In today’s increasingly complex business environment, addressing the perennial challenge of controlling the costs of support functions has become more important than ever. Likewise, the consequences of failure have become more serious—even for top-performing companies that have been relatively unscathed in the past. To compete in this more complex environment, companies must globalize operations, respond to rapidly changing customer requirements and regulatory demands, and pursue and defend against digital disruptions. These imperatives have made maintaining cost-competitive support functions even more crucial for long-term success and profitability. Indeed, high-performing support functions can mean the difference between winning and losing in extremely competitive markets and industries.

To thrive in this environment, companies need smart and simple support functions. Such functions deliver value-adding services, help the core business sustain competitive advantages, and facilitate executive decision making, while also being cost-efficient. To achieve these goals, leading companies have applied a holistic yet modular approach developed by The Boston Consulting Group called Exercising for Excellence, or

Support Functions Can Endanger Competitiveness

Why has providing high-quality support services at sustainably low costs proved to be such an elusive goal for many companies? One reason is that the value that support functions create—or destroy—can be hard to identify. The benefits or waste are typically hidden in information flows and systems and dispersed over several locations. By contrast, the value that core functions produce or erase can readily be observed. Efficient manufacturing operations, for example, can quickly be identified, as can underutilized equipment and overflowing warehouses.

At the same time, keeping costs under control is hard, because inefficiencies are notoriously difficult to measure and often reflect long-standing cultural habits within a company. Furthermore, individual employees may not have an incentive to eliminate these inefficiencies and may even benefit from their existence. Some employees may create processes, workflows, or reports to add to their own responsibilities and build up their department’s staff, even if the business value created does not exceed the additional cost. To make matters worse, some companies have taken a “more is better” attitude when it comes to adding product variants and new systems and processes, whether to satisfy customers or internal clients. Unfortunately, it is usually easier to add these customized products and services than to manage the resulting increase in costs.

Although the causes of waste or inefficiencies in support functions are hard to identify and control, the symptoms are well known: Byzantine processes, multiple IT systems, unread reports, marathon meetings, and seemingly endless red tape. Instead of enhancing competitiveness, support functions often burden organizations with unnecessarily high costs and low productivity, while an unyielding bureaucracy causes employees to become increasingly disengaged and frustrated.

Companies recognize the importance of improving the performance of their support functions. Too often, however, management focuses on superficial cost cutting rather than using a comprehensive approach that reduces unnecessary costs while adding services that are valuable to business units or operational functions.

Cutting resources can be an effective way to mobilize support functions and force them to refocus on value-added activities. However, to reap the full benefits of painful onetime cost cutting, the organization needs to sustainably change how activities are prioritized and executed. Otherwise, the workload is likely to remain essentially the same, and companies may eliminate resources that are essential for undertaking value-adding initiatives in a fast-changing business environment. What happens next is all too common: the costs and resources of support functions creep back to their previous levels—until the next cycle of cost cutting trims them yet again.

BCG’s research sheds light on the extent to which companies have endangered their competitiveness by failing to transform their support functions into value-adding units and achieve sustainable cost efficiency. (See “Most Fortune 500 Companies Lack Smart and Simple Support Functions.”) We found that declining business profitability is often accompanied by rising costs in support functions.

MOST FORTUNE 500 COMPANIES LACK SMART AND SIMPLE SUPPORT FUNCTIONS

Do leading companies position themselves to maintain a long-term competitive advantage by sustainably reducing the costs of support functions? To answer this question, we analyzed the Fortune 500 companies and categorized them on the basis of two factors. (See the exhibit below.)

- The development of their business profitability, measured as the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of their operating margin

- The development of the cost of their support functions, calculated as the CAGR of their sales, general, and administrative expenditures relative to their total costs

Higher business profitability combined with declining costs for support functions indicates that companies benefit from smart and simple support functions that facilitate value-adding decisions at the corporate level and in business units. Our analysis found that only 23 percent of Fortune 500 companies have achieved this favorable scenario. These companies should not rest on their laurels, however. They have an opportunity to enhance their competitive advantage by taking steps to sustain their improvements to support functions and by taking smart approaches to adapt to the ever-more complex business environment.

