Most banks have invested heavily in compliance over the last five years, in some cases doubling or even tripling their compliance budgets. At the same time, few institutions are truly satisfied with the returns on their investment in compliance. BCG’s clients have mentioned a “treadmill effect” of ongoing remediation, an uncoordinated patchwork of one-off enhancements, increased bureaucracy and complexity, and costs sometimes totaling 5 percent or more of the bank’s entire operating budget.

How can banks achieve better returns on their compliance investments? The answer is threefold:

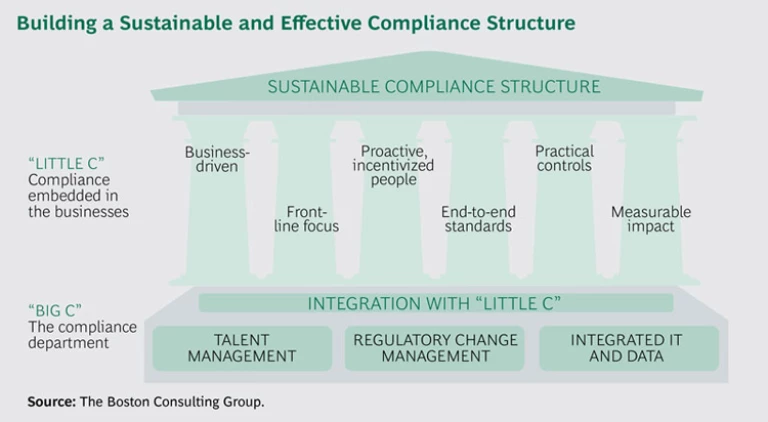

- Build the right foundation in the compliance department (“Big C”). Much of the recent investment in compliance has been reactive, addressing existing deficiencies or broad new mandates such as the Volcker Rule. Without proactive investment in the right base of capabilities, a compliance department cannot execute “Big C” compliance in a sustainable way.

- Embed compliance within the businesses (“little c”) and ensure that the necessary pillars are in place to sustain a culture of compliance. When “little c” is working well, compliance will be seamlessly built into the day-to-day activities and critical decisions of the bank.

- Create an effective interface between the compliance department and the businesses. This can require overcoming mutual mistrust, in addition to the tactical challenges of ensuring regular coordination—but it is the only way to ensure that compliance requirements are effectively (and efficiently) implemented.

Institutions that take these steps can achieve truly sustainable compliance. (See the exhibit, “Building a Sustainable and Effective Compliance Structure.”) They will be better able to comply with both existing and new regulations—and they will face less red tape. They will also be in a stronger position to take advantage of new business opportunities because they (and their regulators) can be confident that compliance risks are under control.

The Right Compliance Foundation

Despite the heavy investment in recent years, compliance departments often struggle with three critical building blocks of sustainability: talent, the ability to manage regulatory change, and IT infrastructure.

Attracting and Developing Talent. Strong “Big C” compliance requires the right mix of talent in the compliance department. While many institutions have succeeded in identifying regulatory experts, they have often struggled with other critical roles, such as project management, reporting, training, and communications, thus creating weaknesses in the compliance program. In many cases, adding talent from within a bank’s business or IT areas can fill capability gaps while strengthening the compliance department’s understanding of the rest of the bank.

Attracting the right talent requires a clear value proposition—either a well-defined path for advancement within the compliance department or the prospect of returning to the business, or both. A credible, successful talent-development program can demonstrate to high-potential candidates that compliance is a viable career path. The same talent-development program can create a path for retaining and developing existing talent, filling managerial roles, and preventing poaching of critical staff. Successful institutions proactively examine and address talent gaps not just in terms of compensation but also in terms of work environment and culture.

Developing a Strong Regulatory Management Capability. “Big C” compliance involves managing several types of regulatory change. These include broad new regulations (such as the Volcker Rule or Dodd-Frank); new but more targeted regulations; changes in existing regulation; and, crucially, changes in regulatory interpretation and regulator expectations. Managing regulatory change requires developing good policies, implementing them effectively, and addressing the impacts of change. If regulatory change is managed poorly, an institution can face remediation, leadership distraction, or both.

