For a supply chain executive in the consumer packaged goods (CPG) industry, it’s a familiar situation. A company, as it pursues an ambitious growth strategy, must adapt its business model to enter new and expanding channels. It also must innovate to spur growth in an otherwise low-growth environment. For its supply chain team, all of this means working even harder to make a network built for scale more agile and cost-effective. At the same time, the team must keep up with the unrelenting service demands of the company’s retail customers.

Across sectors, CPG companies today face daunting strategic and operational challenges. Providing a high level of service to a growing number of customers and channels is imperative to drive growth. But doing so amid the capacity constraints of transportation providers is difficult. Many CPG companies are finding that even with a “service at any cost” attitude, the tried-and-true tactics for boosting service are no longer working. Indeed, the logistical obstacles have taken a measurable toll on CPG companies’ performance in terms of service levels, costs, and inventory.

Just how much are these challenges affecting CPG companies’ performance—and how are they driving planning and decisions about the future? The 2015 Supply Chain Benchmarking Study, produced by the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) and The Boston Consulting Group, examined the performance of leading grocery manufacturers’ supply chains to explore recent trends, practices, attitudes, and expectations.

This report crystallizes the top trends that emerged from the study, which involved 40 U.S. businesses of leading CPG companies. (See “About the Study.”)

About the Study

The 2015 Supply Chain Benchmarking Study, conducted by BCG and GMA, is the fifth in GMA’s benchmarking series on manufacturers’ outbound supply-chain logistics and is based on four components: surveys of 40 leading CPG companies (including one on supply chain logistics and one on direct store delivery), interviews with more than 70 supply-chain leaders and retailers, audience polling at the 2015 supply-chain conference sponsored by GMA and the Food Marketing Institute, and interviews with industry experts.

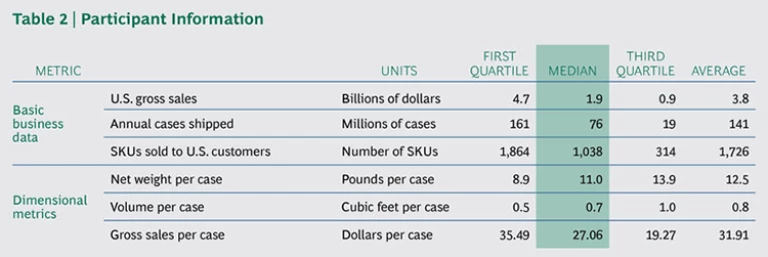

Participants included manufacturers of food, household, and beauty products with ambient and temperature-controlled (both refrigerated and frozen) supply chains. Many participants are multinationals, but the data collected was confined to their U.S. operations, for which annual gross revenues range from $70 million to more than $30 billion.

The CPG Environment: Limited Growth and Marketplace Complexity

Over the past several years, CPG companies have introduced an abundance of new products and innovations, yet, in aggregate, these efforts haven’t driven significant growth across the industry. The proliferation of new SKUs, along with shorter product life cycles, has increased portfolio complexity. At the same time, CPG companies must adapt to growing marketplace complexity: nontraditional sources of growth (such as convenience stores, dollar stores, and drugstores as well as the rise of natural and organic products) are changing the priorities and requirements of the supply chain as leading CPG companies respond to the diminishing dominance of the mainstream grocery channel. These shifts are expanding the points of sale and altering product flows.

Meanwhile, another source of marketplace complexity—the Internet—has created “endless aisles” by multiplying the assortment of available products. By leveling the playing field, the Internet is helping the Davids beat the Goliaths. Since 2009, smaller manufacturers have captured $13 billion in sales from larger CPG competitors.

The operational environment is no less challenging. Capacity constraints have made transportation a major headache for supply chain leaders. And because the underlying causes are structural—persistent driver shortages, aging highway infrastructure—these problems cannot be quickly alleviated. On top of the transportation challenge, a recent spate of mergers and acquisitions has forced many CPG companies to tackle supply chain network redesign. While they grapple with these operational complexities, supply chain leaders are often still expected to deliver substantial year-over-year savings.

Intensifying Performance Pressures

In recent years, the supply chain has been a steady source of efficiencies for CPG companies. But in the two years since our previous study, these efficiencies have been largely neutralized, as rising freight costs have consumed the savings generated elsewhere in the finished-goods supply chain. Less than half of the companies we surveyed for this study managed to reduce costs, and many experienced significant increases.

