The poor infrastructure in China’s rugged interior hasn’t stopped S.F. Express from being able to deliver urgent contracts or parts orders to small businesses in 31 provinces within two days. Some 180,000 villages in India are so remote that they lack access to paved roads, electricity, and landline phones. Yet such villages account for 15 percent of Unilever’s $5 billion in annual sales in India. Indonesia faces an acute shortage of skills at every level. Yet each year, Astra International manages to hire 3,000 university graduates. Asia’s developing nations are supposed to be a bureaucratic nightmare for companies trying to build a regional business. Yet in little more than a decade, Malaysia’s AirAsia has built a giant low-cost carrier that has affiliates in four neighboring countries and carries 50 million passengers a year within Southeast Asia alone.

How Leading Companies Creatively Cope with Asia’s Structural Challenges

Highly entrepreneurial companies are building competitive advantage in emerging markets in Asia by creatively coping with the region’s talent gaps, overstretched infrastructure, and difficult regulatory environments.

Every company that has done business in Asia’s rapidly growing economies knows that they present some of the world’s greatest opportunities for growth. But these companies also know the deep structural challenges all too well. Thus, many industry incumbents—whether they are based in the region or abroad—still take a measured approach to investing in Asia’s emerging markets. They cautiously seek to strike a balance between opportunity and risk, waiting patiently for governments to fulfill their promises to fix the bottlenecks.

Asia’s most entrepreneurial companies don’t hesitate. Rather than be paralyzed by the region’s many obstacles, these organizations find innovative ways to overcome the barriers. Rather than wait until local conditions can accommodate new business models, they proactively help shape the environments around them. If the local pool of talent is too thin, these organizations develop their own. If regulators are slow to understand why an innovative activity is good for their economies, these companies work relentlessly to educate them.

By being shapers and first movers, the most dynamic companies in Asia’s rapidly growing economies are capturing the richest opportunities in the world’s greatest growth zone. In industries as diverse as transportation, consumer durables, and power-generation equipment, such companies are building grassroots support networks and regional footprints that will be difficult—and, in some cases, are already cost prohibitive—to replicate. In essence, emerging Asia’s first movers are not only disrupting industries but also building new barriers to entry for competitors.

The Boston Consulting Group has been tracking and helping companies master disruptive change in fast-growing developing economies for decades. We have documented the rise of global challengers—rapidly growing, internationally minded companies based in emerging markets. (See Redefining Global Competitive Dynamics , the 2014 BCG Global Challengers report, September 2014.) We have also analyzed the routes that Asian challengers, in particular, take—once they acquire scale and share in emerging markets—to become global leaders in their industries. (See Dueling with Dragons 2.0: The Next Phase of Global Corporate Competition , BCG report, June 2015.) Asian emerging markets are also rich in “local dynamos,” rapidly growing small companies that are winning in and transforming their domestic markets. (See How the Local Dynamos Win at Home , the 2014 BCG Local Dynamos report, July 2014.)

Asian companies are not the only ones proving to be masters at navigating structural constraints. Several highly flexible multinational corporations are also beating competitors to growth opportunities. To further understand how certain companies are winning the battle for growth, we analyzed five companies that have proved particularly successful at managing one or more of three structural challenges—talent, infrastructure, and the regulatory environment—in rapidly growing Asian economies. We focused on companies operating in eight economies that offer a representative mix of emerging Asia: China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. Although Singapore is a developed economy and does not present the structural challenges of the other nations in this group, we included it in our sample because it’s a business hub for the entire region.

Each of the companies we studied has found ways to cope creatively with various constraints and thereby has gained a competitive edge. The following are several examples:

- S.F. Express has been able to become one of China’s most reliable delivery services in part by directly controlling its own fleet of cargo planes and a national network of 12,000 service centers, enabling the company to reach every city in the country.

- Astra International is winning Indonesia’s talent war because it partnered with high schools, polytechnic institutes, and universities and established a comprehensive program to identify, recruit, and nurture top job candidates at every skill level across the country.

- AirAsia was able to build a regional low-cost airline by persuading neighboring governments to adopt open-skies agreements and by being willing to become a minority partner in four Asian joint ventures to comply with foreign-ownership restrictions on airlines.

The common denominators of the successful companies we studied are that they have an entrepreneurial mind-set, take a proactive approach to shaping their surrounding business environments and ecosystems, and localize their operations wherever they do business. Companies that wish to capture a greater share of emerging Asia’s strong growth would do well to emulate these traits.

With hundreds of millions of households entering the middle and affluent classes in emerging Asian economies over the next decade, the region will only gain strength as the main force of global growth. Companies must embrace the reality that the region’s structural challenges will remain issues for the foreseeable future, even with the best efforts of Asian governments. The biggest winners in the new global order will be companies that move boldly to overcome those constraints and seize the opportunities.