Many institutions struggle to develop policy effectively. In some cases, they create detailed policies at the corporate level that are deeply prescriptive about how a regulation must be implemented (“policy-dures”). However, these details often fail to account for the processes, systems, and products of all of an institution’s businesses everywhere it operates. For example, one institution unintentionally prohibited underwriting and treasury operations when it reworked its new-product policy—and prohibited the bank from taking any financial positions that were counter to its customers’ positions. In other cases, policies are too vague and fail to clarify which activities and practices are allowed.

Unsustainable policies foster an environment in which noncompliance is tolerated as a way to make business more efficient. To write better policies, institutions need an effective comment process that ensures business input and clear guidelines about the right level of detail to provide at the corporate level—and establishes where business and legal entity–specific adjustments are required.

Even if policy development is managed well, execution is sometimes not. In addition to effective implementation of new policies, the collective portfolio of all regulatory and policy implementation requires coordination across the institution and rigorous program management to ensure success. Both the central program-management office and each specific area must be given adequate resources, and resource needs should be actively managed and prioritized. Institutions that do not manage the impacts of change or provide adequate resources will suffer the effects of distraction and potentially paralyze a bank’s businesses. At one bank, for example, middle managers who were not part of the compliance department were required to spend more than 20 hours per month in meetings related to regulatory change implementation.

In addition to having a solid policy framework, institutions should proactively examine their product and service offerings in light of the changing regulatory environment. Such reviews should lead to thoughtful decisions about how products should be structured and marketed and even whether they should continue to be offered, especially in the case of the riskiest products.

Investing in the Right IT and Data Infrastructure. Many banks are saddled with legacy compliance IT systems that were built piecemeal and are no longer able to meet current needs. In the worst cases, these systems or the versions in use are no longer supported by the original vendor, or are supported by the funding of a single institution. One institution had to pay more than $2 million a year to continue operating a legacy anti-money-laundering system, even though the vendor was no longer making improvements. In such cases, manual workarounds proliferate and large numbers of both “Big C” and “little c” FTEs are required simply in order to do basic reporting. Correcting this situation requires the right investments and a strong partnership with IT to ensure that systems can capture all requirements without being overdesigned.

Many institutions have also overinvested in scope in their compliance IT systems. For example, one institution built a know-your-customer (KYC) system with 190 fields, far more than were ever likely to be required even for institutional customers. By focusing on true compliance requirements, one BCG client was able to eliminate 30 percent of the cost of its most important systems project.

Strengthening Compliance in the Business

While “Big C”—a strong compliance department—is critically important as a second line of defense, the day-to-day compliance of an institution is determined by “little c,” or the way compliance is executed in the businesses, which is the first line of defense. If a business does not build compliance into the way it works, no amount of “Big C” investment will overcome risk. There are six capabilities or pillars required for embedding compliance in the businesses.

Business (P&L) owners need to take responsibility for compliance. Many business leaders assume that compliance is something that needs to be handled by experts. In reality, leadership from business managers is what makes compliance happen. Business leaders need to understand the risks associated with their business and take ownership of and proactively manage those risks. The most effective business leaders chair their area’s compliance committee and use that forum to discuss not only potential compliance risk in the business but also team performance in identifying and mitigating issues effectively. They make compliance an integral part of key business decisions, such as launching new products. Furthermore, they make staff feel comfortable about raising compliance concerns and having frank discussions about issues, including compliance objectives and processes. If a business’s culture does not support open discussion, risks will remain hidden.

Focusing on the front line is critical. In our experience, the people who can make compliance happen are often front-line staff. In call centers, for example, representatives need to understand potential compliance issues that affect how they can market products or what they are able to promise to customers. In the case of commercial banking and wealth management, bankers might unwittingly commit a compliance violation at a customer’s request (for example, by removing critical information from SWIFT messages). Training and education are important for preventing costly violations of customer protection laws or sanctions. For a training program to be considered effective, all of an institution’s employees, as well as its contractors and affiliates, should understand the regulations that apply to their jobs—and what is and is not permissible.