Logistics savings were eroded by transportation cost increases of 14 percent, improvements in forecasting accuracy have not consistently led to lower inventories or better case-fill rates, and efforts to boost service by setting higher service targets did not bear fruit. CPG companies’ on-time delivery rates declined precipitously; more than 60 percent of companies failed to meet their delivery targets.

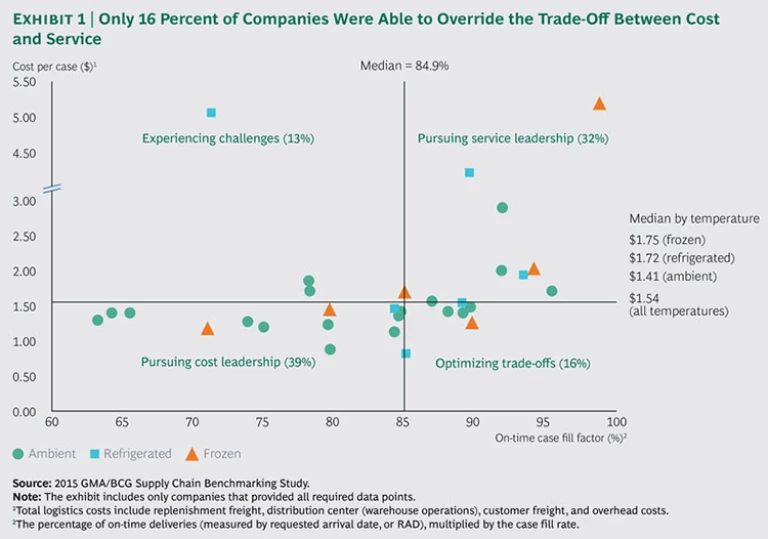

The difficult operating environment affected participating companies to varying degrees, creating wide performance disparities across the range of metrics. Only 16 percent of respondents exceeded the median on-time case-fill factor while also reporting below-median cost per case. (See Exhibit 1.)

The Top Six Trends

This year’s study revealed six clear trends:

- Transportation has become the top concern for 83 percent of supply chain leaders.

- Network redesign has soared in importance, becoming a top priority of nearly three-quarters of supply chain leaders.

- Freight costs are rising (by 14 percent since our 2013 study).

- Service is suffering; this held true across all measures.

- Inventories are growing (by 22 percent since our last study).

- Forecasting accuracy has improved, but it hasn’t yielded the benefits that companies had hoped to achieve.

These findings suggest that the traditional levers for performance improvement no longer work. Because they are wrestling with significant systemic changes, CPG companies need to think more strategically about their supply-chain network and operations.

Transportation is now the number one concern. In the The New Mission for IT in Consumer Packaged Goods , transportation didn’t receive a single mention as a top-of-mind issue. Today, 83 percent of supply chain leaders call it their greatest concern. Harsh weather in early 2014 (particularly in the northeast U.S.) elevated this concern. But it is clear that the dramatic change in priority is prompted by more-fundamental issues, such as cost increases and the growing difficulty of securing carriers.

