Top executives intuitively understand that they cannot win without the right people and the right skills. In surveys, they consistently rank leadership and talent management at the top of their agenda but express frustration with the return on their investments in this area. (See Creating People Advantage 2014-2015: How to Set Up Great HR Functions , BCG Creating People Advantage report 2014-2015, December 2014.)

Unlike other disciplines, such as corporate finance, leadership and talent management is a relatively undeveloped field in the application of data- and evidence-based approaches to value creation. Most companies do not address the most fundamental questions around leadership and talent development, despite huge expenditures—$40 billion annually by some estimates. Still, some companies get it right. Not surprisingly, these companies tend to be market leaders in their industries.

The BCG Global Leadership and Talent Index (GLTI) is the first tool to precisely quantify a company’s leadership and talent management capabilities. It is the product of a multiyear effort that culminated in a recently completed study of more than 1,260 CEOs and HR directors at global companies.

WHOM WE SURVEYED AND WHAT WE ASKED

The 1,263 executives surveyed work for a wide variety of companies around the world. We allowed only one respondent per company. Slightly more than half the respondents, or 55 percent, work in professional services, industrial goods, consumer goods, and the public sector. Technology, media, and telecommunications companies and financial services companies accounted for 17 percent of the sample, followed by health care, energy, and “other.”

The respondents were based in 85 countries altogether. Forty percent were based in Europe and 30 percent in Asia, of which 19 percent were from emerging markets within Asia. The Americas, with 23 percent; Africa, with 3 percent; the Middle East, with 2 percent; and “other” made up the rest of the sample.

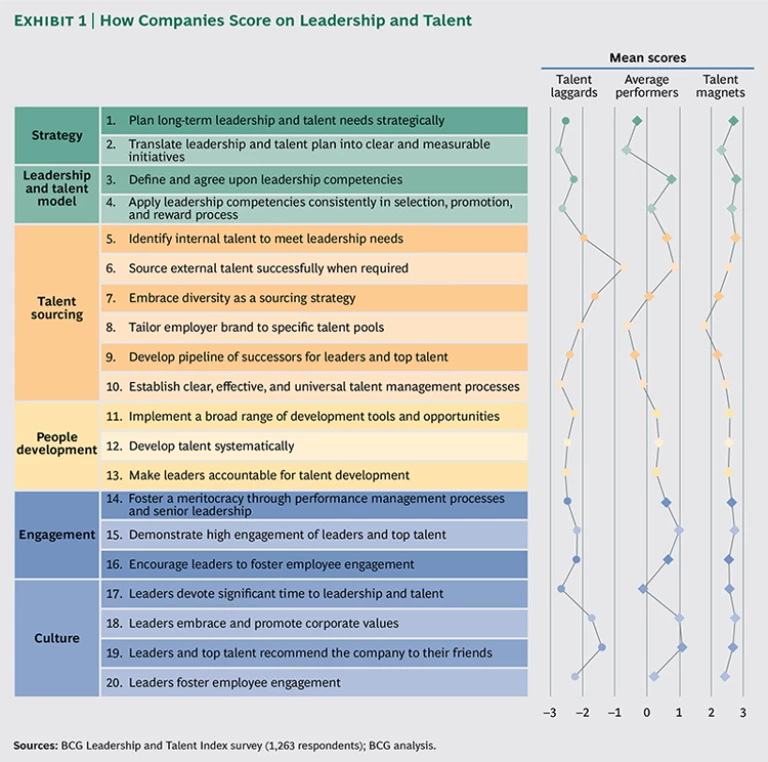

We divided leadership and talent management into 20 specific capabilities, grouped into six categories. We asked executives to assess their company’s relative strength on each of these capabilities on a six-point scale, from –3 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree).

