Over the past few decades, the rise of emerging markets—initially as sources of cheap labor and then as rapidly growing consumer markets and centers of capital investment and innovation—has caused most companies of size and stature to enlarge their global ambitions. But despite this concerted push to globalize, few companies are ready to build and run truly global organizations and operations.

- Only about 10 percent of companies believe they have the full complement of capabilities required to win overseas. Most companies are barely mastering the basics.

- A smart strategy is necessary but insufficient. The winners in globalization also execute better than their competitors.

- Companies struggle with three specific areas overseas: strengthening their go-to-market, logistics, and other value-chain activities; aligning their organization to support the global agenda through, for example, the spread of best practices; and mastering mergers and acquisitions.

- Line managers who run businesses or regions are much more pessimistic about their companies’ global readiness than headquarters staff.

- Midsize companies are at the greatest risk in going global. They are less nimble than smaller companies and do not have the scale or systems of larger ones.

Those are the primary messages of the Global Readiness Survey, which was conducted jointly by BCG and IMD business school. (For details on our methodology, see the sidebar “What We Asked, Whom We Surveyed, How We Scored.”) In this report, we explore our findings and take a detailed look at what separates the leaders from the laggards in globalization.

What We Asked, Whom We Surveyed, How We Scored

Respondents to the survey were asked to respond to 24 statements on a six-point scale ranging from “completely disagree” to “completely agree.” We converted these responses into a percentile score, with “completely disagree” represented by 0 percent and “completely agree” represented by 100 percent. In this report, “score” refers to the average percentage for an answer.

The 362 executives surveyed work for a wide variety of companies throughout the world. Slightly more than one-half of the respondents, or 56 percent, work for companies based in Western Europe; 11 percent are at North American companies; 9 percent are at either Latin American or Japanese companies; and 6 percent are at companies in emerging Asian markets. The rest are scattered throughout other parts of the world.

One-quarter of the respondents work for industrial goods companies; almost as many, 21 percent, work for consumer products companies; 15 percent work for technology, media, and telecom companies; and 6 percent work for either financial institutions or professional services firms. The remainder work in health care, energy, insurance, the public sector, and other industries.

Global Ambitions, Yes; Global Readiness, Not Yet

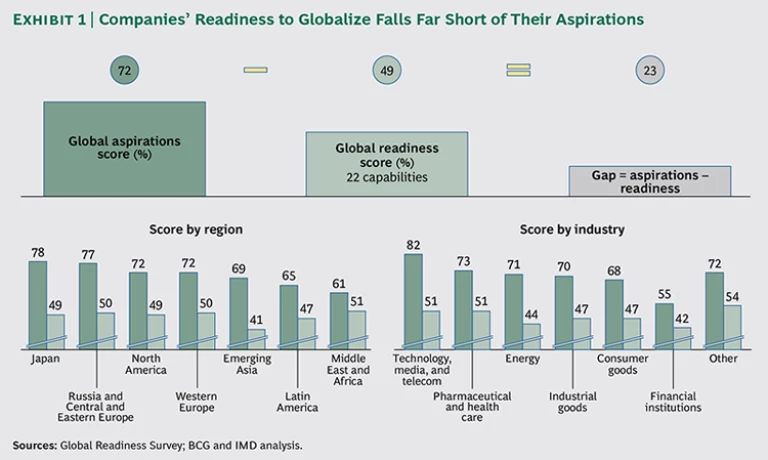

The survey posed a set of 24 questions about globalization. Two of the questions specifically addressed ambition. The average ambition score was 72 percent (100 percent signifies that globalization is the company’s top priority). In line with this relatively high level of ambition, 75 percent of companies plan to increase their international share of business. Aspirations vary by industry, with technology companies the most bullish and banks the most conservative. Globalization ambition also varies by region, but to a lesser degree.

