The intensifying competition between rising emerging-market companies and established multinationals remains at the top of the agenda for CEOs. Challengers not only are radically disrupting a wide range of industries but also are increasingly becoming global leaders themselves. This article is part of a new report, Dueling with Dragons 2.0: The Next Phase of Global Competition, that analyzes the sea change under way in the global automotive-supply, construction-equipment, and chemical industries and the implications for both multinational corporations (MNCs) and emerging-market players (EMPs). The report, along with its recommendations, is based on comprehensive quantitative and qualitative research that included interviews with more than 100 executives and industry experts in China, India, and Latin America.

We found that even though the nature and competitive landscape of these three businesses vary significantly, MNCs in each industry are facing urgent challenges to their leadership from EMPs. Key executives from both MNCs and EMPs expect that competition will further intensify in all three industries. Improving global competitiveness, therefore, must be a top priority of CEOs.

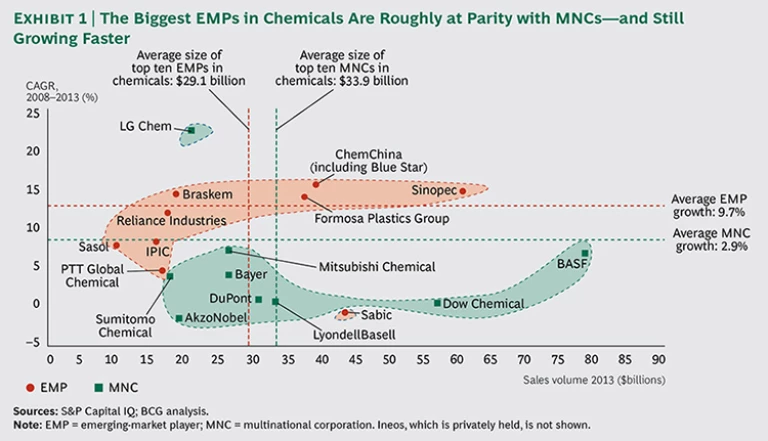

The fact that leading MNCs and EMPs in the global chemical business are roughly at parity in terms of revenues illustrates the advanced stage of global competition in this industry.

The Current Landscape: The Fight for Global Leadership

As in the automotive-supply and construction equipment industries, global demand for chemicals is shifting to emerging markets, which now represent roughly half of the $5 trillion market worldwide. Major MNCs in chemicals have considerable local production in emerging markets and have known these economies well for decades. However, the balance of power has now shifted: several EMPs—most of them with close ties to national oil companies—have become global leaders. (See Exhibit 1.) With $60 billion in revenues in 2013, for example, China’s Sinopec is larger than Dow Chemical. Sabic, a $50 billion conglomerate based in Saudi Arabia, is bigger than LyondellBasell Industries, DuPont, and Mitsubishi Chemical. The sheer numbers obscure big differences among market segments, however. As of now, EMPs dominate base chemicals and basic plastics, and incumbent MNCs generally are stronger in specialty chemicals, industrial gases, agrochemicals, and fertilizers.

EMPs have also become more aggressive in mergers and acquisitions on a global basis. From 2007 through 2012, the amount that EMPs spent on such acquisitions grew from $7.9 billion to $10.6 billion. The transaction volumes of MNC acquisitions of emerging-market-based chemical companies dropped from $4.6 billion to $2.8 billion during that same period. EMPs are making bigger deals, too. The average EMP outbound acquisition—$881 million—was nearly nine times larger than the average outbound MNC deal.

The Future Landscape: The Battle Moves to Specialty Chemicals

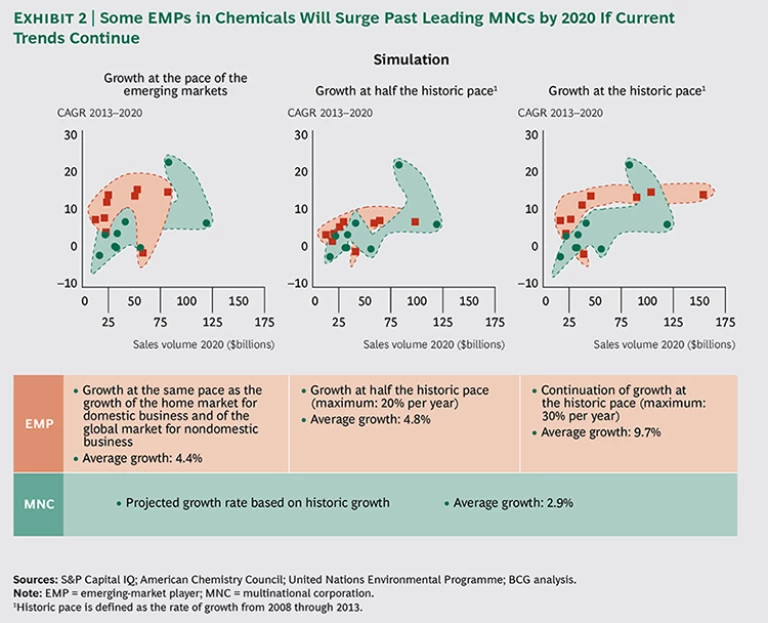

Global demand trends are likely to continue to favor EMPs, especially those based in Asia. By 2020, the Asia-Pacific region is projected to account for approximately 53 percent of global sales of chemicals. The shares of North America and Western Europe are projected to shrink to 21 percent and 15 percent, respectively, by 2020.

