005, IBM sold its PC business to Lenovo, a Chinese computer-technology company. This strategic portfolio adjustment allowed IBM to focus its attention on its fast-growing and profitable service and software businesses.

To prepare for the transition to a new strategy, it is critical that you define the capabilities necessary to succeed. Adjusting to the changing dynamics of the market often means retooling for new capabilities to capture value in a different manner. The innovation, experimentation, and customer insight needed to win as a premium player are very different from the optimization, efficiency, and scale capabilities that drive success for cost-leading producers. Taking advantage of market inefficiencies requires extreme agility, mastery of signals, and possession of strategic positions. Having a clear roadmap that shows how the organization will retool itself for the future is vital for staying a step ahead of the changing winds of commoditization.

Lessons from the Airline Industry

It is possible to see the potential for failure and success in the face of commoditization by applying the commoditization navigator framework to the U.S. airline industry. During the 1960s and 1970s, regulation controlled prices, routes, and even market entry of new competitors. This enabled a number of national and regional carriers to carve out differentiated models that were based on location and to maintain attractive margins.

The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 opened the door to new entrants and increased competition across the industry. As the industry commoditized, incumbents such as American Airlines and United Airlines were forced to compete with no-frills, low-cost carriers such as Southwest Airlines and Spirit Airlines. This increased price competition compressed margins for most companies.

The structure of advantage moved away from premium players and toward cost-advantaged producers, and the incumbent airlines were slow to adapt. In the beginning, they continued to stick with the premium-player model. Emulating the American Airlines AAdvantage program, which was started in 1981, each airline launched its own frequent-flyer program to increase switching costs for customers and introduce a new basis for advantage that focused on rewards, perks, and privileges. While these loyalty programs proved to be popular with customers, they were not sufficient to stave off commoditization pressures.

As differentiation strategies waned in their efficacy and financial pressures increased, larger airlines began to adopt a more producer-centric mind-set, striving to achieve a cost advantage versus competitors. They added seats, reduced service, and unbundled their service offerings—such as free meals and baggage handling—in order to pass costs along to consumers. Larger players such as American and United were able to leverage their scale to realize greater efficiencies. However, leading incumbents such as Pan American World Airways and Trans World Airlines perished when they failed to adapt their focus on differentiation to the shifting value pools of the industry.

In the early years of this century, the rise of online travel agencies such as Expedia and Travelocity increased the transparency of pricing imperfections in the marketplace. Passengers could now easily compare airline prices and choose the lowest-price option, further increasing commoditization pressures. Responding to these evolving market trends, industry leaders opted for a producer-backed arbitrager strategy that enabled them not only to extract value through their core service offering but also to address market imperfections in the pricing of tickets. Five leading airlines—United, Continental Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Northwest Airlines, and American—partnered to develop their own online-ticketing platform, Orbitz. Like its competitors, Orbitz allows the consumer to compare ticket prices across airlines and more easily find the best deal. On the one hand, this move facilitated price competition, but on the other, it made it possible for the airlines to capture the transaction fees associated with online ticket purchases and reduce distribution costs associated with processing ticket purchases through other platforms. In this sense, Orbitz enabled the airlines to add an additional layer of value creation by addressing, rather than ignoring, market imperfections related to the pricing of their own service.

Imperatives for Action

Commoditization can be just as much an opportunity as a risk for your business. Incumbents can unlock new value potential by adapting their strategy and operating model. However, change can be hard—especially when it requires modifying well-established formulas of success. To help managers embark on the path of commoditization, we recommend the following:

- Assess the current basis and project the future basis for advantage. Understand the evolving nature of advantage in your market. In particular, estimate what value a producer or an arbitrager would be able to extract. Although it can be difficult to predict with high certainty a path for market development, scenario planning offers a way to think through a range of plausible outcomes.

- Identify winning business models. Sources of advantage in your markets are continually evolving and can require capabilities that differ from those you have now. Identify the segment in the matrix for which you will need to be ready and develop a new vision for success there. Articulate a clear strategy and define the required business model to make it work.

- Consider resegmenting by business model. Rather than segmenting the business by product type or region, managers should consider the option of segmenting by market environment. Businesses that deploy a similar strategy, such as premium player or arbitrager, will share a similar set of capabilities and may benefit from cross-pollination.