Emerging Asia’s Opportunities and Challenges

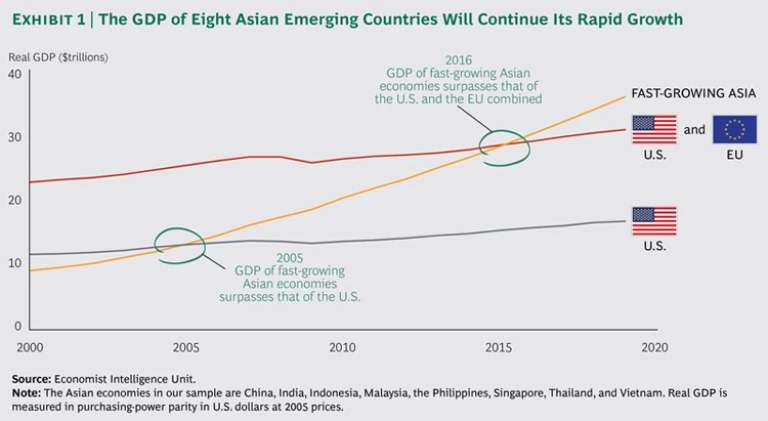

For globally minded companies, the necessity of winning in Asia’s rapidly developing economies has never been greater. Since 2009, China, India, and the six Southeast Asian nations in our study registered a remarkable 8 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for GDP. That compares with a CAGR of 3 percent for the rest of the global economy. On a purchasing-power parity (PPP) basis, the GDP of these rapidly growing Asian markets has already surpassed that of the U.S. Their GDP is on pace to surpass that of the U.S. and the European Union (EU) combined in 2016. By 2050, these Asian countries are expected to account for half of the world’s total GDP as measured in PPP and to have a per capita income roughly equal to that of the EU today. (See Exhibit 1.)

A powerful set of forces is spurring this growth. One is demographics. The population of these eight Asian economies is projected to increase by 400 million people, to 3.5 billion, over the next decade and a half. Even though the workforces of economies such as China are no longer growing, the combined working-age population of 2.2 billion of the region’s emerging markets is still expanding by nearly 1 percent a year. This population is also gaining wealth: by 2020, the number of middle-income and affluent households in emerging Asia is projected to more than double, to 630 million.

Another source of growth is regional integration. Intra-Asian trade—which increased 10 percent annually from 1990 through 2012—as well as investment and travel are rapidly binding these nations together into a giant regional economy. Southeast Asian governments are steadily implementing measures to help achieve the so-called ASEAN Economic Community 2015 goals of establishing a freer flow of goods, capital, and talent through the region. (See Winning in ASEAN: How Companies Are Preparing for Economic Integration , BCG report, October 2014.) Two other initiatives, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, seek to strengthen trade ties within the region and with the rest of the world.

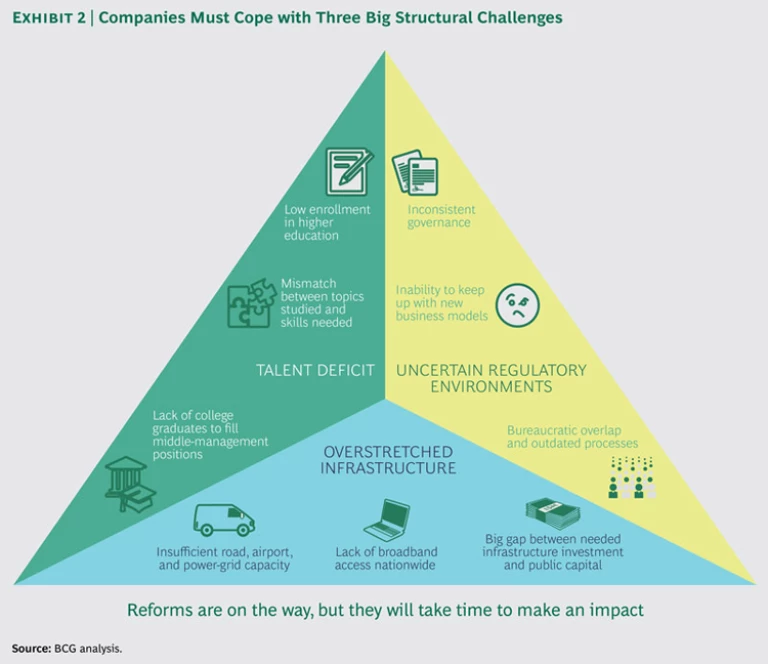

Capturing these vast business opportunities, however, requires coping with a number of serious challenges. Chief among them are the talent deficit, overstretched infrastructure, and uncertain regulatory environments, which are struggling to keep up with breathtaking change. (See Exhibit 2.) Given the different economic models and levels of development in Asia’s emerging markets, of course, the specific nature of these challenges varies.

As part of their national strategies to boost global competitiveness, Asian governments have been working for decades to overcome each of these obstacles. Many have also recently launched new initiatives backed by heavy investment. But these efforts have not been able to keep pace with the region’s rapid economic growth and the growing complexity of global business. It will take considerable time before these initiatives result in noticeable social and economic benefits.

The Talent Deficit

Despite emerging Asia’s enormous working-age population and great progress in basic education, the region’s school, university, and vocational-training systems have not been able to keep up with the explosive demand for skills at all levels. As a result, multinational corporations and domestic companies compete aggressively for a limited pool of experienced talent. (See Tackling Indonesia’s Talent Challenges , BCG Focus, May 2013.)

Although there have been dramatic gains in literacy and primary education, tertiary enrollment figures in rapidly growing Asian countries are still low by global standards. In the U.S., 94 percent of high school graduates enroll in some form of tertiary school, such as college or vocational school. In Thailand, by contrast, less than half of eligible students enroll in tertiary schools. Only about one-quarter do so in China, India, and Vietnam.

