From a business perspective, Africa is at an inflection point. Local African companies have made investments and have expanded their offerings, in many cases taking business away from multinational incumbents. The multinationals are rethinking their positions on the continent and contemplating additional investments of their own. There’s a little bit of a chess match going on, as both sets of players look into the future and try to figure out which strategies to pursue.

Even now, as low oil prices threaten the continent’s energy exports, Africa’s long-term positives are too big to overlook. Population growth and higher household incomes have helped lift Africa’s GDP by more than 5% a year on average for the past 15 years. In addition, the Africa of today is more politically stable, with over half the 54 countries on the continent now holding democratic elections, compared with fewer than ten in 1990. As a result, foreign companies and governments have dramatically boosted their investments in certain parts of the continent: foreign direct investment in sub-Saharan Africa increased by a factor of five from 2001 to 2012.

Demographics are also working in Africa’s favor. The continent has a sizable working-age population; within a few decades the proportion of Africans in the workforce will exceed that of Europeans and Asians in their respective regions, according to the United Nations. People across Africa are also more educated and more connected to information sources than ever, with mobile phone and Internet use growing rapidly.

Together, those changes have put many African countries on a more solid economic footing, allowing them to withstand shocks that once might have been devastating. In 2014 and 2015, for instance, Africa as a whole maintained economic growth above the world average despite the oil price decline, the outbreak of Ebola, and high-profile attacks by militant groups such as Boko Haram and Al Shabaab. Low oil prices have pushed several African countries to the brink of recession and have significantly slowed the continent’s growth. But Africa overall is holding up much better than it has in the past, and the hope is that the slowdown will be temporary.

As Africa’s economy has risen in recent years, so have valuations, making it more expensive for MNCs to do business on the continent and to acquire companies based there. Still, the higher cost of entry hasn’t diminished foreign interest. An analysis by The Boston Consulting Group found that almost nine in ten MNC CEOs visited the continent in 2013, compared with fewer than one in ten in 2000. To many of those executives, Africa remains a frontier with huge opportunity for growth but unfamiliar rules. It’s still early in the game, and both the MNCs and the Africa-based companies they’re competing against have opportunities to develop dominant positions.

MNCs in Africa Are Growing—but Not Winning

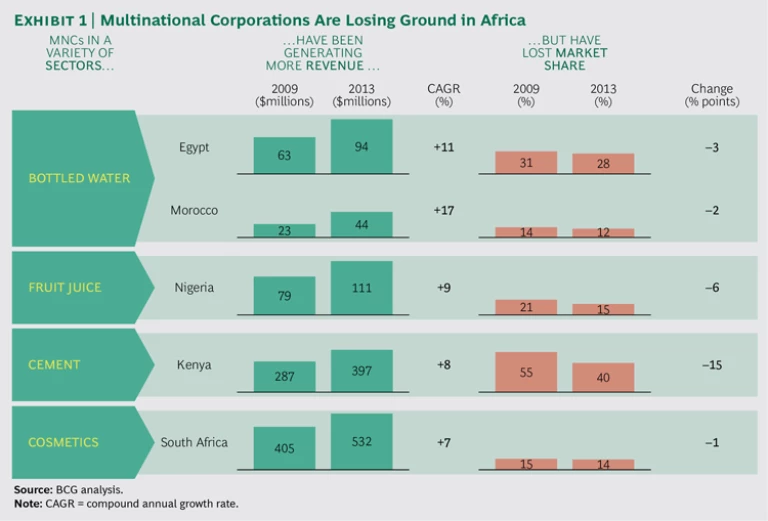

For most MNCs, early results in Africa have been mixed at best. It’s true—European and North American companies in a variety of industries are earning a higher percentage of their global revenue on the continent than they ever have. But the numbers are still small. And by another, perhaps more telling, measure—African market share—many of those companies are going backward. (See Exhibit 1.)

What MNCs are facing in Africa is similar to what they’ve faced in parts of Asia and Latin America: an increasingly capable set of local competitors. In a 2013 BCG survey of executives in developed markets, 73% said they considered local companies in emerging markets to be a threat. In contrast, 50% said this about emerging-market-based MNCs, and 40% said this about MNCs in their home markets. The entity looking to eat your lunch in Africa is one that your board of directors—and maybe you yourself—didn’t know existed until recently.

“There are simply too many attractive market opportunities around the globe,” a survey respondent observed. “MNCs are therefore spreading themselves thinner, while locals for the most part are very focused.”