It is no surprise, then, that if EMPs manage to maintain a certain degree of growth, they will soon exceed MNCs in size. (See Exhibit 2.) Based on our interviews, we also expect EMPs to further expand into specialty chemicals—not only because they are more profitable but also because these companies want a large share of the fast-growing local market for such chemicals. China identified new materials as one of the key strategic areas on which to focus in the twelfth five-year plan, for example, meaning that the government will support additional efforts in areas such as specialty materials, advanced polymers, inorganic materials, and composites.

Winning Globally in the Chemical Industry

Largely because MNCs and EMPs are roughly at parity in terms of size, the executives we interviewed from both types of companies in the chemical industry perceived a similar set of urgent challenges. Their highest priorities, however, depend on the industry segments in which they compete.

Products and Technology. The following strategies were cited prominently by executives:

- Diversify into higher-margin products. Executives from both MNCs and EMPs stressed the need to develop their product portfolios so that they can earn higher returns. Executives from MNCs see the need to constantly adapt their portfolios and generate new business opportunities. In part, that will require developing ever more customized solutions for their clients. EMP executives, not surprisingly, still see large white space for their companies in the realm of specialty chemicals. They highlighted the need to add more value for customers in their existing businesses rather than enter completely new product areas. One example of such a premium product is Zetag, a polymer developed by BASF that more effectively de-waters sludge, reducing the cost of disposal for the customer.

- Create products tailored to local markets. Makers of specialty and base chemicals alike said that their biggest challenge is to create products that are better adapted to local markets. When creating tailored, local products, it is important to keep in mind that there are several ways of doing so. Both MNCs and EMPs should systematically follow three strategies: proprietary product development, licensing of technology in exchange for market access, and acquisition. In any given segment, a combination of these strategies may become appropriate, but experts expect that licensing and acquisition will gain in relevance. Dow Chemical is showcasing these strategies in its electronics chemicals segment, for example. Through its own R&D, Dow brought Silveron, a sustainable surface-finishing solution that avoids cyanides, nickel, and lead, to market in 2014. At around the same time, Dow entered into a licensing agreement with Nanoco Group for the exclusive worldwide sale and manufacturing of cadmium-free quantum dots (Trevista), which allow for better color in electronic displays. What’s more, Dow acquired Lightscape Materials in 2012, adding phosphor technology to its existing LEDs and improving the quality and color output of displays.

Operations. The following priorities emerged in our interviews:

- Localize R&D and management. Although a local R&D presence is necessary to be close to the customer, it is no longer a real differentiator. Eight of the top ten MNCs in the chemical industry have at least one research center in the Asia-Pacific region. For example, at its Shanghai R&D campus, BASF develops new products tailored to the needs of its emerging-market customers. Being closer to customers sometimes requires fundamental adaptations of an organization’s management structure. In a globalized industry such as chemicals, this can even mean relocating the global center of a business unit, including functions responsible for key strategic decisions and profit and loss, in its most important market. (See “BASF: Staying on Top by Going Local.”)

BASF STAYING ON TOP BY GOING LOCAL

BASF is the world’s largest chemical company, with approximately $93 billion in sales in 2014 and more than 112,000 employees. As such, one of the biggest challenges it faces is to maintain growth amid intensifying competition from emerging-market-based companies. BASF has thus decided to take competition into emerging markets and invest heavily in localization.

In 2012, the company opened its BASF Innovation Campus Asia-Pacific in Shanghai to further its goal of building a strong R&D network connecting various BASF sites and universities in China, Japan, South Korea, and other Asian markets. The company aims to have approximately 25 percent of its global R&D workforce in the Asia-Pacific region by 2020. It even manages several global businesses from a base in emerging markets. For example, the company moved the global headquarters of its dispersions and pigments division to Hong Kong in 2012. The division head and 50 global positions were transferred to Hong Kong from Germany and Switzerland. The move allowed BASF to have a better view of its key customers and markets in Asia, which already accounts for a significant part of the division’s sales and will be crucial if the company is to remain a global leader.

