At the beginning of 2015, on the basis of fundamental measures such as household wealth and banking assets, Asia-Pacific represented about a third of the world economy and global finance. The asset management industry, however, has not kept pace. Asia-Pacific’s portion of global assets under management (AuM)—only about 15 percent—is unchanged since 2007.

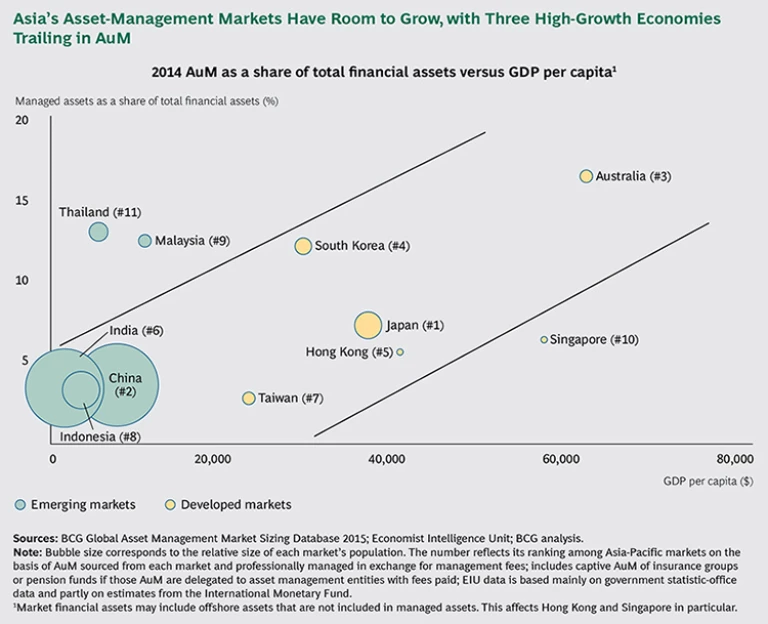

Judging by the numbers, a rebalancing of the global industry toward Asia is already overdue. And there is plenty of potential for more growth: three of the world’s most populous, high-growth economies are Asian markets that now rank lowest in AuM penetration. (See the exhibit below.)

Read more on this topic

Global Asset Management

- Sparking Growth with Go-to-Market Excellence

- The Asset Manager’s Go-to-Market Survival Guide

- Catching Asset Management’s Tilt Toward Asia

But are the conditions actually in place for Asia’s asset-management moment? What challenges will global managers face in riding the wave and expanding access as markets evolve?

BCG asked senior industry executives who collectively represent more than $1.5 trillion in regionally sourced AuM to explore these questions. Their responses reflect, foremost, that Asia-Pacific must be approached as a set of diverse markets.

- If managers get one Asia-Pacific market right, it must be China, the region’s second largest. The Chinese market is already larger than Australia’s and has grown to half the size of Japan’s, up from just one-quarter in 2007. For global managers, current means of market access to China’s domestic investors do not offer straightforward solutions. However, further opening of the market and the capital account are under way.

- Growth of the Asia-Pacific industry will increasingly be driven by wealth and retirement savings. Asia—particularly China—is on the verge of a shift toward retirement offerings. This is the result of the demographic wave of retirements, as well as upcoming pension reforms. In the near term, preferences for local products will challenge overseas-focused managers to decide how, when, and where to localize. At the same time, both local and foreign asset managers need to gear up to serve outbound flows from China and Japan into overseas asset classes.

- The wealth and retirement trends will drive more retail savings and investment. But this opportunity will also create a challenge because the retail fund business is widely seen as a failure in Asia, and this is exemplified by weakening investment in mutual funds. Managers in many Asia-Pacific markets fear that the retail business isn’t sustainable in its current form.

Virtually every manager wants to target high-net-worth segments because of the region’s expanding prosperity. Yet, so far, asset managers haven’t succeeded in capturing its wealth. Asia-Pacific, excluding Japan, overtook Europe in 2014 to become the world’s second-wealthiest region with $47 trillion. (See Global Wealth 2015: Winning the Growth Game , BCG report, June 2015.) With a projected $57 trillion in 2016, Asia-Pacific is expected to surpass North America (a projected $56 trillion) as the wealthiest region in the world.

Weighing Near-Term Concerns and Long-Term Growth

As the U.S. Federal Reserve prepares to tighten monetary conditions, Asia’s high-growth macroeconomic environment shares the stage with slowing economies and monetary easing. This raises near-term concerns about market volatility and outflows.

At the same time, the global growth trends toward passive strategies and fee compression in alternatives have been more muted in Asia-Pacific and other emerging markets. Market structures and discontinuities continue to offer greater opportunities for alpha generation than in more stable, mature environments. Many regional asset managers believe that a well-designed active-management platform remains the model best suited to meet regional demand.

The hunt for yield by investors in Japan and elsewhere in the region is supporting regionalization and globalization of investments. Some regional governments are pursuing policies and initiatives to put capital toward driving their economies, promoting growth of the asset management industry. This is particularly the case for China through its Stock Connect program, which opened Shanghai’s stock market to overseas investors, and through quota enlargements for the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) and Renminbi QFII programs. The mutual fund recognition between Hong Kong and China, scheduled for July 1, 2015, will open the door wider.