The Rise of the African Lions

We used the term African Lions to describe the eight African countries with per-capita incomes that several years ago exceeded those of the so-called BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China). (See The African Challengers: Global Competitors Emerge from the Overlooked Continent , BCG Focus, May 2010.) African Lions is an equally apt description of the many Africa-based companies standing in the way of MNCs from Cape to Cairo.

Some of the Lions are pioneers that beat MNCs into African markets and have all the advantages of incumbents, including a huge market-share lead and broad name recognition. The South Africa–based mobile telecommunications company MTN, which made a bold move into Nigeria when Western carriers were holding back, is an example. Another is the cosmetics company Biopharma Laboratories, which is especially strong in Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire and through deft early moves has increased the cost of entry for international rivals in several other African nations. The Moroccan banks Attijariwafa, BMCE, and Banque Populaire are further examples of African companies that are leading the market. They continue to beat international banks at home and have quickly expanded across French-speaking Africa.

Other African Lions have entered terrain already trod by MNCs and have either slowed the progress of those rivals or turned the momentum decisively in their own favor. One challenger that has succeeded in this way is Bidco, a food company that has grabbed a majority share of the edible oils segment in Kenya. Another, Mombasa Cement, began manufacturing in Kenya in 2009 and has altered the competitive dynamics of that market. And Refriango, which introduced Blue, its top soda brand, in 2005, is now the uncontested soft-drink leader in its home market of Angola.

The Lions (many of them with founders of African lineage, others with family histories in countries in other regions, such as Lebanon, France, and India) are benefiting from a leveling of the playing field in areas where MNCs once had an advantage. As debt and equity have become more available to African companies, the gap in capital access has narrowed. Likewise, a decade or two ago, businesses on the continent couldn’t hope to compete with MNCs when it came to technology and know-how. Today, however, African companies have the option of buying expertise in the global engineering market and of partnering with Chinese and Indian service providers. Moreover, highly skilled Africans have been returning to their homelands. Students in countries such as Nigeria, Kenya, and Morocco still emigrate, but nowadays they’re more likely to come back after they’ve gotten their educations.

Yet another long-standing disadvantage of African companies—their small scale relative to MNCs—has also diminished as more African companies have grown in their home markets and have expanded to other parts of the continent. With the exception of a few technology sectors, such as consumer electronics and microelectronics, scale is no longer an advantage strictly of the foreign companies operating in Africa.

In addition to benefiting from an improved economic and political environment, successful African companies have ways of doing business and an adaptive nature that can give them an edge in Africa’s complex environment. Indeed, those are their biggest advantages. If MNCs want to improve their competitive positions, they must do what successful businesses always do: break down the strengths and weaknesses of the competition. It’s like the boxer who understands that his best chance of success lies not in going into the ring and doing what he has always done but in studying—and adapting to—the tactics of his adversary.