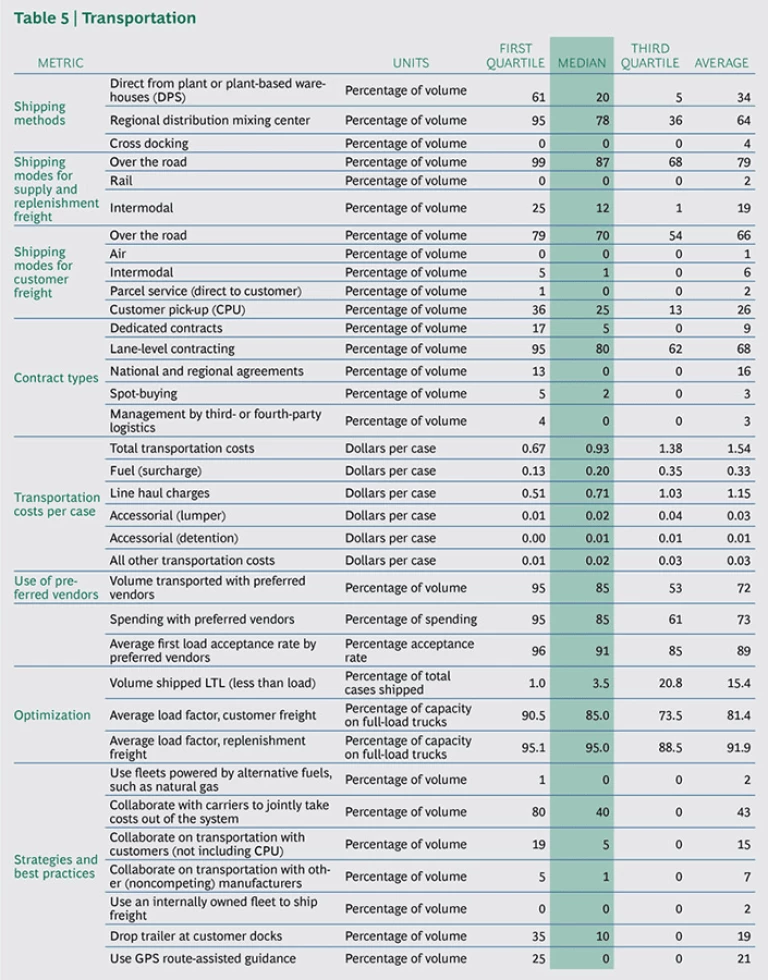

Once, fuel price volatility was supply chain leaders’ main transportation headache; today, their chief aggravations are capacity constraints and cost escalation in line haul rates—structural and apparently lasting challenges. Underlying these challenges are two external factors: driver shortages and an aging highway infrastructure, both systemic problems with no ready solutions.

The confluence of these pressures is not only eroding the hard-won cost and efficiency gains of recent years but also ultimately hurting on-time delivery rates and companies’ ability to meet service expectations. (See A Hard Road: Why CPG Companies Need a Strategic Approach to Transportation , BCG Focus, July 2015.)

Network redesign rose dramatically in importance. Network redesign ranked as the top concern of 72 percent of respondents in 2015. Just two years ago, only 6 percent of respondents mentioned network redesign as a concern. This dramatic rise in importance can be attributed to four developments:

- Greater postmerger integration activity, triggered by increasing industry consolidation as large companies seek to manage top-line challenges through cost synergies or by acquiring smaller, growing brands

- Higher transportation costs

- The desire for more efficient and more carrier-friendly routes to market

- The recognition that fast-growing new channels (such as convenience stores and online outlets) present different operational and shipping challenges

Many supply-chain leaders are studying their networks, seeking opportunities to optimize them. At a handful of leading companies, supply chain leaders are going one step further: exploring the shift to more flexible networks. They recognize that a rapidly changing environment—with shifting channels and transportation capacity constraints—means that network design cannot be regarded as a static plan. To achieve strategic objectives amid the new marketplace realities, networks must be reviewed and adjusted more frequently. But because it touches on so many internal elements—supplier management, customer management, technology, logistics, people, processes—redesign can be complicated. It also requires long-term thinking about how the markets will evolve.

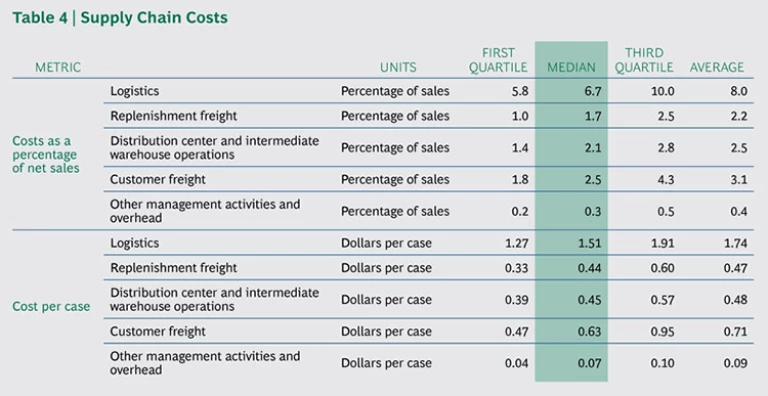

Freight costs continued to climb. Median freight costs have risen by 14 percent across all temperature modes. Thanks to cuts in other areas, most CPG companies were able to offset the increases enough to keep overall logistics costs relatively flat.

Costs differed by freight temperature, however. For ambient shipments, the industry median rose 11 percent, from $0.88 to $0.97 per case. One major reason: CPG companies’ relationships with ambient carriers have traditionally been transactional, and in a robust economy, CPG companies have enjoyed competitive rates. But as capacity has gotten squeezed, the transactional nature of those relationships has turned into a disadvantage because ambient CPG freight competes with freight from many other industries. As a result, more and more CPG companies are moving to a core carrier strategy, or at least expressing interest in becoming a customer of choice.