The remaining companies face the types of obstacles to sustainable business success that the X4X approach can help resolve.

For 21 percent of the companies we analyzed, higher profitability was accompanied by an increase in the relative costs of support functions. These “effective but inefficient” companies could increase their operating margin by reducing the total costs of their core business or increasing prices to push revenues higher. Even if support functions’ higher relative costs do not appear to be a drag on profit growth today, their inefficiencies could significantly undermine future business performance, as the company seeks to adapt to changing external conditions in the dynamic environment.

Thirty-eight percent of the companies reduced the relative costs of their support functions, yet their business profitability contracted as well. This “efficient yet ineffective” performance can be attributed to superficial cost cutting that reduces or eliminates resources without regard to the value added by the related activities. Such quick one-off improvements do not translate into long-term benefits.

Finally, 18 percent of the Fortune 500 companies were “inefficient and ineffective”: unproductive work, wasteful bureaucracy, and complicated structures, among other factors, have combined to drag down profitability. These companies need to transform their support functions so that they add value while being sustainably cost efficient.

Our project experience provides additional insights into the detrimental consequences of failing to properly manage support functions. We have found that waiting time can consume up to 80 percent of the time required to complete support processes, which limits an organization’s agility and the quality of its outputs. For example, one company needed more than 150 days to complete the hiring process for new employees, and 65 percent of this time was spent on unnecessary activities. Long waiting times during the company’s hiring process resulted in roughly 50 percent of candidates turning down an offer.

Companies can often accomplish a process’s objective with up to 50 percent less resources. As a case in point, the resources devoted to preparing financial reports could be significantly reduced. Many of these reports are often too long and produced too frequently. The result is that up to 60 percent are unread. Moreover, many companies do not have standardized formats for these reports, which means that multiple iterations are typically required to prepare a finished product that, more often than not, simply collects dust.

Inefficiencies such as these can take a significant toll on employee satisfaction and engagement. In surveying employees during our projects, we have found that satisfaction and engagement are up to 50 percent lower in poorly performing support functions than in efficient ones. In some organizations, the rank-and-file employees are shut out of decision-making processes, receive little or no feedback, and do not see any impact from their efforts.

Smart Simplicity Helps to Overcome the Challenges

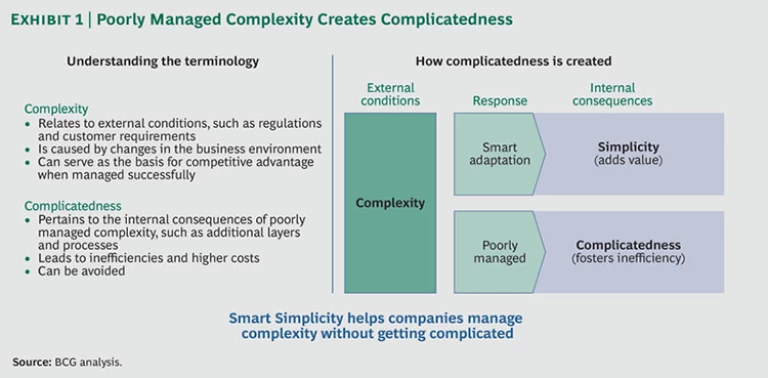

In searching for the root causes of support functions’ poor performance, management teams should focus their attention on how they have responded to the increased complexity of the business environment. To understand how the wrong response can create inefficiencies, consider the distinction between complexity and what we call “complicatedness.” (See Exhibit 1.) Complexity relates to external conditions, such as regulations and customer requirements, and can arise from changes in the business environment. Complicatedness pertains to the internal consequences of poorly managed complexity and can take the form of additional organizational layers, departments, and processes that management introduces to respond to complexity. Complicatedness leads to inefficiencies and higher costs for overhead that adds little or no value to the business. Complicatedness also undermines employees’ ability to intelligently manage external complexity, which makes it even harder for organizations to deal effectively with changes in the business environment. Hence, a complicated organization is the true opposite of a lean organization. As counterintuitive as it might sound, the more complex the environment, the simpler the organization needs to be.