The quality of education is also relatively weak in much of emerging Asia. Although the math, science, and reading test scores of 15-year-old students in developed Asian economies, such as Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, and Hong Kong, are among the highest in the world, proficiency still lags in less-developed nations, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. The quality of higher education is also inconsistent. In India, for example, the quality of colleges and universities drops off dramatically beyond a handful of elite institutions. “We need a middle class in education,” explains Abhijit Bhaduri, the chief learning officer of the Indian IT giant Wipro.

There is also a mismatch in the education backgrounds of young workers and the skills that are in most demand by industry. Even though 34 percent of all jobs in India require technical skills, for example, 92 percent of workers have no technical or vocational training. Only 15 percent of Indian college and university graduates receive engineering degrees, compared with 45 percent who earn degrees in the arts. What’s more, much of India’s limited pool of engineering graduates is scooped up by IT companies, leaving traditional sectors, such as manufacturing and construction, starved for talent.

The supply gap for experienced managers is reaching crisis levels, driven by rapid growth in service industries. Indonesia’s service sector is projected to create up to 55 percent of all administrative and managerial jobs by 2020, compared with 36 percent today. But with only 22 percent of the college-age population enrolled in tertiary schools, Indonesia isn’t producing nearly enough graduates to fill these future positions. Even accounting for additional training, it is projected that in 2020, Indonesia’s supply of middle managers will meet only 40 to 60 percent of demand. Many companies operating in Indonesia, therefore, are likely to lack the managerial and leadership experience they need.

Most rapidly developing Asian economies are making human capital development a high priority. To help achieve the goal of making China a world leader in innovation and technology, for example, the government in 2010 launched a ten-year National Talent Plan that calls for boosting the skilled workforce from the current 114 million to 180 million. China also has a Thousand Talents Program to “import” foreign experts and to entice skilled Chinese nationals living abroad to return. Malaysia’s most recent five-year plan targets higher labor productivity and calls for transforming technical and vocational training to meet industry needs, improving the quality of education, and encouraging workers to continually enhance their skills. India has committed to spending approximately $7 billion on school infrastructure from 2012 through 2017 and has broad goals of increasing access, quality, and equity in its education system. The new Indian government is poised to release a new National Education Policy that seeks to provide “education for all.”

These initiatives should help emerging Asia meet its human resource needs in the decades ahead. They will do little, however, to alleviate the talent crunch in the short term.

Overstretched Infrastructure

Virtually anybody who traveled through Asia ten years ago will appreciate the tremendous progress the region has made in building modern infrastructure. Yet transportation, telecommunications, and energy networks have struggled to keep pace with massive urbanization, industrial investment, and companies’ needs for faster, more efficient supply chains.

The infrastructure strains in rapidly growing Asian economies were highlighted in BCG’s most recent Sustainable Economic Development Assessment (SEDA) report. (See

Why Well-Being Should Drive Growth Strategies

, BCG report, May 2015.) With the exception of Malaysia and Singapore, each developing economy in the region ranked in the bottom 40 percent of the 149 countries assessed for basic infrastructure.

In some nations, infrastructure constraints are a significant economic drag. The Indian government has estimated that, even under normal circumstances, the nation’s power grid can meet only about 90 percent of demand at current prices. The government estimates that power shortages reduce manufacturing revenue in India by approximately 6 to 9 percent a year. In 2012, blackouts affected 600 million people in India.

Asian governments are redoubling their efforts to upgrade infrastructure. To meet its development targets, Indonesia estimates that almost $450 billion in investment in infrastructure will be required just over the next five years. The government and state-owned enterprises have pledged one-third of that amount. To help fill the funding gap, the government plans to form an infrastructure bank by 2017 to attract private investors. But it remains to be seen whether such a bank will be able to raise sufficient capital to meet the country’s infrastructure needs.

Big infrastructure-funding gaps, such as the one in Indonesia, are endemic across Asian emerging markets. Although multilateral institutions, such as the Asian Development Bank and the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, can provide some additional resources, they will not be sufficient to meet the region’s needs in the short term.

Uncertain Regulatory Environments

Inconsistent governance and complex regulatory environments remain significant obstacles to capturing business opportunities across emerging Asia. With few exceptions, the region’s developing economies rate low in both the World Bank’s ease-of-doing-business rankings and the Economist Intelligence Unit’s ratings for legal and regulatory risk.

The difficult regulatory environments of developing Asian nations are commonly attributed to corruption, political interference, and local protectionism. Although these are clearly problems in much of the region, a more basic challenge is that regulatory systems are unable to keep up with rapid changes in technology, business models, and international competition. While demand for licenses and approvals explodes, bureaucracies remain paperbound and inefficient. In nations, such as India, where relationships among federal, state, and local bureaucracies are complex, the jurisdictions of ministries often overlap—compounding the regulatory burden on companies. At a time when the economic value of innovation, proprietary software, and creative content is rising in Asian emerging markets, protection of intellectual property remains weak: China, India, Indonesia, and Thailand are all on the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s Priority Watch List. What’s more, some government authorities do not understand the potential impact that new developments—such as e-commerce, rising cross-border investment, and privatization—will have on their economies. Government authorities therefore remain skeptical of adopting rules from other nations without careful analysis.

Such risks have made many companies cautious about aggressively investing in the region. In Indonesia, a draft bill limiting foreign ownership of banks to 40 percent has been under discussion for the past two years, although parliament would have the authority to allow exceptions. Such a policy could potentially force foreign institutions to sell their majority stakes in Indonesian banks.