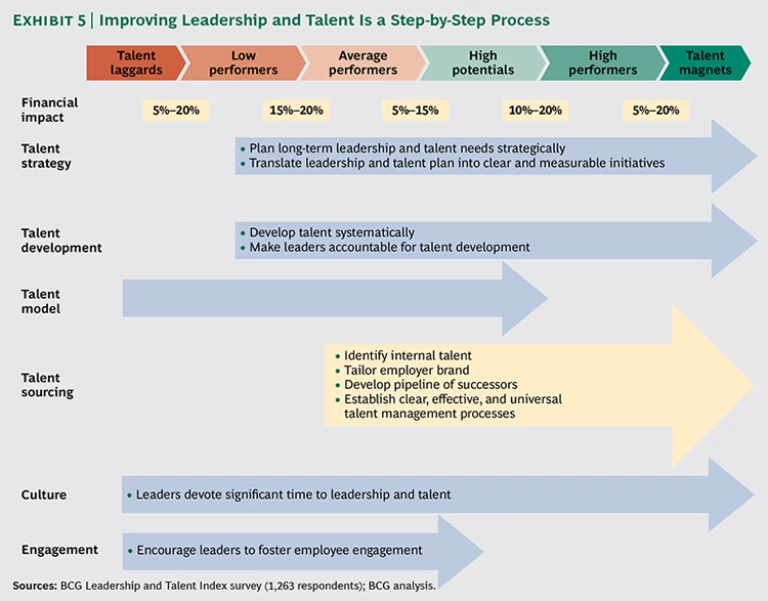

Based on these answers, we classified companies in the top and bottom 5 percent as talent magnets and talent laggards, respectively. Between those extremes, we created four intermediate levels, each accounting for 22.5 percent of respondents: low performers, average performers, high potentials, and high performers. Finally, we asked respondents to provide their company’s two-year revenue and profit growth.

This setup allowed us to assess these companies’ overall leadership and talent management capabilities and draw comparisons with other companies based on business performance. We were also able to isolate individual capabilities to see how they correlate with performance. Specifically, the index identifies which capabilities matter most at each level and which capabilities in particular will help companies move to the next level.

The study shows a correlation, not a causal relationship, between capabilities and business performance. Still, the findings are consistent with our observations at client companies, and we believe them to be directionally correct. Of course, context and judgment matter in defining a leadership and talent management strategy.

The power of the GLTI lies in its simplicity. It is a 20-question survey that places a company at one of six leadership and talent management capability levels and suggests ways to systematically move from one level to the next. It quantifies the revenue and profit gains that companies can expect from moving up the index. Here are the high-level findings:

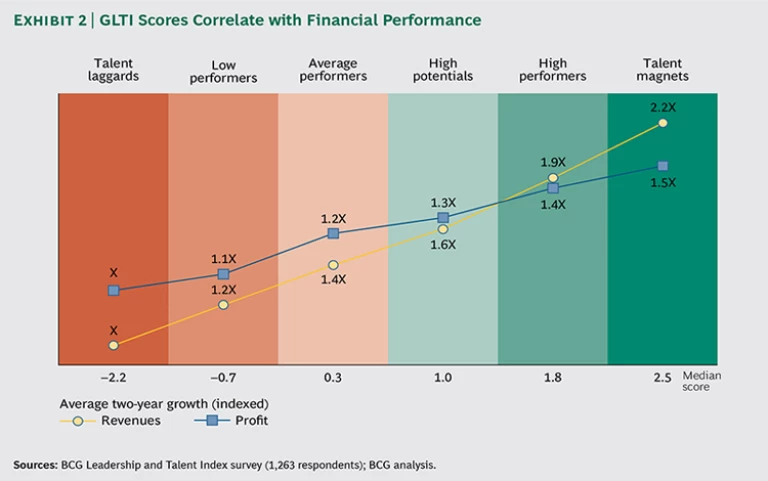

- Leadership and talent management capabilities have a surprisingly strong correlation with financial performance. “Talent magnets”—those companies that rated themselves strongest on 20 leadership and talent management capabilities—increased their revenues 2.2 times faster and their profits 1.5 times faster than “talent laggards,” or those companies that rated themselves the weakest.

- The performance spread on leadership and talent management capabilities was wide. The talent magnets had an average capability score of 2.5 (on a scale of –3 to 3), while the talent laggards had an average score of –2.2.

- Companies—even talent laggards—that move up just one level will experience a distinct, measurable, and meaningful business performance return.

For companies struggling to improve their leadership and talent management capabilities, or for those that want to reach the next level of excellence, the GLTI will lay out an improvement plan based on their starting position and existing capabilities, and it will anticipate gains in business performance as improvements are made.