The remaining 22 questions assessed the readiness of companies to be successful overseas. Executives were much more critical of their companies’ readiness than of their ambition. The average score on these questions was 49 percent. Only one in ten respondents said they thought their companies were mastering the basics—with a score exceeding 50 percent—across all 22 capabilities. For 15 of the 22 capabilities, the average score was below 50 percent.

Clearly, a yawning gap exists between aspiration and readiness. (See Exhibit 1.)

To shed light on this gap, we divided the 22 questions about readiness into four groups of capabilities:

- Learning and Agility: the willingness of a company to understand and adapt to local markets by developing new products and services and by modifying its business model. Chinese appliance maker Haier, for instance, has succeeded by focusing on the unmet needs of consumers overseas. In India, Haier sells a washing machine that operates at low water pressures, while in Nigeria, it sells refrigerators with generators and thick insulation to deal with frequent power outages. Respondents consider this group of capabilities to be their greatest strength, with an average score of 54 percent, still far lower than the average ambition score.

- Leadership and Governance: the strength of commitment from the top in pushing a global agenda, establishing global priorities, and aligning performance incentives. General Electric exemplified strength in leadership and governance when it gave profit-and-loss responsibility and significant product and go-to-market authority for products to select country businesses. Respondents gave their companies a readiness score of 53 percent on these capabilities, the second-highest score after ambition to globalize.

- Business Capabilities: the core business skills needed to compete in complex markets, such as global supply chain and go-to-market capabilities. Coca-Cola, for example, has created distribution models built around strong relationships with individual franchisees. The combination of localized distribution and centralized global marketing has proven to be a powerful one-two punch: Coca-Cola is the undisputed global market leader in soft drinks outside its home market. Companies’ average readiness score on business capabilities was 46 percent.

- Organizational and Executional Alignment: the ability of a company to devise organizational processes suited to global markets, to adapt internal systems to the global agenda, and to effectively manage the relationship between headquarters and local business units. Nestlé’s Global Business Excellence (GLOBE) initiative, for example, has created a common set of global best practices and a common IT infrastructure. GLOBE’s goal is to make Nestlé “more united and aligned on the inside to be more competitive on the outside.” This group of capabilities presents companies with their biggest challenge, with an average readiness score of 45 percent.

The Strategy Execution Gap

In the past, most executives viewed globalization as a strategic challenge: Is geographic expansion a leadership priority? Are we pursuing the right markets? And have we adapted the product portfolio to those markets?

The Global Readiness Survey shows that many executives are increasingly comfortable with the strategic readiness of their companies. Many of their strongest capabilities are strategic. For example, leaders place a high priority on the global agenda, and the company is able to adapt the product portfolio to local needs.

By contrast, executives are much less confident about their companies’ ability to actually get things done overseas. For example, establishing a global supply chain and a locally adapted go-to-market approach—necessary ingredients of a truly global organization—rank in the bottom third of capabilities.

The imbalance between strategic and executional abilities becomes especially evident when we look at four pairs of questions that address both a strategic component and a corresponding executional component. In all four cases, executives rate their companies’ strategic ability higher than the corresponding executional ability. (See Exhibit 2.)

Two examples:

- Senior management is good at giving priority to global activities but does a below-average job at funding those projects. In other words, they talk the talk but don’t fund the walk.

- Likewise, headquarters staff supports the global agenda but falls short in one of the primary roles of the center: spreading best practices related to globalization throughout the organization.

Intense Local Competition Raising the Stakes

Execution will have an ever-greater impact on the performance of business abroad as companies run into highly competitive local companies. One third of respondents consider small-to-midsize local players to be their fiercest competitors. In some industries, such as industrial goods, more than 40 percent of respondents are most worried about local competitors.

Small and midsize local companies are less complex and place a greater focus on executional excellence. They are agile, efficient, and responsive to local customers. They are able to win against global companies that are several times their size and have more sophisticated technological skills.