A number of Asian governments are making regulatory reform a top priority. India’s new government has introduced a raft of bureaucratic reforms to improve the investment climate. As part of its Make in India program to position India as a global manufacturing base, the government has launched an initiative it refers to as “red carpet, not red tape.” An “investor facilitation cell” is being established to help foreign businesses quickly resolve regulatory issues. The government also pledges to overhaul India’s bureaucracy by abolishing a slew of cabinet committees and rationalizing the often overlapping portfolios of ministries. It also pledges to simplify the nation’s tax regimen.

Malaysia, too, aims to boost its attractiveness to investors by improving the ease of doing business. The government introduced an online license-approval system, abolished 405 licenses, and simplified 271 others. Such reforms have reduced the time required to set up a new business from 37 days in 2005 to an impressive 6 days in 2014. The government has also liberalized foreign ownership of banks, health care, professional services, education, and other service sectors—with more sectors to be opened in the future. In some cases, foreigners can own 100 percent of equity in service businesses.

Companies generally are taking a wait-and-see attitude toward promised reforms. Considering the sensitive politics and resistance from entrenched bureaucracies, it remains to be seen how thoroughly such measures can be implemented.

The bottom line is that companies hoping to capture the immense growth opportunities of Asia’s rapidly developing economies do not have the luxury of waiting for governments to clear away the region’s structural constraints. By that time, if it ever comes, the richest prizes will have been lost to the region’s innovative first movers.

How Leading Companies Are Clearing the Obstacles

Many industry incumbents, whether they are multinational corporations or established domestic conglomerates, still assume that they can afford to wait until Asia’s emerging markets become more developed before making big moves across the region. New competitors may be harvesting the low-hanging fruit now, the logic goes, but ultimately, the superior technology, brands, international management expertise, marketing skill, operations, and global supply chains of the incumbents will enable them to prevail.

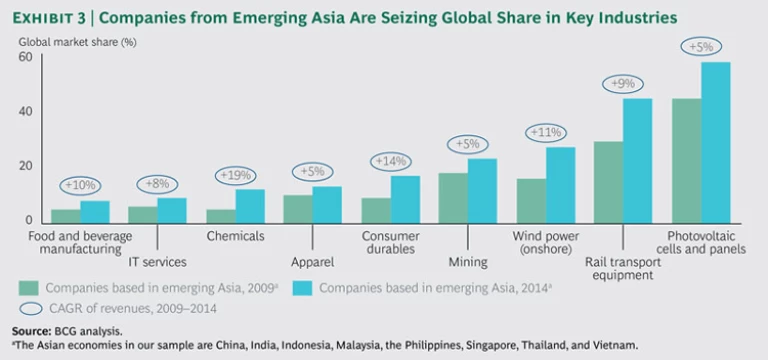

This assumption is no longer valid. The reality is that more entrepreneurial and proactive companies are seizing a greater share of the region’s biggest growth opportunities in many industries, while the share of incumbents is eroding. Many of the most dynamic companies are based in the region, and they are using their success in Asia’s emerging markets to seize a greater share of global markets in product categories such as consumer durables, food and beverage, and power-generation equipment. (See Exhibit 3.) But a number of long-established companies based in Asia and abroad are also beating the competition to growth opportunities.

Having found ways to grow rapidly by creating innovative solutions to the challenges of the talent deficit, overstretched infrastructure, and uncertain regulatory environments, certain companies with disruptive business models have built extensive local support networks and regional footprints that will enable them to sustain their growth. Indeed, several have amassed formidable competitive positions that are difficult—even cost prohibitive—for most rivals to replicate.

To get a sense of how first movers are maneuvering around important structural challenges, we analyzed five leading companies in the region and interviewed some of their top executives. Several companies, such as Astra International and Wipro, are long-established conglomerates that continue to capture some of the region’s hottest growth opportunities. Others, such as S.F. Express and AirAsia, are relative newcomers that hit the domestic scene with disruptive business models and expanded rapidly. We also interviewed Unilever, one of the world’s most successful and innovative multinational corporations in terms of penetrating Asian emerging markets. Not every company in our sample is a standout in every dimension of its business. But each has developed innovative strategies for overcoming obstacles that have slowed down other companies.

Each of these companies is a first mover when it comes to addressing challenges such as talent, infrastructure, and regulatory environments. Their innovative solutions are instructive for other companies seeking to capture Asia’s growth opportunities.

Overcoming the Talent Gap

The companies we interviewed adopted several successful strategies to recruit, train, and retain new employees in one of the world’s most competitive markets for talent.

Partnering with Local Schools. When many companies hunt for talent in emerging markets, they join the scrum at university job fairs and interview applicants who are on the verge of graduating from leading colleges and universities. Some of the best talent recruiters in Asian emerging markets, however, start getting to know young candidates much earlier and more intimately by partnering with Asian schools and sponsoring training programs.

S.F. Express, China’s fastest, most efficient courier, recruits new employees for its national courier service while they are in their final year of school at Chinese colleges and universities. The company offers students “S.F. classes,” which include a special curriculum tailored to the company’s job requirements, visits to company sites, and internship opportunities. S.F. Express invites students who pass the final examination to apply for managerial positions. Thousands of students have graduated from S.F. classes since 2008 and have eventually been hired by the company, which has about 350,000 employees in China. To ensure that the company has staff with a global background, S.F. Express has established “international clubs” at several Chinese university campuses to recruit foreign students. Graduates hired by the company have the opportunity to become managers in S.F. Express’s overseas branch offices.