Quantifying Leadership and Talent Management Capabilities

Companies rarely manage their talent as rigorously as they manage their balance sheet. This is in part because people development is hard to quantify. In order to put sharp edges around what is often considered a soft area, we divided leadership and talent management capabilities into six categories:

- Strategy: Planning leadership and talent needs over the short- and long-term, in line with the strategy and aspirations of the company; developing initiatives to meet those needs and tracking and measuring the initiatives

- Leadership and Talent Model: Defining clear leadership competencies specific to the company’s strategy and culture, and embedding those competencies in selection, development, promotion, and reward processes

- Talent Sourcing: Finding leaders and talent, both internally and externally; tailoring employer branding to specific talent pools; managing and developing successors effectively

- People Development: Systematically nurturing people by providing comprehensive and structured development opportunities, training, and tools

- Engagement: Fostering meritocracy and engagement throughout the company, especially among leaders and top talent

- Culture: Requiring top leaders to take responsibility for leadership and talent management by adhering to corporate values

The spread in these capabilities was wide, so we divided the companies according to six levels of performance to dig deeper. At either end, we grouped companies representing the top and bottom 5 percent of the pool: the talent magnets and the talent laggards. In the middle, we had four equally sized groups of companies: low performers, average performers, high potentials, and high performers. On average, the talent magnets had an average capability score of 2.5 (on a scale of –3 to 3), while the talent laggards had an average score of –2.2. (See Exhibit 1.)

The Value of Superior Leadership and Talent Management Capabilities

Companies with strong capabilities in leadership and talent management outperform those with weaker capabilities, as Exhibit 2 vividly illustrates. This is true across the entire spectrum of performance, not just at the extremes. At each successive level of performance, revenues and profits rose by an average of 15 to 20 percent and profits by 5 to 15 percent. This correlation is intuitive but had never previously been broken down and quantified.

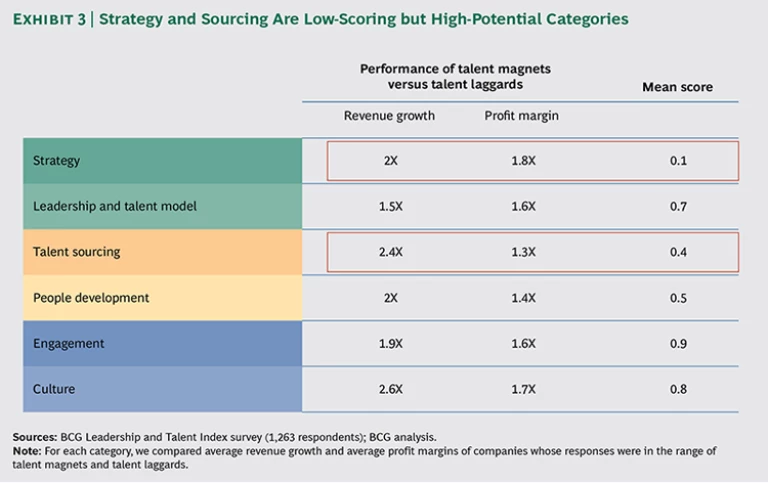

The strategy and talent sourcing categories had low overall capability scores, but the companies that got these capabilities right were handsomely rewarded. As illustrated in Exhibit 3, companies that scored in the range of talent magnets in the strategy category had twice the revenue growth of companies that scored in the range of talent laggards, and they had 1.8 times the profit growth. At the same time, strategy was the lowest-scoring category, suggesting that most companies have weak capabilities in this area.

Likewise, talent sourcing should be a priority. This is not simply about finding external candidates, which most respondents said their companies do well. It includes establishing transparent, efficient, and enterprise-wide talent management processes, developing a pipeline of successors, and tailoring an employer brand for specific talent pools. These are relatively weak capabilities at most companies.