Although temperature-controlled goods are generally costlier to ship, freight costs for this category grew only 2 percent. Many temperature-controlled carriers are regional, so they serve a smaller pool of customers. Moreover, given their customers’ more specialized requirements, these carriers tend to have longer-term relationships with them.

Looking ahead, the overwhelming majority of respondents (83 percent) expect line haul rates to increase. Because line haul rates represent almost three-quarters of transportation costs—the other costs being fuel, lumper service (unloading of freight by a third party), detention, and other accessorial costs (such as tolls)—transportation costs overall are also expected to rise further.

About 60 percent of CPG companies are planning to increase their use of direct plant shipping (DPS), in response to rising freight costs. However, contrary to common belief, the data suggest that DPS is not necessarily the silver bullet. Although touted as a way to simplify shipping and cut mileage, DPS can actually complicate inventory management, routing, and loading, according to industry experts. In addition, companies that ship greater volumes through DPS tend to have poorer on-time delivery (requested arrival date, or RAD) performance. Some retailers we interviewed dislike DPS because they claim it is less reliable. As one observed, “The suppliers that impress us are moving away from DPS and bringing their inventory closer to our distribution centers.”

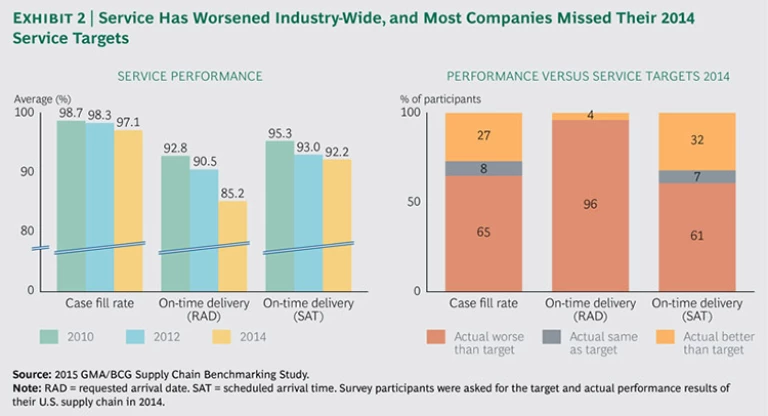

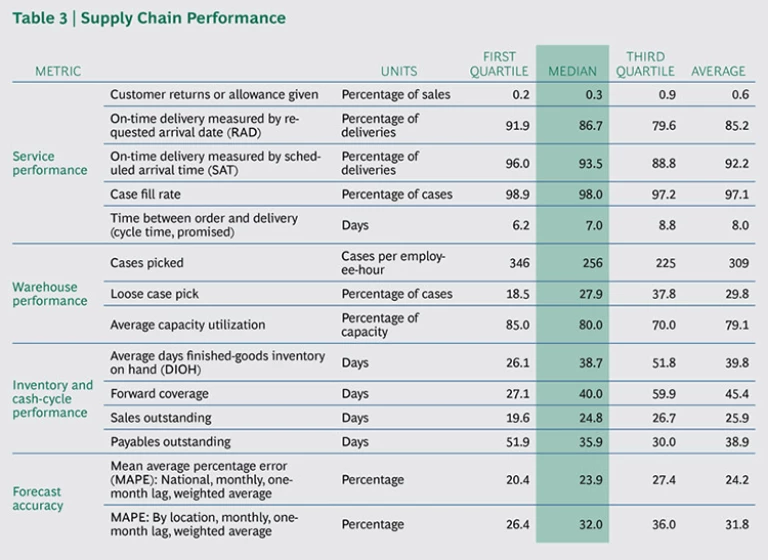

Service levels declined. By every key measure, service has grown progressively worse in the past few years. (See Exhibit 2.) After peaking in 2010, service had fallen by 2012, and it continued to decline into 2014 at an accelerated rate. Moreover, the performance gap between the best and the worst performers widened.

Bad weather was a factor especially in early 2014, but the main reasons were transportation related: truck and driver shortages that created unreliability and caused delays, coupled with congestion along routes and at delivery points.

Median case-fill rate and one measure of on-time delivery, scheduled arrival time (SAT), both decreased by about 1 percentage point. Declining SAT performance reflects, in part, worsening congestion. The steepest drop occurred in RAD, the other main measure of on-time delivery. Since our last study, RAD fell from 90.5 percent to 85.2 percent. The RAD drop clearly shows how severe the industry’s capacity problems have become.