In many emerging markets, these local companies, which we call local dynamos, are often able to outgrow multinationals by 25 percentage points annually.

The implication for global companies is clear: a good strategy is not good enough. They need to execute better. Senior executives need to set clear operational targets, monitor progress, and provide funding.

Tackling the Hardest Challenges

As noted earlier, among the four groups of capabilities, companies are weakest at business capabilities and organizational and executional alignment. Among individual capabilities within the four groups, the weakest by a wide margin is M&A.

Business Capabilities. Many of the weaknesses in this area, such as in supply chain and go-to-market activities, are not surprising because these are capabilities that require large investments, deep experience, intimate local knowledge, and—perhaps most important—strong local talent.

The last point is especially noteworthy. Respondents say that their companies are comparatively good at sourcing local talent where available. But the lackluster performance in business capabilities suggests that local talent development needs to be much stronger. The challenges in local go-to-market and supply chain activities suggest a need for senior local leaders with strong functional and industry expertise, who know how to achieve lasting change on the ground. Indeed, our global clients tell us that developing and retaining local talent is one of their top three challenges, especially in rapidly growing markets.

Organizational and Executional Alignment. Having a governance model that balances direction and oversight and ensuring that internal systems are adequate for a global business do not require local insights or specialized knowledge. The challenge is internal: how to act as one company to maximize success in each global market.

It turns out, however, that internal readiness is hard to achieve. Notably, companies need to redesign reporting relationships between regions and the center. The center needs to effectively support the global agenda, provide leverage, exploit global scale, and impose strong governance. At the same time, it needs to leave room for adaptability, nimbleness, speed, and authority in local markets. HR and IT may need re-wiring. Finally, companies should actively support the establishment of global networks within the organization and a mind-set that is open to globalization.

The Japanese pharmaceutical company Takeda, which grew internationally between 2005 and 2011 through acquisitions in Europe and the U.S., provides a good example of such a campaign. As part of its transformation into a more global company, Takeda made changes in the company’s structure by moving core business functions out of Japan. This sent a strong signal that the company was becoming less “Japan-centric.” It reinforced this view by naming non-Japanese executives as chief financial officer, chief HR officer, and head of business development. The company also overhauled HR policies and systems to support the new global orientation.

Mergers and Acquisitions. Global expertise in M&A had the lowest overall readiness score, at 34 percent, in large part because it takes so many steps—target selection, due diligence, and integration—to complete a successful deal. Companies also reported weakness in several capabilities, such as establishing effective support from the center, that are essential for a successful postmerger integration.

Still, strong M&A capabilities can be transformative. Companies that do well on this capability have much higher overall scores on the Global Readiness Survey. Companies scoring 75 percent or higher on M&A reported total readiness scores at least 10 percentage points higher than average.

Successful M&A deals allow companies to acquire market share and a global footprint, diversify their talent base, and create a more varied portfolio of businesses. Cemex, for example, has evolved over the past 30 years from a midsize Mexican concrete manufacturer into a global leader through a series of acquisitions. Along the way, it codified a set of steps for PMI. During integration, the company rapidly rolls out highly standardized core processes but also identifies those practices of the acquired company that should be shared. Cemex staffs its integration teams with high-potential junior managers who try to strike the right balance between efficient integration and an open mind-set.