Astra, one of Indonesia’s largest diversified conglomerates, hires approximately 3,000 college graduates a year for a variety of businesses that include automobile manufacturing and agribusiness. It reaches out to talent even earlier by partnering with high schools in every province of Indonesia to offer internships to students to learn technical skills. After working in Astra factories for part of their junior year, the students return to school to finish their education. High school graduates may apply for jobs at Astra as well as the company’s competitors.

To recruit managerial candidates, the company set up Astra First, a partnership with 14 Indonesian universities. The program offers scholarships and training to 80 sophomores each year. The company hopes that these students will serve as “Astra ambassadors,” creating interest in the program among other students, and become future managers. (See “How Astra Is Winning Indonesia’s Talent War—Again.”)

An especially vexing challenge in Indonesia is to recruit talent willing to work in the archipelago’s more remote provinces, given that the nation’s universities are heavily concentrated in Java. But some of Astra’s biggest skill needs are in places such as Kalimantan. Astra sponsors 445 scholarships with full room and board to attract students from remote areas to study in Java and then return to their home regions.

Astra has also been helping to develop the nation’s education system. Over the years, the company has built 13,262 schools, funded 159,620 scholarships, and been heavily involved in efforts to upgrade the quality of education in Indonesia. Astra has paid special attention to increasing the supply of graduates with technical skills. Two decades ago, Astra had to rely on a limited pool of graduates from a few foreign-funded polytechnic institutes for the skills the company needed for its fast-growing automotive and heavy-equipment manufacturing businesses. Unable to hire enough people, Astra decided to establish its own polytechnic in Jakarta.

Wipro is a leading IT services firm, with a market capitalization of $35 billion. The company has been involved in a number of initiatives over the years aimed at upgrading the overall talent pool by improving the education system. “If you expect the government to do this by itself, it will take forever,” says Abhijit Bhaduri, Wipro’s chief learning officer. Wipro Applying Thought in Schools works with more than 2,300 schools, 30 partners, and 13,000 educators in 17 states to build capacity for education reform in India. The program reaches about 1 million students directly, and several times that number indirectly, according to Bhaduri. The Wipro Academy of Software Excellence is a unique four-year program that blends rigorous academic exposure at the graduate level with practical professional learning in the workplace. Mission 10X, started in 2007, sponsors training programs for science and technology teachers at 1,300 colleges. Nearly 28,000 engineering faculty have been trained, and Wipro’s teaching methodology has been distributed by Nasscom, India’s software-industry association.

Looking Beyond Skills. Many companies that hire in emerging markets tend to rely on interviews and resumes to assess an applicant’s skills for a job. In nations, such as India, where college graduates often lack employable skills, companies also invest massively in their own in-house training programs. Wipro provides such training to more than 24,000 employees, on average, each year.

But such efforts are no longer enough: in fast-changing industries, the skills acquired in school and in company training programs quickly become outdated. “Today, a technology is terrific,” says Wipro’s Bhaduri. “Three months later, it is obsolete—and so are many of the technical skills.” In addition, many IT tasks that are now performed by humans are becoming automated. So people must learn how to keep their skills and ideas fresh and relevant.

Wipro seeks to hire candidates who will be star performers over the long term by looking beyond applicants’ current skills and paper credentials. It also assesses candidates’ personalities to determine if they are creative thinkers and agile learners and if they share the company’s values. (See “For Wipro, Talent Is About Much More Than Skills.”)

Nurturing Entrepreneurialism Within the Company. To be able to seize opportunities for rapid growth, organizations should have employees who think like entrepreneurs—workers who take the initiative and see themselves as having a vested interest in the company’s performance. S.F. Express’s founder focused on developing such a mind-set in the organization early on and has strived to maintain it as the workforce has grown.

In the late 1990s, the company asked its couriers to forgo a steady fixed salary in exchange for the opportunity to be compensated as if they were running their own businesses. S.F. Express adopted a piece-rate compensation system that is heavily based on incentives. Couriers receive a base salary of a few hundred dollars a month, but the majority of their pay is directly linked to the number of packages they deliver on time. As a result, couriers are highly motivated to improve efficiency, and as the “face of the company” for customers, they actively secure more business. “Our people are behaving like entrepreneurs,” explains the chief strategy officer, Ted Chan. “This culture is very critical here. It has helped build our brand’s reputation for excellent service.”

Systematically Grooming Executives. Astra has made particularly impressive strides in nurturing executive talent. The company sponsors a two-year, graduate-level management program for 12 to 15 candidates each year. Candidates must pass the program before they are offered jobs.

Astra has dramatically improved its ability to hire these management candidates. A few years ago, many top graduates accepted jobs at other companies, often in the banking, oil, and mining industries. In 2014, all of the management graduates joined Astra. The company also has been successful at developing managers and moving them up the ranks. One-third of the company’s 366 executives have rotated among various Astra business units. The company also constantly refreshes its executive teams. Fifty-six percent of today’s executives have been promoted from senior-manager positions within the past four years.