The Roots of the Lions’ Advantages

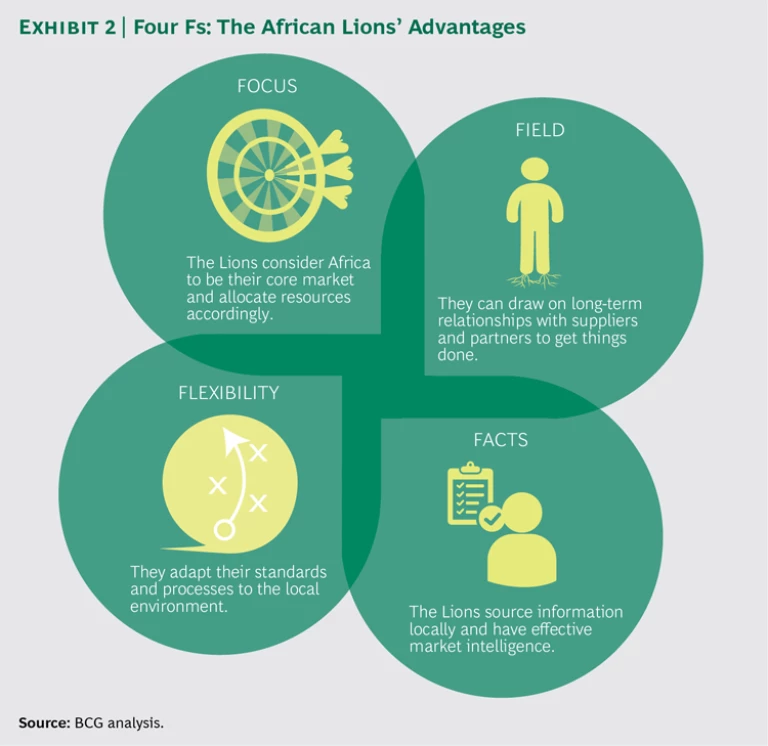

In deconstructing the African Lions’ edge, four factors stand out: their commitment to local markets (Africa is the Lions’ top priority and often the only place they operate), their extensive on-the-ground experience and proximity to decision makers, their superior grasp of information relevant to local markets, and their comfort with informal business environments. Put another way, successful African companies have the advantages of focus, field, facts, and flexibility. These are the four Fs of the African Lions. (See Exhibit 2.)

Focus. If you put two football teams on a field—one that must win in order to stay in a tournament and another that is already assured a position and is favored to win it all—the team that has more at stake will probably make the greater effort, and the players will play the match of their lives.

That explains the first point in the African Lions’ favor. With the overwhelming majority of their revenue coming from Africa, local companies have nothing to fall back on. If the business fails at home, it fails altogether. As a result, African companies put everything they’ve got into growing their market shares on the continent. When the Nigerian government made local production a condition of getting certain kinds of import licenses, Dangote Cement, based in Lagos, went all in, adding plants capable of producing 18.5 million tons of cement annually. In contrast, the biggest international cement company in Nigeria added only 5 million tons of annual production capacity. Partly as a result, Dangote has muscled aside its more experienced MNC rival to grab a dominant share of Nigeria’s cement market. The company is now expanding to other parts of Africa.

Similarly, in the past few years, as Western banks held back, the Moroccan insurer Saham Group went on a buying spree on the continent, picking up insurers in Angola, Kenya, Rwanda, and Nigeria. The insurance market in most parts of Africa is nascent, but African consumers plan to increase their spending substantially on insurance products, according to a 2013 BCG survey. As that happens, Saham will be well positioned to compete.

Focus also means developing products specifically for African markets. The beverage company Chi has picked up significant share in Nigeria, at the expense of some major MNCs, through a product line that appeals to Nigerians’ national identity (“Be Nigerian, Buy Nigerian,” as one of the company’s marketing campaigns puts it) and caters to their growing preference for healthful fruit drinks.

MNCs often can’t justify the cost of developing new products for African markets and so may try to compete with offerings made for Westerners. What’s more, MNCs frequently reallocate their investment capital, weighing one geographic region against another. An emerging economy like Africa, for a variety of reasons and in a given year, could become less of a priority and face cuts that would affect such areas as marketing, distribution, and customer service. MNCs in Africa have not pulled back significantly, but as challenges keep arising on the continent, they are sometimes hesitant to move forward. This cautious approach makes the African Lions’ focus, by comparison, even more powerful.

Field. In emerging markets, there is no substitute for on-the-ground experience. That is certainly true in Africa, which comprises dozens of countries, thousands of languages, and distribution channels that vary sharply by region. In many parts

of the continent, success depends on strong personal relationships, and verbal agreements are often more important than written contracts. Someone who understands that—who has a feel for and a genuine interest in local practices and cultures—has an advantage.

Local African companies are generally superior in this regard. Their top executives have often been in their roles for 20 years or more, and their managers are on a first-name basis with everyone in their ecosystem. In contrast, most CEOs of MNC subsidiaries in Africa are expatriates, typically on a three-year rotation. The success in Africa of some European, East Asian, and Middle Eastern family businesses, whose management teams have lived and worked on the continent for decades, proves that it isn’t necessary to be African by nationality or lineage to have the advantages of on-the-ground experience. What matters is the accumulated time spent in a market and an executive’s ability to understand its dynamics.

The Lions’ degree of integration in their local ecosystems has helped them move to new parts of the value chain and thus capture a lot of ground from MNCs. In the past, local companies were positioned either upstream, thanks to their access to raw materials, or downstream, owing to their proximity to end users. MNCs were

almost always in the middle of the value chain, where end products are manufactured and where scale and industrial know-how are the major sources of competitive advantage.

Now, local companies that had been operating strictly as suppliers or distributors are taking advantage of their powerful ecosystems to move into manufacturing. In doing so, they are chipping away at what was once a bulwark for MNCs—their superiority in manufacturing and their domination of the value chain’s so-called transformation front.

