Both Maersk Group and PulteGroup are examples of companies that used a focus on value creation to jump-start a far-reaching organizational and business transformation . Such a focus can be an extremely useful lens for determining whether transformation is necessary, creating a sense of urgency, and then organizing a company’s efforts. (See “The BCG Transformation Framework.”)

THE BCG TRANSFORMATION FRAMEWORK

In our work supporting business transformation at companies around the world, we have developed a simple but powerful framework to help companies create sustainable improvement in performance.

The approach addresses three critical parts of transformation—funding the journey, winning in the medium term, and building the right team and culture—in order to support strong, long-term value creation.

The exhibit below illustrates how specific issues of value creation strategy—including portfolio restructuring, investor strategy, and financial strategy—fit into this overarching framework.

Is Transformation Necessary?

Maersk and Pulte each faced a severe crisis that put the survival of the company at stake. But most situations aren’t so black and white. To determine whether your company needs to transform its value-creation strategy, you must first ask yourself, “Is transformation necessary?”

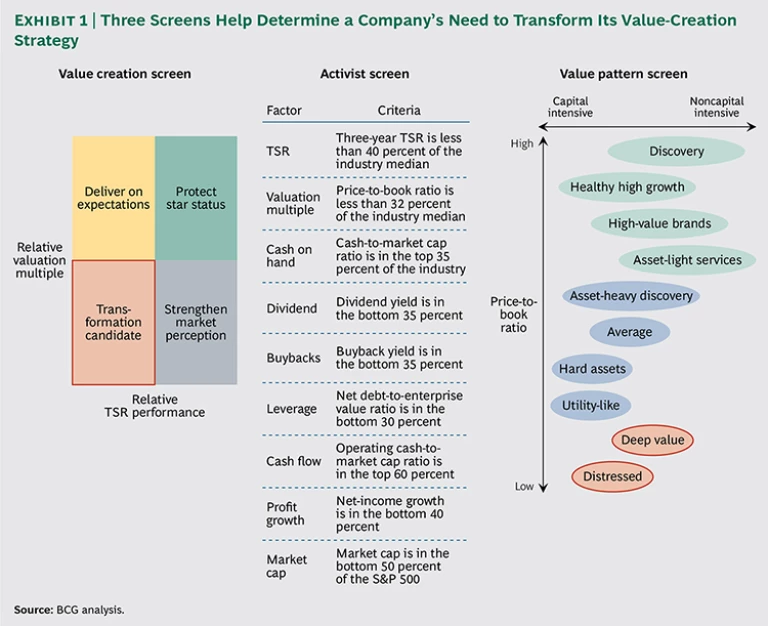

BCG has developed a variety of screens that a company can use to answer this question. (See Exhibit 1.) The value creation screen, on the left-hand side of the exhibit, compares the company with its peers or with some appropriate market index across two dimensions of value creation performance: the company’s recent TSR performance relative to its peer group or industry average (on the x-axis) and the company’s valuation multiple relative to the peer group or industry average (on the y-axis). The first of these dimensions looks backward to see how the company has done in the recent past. The second looks forward to see how investors think the company will do in the future, based on their expectations as reflected in the company’s valuation multiple. Companies that lag their industry or peer group on both dimensions are candidates for transformation. (See Turnaround: Transforming Value Creation , the 2014 BCG Value Creators report, July 2014.)

We developed the activist screen in Exhibit 1 in response to the increased activity on the part of so-called activist investors in recent years. (See “Do-It-Yourself Activism,” BCG article, February 2014.) We analyzed the performance of U.S. companies that have attracted an activist investor campaign and identified the critical thresholds across nine metrics that increase the odds that a company will face an activist campaign. So, for example, activists tend to target companies whose TSR over a three-year period is less than 40 percent of the industry median, whose valuation multiple is in the lower third of its sector, and whose cash on hand is roughly in the top third. If a company meets these criteria, along with the others in the activist screen, its senior executives should be thinking about transforming its value-creation strategy—before some activist investor does it for them.

Of course, even successful companies will sometimes need to reshape their value-creation strategy. In recent Value Creators reports, for example, we have featured the new BCG concept of value patterns—distinctive company starting positions that cut across industry boundaries and shape the range and types of strategic moves most likely to

Six Steps Toward TSR Transformation

If your company has determined that it needs to transform its value-creation strategy, you can do a number of things to make it happen. BCG has identified six key steps for TSR-driven transformation.

Set your ambition. The key starting point is how you define success. Partly, that’s a matter of setting your level of ambition. In our experience, most senior executives think in terms of achieving top-third or top-quartile performance in their peer group or, like Pulte, setting goals such as “tripling the stock price in five years.”

Starting with an ambitious goal of this sort can be useful to get an organization to take a critical look at its past performance and future plans. The value of an ambitious target is that it immediately gets managers thinking, “How are we going to achieve that goal?” But keep in mind that it is extremely difficult to consistently achieve something like top-quartile performance. Indeed, it is difficult even to routinely beat the market average.

So senior executives will need to be prepared to test their stretch goals against the realities of their companies’ competitive positions and organizational capabilities, as well as against the expectations of investors. In our experience, the result of this process is often to scale back the value creation goal to a more modest level. But that’s not necessarily a disaster. The good news is that if a company succeeds in delivering TSR that is just 2 to 3 percentage points above average year after year, such a performance can add up to top-quartile TSR over the long term.