- Lower cost and secure feedstock. Cutting cost is a particularly important priority for basic-chemical producers. Because the majority of production processes for bulk base chemicals such as ethylene are well understood, there is limited room for players in this segment to make breakthroughs on cost. Of course, large cost-optimization programs that target operational effectiveness at plants can solve a piece of this puzzle. But experts agree that securing cost-competitive supplies of feedstocks is essential. As the chemical industry grows, so will demand for feedstock. But reserves of major feedstocks—such as natural gas, coal, and oil—are not distributed evenly across the globe. Both MNCs and EMPs, therefore, are looking to secure access by forming partnerships or even buying assets, such as palm oil or sugarcane plantations. Sadara Chemical is one of the most prominent examples of a joint venture between an MNC and an EMP to tap the world’s largest oil reserves. (See “Saudi Aramco: Leveraging Saudi Resources to Become a Chemical Giant.”)

SAUDI ARAMCO LEVERAGING SAUDI RESOURCES TO BECOME A CHEMICAL GIANT

Although Saudi Arabian Oil, known as Saudi Aramco, has long been one of the world’s biggest suppliers of petroleum and gas, it has only recently ventured into the petrochemical industry. Together with Dow Chemical, the company has created Sadara Chemical, which is likely to put Saudi Aramco on the global map.

Sadara, 65 percent of which is owned by Saudi Aramco, is building the world’s largest chemical complex ever constructed in a single phase. When it is completely up and running in 2016, the $20 billion complex will include 26 world-class, integrated manufacturing plants with a combined capacity of more than 3 million metric tons of high-grade plastics and specialty chemicals. Nearly half of the complex’s output is expected to be shipped to fast-growing Asian markets. The Middle East and Europe will also be key destinations.

Sadara illustrates two key trends in the chemical industry. The first is the push of emerging-market players to own larger parts of the chemical value chain. The second is the growing importance of partnerships as potential game changers in this asset-heavy industry.

Go-to-Market Approach. In our interviews, executives emphasized the following key strategies:

- Increase the focus on the environment. Executives we interviewed from both MNCs and EMPs are greatly concerned about sustainability. They brought up the importance of complying with local environmental regulations in multiple interviews. Chemical producers should do more than comply with regulations, however. Executives believe that green processes can be a true source of differentiation. Lenzing, a producer of viscose fibers, provides a good example. When Chinese competitors took 55 percent of the global viscose market in 2010, Western companies including Acordis, Kemira, and Svenska Rayon had to close production sites. Lenzing remained in business, realizing that it is regarded as a world leader in environmentally friendly and efficient viscose production. A sustainable production process based on 100 percent natural beech wood appealed to customers that were focusing on green approaches and were willing to pay higher prices for such products.

- Maintain reliable global quality standards. A consistent global offering is an enabler of competitive advantage and an effective way to protect and broaden the customer base—especially in highly specialized chemical applications. When customers are global and require that their suppliers serve them globally, the ability to provide consistent quality everywhere in the world can create a competitive advantage that is not easy to copy. In fragrances, for example, the ability to produce exactly the same quality everywhere in the world is a requirement for staying on a list of core suppliers. And constant adaptation to regulatory changes in all countries, such as prohibitions against natural essences that cause allergies, is absolutely necessary and can be a means of differentiation.

Who will win in the chemical industry—the MNCs or the EMPs? Most experts and executives agree that this is the wrong question. There will be successful players from both camps. Rather, executives need to ask themselves: what do I need to do so that my company is among the winners?

Winning the Next Phase of Global Competition

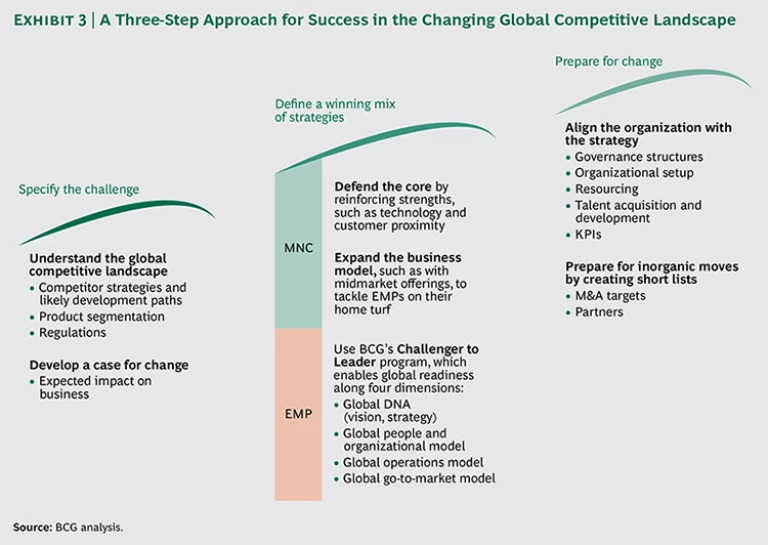

As a result of our extensive work with leading companies on their globalization strategies and the findings from this study, we have defined a three-step approach for companies to succeed in the quickly changing global competitive landscape. (See Exhibit 3.)

