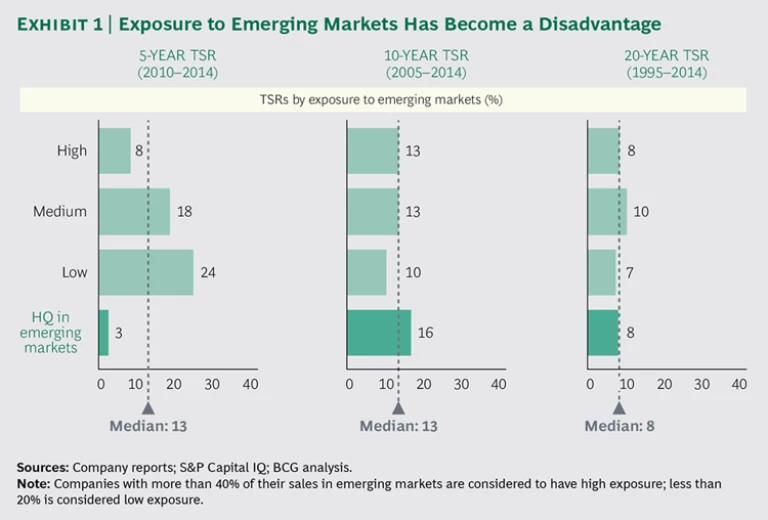

For publicly traded chemical companies, emerging markets are no longer an elixir. Chemical companies based in Asia Pacific and Latin America have had a rough ride over the past few years in terms of stock market returns, and even North American and European chemical companies that do a lot of business there have paid a price. The economic slowdown in emerging markets, overcapacity, and a profusion of me-too strategies have made it harder for chemical companies to stand out from the pack and turn a profit.

The challenges are evident in The Boston Consulting Group’s latest analysis of the chemical industry’s five-year

But the TSR results are not a reason to reduce activity in emerging markets. Rather, chemical companies should look to fine-tune their tactics and strategies so that they will be positioned to take advantage of the growth that will inevitably re-emerge.

At the moment, China is the emerging market posing the most challenges to chemical companies. There are simply too many chemical companies in China chasing too few customers. In addition, Western companies have exacerbated their problems there by focusing largely on commodity chemicals and by following what once was considered a surefire route to success: steering capital toward plants and proprietary technology.

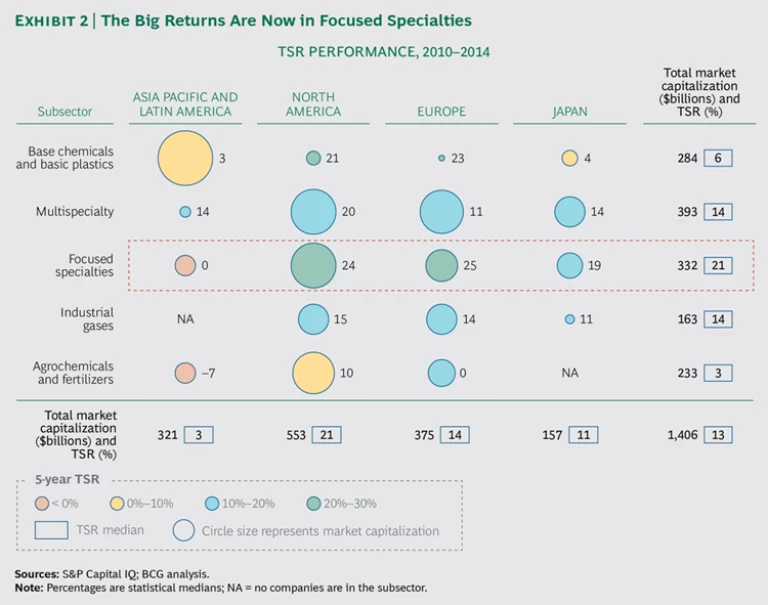

Focused Specialties’ Advantage. In all markets, the industry’s biggest TSR returns have shifted from commodity products manufactured in extremely high-capacity plants to focused specialties. Focused specialty companies create highly refined products that usually serve a narrowly defined industry or functional application—including coatings, adhesives, flavors and fragrances, construction, and electronics materials. In the latest five-year period, focused specialties had a median TSR of 21%, the highest of the five chemical subsectors. (See Exhibit 2.)

Many of the focused specialty companies that have done the best have highly differentiated business models. For instance, the UK company Croda International has earned excellent annual returns (30% in the latest five-year period) by focusing on high-performance specialty additives and selling directly to customers instead of using distributors. Proximity to customers is also behind the success of Balchem. The US company rotates staff infrequently, knowing that its food-industry customers need to be able to trust what Balchem's managers tell them about the ingredients the company provides. Partly as a result of its close relationships with customers, Balchem has been able to maintain an average EBITDA margin of 22% for the past 17 years and has a 20-year TSR of 25%—the best long-term TSR in the industry.

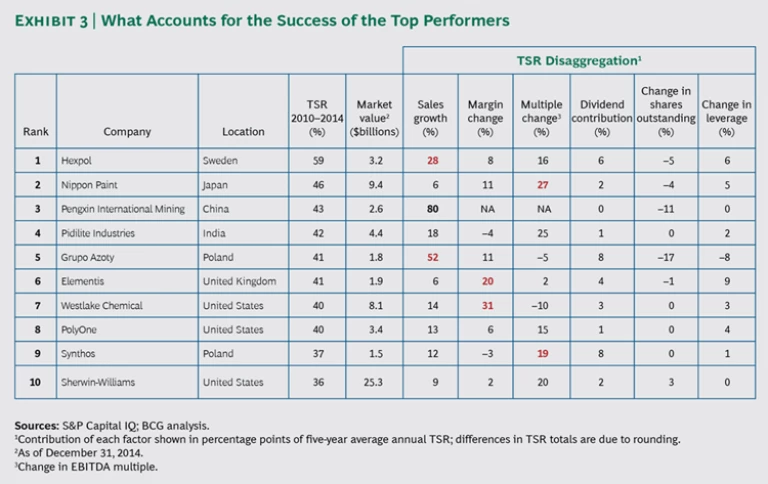

Indeed, away from the influence of emerging markets, many parts of the industry and many individual chemical companies are thriving. The median TSR of the ten top-performing chemical companies is 41%, sixth among the 27 industries BCG analyzed. (The 13% median TSR of all 145 companies included in the study puts the industry as a whole in 20th place.)