Complexity is a fact of business life. However, by intelligently adapting to complexity, companies can avoid complicatedness and, instead, promote simplicity in the form of valued-added support services provided at optimal cost. Taking this smart approach to managing complexity is crucial to generating competitive advantages. When confronted by new complexity, a company can create competitive advantages by pursuing BCG’s

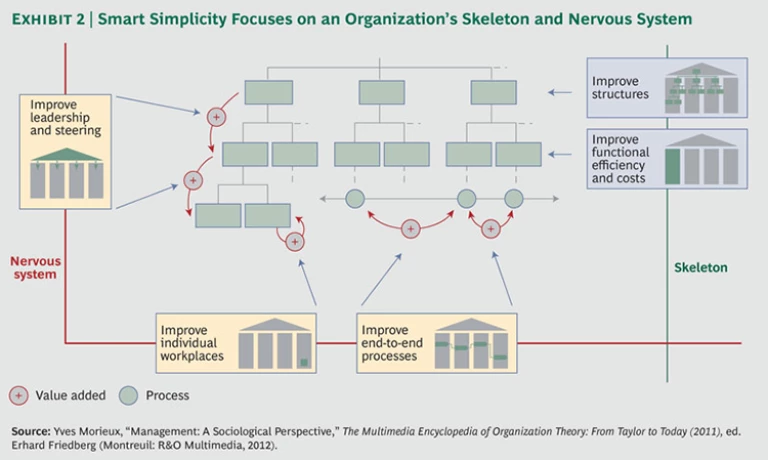

Another insight underlying Smart Simplicity is the importance of considering the organizational context in terms of both the “skeleton,” comprising the organization’s structure and functional resource allocation and accountabilities, and its “nervous system,” comprising its leadership, collaboration, and engagement mechanisms. The classic approach to transforming support functions typically focuses on the skeleton by seeking to improve structures and efficiency and costs. (See Exhibit 2.) In addition to addressing the skeleton, Smart Simplicity focuses on the nervous system by seeking to improve leadership and steering, collaboration along end-to-end processes, and engagement through improvements to individual workplaces and daily routines. The goal is to add greater value through management and execution and ensure that each employee’s behavior increases the effectiveness of colleagues.

Because of its comprehensive behavioral focus, Smart Simplicity is much more effective than the classic approach at fostering sustainable budget improvements across functions. As an example, consider how incentives can influence the trade-offs between design and maintenance costs. A company using the classic approach rewards its product design manager for keeping the department’s costs low. This approach steers the manager toward holding design costs to a minimum—without regard for the maintenance requirements of the resulting product. Consequently, the maintenance department’s budget soars, despite its manager’s best efforts to control costs. In contrast, a company applying the Smart Simplicity philosophy incentivizes the product design manager to ensure that the department devotes attention to the tough trade-offs between design and maintenance costs. For instance, the company could tell the product design manager that he or she will be transferred to the maintenance department when the product is released and will assume responsibility for the maintenance budget. Such incentives can promote a collaboration that enables sustainable reductions to both design and maintenance budgets.

Achieving Smart Simplicity with X4X

BCG has designed Exercising for Excellence, or X4X, as a holistic yet modular approach for applying Smart Simplicity to support functions. X4X reduces complicatedness throughout an organization and addresses common issues across functions, leading to significant yet sustainable cost reductions. Although companies can use X4X to make big one-off improvements to structures and costs, such improvements are just the starting point. The approach is distinctive for also enabling an organization to build and sustain its strength and competitiveness over time through continuous improvement and cultural change.