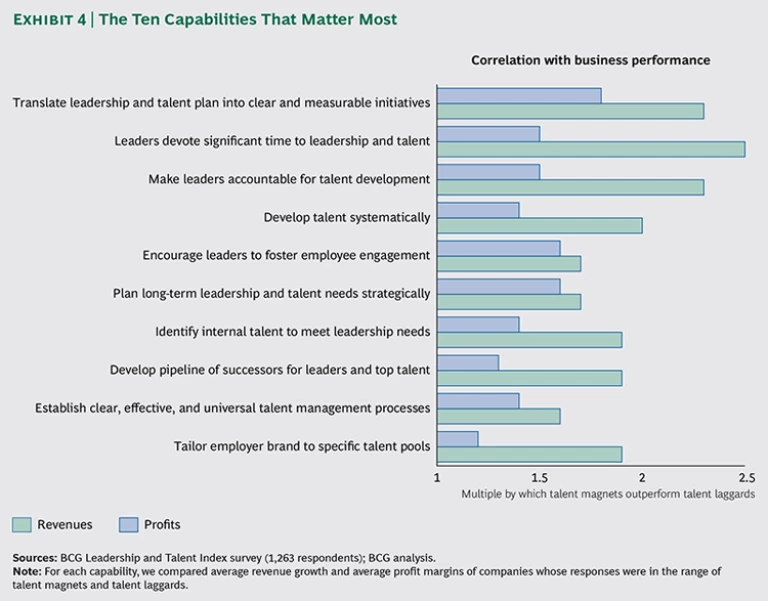

It turns out that ten capabilities correlate strongly with business performance. (See Exhibit 4.) Companies that are strong on these typically deliver strong business performance, too. The three capabilities with the greatest payoff all require the active participation of leaders: translating leadership and talent plans into clear and measurable initiatives, devoting significant time to leadership and talent management, and making leaders accountable for talent development.

The companies that excel at leadership and talent management have figured out how to involve their leaders, not just the HR team, meaningfully and regularly in people development. In fact, leaders at high-performing companies can spend more than 25 days a year on leadership and talent management activities.

Moving Up the Ranks

The GLTI allows a company to benchmark itself against the global database in order to get a sense of where it ranks and why. This provides visibility into the capabilities that it needs to improve and the potential benefit of improving them. As we will see in the next section, it also creates a company-specific agenda for becoming best in class on these capabilities.

For each level—talent laggard, low performer, average performer, and so on—the GLTI assesses how the capabilities of companies at the next level drive business performance. This analysis reveals the most important leadership and talent management capabilities that companies need to build in order to reach the next level. (See Exhibit 5.) Even more powerful, the GLTI can identify the most relevant capabilities for a company based on its specific leadership and talent management profile. Companies can thus follow a logical and structured path to achieve best in class.

That said, a few clear priorities emerge for companies at each capability level:

- Talent laggards need to fix the basics. An overall leadership and talent development culture is generally absent at these companies. They need to put in place a leadership model that clearly articulates the competencies that their leaders should demonstrate. In other words, they need to have a common language that describes the contributions and behaviors of leaders that are essential to the business strategy. Their senior leaders must focus on developing and grooming talent and putting in place leadership and talent management systems. These are important capabilities that must be continually nurtured. By fixing the basics, talent laggards can move ahead.

- Low performers need to cement the foundation. Low performers tend to have a leadership model in place, but it is not an integral part of their people processes. They need to embed the desired leadership competencies into recruiting, performance management, and reward systems and establish structured training and development programs to develop those competencies. Like talent laggards, they need to continually nurture a culture of people and leadership development.

- Average performers and high potentials need to sharpen strategy and talent sourcing and focus on long-term leadership development. At this level, companies generally have core leadership and talent processes and planning in place. To move ahead, they need to align their leadership and talent plan with their business strategy and actively measure and track progress. They need to pay special attention to sourcing talent externally by tailoring their employer brand to specific talent pools, and they need to identify and groom internal talent for future leadership roles. Culture is important at every step but especially at this level. Unless senior leaders demonstrate substantial commitment and ongoing support of these initiatives, the company is unlikely to become a high performer.

- High performers and talent magnets need to continually adapt themselves to changing leadership and talent needs. The companies with the strongest leaders and talent have long-range strategic processes and an ongoing commitment to such initiatives as corporate universities and leadership academies. Leadership and talent systems are not only fully embedded in the organization but also capable of evolving along with the changing needs of the business. These companies regularly conduct strategic workforce planning, succession planning, and talent diversity exercises.

While talent magnets are stronger in terms of each capability, what really sets them apart is their ability to be much more strategic in planning their leadership and talent needs and in defining specific and measurable follow-up initiatives. Leadership and talent management issues are on the senior executive agenda; leaders prioritize and spend time on these issues more than in other companies.

When Should You Use the Global Leadership and Talent Index?

The GLTI removes the guesswork in building leadership and talent management capabilities. Best of all, it is simple to administer. The short, 20-question survey will clarify not only the overall leadership and talent capability of a company but also a tailored agenda to improve.

The recommendations in the previous section are for the average or typical company within each category. The GLTI also enables individual companies, with their unique mix of capabilities, to precisely quantify their leadership and talent management capabilities and lay out an improvement plan that quantifies the value of making specific and targeted improvements.

Companies too often burn out on expensive leadership and talent investments that fail to deliver. The GLTI gives companies a structured step-by-step approach to developing stronger leaders, improving their overall talent profile—and ultimately their business performance and chances of success in strategy, transformation, and change.

For a company-specific assessment and tailored report, send an e-mail to GLTI_Support@bcg.com .