Overcoming the Rift Between Headquarters & the Business Units

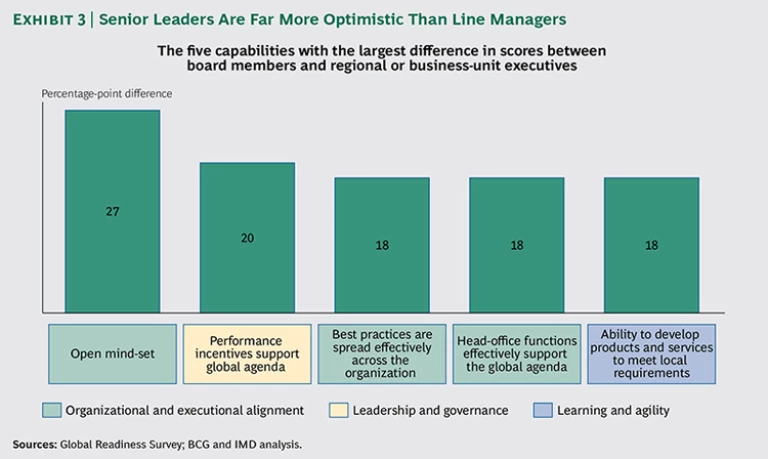

Executives at headquarters have a far more optimistic view of their companies’ globalization readiness than executives working in the field. This disconnect suggests either that executives working within the business units and regions are too caught up in their daily chores to see the overall progress of the company or that headquarters staff are out of touch—or both.

A look at the capabilities with the biggest differences in readiness scores between board members and line managers is revealing. (See Exhibit 3.) Line managers reported a severe lack of organizational and executional alignment as well as misaligned performance incentives. They were much more skeptical of their company’s ability to develop products to meet local needs. All of these deficits are cause for poor performance, especially in the face of growing local competition.

Stark differences in perception between headquarters and the business units should serve as a warning sign for senior leaders. As the battleground shifts from strategy to execution, the ability to read signals from the front line is becoming ever more important.

Many companies are addressing this gap. But only a few are actively managing the relationship between the center and the field:

- Increase headquarters’ exposure to markets abroad. Holding board meetings in emerging-market cities and making visits to consumers, customers, NGOs, and government agencies are increasingly routine. Some companies, such as hotel chain Starwood, are going even further. Starwood moves its headquarters staff to Mumbai, Shanghai, and Dubai for month-long rotations and has permanently relocated several key staff functions.

- Develop geographic diversity among senior management. In many companies, an international assignment is an essential way station for rising stars. But these episodic postings do not necessarily create champions for overseas markets. Companies should develop actual diversity in their senior management teams. Their goal should be to have several C-level executives who have built their careers around success abroad.

- Re-examine the matrix. Many companies constantly tweak the relationship among headquarters, business units, and regional businesses, often by adjusting decision rights and processes. The biggest bang often comes from the boldest move, such as General Electric’s experiment with flipping the matrix and giving substantially more power and authority to local businesses in key markets. (See the sidebar “Local Power.”)

LOCAL POWER

Many companies still try to improve the performance of their overseas businesses from headquarters. They conduct product and market analyses and determine budget allocations for business units and regions. This “headquarters bias” can backfire when the business units are competing against strong local companies and need more authority to make faster decisions.

In these markets, it makes more sense to conduct analyses and determine needs at the local level and then define the role that the central functions can play. Local leaders are the best people to decide which types of innovation and which go-to-market approach are required. They should also have input into the decision rights they require to win locally.

Headquarters staff and centralized functions will still play a critical role in sharing best practices and taking advantage of scale. And they will still have to make tough decisions in allocating scarce resources among competing local businesses and regions. But they need to see their role as supporting the business units, not merely overseeing them.

For many multinationals, these are fundamental shifts in the way they run local businesses. But these measures will not stick unless senior leaders create a vision and a strategy around the importance of overseas markets supported by KPIs that are built into performance evaluations and compensation metrics.