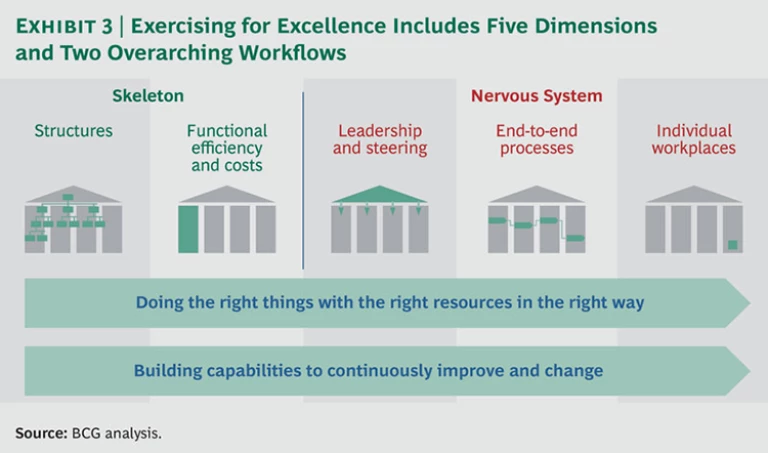

The X4X framework includes the five dimensions of Smart Simplicity as well as two overarching workflows. (See Exhibit 3.) Companies can apply the approach across each of the five dimensions or customize it to address challenges in a particular dimension:

- Structures. The X4X approach helps companies look for opportunities to remove unnecessary organizational layers, pool resources in shared service centers, and outsource or offshore commoditized tasks, among other measures.

- Functional Efficiency and Costs. By applying X4X to this dimension, companies can, for example, optimize service levels, eliminate duplicative services among functions, and cut unnecessary spending.

- Leadership and Steering. The X4X approach helps management define governance roles and mandates, remove unnecessary decision and approval gates, and set the right incentives and KPIs, among other initiatives.

- End-to-End Processes. The X4X approach guides companies looking for ways to, for example, reduce waiting times, standardize and reduce process variants, even out demand, automate manual work, and increase utilization.

- Individual Workplaces. Using X4X on this dimension, organizations can improve their effectiveness and efficiency by increasing each individual’s engagement and share of value-adding tasks performed, as well as the discipline with which each employee performs daily routines. Other measures at the individual level include clarifying accountabilities and roles within each team and minimizing unnecessary meeting time.

The two overarching workflows help organizations meet the twin challenges of achieving improvements quickly and then reaching continually higher levels of performance.

The first overarching workflow aims to promote step-change improvements by ensuring that an organization is doing the right things with the right resources in the right way. The “right things” are value-adding activities. The “right resources” are appropriately qualified staff, whether sourced internally or externally. The “right way” means using streamlined and standardized process, with only the necessary stakeholders involved. The second workflow focuses on building capabilities so that the organization not only continuously improves and changes but also sustains its accomplishments.

Central Coordination with Broad-Based Design and Delivery

The X4X approach is centrally coordinated and managed by a proactive and empowered program-management office (PMO), yet X4X is also designed and delivered in collaboration with all levels of the organization. This approach applies the strengths of the traditional top-down and bottom-up approaches to transforming an organization while overcoming their limitations. For example, a top-down approach confers the benefits of achieving significant impact in a short time period through structural change, central coordination, and rigorous target setting, but the broader organization often struggles to sustain improvements. A bottom-up approach fosters sustainable improvements by focusing on behaviors and collaboration, but the changes achieved by smaller initiatives might be too incremental and not integrated well enough to create synergies throughout the organization.

In the X4X approach, the PMO’s central coordination promotes transparency by comprehensively analyzing resources and uncovering inefficiencies and redundancies. The information gathered provides the basis for benchmarking and target setting. By centrally discussing targets, the PMO can define the program’s ambition organization-wide, gain the commitment of senior stakeholders, and facilitate a fact-based assessment of the savings potential. Involving the broader organization in the design and delivery of improvement measures and cost-reduction initiatives fosters shared ownership of the program’s success. Tracking the implementation progress of these measures and initiatives, supporting cultural change, and providing employees with the skills and tools for pursuing continuous improvement promote sustainable success.