The dairy company Copag in Morocco, for example, has won market share from MNCs in that country by expanding beyond distribution into manufacturing. Copag now makes cheese and yogurt—moves made possible by the company’s strong connections to producers of raw milk, including a network of six dozen Moroccan milk cooperatives.

Dangote Cement has also moved into manufacturing. After initially doing only transport and distribution, the company is now making its own cement. That move, along with the decision to substantially increase capacity, has allowed Dangote to leapfrog its main international rival in Nigeria.

Facts. To executives in Western companies used to reliable data, Africa can come as a bit of a shock. A European or North American executive assuming a new post as a country or regional manager in Africa might be handed a market report, but it’s not likely to be very accurate. Nor are most of the statistics that come from African governments.

There are a few reasons why good data about Africa is so hard to come by. One is logistical: the infrastructure for data gathering, in many countries, isn’t in place. In addition, the informal sector—in areas such as retail and construction materials—is huge. So are the volumes of parallel imports: the so-called grey-market products that make their way to customers through unauthorized or unofficial channels. Undercounting is a problem at all levels, even the national level, as became clear in 2014, when Nigeria raised its GDP estimate by 90%, saying it had been relying on outmoded benchmarks, and Kenya raised its GDP estimate by 25%.

A recently arrived country manager of an MNC in Kenya was startled to learn that his country’s market share was 10 percentage points lower than he had been led to believe. The company had reliable data on its own sales, of course, but had been underestimating the size of the broader market for nearly a decade, believing it had a 40% share when the actual figure was closer to 30%. A bottom-up reassessment revealed the error and led to big changes in the company’s strategy. In our experience, that sort of undercounting—and the associated overestimation of MNCs’ market shares—is a common problem in Africa. The good news is that the pie is bigger than MNCs think. The bad news is that so are the competitors fighting for it.

Africa-based companies and executives who know the continent well have adapted to the information gap by cultivating their own sources and relying on their own judgment. The success of MTN elsewhere in Africa—the telecommunications company was already offering cellular service in South Africa and Cameroon—gave it the confidence to invest in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, in 2001. The MNCs that had a chance to bid on spectrum in Nigeria were more focused on the country’s risks than on its opportunities, and as a result they held back. Today, MTN has more than 50 million subscribers in Nigeria. That has been a huge win.

Other African companies leverage their field operations to get better information. For example, in its home country of Tanzania, the beverage leader METL Group requires salespeople and managers at its 100-plus retail outlets to collect market information. Bidco uses a database of more than 6,000 consumer e-mail addresses to improve its understanding of what African consumers want when they shop for cooking products, soaps, and detergents.

Flexibility. The systems that organizations put in place as they grow are a source of power. They can also become a limitation relative to more-flexible rivals.

In the business frontier that is Africa, systemization and rules—for how decisions get made, for the qualifications someone needs in order to become a customer, for complying with regulations—can work to an MNC’s disadvantage. An international building materials manufacturer in East Africa has seen the downside of regulatory differences in its efforts to compete with local companies. The MNC sticks to its home country’s regulations about how much material a given truck can carry and how many hours a driver can be on the road—rules local companies don’t follow. As a result, those companies start with a 25% cost advantage.

African banks provide another example of flexibility. Whereas US and European banks would never offer an account or a loan to someone who couldn’t put up conventional collateral, African banks often require nothing more than a national identity card and may accept personal belongings as collateral. On a continent where traditional bank accounts are still relatively rare (only about a third of adults in Africa have them), the upside of this flexibility is huge. This is reflected in Equity Bank, which has kept the account-opening and loan-application processes simple and has seen its stock price surge tenfold since 2006, when the bank was first listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange.

Many African Lions are also more flexible than MNCs in their agreements with distributors. Western MNCs are often prohibited from working with distributors that don’t have a bank guarantee. Yet African distributors often balk at this costly requirement. Managers with extensive experience in Africa, working for a company headquartered on the continent, might be able to say of a prospective distributor, “We know these people. They’ll make good on their end.” And they might be able to apply pressure if there’s a problem. An MNC probably wouldn’t be able to do that. Its managers wouldn’t have the same knowledge of or confidence in the prospective partner, and even if Africans on staff vouched for the distributor, the decision to waive the bank guarantee probably couldn’t be made locally. The resulting delay could cost the MNC the business.