Active involvement by Astra CEO Prijono Sugiarto is critical to turning young managers into leaders. “I know all of the executives reasonably well,” Sugiarto says. The CEO blocks out part of his weekly schedule for regular meetings with individuals, and he makes a point of meeting managers before they go overseas and upon their return. “I don’t give many instructions. Rather, I ask questions and touch their hearts,” Sugiarto says. “In the end, it’s the passion of our people that makes the difference for performance.”

Burnishing the Company’s Reputation. Young adults across emerging Asia care increasingly about such issues as environmental stewardship, integrity, and social commitment when considering future employers. In fact, management should expect that top job candidates will have already done extensive Internet research into the company’s social-responsibility record before showing up for an interview. “We now live in a reputation economy,” Wipro’s Bhaduri says. “All of the company’s flaws and bad practices are readily accessible.”

In the battle for talent, this makes it even more important for companies operating in Asia to articulate their values and ensure that they live by them day to day. “It doesn’t matter what you say in a brochure. What people see is what you practice,” Bhaduri says.

Wipro articulated its main values in 1971; it was one of the first Indian companies to do so. What later became known as the Spirit of Wipro defined these values as “intensity to win,” “act with sensitivity,” and “unyielding integrity.” The values have been integrated into the company’s culture and hiring practices, and employees are encouraged to “hit back hard” by reporting transgressions through a variety of formal channels. The company has sought to maintain a zero-tolerance policy on violations; those paying even small bribes have been asked to leave, regardless of their tenure, performance, or importance to the business. “It is essential for our people to figure out that it is important and possible to survive by being honest,” Bhaduri says. “In an environment that is not the world’s cleanest, a reputation for integrity can differentiate you.”

Wipro’s record of upholding its values has been recognized by a number of international organizations. The Ethisphere Institute, a business ethics think tank, has ranked Wipro as one of the world’s most ethical companies for the fourth year in a row. Climate Disclosure Leadership Index rates Wipro as a leader in disclosing its carbon footprint. The Dow Jones Sustainability Indices and Greenpeace rank Wipro as a global leader in sustainable practices among IT companies.

Astra also believes that its reputation for strong values gives it an edge when competing for top talent. In addition to making charitable contributions to public education, the Dharma Bhakti Astra Foundation—established by Astra founder William Soeryadjaya in 1980—works with some 8,800 small and midsize enterprises across the country to promote job creation and economic development. “These activities are good for the economy and provide employment opportunities,” says Sri Martono, Astra’s chief of corporate human-capital development and head of the foundation.

Coping with Inadequate Infrastructure

Fast-growing companies have developed a number of innovative strategies to cope with infrastructure bottlenecks that can impede growth.

Controlling the Transportation Fleet. The secret behind S.F. Express’s ability to deliver parcels anywhere in China in one or two days despite the country’s overstretched transportation infrastructure is that it is the only private courier service in China that owns its own fleet of cargo planes. Most other couriers still focus entirely on trucks and typically have slower delivery times. As a result, S.F. Express has achieved an edge in rapid delivery that few rivals can match. (See “How S.F. Express Can Guarantee the Fastest Delivery in China.”)

Going Digital. One of the most promising ways to overcome the constraints of physical infrastructure in remote areas of emerging Asian markets is to rely more heavily on digital technologies. Access to the Internet through mobile devices and personal computers is growing explosively across the region, enabling leading companies to reach and serve consumers and businesses far more efficiently.

Unilever uses digital technology to create and maintain digital profiles of the small, family-owned shops that account for the majority of its retail sales in nations including Indonesia, Vietnam, and India. This data, collected on handheld devices by Unilever’s representatives, allows the company to gain a better understanding of these shops and so improve in-store product placement and plan distribution routes. (See “Unilever: Enabling Mom-and-Pop Shops with Digital Technology.”)

Participating at the Grass Roots. Many villages in emerging Asia are so disconnected from telecommunications infrastructure that consumers cannot be reached through conventional distribution systems. In some cases, the only radio or TV in a village may be in the hut of a village headman. As a result, for many multinational corporations, villages represent a giant, untapped market. In India, such remote villages account for 15 percent of Unilever’s annual sales.

To reach these isolated households, Unilever embeds itself in village life through initiatives such as Project Shakti, a program that blends business development with grassroots economic development. Working with nongovernmental organizations and village assemblies, the project identifies women who are respected locally, understand local needs, and are willing to become the company’s trading partners. Project Shakti offers business training and microfinance credit so that the women can set up their own businesses to distribute Unilever products—often selling door to door. The Shakti ammas, or mothers, thereby contribute to the village economy. Beginning with only 60 villagers a decade ago, Project Shakti now has more than 60,000 entrepreneurs running profitable businesses. For its part, Unilever has an entirely new distribution channel in important new markets.

Avoiding the Congestion. How could AirAsia quickly build a regional network of low-cost flights despite growing congestion at many airports in emerging Asia? “We have faced some challenges, but we have overcome constraints by developing many unique destinations in Asia that remained untapped,” explains AirAsia’s CEO, Tony Fernandes. One in three AirAsia routes, in fact, had never been flown before the carrier inaugurated service. In 2004, for example, AirAsia became the first low-cost carrier to connect Kuala Lumpur with Bandung, Indonesia. By 2011, it was flying that route 28 times a week, carrying 300,000 passengers annually.