Step One: Specify the Challenge. Most companies today take stock of market developments and key competitors in their regular strategy and planning processes. We have found, however, that these standard processes often fall short of establishing a commonly shared opinion when it comes to the opportunities and risks of globalization. Also, the remarkable speed with which new competitors from emerging markets have arrived on the scene requires companies to maintain extensive intelligence on their competition. Many organizations have found it useful to track in detail the development of their top 20 or so competitors regarding major wins, investments, partnerships, and geographic footprints.

Given the sometimes volatile and difficult-to-forecast developments in global markets, it is very important to form a common vision of what the industry will look like in three to five years. This requires an understanding of the areas for action. What are the fundamental trends in demand, for example, regardless of economic or political turmoil in some countries? How does a company compare with its competitors? What will be the next breakthrough in technology? How are regulations likely to change? This vision should guide efforts in the second step of the process and the big bets a company takes.

Step Two: Define a Winning Mix of Strategies. In this article, we have outlined the most common areas requiring action by MNCs and EMPs in the chemical industry.

At the most basic level, MNCs must first defend the core—their home markets and the global premium segment—by reinforcing strengths such as technology and customer proximity. Second, they must expand their business model to tackle EMPs on their home turf. Because we believe it is helpful to think about both targets from three angles—products and technologies, operations, and the go-to-market approach—we have offered our analysis from those perspectives.

Depending on the industry and the specific position of a company within it, the relative importance of these three levers varies greatly. We strongly recommend taking a holistic view, because many companies find that they need to undergo a transformative approach that comprises a wide range of diagnostics and change measures in all three categories to address their globalization challenge.

EMPs typically enjoy the benefits of a relatively low cost position and a growing home market. However, it has been our experience that during the phase of hypergrowth, many EMPs are not able to build the organizational and technological capabilities that they need to continue their global expansion. On the basis of our broad experience in working with emerging-market challengers, we have defined a dedicated, comprehensive approach that enables an EMP to go global. The global Challenger to Leader Program covers four areas and ensures that they are aligned with the c ompany’s globalization agenda:

- Global DNA: vision, culture, and master strategy

- Global People and Organization: leadership, talent management, organization, and governance

- Global Go-to-Market Model: product strategy, sales approach, partnerships, and stakeholder management

- Global Operations: global footprint, innovation, and operations model

Step Three: Prepare for Change. We see two key enablers of a successful globally competitive strategy. One is to properly align organization and governance structures. Adjusting key performance indicators and defining the right balance of decision authority between headquarters and country operations are two important issues that must be resolved.

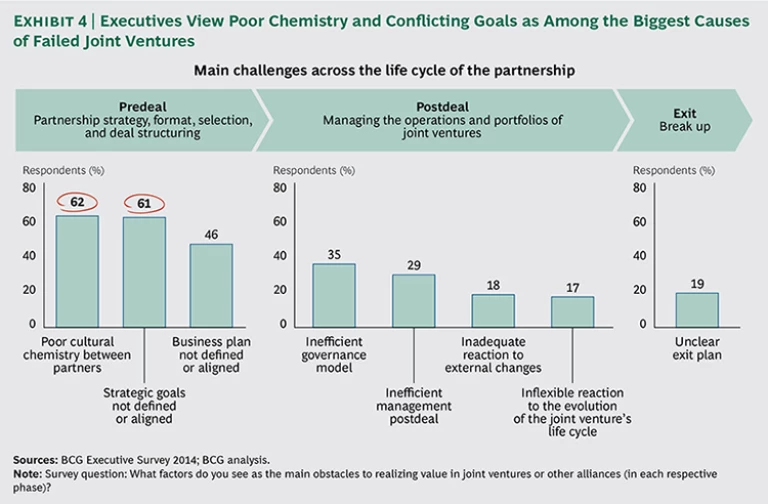

The other key enabler centers on partnerships and joint ventures, which many companies will find are key elements in their strategy mix. A recent BCG study on mergers and acquisitions revealed that the vast majority of executives are disappointed by the performance of their cross-border joint ventures. (See Getting More Value from Joint Ventures, BCG Focus, December 2014). The analysis identified several critical measures that can help avoid such disappointment. (See Exhibit 4.) They include ensuring that there is cultural chemistry between partners and that there is alignment on strategic goals and business plans, including a clear process for when business plans are not met along the way. Other measures are a sound governance model and an exit plan.

Globalization will continue to bring significant shifts to the chemical industry—and undoubtedly to many more. But despite these shifts, most of the executives we surveyed agreed that for the well-prepared company—whether from the developed or the developing world—the globalized market offers much more opportunity than risk.