Flexibility also makes decision making more effective. If you have to wait for someone at headquarters 6,000 miles away to approve something—the purchase of an asset or the relaxation of a credit restriction for a promising customer, for example—you will inevitably miss some opportunities. At a critical point in Ghana’s ongoing energy crisis, the Ghanaian unit of Promasidor—a food manufacturer that operates across the continent—was able to secure approval quickly to buy additional generator infrastructure. Senior managers in the unit didn’t have to be brought up to speed on Ghana’s struggles, and they knew there was no time to waste. By contrast, some of Promasidor’s biggest MNC rivals were out of the market for months as they waited for decision makers in Europe to approve their purchases of generators.

To be sure, rules and structure have their place. Some African companies that don’t have enough of them have gone out of business. Still, when you hear about a deal in Africa that succeeded because of a flexible approach, it usually involves an African Lion. And when you hear of one that failed because of excessive rigidity, it’s usually a Western MNC that payed the price.

Global Companies Must Revise Their Tactics

To win new ground, MNCs need to understand how Africa’s business environment has shifted. Fifteen or 20 years ago, an MNC may have been able to establish a leadership position on the continent by building a manufacturing plant that no local company had the resources to build or by sending skilled technical and market development managers to Africa—put simply, by focusing on the transformation part of the value chain. Today, African companies in many industries have the capital and the technical capabilities to compete with MNCs. They also have a clear edge both upstream, in working with local suppliers, and downstream, in dealing with local distributors and customers.

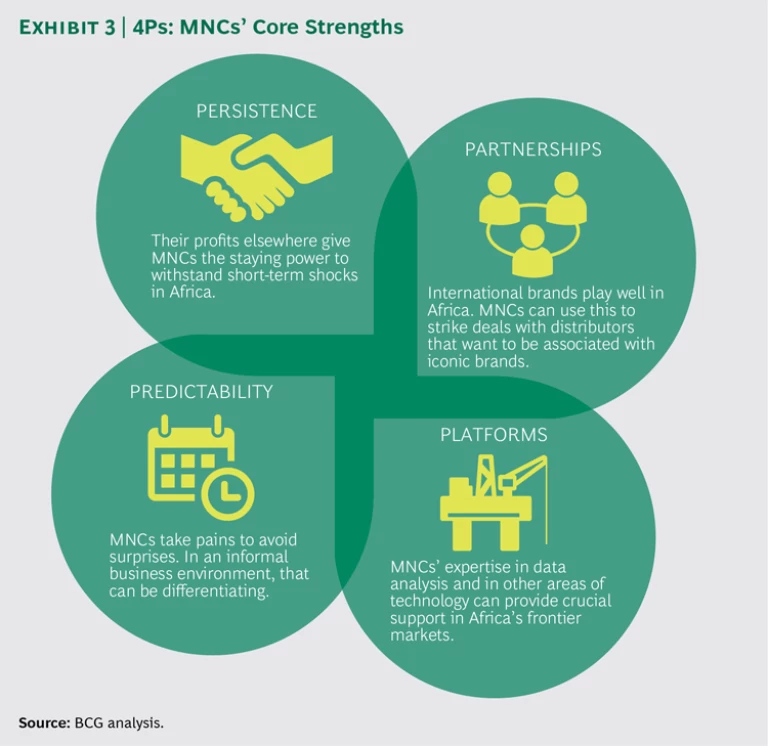

MNCs must be realistic about the extent to which they can replicate the practices of the African Lions. In many areas, they won’t be able to. But they still must develop a response to each of the four Fs. They must also exploit advantages that the African Lions don’t have: persistence, an ability to partner, robust platforms, and predictability—what we call the four Ps. (See Exhibit 3.)

Be persistent as well as focused. An MNC won’t ever be able to assign the same priority to Africa as the owner of an African business can. However, an MNC can allocate the financial and human resources to match its ambitions for Africa. An MNC may also be able to design products and business models specifically for African markets.

Moreover, MNCs have an important advantage over indigenous African companies: the ability to stay in Africa no matter what is going on there. An MNC with $10 billion or $20 billion in global sales—and hundreds of millions of dollars in profits—can keep doing what it’s doing in Africa regardless of short-term shocks. It can be wherever it needs to be and invest whatever it needs to in order to win business. That sort of persistence has allowed the logistics company Bolloré—which has been in Africa for more than 50 years and is unusual in the long tenures of its expatriate executives—to win contracts to operate ports and terminals in multiple African countries. With no significant revenue coming from other parts of the world, an African Lion cannot demonstrate such persistence.