However, the industry’s growth will increasingly be driven by onshore wealth and retirement savings. Both regulators and investors will likely continue to prefer local vehicles for a high proportion of these assets, but there is a strong wave of support for local managers to develop their international asset-management capabilities to serve expected outbound investment flows.

Industry executives express strong support for local market development, but they are concerned by the possibility of financial protectionism. Asset managers that have traditionally focused on overseas fund vehicles, including Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities in the European Union, face a clear challenge: should they localize and if so, where and when? For China, the largest prize, the various and evolving means of market access offer no straightforward answers for global managers.

Regulatory inconsistencies—on issues such as client data migration, outsourcing, and localization of operations—are another source of concern. In a number of jurisdictions, it is becoming more difficult to centralize or regionalize middle- and back-office activities.

Industry executives would also like to see more action from regulators on product approvals, risk transparency, and suitability standards. One potential opportunity, many say, would be to receive speedier approvals in exchange for more homogenous product structures.

The Institutional Market Offers New Inroads

Institutional business in Asia remains a comparative bright spot. Asset owners’ desire to build their capabilities has had a positive impact for managers. While some asset owners are making efforts to internalize capabilities—particularly for direct investing and local asset classes—external managers have retained their value. They have broadened inroads in areas including asset allocation, portfolio construction, global diversification, risk, and talent management.

While large public and sovereign owners of assets are both still of prime importance, another tier of institutions is emerging in insurance and pensions. These institutions are the foundation for long-term industry growth. For nonlocal managers, however, they remain challenging and costly to serve due to their relatively smaller mandates, customized reporting requirements, and regional dispersion. Their emergence reinforces the need for client segmentation and tiering, as well as the need for specialized sales teams.

Asia-Pacific institutions continue to show strong demand for alternatives, particularly illiquid classes such as private equity, real estate, and infrastructure. From a yield and risk standpoint in the current fixed-income environment, they are seen as attractive substitutes. There is a growing interest in Asia-Pacific underlying assets, although the focus remains on North America and Europe. There are few, if any, signs of fee pressure on illiquid alternative asset classes: asset owners appear to recognize, in most cases, that they struggle to match the external managers’ expertise. On the passive end of the spectrum, a number of managers highlight increased interest in exchange-traded products from Asia-Pacific institutions as a means of managing short-term exposures.

Competing Visions for the Retail Fund Business

Asset managers continue to voice concerns about the attractiveness and sustainability of the retail fund business in many Asia-Pacific markets. Most observers agree that the current formula is not working. Retail investors remain accustomed to trading mutual funds as if they were individual stocks—as short-term speculative instruments rarely linked to an asset allocation or investment strategy. Knowing this, distributors persistently switch attention to newer fund offerings within a few months. The majority of new mutual funds experience a rapid short-term peak, followed by large-scale redemptions and permanent decline. Fee structures featuring high entry and exit charges for retail investors arguably reinforce these patterns. The overall result is that Asia-Pacific retail investors express little interest in mutual funds: the mutual fund share of household wealth has drifted downward for several years.

Optimists argue that there is a time lag effect: Asia-Pacific retail banks are investing heavily in upgrading wealth and advisory offerings targeted at affluent segments. Once these gain traction, a boost in demand for fund products should follow. To support this, a number of fund manufacturers have invested heavily in direct marketing—with both branding and investor education in mind—to encourage a shift toward solutions and outcome-oriented products, which offer broader exposures and, potentially, lower volatility in both performance and investor sentiment than do traditional funds.

However, according to the bear market case, current distributor and investor behavior poses intractable challenges for mutual funds. The industry’s future lies instead in life insurance and retirement: various large markets, particularly China, are reforming their pension systems and introducing defined-contribution components. This will, perhaps, be a longer, slower development and will require tax incentives for long-term investments that have yet to be put in place.

A Digital Future?

Despite a rush of interest in direct fund distribution, which is driven by the success of Chinese money-market funds linked to Internet giants, most asset managers anticipate limited disruption to their current intermediary relationships with banks and securities firms.

Few managers are keen to embrace direct-distribution models, citing the risk of harm to existing channel partners, lack of regulatory support, and additional complexity for on-boarding and servicing customers. However, there is perceptible interest in direct digital models that could serve as potential market-entry mechanisms, as well as a desire to adopt digital technologies to improve effectiveness. As in other regions, asset managers see significant potential to improve the customer experience by increasing connectivity, including creation of investor communities, providing portfolio analysis and education tools, and building demand-prediction functionality.

The Way Forward: Global-Local Partnerships

The outline of the industry’s Asia-Pacific future is already visible. Demographic and policy shifts will drive an expansion of onshore retirement markets, drawing a significant pool of regional savings into the asset management industry as a key source of global AuM rebalancing.

A broad range of local institutions and wealth intermediaries will emerge as key partners for global asset managers seeking expertise and diversification. But they will also demand delivery through local or regional platforms, and they will expect segment and channel specialization, requiring managers to invest more in sales functions. To meet these demands, local managers will need to build outward-looking alliances with global firms that go beyond existing domestically focused joint ventures.