For the most part, the chemical industry’s top performers fit the pattern of differentiating themselves through something other than proprietary manufacturing technology.

For example, Sweden-based Hexpol, which has a five-year TSR of 59%—the best in the industry—has set itself apart by developing custom-grade compounds, including in flame-retardant rubber. The company’s strategy is more dependent on capabilities than on capital investments. The number two performer, Japan’s Nippon Paint (five-year TSR: 46%), has succeeded by training local craftsmen in the markets where it operates—a model that would be difficult to copy. Pidilite Industries (five-year TSR: 42%), one of two emerging-market companies in the list of top-ten performers, has become one of the most successful adhesives manufacturers in India through a superior understanding of local needs and an astute use of Indian media channels. Elementis, in the UK (five-year TSR: 41%), has distinguished itself with a range of high-quality functional additives and customized formulas that are crucial to the performance of coatings and other chemical systems. And finally, the US paint company Sherwin-Williams (five-year TSR: 36%) has more than 3,700 paint stores in the United States alone—a high-service commercial network that would be almost impossible to replicate.

Their unique positions have allowed these companies (all but one of them in the focused specialties subsector) to shield themselves from competition in a way that companies more dependent on scale or proprietary manufacturing technology cannot. That has helped them grow faster or earn higher profits than others in the market—attributes that have contributed to their TSRs. (See Exhibit 3.) In their differentiated product offerings and their strong business models, these companies exhibit the qualities that are becoming the key to success in chemicals.

Rethinking the Approach to Emerging Markets. The Western chemical companies operating in emerging markets would do well to try to replicate some of those success factors. But they also face challenges rooted in their own practices and management approaches.

As 2016 unfolds, Western companies should consider the following approaches, extrapolated from BCG’s six-pronged Smart Simplicity framework.

1. Get closer to local markets. Chemical companies will never be perfectly organized to cope with the differences between one emerging market and another—there is too much complexity in their products and value chains. Consequently, managers should spend less time on organizational design and lengthy planning processes, and more time increasing their understanding of customers and the local business community. Incentives that drive these market-focused behaviors are crucial.

2. Give managers the power to make changes. Western chemical companies in emerging markets invest an inordinate amount of time debating the size of various markets and their own shares, and making presentations on these topics. Managers should have the discretion to curtail some of this work and to reallocate resources to business development and building supplier and distributor relationships. The proliferation of staff in departments with titles like Strategic Marketing, Regional Marketing, and Industry Marketing should be a red flag.

3. Introduce more autonomy. Chemical companies tend to be centralized in their decision making. In some ways and for some activities, that makes sense. In emerging markets, however, local sales and marketing executives need to be able to make their own decisions about customer prioritization, commercial terms, and technical account development. Distributing decision-making responsibility among multiple leaders can also prevent any one leader from amassing too much power. The autonomy imperative is not so much about broad decentralization as it is about adding power in a few strategic parts of the organization.

4. Push expatriate managers to think long term. For all the lip service given to the importance of overseas assignments, most up-and-coming executives don’t want these positions, which can disrupt their personal lives and even their career trajectories. For their part, chemical companies usually limit foreign postings to three years, inadvertently reducing the expatriate executive’s motivation to learn the language or put down roots in the local business community.

Chemical companies should lengthen rotations in emerging markets and implement policies to increase executives’ job satisfaction and chances of success. On the professional side, such policies could include greater tolerance for mistakes (a move away from the “no second chances” appraisal process), the inclusion of managers in succession planning, and bonuses linked to performance on local language tests. On the personal side, the policies could include more-flexible holiday schedules and more-generous travel accounts for families.

5. Look for ways to break down silos in emerging-market operations. Managers can become rooted in their thinking and resistant to outside input. Recruiting and promotion based on loyalty, not merit, worsens this. One European chemical company addresses the issue by recruiting a certain share of non-Chinese executives who know the language and the culture. The company looks for team members—regardless of their nationality and formal technical skills—who can challenge the sometimes ethnocentric perspective of local executives.

6. Reward those who cooperate, not those who primarily look out for themselves. Cooperation doesn’t always come naturally in companies. Far too often, managers concerned about their own short-term career interests filter the information that flows to the rest of the organization. This can be an especially big risk in overseas operations, where there is typically less headquarters oversight. If career success at a company can be achieved by controlling information and influencing the design of KPIs, that’s a problem. Instead, Western chemical companies operating in emerging markets should reward managers and executives who put their energy into building successful businesses. Such rewards won’t guarantee higher shareholder returns, but they are a start.

Given the disappointing results of the past few years, it isn’t a surprise that Western chemical companies are questioning their presence in emerging markets and wondering if there’s a way to reduce their exposure. Poor performance is never a confidence booster. However, multinational chemical companies must continue to treat China as a priority. Emerging markets are the future for these companies, and no country matters more to that future than China. Not to be there is to relinquish scale and to risk being cut off from innovation. China is the equation that every multinational chemical company must solve.