Forge partnerships to augment field experience. It’s virtually impossible for an MNC to match the field presence of a local business. The market development staff of an MNC’s African business unit simply cannot replicate a local company’s depth of experience or degree of integration in the local ecosystem. But MNCs can do a few things to narrow the gap. For instance, they can require expatriate CEOs in Africa to serve for longer than the usual three-year stint, as successful European companies have done. They can also insist that their leadership teams on the continent include a higher proportion of Africans.

Perhaps most important, MNCs can invest in effective partnerships. For example, Coca-Cola works with independent entrepreneurs to get its beverages into small, hard-to-reach areas where the roads and infrastructure don’t allow for the use of standard delivery trucks. These so-called microdistributors, who use carts and bicycles to get Coke products to African consumers, have been instrumental in increasing the company’s sales in several East African nations, including Ethiopia. Surveys we have conducted show that people in Africa are much more likely than people elsewhere to say that established brands are inherently superior. MNCs, with their famous brands, can take advantage of that.

Use platforms to develop better facts. MNCs can’t have the kind of market intelligence that local companies have, which is a result of employing managers and staff who grew up in the area and know the customer base firsthand. But MNCs should still try to acquire and develop local talent. Indeed, this should be one of their top priorities. While they are working on that, however, they should look for other ways to get facts and figures.

One approach is to develop databases of contacts and information. Because of their resources and expertise in market research, many MNCs will be able to generate robust databases with first-rate country and consumer insights. For instance, in Nigeria, the Dutch dairy producer FrieslandCampina is developing a proprietary database of all retail points where its products are sold.

Big companies can also use their technology platforms to run their businesses more efficiently. No one likes surprises. A distributor delivering a product in an African country doesn’t want to hear that the retailer just got a delivery of the same product from another distributor; nor does a manufacturer want to find out that a retailer in a high-volume market has been without inventory for several days. The digital technology that big companies already have, or can develop relatively easily, helps limit such problems. For example, distributors can use mobile- or tablet-based applications to update manufacturers about retailers’ inventory.

Offer predictability on top of flexibility. There’s no question that local companies sometimes play by their own rules—rules not in keeping with multinationals’ health, safety, and environmental standards. But large players can certainly become more flexible by, for instance, giving local teams more decision-making authority and outsourcing parts of the value chain. In Mozambique, for example, international oil companies have adjusted to restrictions that prevent them from unloading fuel in local ports by using local providers for that activity. Indeed, many outsourcing decisions involve parts of the supply chain where African companies have an inherent advantage and MNCs must level the playing field to compete.

The Lions’ flexibility can lead to inefficiency, in the form of disorganized distribution networks. This presents an opportunity for MNCs to differentiate themselves. Consider local cement producers in Kenya, which often don’t limit the zones where their distributors can sell. That can lead to territory clashes and price competition, and can undermine the economics of a cement producer. MNCs tend to be better at anticipating such problems and more systematic in their approach to distribu-

tion zones. Coca-Cola is one of the best-in-class companies in this respect. It specifies a zone for each of its distributors in Africa, thus making their business more predictable.

The Road Ahead

To a Western executive looking for growth opportunities, Africa may seem like a riddle wrapped in an enigma. The continent’s growth is evident in the global GDP statistics and the financial results that executives can see. The many executives who have traveled to Africa for business encounter thriving markets where there once was desolation, malls where every conceivable consumer good can be bought, and infrastructure, including airports and roads, that is starting to become more modern. In parts of Morocco, Egypt, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa, the levels of mobile-phone and Internet penetration are not that different from those in San Francisco and London.

Yet for most Western companies, success in Africa has been elusive. MNCs’ difficulty holding on to market share and profitability has led some executives to wonder if the African economic boom is actually a mirage. The oil prices that have not rebounded add to the concerns.

Our counsel is to stay the course. For all the outward signs that Africa is rising—the modern buildings, the technology, the services—the real economic story involves things that are not necessarily visible: an increase in political stability and in the ease of doing business, a much higher percentage of educated workers, and, above all, a growing number of people with disposable income and the desire to progress. In many African countries, the peace and demographic dividends are just beginning to be felt.

The African Lions are certainly going to maintain their focus. But these fiercely competitive companies can learn some lessons from MNCs, just as MNCs can learn from them. The Lions can learn how to offer a more predictable experience, both to end customers and to supply chain partners. They can learn the importance of improving their operational processes. And they can learn how to approach issues of management succession.

No company, whether a Lion or an MNC, is guaranteed to win on the continent. But those that stick it out—and make the right moves—will have an excellent chance of succeeding in an economic frontier that, in many ways, is just opening up.