Rather than waiting for outside evaluators to detect issues, leading banks test their own operations. One bank, for instance, proactively set up testing for its mortgage operations. It conducted the testing anonymously, using techniques similar to mystery shopping, and found out where personnel were performing well and where further training and support were needed. From a reputational and cost management point of view, the approach proved more effective than waiting for regulators—or even internal auditors—to find deficiencies. How often and closely a bank tests a business, function, or vendor depends on its risk exposure.

A risk-conscious culture requires the right incentives and controls. All employees must be aware, equipped, and motivated to appropriately weigh the risks and rewards of their actions, including the risk of noncompliance. This requires changing the work environment that employees are operating in (including decision rights, key performance indicators, compensation, and nonmonetary incentives) and rewarding prevention. Top-down value statements are not enough. Instead, there must be systematic incentives, especially when the nature of compensation could favor noncompliance (such as in sales roles)—backed by sophisticated and rigorous controls and monitoring, and clear accountability and consequences for improper actions. In addition, the bank’s culture and informal incentives must be aligned against noncompliance. If leaders who do not pay attention to compliance are promoted or otherwise rewarded (for example, with sales or innovation awards), a culture of noncompliance will proliferate.

Compliance and conduct standards must be applied end-to-end. A product’s structure and pricing, how the product is marketed, distributed, and serviced, and the back office processes and IT that support the product must all be designed with compliance in mind. The lack of an end-to-end view can lead to unintended consequences. One U.S. state, for instance, requires that products be serviced in all languages in which they are marketed, which means that the publication of a simple marketing brochure can unintentionally create new service obligations in call center operations.

Controls should be effective and practical. Controls must be meaningful and practical—certainly more than just a “check the box” exercise. They should also not place an unrealistic burden on the business. One compliance department, for instance, designed a customer risk assessment for all new customers that would have taken more than an hour to administer to a retail customer. The bank’s systems could not support all the fields in the assessment, and the front-line staff could not complete the full survey owing to time constraints. A more practical approach is to involve end users in the design of controls, making sure that any new controls are implementable. For instance, understanding how quickly customers will abandon a new account opening can provide a natural time limit for how quickly KYC data can be collected. Front-line employees and managers often have good suggestions about how to make such processes faster and more effective.

The impact of “little c” compliance within the businesses should be measurable. A successful compliance program should exhibit good quality control (that is, all regulatory requirements in a process are accounted for), low levels of complaints, and short backlogs in key processes such as ongoing KYC recertification. Business and compliance staff should jointly identify a set of metrics focused on outcomes (such as meeting all KYC standards) rather than on tasks (such as having 95 percent of line staff complete compliance training)—and they should monitor these metrics in order to spot potential issues. Such metrics should be used to drive a culture of transparency, one in which the impact and status of the metrics are routinely shared.

Getting the Right Interface Between “Big C” and “little c”

In many institutions, the relationship between the compliance department and the businesses is one of mutual suspicion at best. To make this crucial interface effective, the compliance department needs to give clear input at the right time during business processes (for example, in the product development phase). By the same token, the businesses need to flag potential compliance issues early and ensure that the compliance department has full information in order to be able to provide effective input. Both sides should have an ongoing dialogue about how to make their interaction more effective. The best way to do this is to ensure regular coordination, both on existing issues and on new ones. A good example is an institution that successfully redesigned its product approval process using a joint team of compliance and business leaders. The result was a process that improved speed-to-market yet was recognized as best-in-class by regulators. These types of win-win solutions epitomize how “Big C” and “little c” can work in concert to integrate compliance successfully into the businesses.

Most financial institutions will continue to invest heavily in compliance in the coming years. By building the right “Big C” compliance foundation, putting the necessary “little c” pillars in place in the businesses, and getting the right interface between “Big C” and “little c,” institutions can achieve superior returns on their compliance investment—and have greater confidence in their ability to innovate and take business risks safely. We believe that strong, sustainable compliance will be a key source of competitive advantage for financial institutions over the next five years, providing significant rewards to institutions that invest and implement intelligently.