Choose the right metrics.The next step is to choose the right metrics, which will tell you whether or not you are achieving your ambition. Not all dollars of free cash flow are created equal. Different ways of achieving cash flow are valued differently by investors, with varying impacts on TSR. Optimizing a company’s value-creation strategy is a matter of managing trade-offs—for example, between investing in growth and investing in margin improvement, between growing organically and growing through acquisition, between maintaining gross margins and reducing operating expenditures. Therefore, it’s critical to put in place the right metrics that make the key trade-offs in a company’s value creation visible so that senior management can navigate them effectively. A key step in both the Maersk and Pulte transformations was to start measuring company and unit performance using value-based metrics, such as TSR.

These metrics are important not only for tracking a company’s past performance but also for identifying future initiatives that will fund the company’s transformation journey. By translating its business and financial plans into estimates of future contribution to overall company TSR, a company can assess its future value-creation potential at the level of individual businesses and strategic initiatives. With a clear view of future TSR potential by product, business, region, and initiative, companies are in a better position to identify which initiatives will really move the TSR needle, debate alternative pathways to superior value creation, and target improvements in their business plans.

Define the portfolio strategy. A transformative value-creation strategy also depends on a clear portfolio strategy and active portfolio management. Both are critical to determining how the company will win in the medium and long terms. Each business in the corporate portfolio needs to have a clearly defined role. Do you know which businesses will be your future growth engines? Which will mainly supply cash for other businesses to invest? Which you will need to turn around or consider selling?

What’s more, capital and other resources—such as managerial talent—need to be allocated differently across the corporate portfolio on the basis of each unit’s current performance, future potential, and role in the value creation strategy. A key step in Maersk’s transformation was the creation of stand-alone business units, each with different roles in the overall portfolio.

But active portofolio management isn’t necessary only at multibusiness conglomerates such as Maersk. At PulteGroup, for example, the key portfolio to manage was the one of market positions in different geographic areas. The company had to make sure that capital allocation favored markets that were not already overbuilt and in which Pulte had a strong share relative to its competitors. Nearly every company has a portfolio—be it geographic markets, products, R&D pipelines, or business units—that it needs to actively manage to optimize value creation.

M&A and divestitures are critical parts of active portfolio management. Acquisitions are an important way to strengthen existing businesses or expand into new ones. (See Unlocking Acquisitive Growth: Lessons from Successful Serial Acquirers , BCG Perspectives, October 2014.) Meanwhile, selling businesses that no longer fit in a portfolio can improve its value-creation potential. (See Don’t Miss the Exit: Creating Shareholder Value Through Divestitures , BCG report, September 2014.) For example, Maersk used divestiture to bring more focus to its portfolio, then reorganized to create five focused business units with clear roles and accountability for different aspects of the company’s business.

Align the financial strategy. Most transformation efforts at large companies focus on business strategy, operations, and technology. It’s equally important for a company’s financial strategy to be aligned with the company’s long-term objectives. Because financially healthy companies generate cash well in excess of their reinvestment needs, they need to have a plan for what to do with the excess cash. That involves striking the right balance between cash kept on the balance sheet, share buybacks, and dividends returned to investors while also considering the optimal capital structure and credit rating. Getting that balance right is a powerful way for companies to create alignment with their investors. What’s more, these alternative uses of capital have a direct impact on TSR and an indirect impact on a company’s valuation multiple. Therefore, decisions about a company’s financial policies need to be an explicit part of the company’s value-creation strategy.

At Maersk, for example, a key part of the new value-creation strategy was to substantially increase the company’s dividend. The increase was a signal to investors that Maersk had shifted its investment approach from the traditional focus on pure growth to one that emphasized balanced growth at a reasonable price.

Target the right investors. A successful value-creation strategy also needs to reflect the priorities and expectations of a company’s most important investors. Sometimes that means listening carefully to what your current investors want. Other times it means migrating the investor base to new types of investors who are more likely to be in sync with management’s business and financial strategies. In either case, it is important to start thinking of investors the way a company thinks of customers. That is, segment investors into categories based on investment style and priorities, and identify the “natural” investor type for the company. Consider the following key questions:

- Who are our dominant investors right now?

- Are they the ones who are likely to support our value-creation strategy in the medium and long terms?

- Do current or desired investors find the company’s strategy credible?

- What can we do to create better alignment among our business, financial, and investor strategies?

At Maersk, the natural investor segment for the company’s stock consisted of funds that pursued a strategy of growth at a reasonable price. To appeal to the priorities of this type of investor, the company had to make moves such as developing the more value-focused capital-allocation policy and generating large dividend increases.

Refocus management processes. A company’s value-creation strategy is only as strong as its value-management capability, which drives a company’s processes and organizational culture. The final step in a TSR-driven transformation is to focus key management processes—such as target setting, planning, resource allocation, and incentive compensation—on TSR and to create strong links to value creation at the level of the individual business unit. (See The Art of Performance Management , BCG Focus, March 2015.) This is a critical component of the cultural change effort in any broad-based organizational transformation.

By following these six steps, any company can use a focus on value creation to drive a broad-based business transformation, just as Maersk and Pulte have done. The result: better financial performance, above-average TSR relative to the company’s peer group, and improved positioning for success in the future, regardless of economic conditions or market environment.