Most CPG companies missed every key service target in 2014. A stunning 96 percent missed their RAD targets. If achieved, the targets would have led to improved service levels. So, were these targets overly ambitious? Possibly. But there is no denying that capacity constraints are hurting service.

CPG companies are keenly aware of the cost-service trade-off. Although some are adhering to a strategy of “service at any cost,” others are seeking their own optimal balance of cost and service. Still others appear to have been caught off guard by the extent of the transportation difficulties and have had to deal with the fallout from disgruntled customers.

Inventories grew, despite the focus on working capital. Ambient CPG shippers suffered another reversal in 2014. Despite the improvement in forecasting accuracy and the focus on working capital over the past few years, inventories rose. Approximately 70 percent of ambient companies experienced inventory increases, as companies held more safety stock to offset transportation bottlenecks or build buffers to maintain steady supplies during their network-redesign work. For ambient companies, median days of inventory on hand grew by 20 percent, from 35 to 42 days, since the 2012 survey. Within that 70 percent, the gap between the high and low performers widened significantly.

Since 2012, the accuracy of CPG companies’ national forecasts increased 1.4 points, from 73.6 percent to 75.0 percent. There are two explanations for this apparent contradiction: The national averages could be masking inaccuracies at the local level. (See the next section, “Forecasting-Accuracy Gains Haven’t Yielded Desired Benefits.”) Or, CPG companies simply sought to ensure against delays caused by the transportation network or incurred during a network redesign.

For temperature-controlled shipments, the story is mixed. Sixty percent of temperature-controlled shippers experienced inventory increases, but the median actually declined.

Regardless of the type of goods, CPG companies know well the cost of holding excess inventory—perhaps most important, the negative effect on the cash conversion cycle. But other levers in addition to inventory can be applied to limit the effects. A few CPG companies in our study actually managed to establish a negative cash-conversion cycle. Many companies might follow their lead and pursue the opportunity to dramatically shrink the cycle. (See “There’s More to Working Capital Than Inventory.”)

There's More to Working Capital Than Inventory

Every CPG supply-chain leader strives to minimize inventory levels. But some realize that they have more levers at their disposal for managing the availability of cash, as measured by the cash conversion cycle (CCC), which can be represented as the following equation: CCC equals days of inventory on hand (DIOH) plus days of sales outstanding (DSO) minus days of payables outstanding (DPO). Or:

CCC = DIOH + DSO - DPO

To illustrate, consider Grainville, a fictitious cereal maker. Sugar is one of Grainville’s main inputs. Instead of maintaining a low DPO, Grainville could extend the time it takes to pay its sugar provider (for which it is an important customer), thus gaining additional days’ worth of cash.

With this extra cash, Grainville could adopt any one of a number of strategies. It could increase inventory to improve case fills or “fund” a more favorable DSO for its customers. The latter approach would no doubt make Grainville a hero in their eyes.

Certainly, before adopting such a strategy, CPG companies should proceed with caution, because increasing DPO can have adverse consequences: suppliers could, for example, reduce discounts, raise prices, or cut service levels.

The point is, rather than view such cash-management decisions as solely the province of the accounting department, strategic supply-chain leaders should consider them part of the tool kit for freeing up working capital—and doing so in a way that might both enhance service and bolster customer relationships.

Many CPG companies are taking a closer look. Although inventory increased by four days across our survey participants and DSO increased by three days, these negative effects were mostly offset by an increase in median DPO of six days.

Forecasting-accuracy gains haven’t yielded desired benefits. Streamlined inventories weren’t the only unrealized goal of more accurate forecasting. Service did not improve, either. Audience polling at the February 2015 supply-chain conference sponsored by GMA and the Food Marketing Institute identified several reasons, but the two most common were last-mile transportation challenges (26 percent of respondents) and less accurate local forecasts (22 percent). Each, of course, has unrelated root causes.

Among participants that track local forecast accuracy, the average forecast accuracy for ambient goods was slightly more than 67 percent—8 percentage points lower than the national rate. At the national level, accuracy rates are always higher because they represent broader averages. National results thus mask regional misses.

Apart from tackling local forecasting accuracy, another way to improve forecasting is through product segmentation. Seventy percent of interviewees already use a different forecasting approach for different SKUs—based on such characteristics as product velocity, margin, and lead time. Segmentation by product is the most common approach, but some companies also segment by customer (59 percent), channel (41 percent), or store (11 percent).