AirAsia has also tended to use second-tier airports as regional hubs because more slots are available, fees are lower, and congestion is lighter than in the region’s busiest airports. To overcome challenges at Hong Kong’s highly congested airport, for example, AirAsia developed Macau as a secondary airport. In the Philippines, the airline launched service at Clark International Airport, rather than at the crowded Ninoy Aquino International Airport in Manila. And in Bangkok, AirAsia developed a hub at Don Mueang International Airport, rather than at the newer and much larger Bangkok International Airport. Since AirAsia began service at Don Mueang in 2004, annual passenger traffic to Kuala Lumpur has surged from 58,000 a year to more than 420,000.

Navigating Regulatory Environments

Entrepreneurial companies in Asia’s rapidly developing economies have honed a number of strategies to navigate the region’s regulatory environments, which are struggling to keep pace with new technologies and business models. The following are some of the approaches frequently cited by the companies we interviewed.

Finding Creative Ways to Exert Control. One of the most attractive options for entering a new emerging market in Asia is to form a joint venture with a domestic partner. Yet even though most Asian governments have liberalized rules on foreign direct investment in recent years, they still bar foreigners from owning majority stakes in certain industries—a serious stumbling block for companies that want to control their businesses.

This hurdle did not stop AirAsia from successfully establishing low-cost carriers in four neighboring countries. The airline was willing to be a minority partner in joint ventures, but it has been circumspect in its choice of partners. And except for a venture in Japan, AirAsia’s joint-venture partners tend to have no airline experience. Still, thanks to the company’s management and a trusting relationship among its partners, it has been able to exercise control over operations. (See “How AirAsia Became a Regional Power as a Minority Partner.”)

Helping Shape Regulations. Regulatory authorities in emerging Asian economies can often be more receptive to sound policies and best practices than many companies assume. But regulators are wary of adopting new concepts and borrowing rules and regulations from other nations without careful study. Regulators want to understand the implications of changing the rules or authorizing new business activities in their country.

Companies at the forefront of innovation in emerging Asia have had success in winning approval for their businesses by patiently explaining the benefits to regulators. AirAsia’s Fernandes has been a leading advocate of deregulation in the Asian airline industry for years. Soon after he bought the carrier in 2001, he began a lobbying campaign with Malaysia’s prime minister at the time, Mahathir Mohamad, to convince other Southeast Asia governments to adopt open-skies agreements.

Fernandes says authorities around the region have also been receptive to the company’s business model because they understand how it can contribute to their economies. AirAsia has a government relations, policy research, and outreach department that seeks to educate stakeholders and regulators in meetings and various forums. Among other things, AirAsia points out that low-cost carriers contribute more than $250 million annually in passenger service charges to airports in Southeast Asia and $6 billion indirectly in tourism spending within the region. “Generally speaking, AirAsia has benefited from regulators across the region that have been supportive of trying to facilitate the growth of low-cost airlines to benefit their economies, specifically the trade and tourism sectors,” he says. “Their support has allowed AirAsia and many other low-cost carriers to make Asia-Pacific one of the fast-growing aviation markets globally.”

Unilever invests considerable time in new Asian markets educating regulators on the policy options available to them on the basis of the company’s decades of experience in other developing economies. “We are familiar with tackling diverse regulations across different markets,” says David Kiu, Unilever’s vice president of sustainable business and communications. “This gives us a competitive advantage over local companies that are only now trying to regionalize because they are used to only one set of regulations in their home countries.” Locally based Unilever officials are active in regional associations (such as the ASEAN Food and Beverage Alliance) that advise governments on food and safety regulations. “We try to proactively help governments shape regulations by being part of the solution and by having a seat at the table, even in markets such as Myanmar that we entered relatively recently,” explains Kiu.

Wipro has a long history of working closely with India’s government. An important tenet of its engagement is to develop a well-articulated business case for the government and regulatory bodies that details the economic benefits of the company’s investments.

During its infant years in the 1990s, India’s IT-services outsourcing industry ran into a regulatory wall. “The business models were new and unexplored in India,” explains Ashutosh Chadha, Wipro’s head of corporate affairs. “There were regulatory challenges spanning a broad spectrum of areas.” Among those challenges were securing the recognition of IT services outsourcing as a valid business and qualifying for government benefits as an export industry. Another challenge was to frame labor laws so that they would allow operations to work 24/7. Wipro engaged with the government to draft new health, safety, and security regulations for employees. Securing access to seamless Internet connectivity and electrical power was a particular challenge at a time when the country faced serious infrastructure bottlenecks. Procuring land that had been earmarked for the manufacturing industries was another issue.

To increase support for sweeping regulatory changes and to secure key government approvals, Wipro worked with industry organizations to highlight the economic contributions of the IT services outsourcing business, such as job creation and higher inflows of foreign direct investment. “Our corporate affairs group and business group work hand in hand to help achieve these objectives,” Chadha pointed out. “The conversation is always around the economic impact over the long term for the country and government by putting them first.”

A current priority has been to improve India’s system for acquiring an export license, which requires filing multiple applications at both the local level and in New Delhi. Due to slow processes, licenses that should have been granted in a couple of weeks often take up to three months to be processed. Wipro has worked with the government to promote changes to move the system online. This has made approvals faster, smoother, more efficient, and transparent. Wipro is also working with Indian regulators on labor laws, cyber-security, procurement, tax policy, and foreign trade. Wipro’s approach is to demonstrate how regulatory changes could help advance the agenda of the government and make the country more business friendly. “If you want to be seen as a trusted advisor, you need to sit on both sides of the table,” Chadha says.