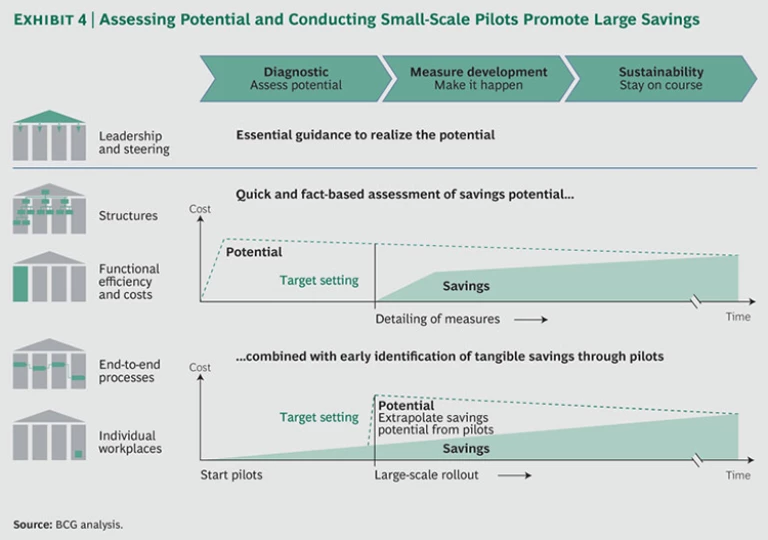

X4X has an integrated set of tools, which is used to implement cost-saving improvements in the organization’s skeleton and nervous system during each of the program’s three phases: diagnostic, measure development, and sustainability. (See Exhibit 4.)

- Diagnostic. The PMO uses a qualitative and quantitative diagnostic tool to assess the large-scale savings potential from improvements to structures and functional efficiency and costs. On the basis of a discussion of business requirements and strategic trade-offs and a review of company benchmarks, the PMO defines the program’s ambitions for large-scale savings, overall and by support function, and sets targets for achieving these ambitions. Concurrently, the PMO gauges the potential for tangible, smaller-scale savings from improvements to end-to-end processes and individual workplaces. Small pilots are used to test the impact of selected improvement measures. The early savings generated by these pilots are then extrapolated to formulate a target for the broader organization. In combination, the central assessment of potential and the extrapolation of pilot results allow for a holistic assessment of the savings potential available organization-wide.

- Measure Development. Next, the PMO develops measures, such as restructuring the organization or redesigning functional processes and interfaces, to achieve the large-scale savings potential. It sets out detailed measures in implementation roadmaps and establishes a system for tracking the impact. Concurrently, improvement measures successfully tested in the pilots are rolled out on a large scale. During this phase, the program begins to capture savings from improvements to structures and functional efficiency and costs. It also continues to ramp up savings from improvements to end-to-end processes and individual workplaces.

- Sustainability. In the third phase, the PMO focuses on how to ensure that the program stays on course. The PMO puts in place enabling tools and mechanisms and builds capabilities to promote continuous and sustained improvements. As the program reaches a higher level of maturity, the assessed potential for savings gradually decreases to coincide with the savings achieved.

The X4X approach and the associated tool set are designed to help companies apply and adhere to BCG’s “Six Simple Rules” for managing complexity without getting complicated. (See “How X4X Tools Bring Smart Simplicity to Support Functions.”) The tool set includes BCG’s advanced version of value stream mapping, which we have designed by applying the concepts of Smart Simplicity. (See “BCG’s Value-Stream Mapping 2.0.”)

HOW X4X TOOLS BRING SMART SIMPLICITY TO SUPPORT FUNCTIONS

Companies can use BCG’s Six Simple Rules to manage complexity3. The X4X approach and tool set are designed to help companies apply these rules to their support functions:

- Understand what your people really do. Companies need a comprehensive understanding of their employees’ work and why they do it. By providing transparency into what is really happening in an organization, X4X diagnostic tools help companies gain insights that are essential for target setting and measure development. For example, the activity-based optimization tool reveals how employees are dispersed across various processes and activities. These insights are complemented by socio-organizational interviews—a tool that helps companies understand how the organizational context influences employees’ behaviors and rational decisions.

- Reinforce integrators. Companies should increase the power of individuals to foster cooperation and refuse escalation. Through broad organizational involvement and shared project ownership, X4X increases managers’ power to accelerate processes and take responsibility without regularly escalating issues to the next leadership level.