Size Does Matter

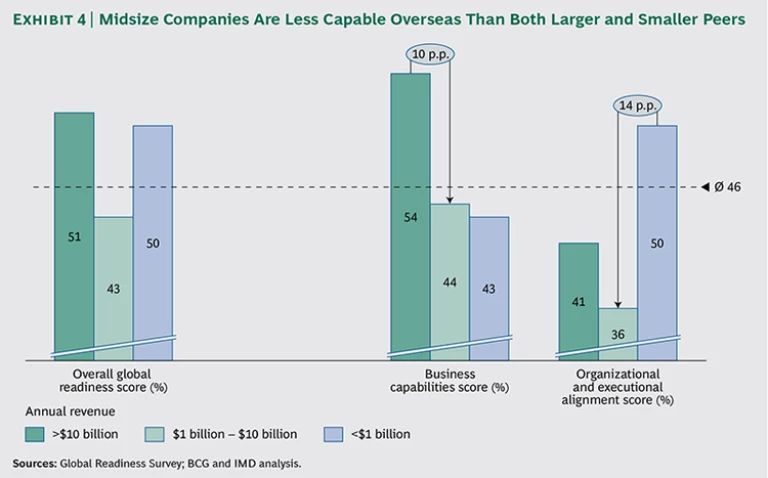

Small, midsize, and large companies have similar globalization aspirations, but vast differences separate their readiness to globalize. (See Exhibit 4.)

Most strikingly, midsize companies, with $1 billion to $10 billion in annual revenues, underperform their larger and their smaller peers across most capabilities. They have neither the scale of large organizations nor the agility and effectiveness of smaller ones.

Large companies do better than midsize and small companies in such core business capabilities as setting up a global supply chain. Scale and experience clearly are advantages. But large companies do relatively poorly on capabilities related to learning and agility. This weakness makes them vulnerable during periods of rapid change, a situation that may be exploited by smaller and more agile local players.

Small companies, on the other hand, are fleet-footed but have no mastery of local markets and may misunderstand their competitors abroad. While executives of small companies tend to believe that small and midsize companies are their strongest competitors at home, they see multinational companies as the biggest threat overseas. This suggests that they may not have screened the competitive landscape abroad sufficiently well.

Where Leaders Outperform Laggards

In order to understand the specific capabilities that separate strong from weak globalizers, we divided them into two groups, leaders and laggards. Both have high globalization aspirations. The difference is that leaders match their aspirations with strong execution while laggards do not.

Leaders and laggards perform similarly on a handful of capabilities, mostly in leadership and governance and in learning and agility. (See Exhibit 5.) However, the gap between leaders and laggards exceeds 40 percentage points on more than half of the 22 capabilities unrelated to aspiration, nearly all of them in the categories of business capabilities and organizational and executional alignment.

Laggards are especially weak at closing capability gaps, handling complex global businesses, creating internal systems suitable for a global company, and adapting processes for global expansion. These findings again suggest that execution, not strategic capabilities, separates success from failure. Leaders align their organization with their global aspirations and create a high-performance machine on the ground in local markets.

Executing the Global Agenda: What It Takes to Win

Globalization is not a simple or a singular activity. As the survey makes evident, companies need to attack it from many angles. They need to embark on a transformation that combines the right strategy with better execution. This transformation should be consistent with the following two imperatives:

- Ensure internal readiness. Global functions play a crucial role in realizing the scale advantages of a global organization. However, they often do not deliver. Executives need to ask themselves:

- What is the role of the center in relationship to our regional businesses? Where and when do functions add value, and where are they a hindrance to local success?

- Are we using technology to break the compromise between local adaptation and global scale?

- Develop stronger on-the-ground capabilities and involvement. To reap the full benefits of their global agenda, companies need to improve local capabilities, especially the development of local talent. Leaders should answer the following questions:

- Have we reoriented our talent development processes so that local managers are fully committed to the success of their business unit or region? Or do we still use businesses abroad as stepping stones for promising managers from headquarters?

- Are local leaders just feeding data into the corporate planning and strategy processes, or do they play an active role in devising the strategy?

The bar for successful globalization is rising. It’s not enough for globalization to be a priority. Senior leaders need to ensure that their companies embrace globalization as a live-or-die proposition. For many companies, the stakes are that high.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the executives who completed the survey, without whose time and efforts this report would not have been possible. They also thank their BCG colleagues Sumit Dora and Peter Ullrich for research, analysis, and writing assistance.