Even when CPG companies have inventory in the right place at the right time, last-mile transportation challenges may keep them from getting it to retailers on time. Last-mile transportation challenges refer to the collective external systemic problems that CPG companies face: capacity constraints (from driver shortages and insufficient truckload volume) and over-the-road congestion and delays, both on routes and at delivery points. Minimizing these difficulties calls for a comprehensive, multifaceted set of tactics involving mode selection, efficiency, route design, and partnerships with carriers, customers, and even other shippers.

Winning Today Requires an Enterprise View

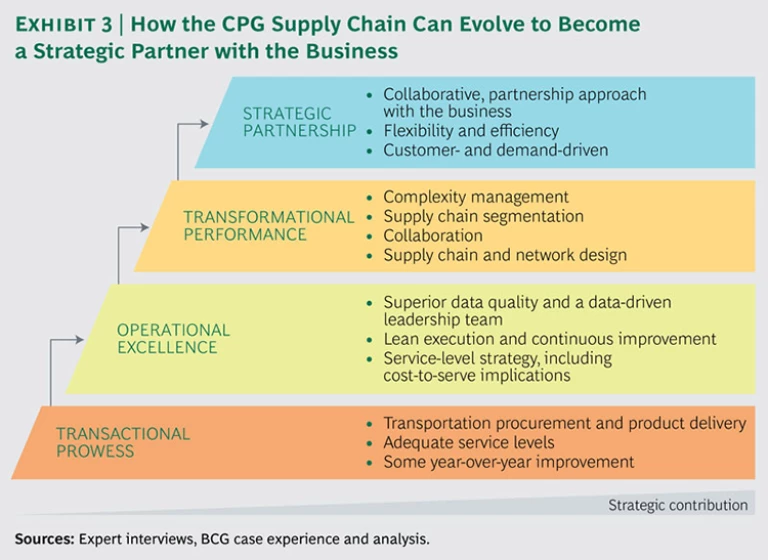

The disappointing industry results reflected in this year’s top trends are hardly a sign of complacency. What is clear, however, is that supply chain leaders face operational challenges today that require enterprise-wide solutions. Traditional best practices are no longer enough. The magnitude, long-term nature, and impact of these challenges, in combination with the broader business challenges that CPG companies face, call for a more strategic, more collaborative supply-chain approach. Exhibit 3 illustrates the progression in the approach to supply chain management: from transactional prowess to operational excellence to transformational performance and, ultimately, to strategic partnership, where the supply chain works in concert with the business.

As noted, 16 percent of CPG companies are managing to overcome the cost-service trade-off. Interestingly, they represent a diverse mix: companies big and small, with products that range from food to beauty and that cut across temperature modes. These CPG companies’ success has little to do with who they are, and everything to do with how they manage.

More important, companies can tweak the cost-service trade-off to strike the balance most appropriate to them. Not every company needs to fall within that 16 percent to be successful. Success for some companies might primarily mean reducing costs or becoming a service leader. Moreover, not all products within a single CPG company’s portfolio are created equal. The trade-offs might shift across product or customer lines.

Supply chain exemplars have already mastered performance basics. They’ve implemented operational-excellence practices, such as data gathering and analysis, lean execution and continuous improvement, and service-level strategy. Now, they are engaging in activities that can create a step change in areas such as complexity management, supply chain segmentation, collaboration, and network redesign. Achieving optimal results from these activities requires recognizing the interdependencies and impacts of a more holistic, more collaborative approach across the organization.

The experience of the past two years demonstrates that, in many respects, the sands have shifted for the CPG supply chain. Amid rapidly changing customer dynamics, evolving portfolio profiles, and an increasingly challenging transportation environment, exemplary supply-chain leaders are employing new tools and strategic approaches to keep cost pressures at bay—and enable enterprise growth.

Appendix

Acknowledgments

The research described in this report was sponsored by GMA’s Supply Chain Committee and was performed by BCG in partnership with GMA. The authors would like to thank the members of that committee as well as Daniel Triot, senior director at the Trading Partner Alliance.

In addition, the authors would like to offer their sincere thanks to their BCG colleagues Demi Horvat, Katherine Jones, and Laura Sluyter. They also thank Jan Koch for assisting with the writing of this report. Thanks also go to Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Catherine Cuddihee, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, and Sara Strassenreiter for their contributions to editing, design, and production.