- Increase the total quantity of power. Power is not a zero-sum game; companies need to create new power, not just shift existing power. That is why empowerment through X4X does not stop at the managerial level. The approach includes employees in the improvement effort, giving them tools—such as those that help implement new daily routines—to increase their power. In this way, X4X enables broader participation in decision making and makes processes more transparent.

- Increase reciprocity. As work becomes more interdependent, companies must take steps to make cooperation happen. Establishing the right incentives, processes, and structures to stimulate cultural change and desired behaviors is essential to fostering cooperation and enabling continuous improvement. For example, by basing individual evaluations on overall team performance or even cross-functional performance, companies can increase reciprocity among employees or functions and create a common interest in effective and efficient workflows.

- Extend the shadow of the future. Managers and employees need to understand that their actions today result in consequences that ripple through the broader organization tomorrow. They need to think beyond the narrow confines of their current role and function and consider how their actions will affect their colleagues in other roles and functions. Companies can bring the future closer by shortening feedback loops and designing career development paths that expose employees to other roles and functions.

- Reward those who cooperate. Companies must make clear that individual success depends on high performance by the team, which is unattainable without cooperation. Performance evaluation and reward systems that encourage cooperation are essential for improving performance. For example, companies can create cross-functional teams to develop new processes and reward team members on the basis of their collaboration and cooperation.

BCG’S VALUE-STREAM MAPPING 2.0

Companies have traditionally used value stream mapping to visualize their processes by individual activities, measure current levels of efficiency, and expose waste. The objective has been to make a process more efficient by reducing the number of steps.

BCG’s Value-Stream Mapping 2.0 (VSM 2.0) builds on this by seeking to understand the root causes of inefficiency and inadequate cooperation and gain insights into the process steps that lead to effectiveness and value creation. The objectives are to help companies promote value creation through greater cooperation, design a process that makes it happen, and establish enablers for sustaining the improvements.

To obtain an organization-wide perspective, VSM 2.0 requires the participation not only of process owners but also of internal customers and indirectly affected stakeholders. This broader participation enables a more comprehensive and detailed mapping of time and resource consumption throughout a process. A team can apply the approach, along with the tenets of Smart Simplicity, to identify behaviors that cause inefficiencies and quality issues. In doing so, the team can identify pain points and their root causes from the perspectives of both process owners and customers.

A company using VSM 2.0 first sets objectives for value creation and corresponding targets for KPIs and then designs or redesigns processes to achieve them. For example, a company may identify an opportunity to create value by improving its recruiting process and set a target for 80 percent of applicants to accept a job offer. Next, stakeholders from across the organization, including representatives of human resources, other support functions, and business units, would cooperate to develop improvement measures for the recruiting process that would allow the company to meet its target.

To embed improvements in the organization, the company sets clear responsibilities for process stakeholders, from end to end, and establishes accountability and incentives for an effective and efficient process. The implementation and maintenance of the improved process is continuously tracked. Companies can reward high performance through compensation, career development, and general recognition.

Promoting Improvements in Cost and Productivity

Companies using the X4X approach have captured significant savings rapidly within the first year as well as over the long term. As noted earlier, these companies have realized cost reductions of up to 35 percent in their support functions, and they have achieved cumulative productivity gains across the five dimensions of about 50 percent. Productivity gains in each of the five dimensions typically range from 5 to 10 percent, with the greatest potential arising from improvements in functional efficiency and costs and in end-to-end processes. Importantly, these productivity gains can be achieved without the need for major capital expenditures, which helps overcome executives’ reluctance to pursue structural changes and makes it more likely that positive returns will continue for many years after the project’s completion. Structural changes requiring capital expenditures, such as redesigning IT systems and outsourcing and offshoring, can generate productivity gains of about 15 percent.

For each dimension, companies have used a variety of improvements in specific functions to meet or even exceed project targets. One company’s experience illustrates the opportunities:

- Structures. By improving portfolio management within its human-resources function, the company reduced head count by 25 percent. Initiatives included implementing a global IT system, aligning meeting schedules, and developing standardized templates.