Earning a Social License. One of the worst nightmares of a company that is quickly seizing market share in a developing Asian economy is that its success will provoke a public backlash. Whether fair or not, negative domestic-media coverage and protests against companies that are seen to be damaging public interest in the name of profits can often lead to regulatory actions as well.

One way that some fast-growing companies in emerging Asia have averted such backlashes is by earning the goodwill of local populations. Because of Astra’s extensive involvement in developing the nation’s education system and other corporate-social-responsibility programs, “we have the advantage of being a trusted institution,” Sugiarto says. “We experience a lot of scrutiny because we have been very successful economically. But a lot of stakeholders see Astra as an important national asset.”

Unilever also believes that its grassroots community-development activities in Asian emerging markets generate public support for the company. “We focus on building a social license to operate in emerging markets. Our India office has a motto that goes, ‘What is good for India is good for Unilever,’” Kiu says.

The specific strategies that fast-growing Asia’s first movers have developed to hurdle the region’s structural barriers are instructive. For many companies, it is either too late or too demanding of time and resources to gain much competitive advantage by replicating them. But these actions illustrate the kind of corporate mind-set that allows companies to create their own innovative solutions.

Seizing the growth opportunities in Asia’s rapidly developing economies is critical for any globally minded company. But make no mistake: the structural challenges that complicate the business landscape today will remain obstacles for the foreseeable future. Governments are redoubling their efforts to make their economies more competitive by improving their talent pools, infrastructure, and regulatory systems. But change will not come fast enough for most companies.

To seize lasting competitive advantage and be a leader in Asia’s immense, swiftly evolving growth markets, most companies will require a shift in mind-set. They should do more than adapt to a problematic environment. They should work actively to shape it.

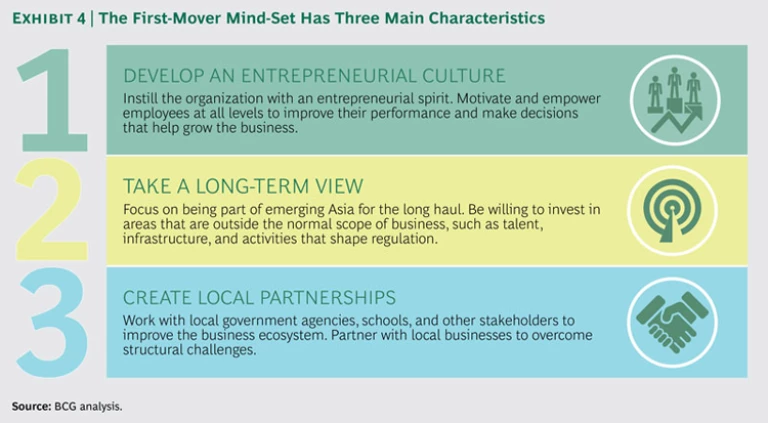

We see three main characteristics of such a first-mover mind-set. (See Exhibit 4.)

Toward a First-Mover Mind-Set

- Develop an entrepreneurial culture. Companies need to cultivate an organization in which employees at all levels seek to improve their own performance and that of the overall business. Companies should consider offering performance-based incentives and empowering employees to make decisions that are beyond their usual roles in order to grow the business. For many organizations, this will require a cultural change.

- Take a long-term view. To be leaders and shapers in Asia’s rapidly developing economies, companies must remain focused on long-term goals, not only the next few quarters. A willingness to invest in talent, infrastructure, and efforts to shape regulation, as well as other areas beyond the normal scope of business, is evidence of this commitment. This willingness requires companies to take a different approach than the one normally practiced by MBAs when evaluating the business case for any investment.

- Create local partnerships. Leaders in rapidly developing Asian economies recognize that their companies are part of an ecosystem and that their success is intertwined with that of other stakeholders. A willingness to localize and a spirit of partnership are important. Rather than view regulators mainly as potential adversaries, companies should work with them to help create an effective regulatory system that advances the agendas of their business and that of local governments. Companies should partner with schools to bolster the education ecosystem and develop the talent pool that their businesses need. Companies should also be open to joint ventures that can accelerate growth and help overcome obstacles. While seeking to maintain control over technical operations, companies should be willing to cede majority financial control if necessary.

Where change cannot be easily achieved, companies must be flexible enough to adapt to conditions as they are in emerging Asia. Organizations have to discover their own ways not only to cope with the challenges but also to grow their businesses despite the limitations. Companies need to accept different degrees of risk and, without compromising their core values, different governance norms. And companies have to rethink long-held attitudes toward financial control of joint ventures if they are ever to become Asian players in protected industries, such as banking and telecommunications.

Companies that retain a narrow vision of their operations in emerging Asia risk being frozen out of the world’s greatest growth markets. These companies will cede the richest opportunities to first movers that are working creatively and persistently to change the environment to accommodate their needs and business models. These entrepreneurial companies grasped long ago that the real barriers to entry in Asia’s rapidly developing economies are not talent, infrastructure, and regulation. They are a company’s own mind-set.

Acknowledgments

This report would not have been possible without the efforts of our BCG colleagues Aparna Bharadwaj, Sumit Dora, Rishab Gulshan, Yung Shen Ow, Evelyn Tan, Kanchanat U-Chukanokkun, Sharad Verma, and Praipim Vutivijarn, as well as our former colleague Handian Lo. We also thank Pete Engardio for his help in researching and writing this report.