- Functional Efficiency and Costs. In the finance function, improvements to the forecasting process reduced the workload by 5 to 10 percent. Centralized forecasting and the elimination of duplicative bottom-up data gathering helped to implement the improvements.

- Leadership and Steering. In sales and marketing, the company simplified the management of product launches by defining quality gates to avoid last-minute changes and using frame contracts with external service providers.

- End-to-End Processes. The company reduced the workload of the strategy function by implementing clear governance processes. The organization also adopted standard formats for presentations to the board of directors.

- Individual Workplaces. In procurement, automation allowed the company to reduce the lead time for purchasing indirect materials (materials, such as cleaning supplies, that are used in the production process but that cannot be linked to a specific product) by up to 40 percent. For purchases costing less than €5,000, the company instituted an automated approval process to replace a long series of manual sign-offs.

The X4X approach also promotes greater levels of satisfaction with support services. The greatest improvements relate to internal customer satisfaction, which increases by 20 to 30 percent. External customer satisfaction increases by 5 to 10 percent, but the improvements can be significantly higher if business units are included in the improvement program as well as support functions. Employee satisfaction within support functions improves by 15 to 25 percent.

Results such as these create a virtuous cycle by helping to significantly increase the level of motivation among managers and employees—and to maintain it—which fosters continuous improvement in the future. Moreover, X4X tools, such as those that companies use to implement new daily routines, help to sustainably anchor cultural change and continuous improvement within the organization.

The X4X Approach in Action

Success stories are emerging from multiple industries. For example, a car manufacturer conducted a full-scale X4X program across each of the five dimensions for a select group of support functions. Reducing organizational layers and improving interfaces led to substantial structural improvements. The automaker also introduced daily routines for teams in the various support functions to help raise awareness of waste and establish a culture of continuous improvement. Additionally, the company trained more than 100 employees who would help lead a long-term cultural transformation and ensure the sustained implementation of the improvement measures. Combined, these measures allowed the automaker to reduce costs in support functions in scope by 12 to 15 percent. The company realized 80 percent of the savings by the end of the program’s first year.

As another example, an apparel manufacturer was burdened by inefficient and ineffective administrative functions, unclear responsibilities, and a lack of information about resource consumption. In contrast to the full-scale program conducted by the automaker, this company set up a modular program that focused on the bottom-up generation of improvement measures relating to end-to-end processes and individual workplaces and enabling the organization to sustain the improvements. The manufacturer set the target of increasing productivity by 15 percent and achieved this goal within the first year. It also successfully incorporated BCG’s lean framework into its corporate culture.

Determining the Starting Point

The X4X program is designed to be applicable to all industries and can deliver strong results in a full range of contexts. Instead of launching an entirely new program, companies can adapt X4X to incorporate previous or current efficiency programs, thereby allowing organizations not only to build on their achievements but also to promote the fast and successful completion of their projects.

To determine the starting point and make the case for action, companies should consider their responses to a series of questions, such as the following:

- Overall. How does our company’s performance compare with that of our peers, and are we prepared for intensified competition in our markets? Could our support functions create more value for the business? When we create new support services and processes, are we destroying value by increasing the complicatedness of our organization?

- Structures. Do we have unnecessary organizational layers? Are there opportunities to combine dispersed, but related, activities into shared service centers?

- Functional Efficiency and Costs. Can we further improve the service levels provided by the support functions? Is the organization burdened by duplicative services? Do we spend money on services that the business units do

not need? - Leadership and Steering. Have we established clear accountabilities in our support functions? Is the organization hierarchy within functions sufficiently “flat”? Have we set the right incentives for our managers?

- End-to-End Processes. Are the business units burdened by long waiting times for support services? Can our manual processes be automated? Have we reached a satisfactory level of standardization?

- Individual Workplaces. Are employees focusing on value-adding tasks? Can we reduce meeting times to allow for more productive work?

- Sustainability. Do we have approaches in place to ensure that improvements to support functions’ performance and our corporate culture can be sustained over the long term?

For many companies, the answers to questions such as these will point to opportunities to capture significant value by creating smart and simple support functions.