Large construction projects—including power plant and oil platform construction, civil and structural engineering, shipbuilding, and railway network construction and maintenance—are plagued by significant delays and cost overruns. Such problems are usually attributable to the increasing complexity of these projects as their size and technical challenges continue to grow. The result has been lower productivity and diminished profitability for many businesses involved in these projects, especially the general contractors that are responsible for project execution.

General contractors’ challenges in addressing the rising complexity of their operations stand in stark contrast to the successful efforts of leading manufacturers. Following Toyota’s innovative use of a lean approach to improve productivity in automotive manufacturing, many companies in discrete and process manufacturing industries have applied such an approach to manage complexity and secure step-change improvements in efficiency.

The time has come for general contractors to capture the benefits of applying a lean approach to project operations. The improvement opportunities are especially significant in the project realization phase, which includes engineering, procurement, and construction. General contractors applying a lean approach have reduced the time required to complete the project realization phase by up to 30 percent and reduced addressable costs by up to 15 percent, compared with the project’s initial plan, resulting in company-wide margin improvements of 2 to 3 percentage points. They have also improved quality and safety and, ultimately, accelerated the delivery of a completed project to the customer.

High Complexity Diminishes Productivity and Profitability

Unfortunately for businesses that undertake large construction projects, there is no shortage of examples that illustrate the need for taking action to address complexity. The problems that arose in the following three projects illustrate the scope and impact of the issues:

- A project to build a major European power plant was delayed by six months after a construction error led to a chemical leak. The error was attributed to several causes, including inadequate quality control, a lack of required materials, and subcontractors’ failure to adhere to the construction schedule. Because of the delay, the project’s cost increased by 20 percent—in addition to the operator’s losses stemming from the delayed opening of the plant.

- The completion of a cruise ship was delayed by more than six months because the shipbuilding company poorly managed the project from the start. Cruise ship construction is highly complex, requiring the participation of many suppliers and the use of many preassembled parts. Because the shipbuilding company had underestimated the project’s complexity during the planning phase, it was unable to effectively coordinate the scheduling and sequencing of work and the delivery of parts. The ship operator suffered significant losses. Because it had already fully booked the vessel starting from the planned delivery date, the operator had to pay refunds and other compensation to its customers, as well as endure unfavorable press coverage.

- The completion of a major office building was delayed by one year because the general contractor and a subcontractor had not agreed on which government approvals were required for starting structural work. Asserting that the appropriate building permit had not been obtained, the subcontractor stopped work for an extended period. The project also suffered from a lack of workflow coordination among subcontractors and from defective building materials, both of which caused overall project costs to almost double.

The complexity and uncertainty that underlie incidents like these result from the fact that site conditions, the nature and scope of the work, and the identity and combination of participants often vary significantly among projects. To illustrate the distinction between a conventional manufacturing environment and a large construction project, consider the way that work flows through an automotive assembly line, compared with a construction site. On an assembly line, the vehicle being built flows through stationary work areas. At a construction site, in contrast, subcontractors and craftspeople move around the site, and different organizations and people are present depending on the stage of the project. This variability—combined with longer time frames, more interdependencies, and greater complexity of individual processes and of the entire project—makes the sequencing of work much more complicated.

These distinctive characteristics of construction projects are reflected in the product itself, the associated processes, and the people involved:

- Product. The size and costs of large projects have grown markedly in recent decades. Technical challenges have increased, because project managers must apply new technologies to construction projects. In addition, these managers must install more complex, frequently interlinked, technologies in the project. Large projects also more often entail a high degree of customization to satisfy clients’ requirements.

- Processes. Delivering a more complex project requires managing a larger organization, a greater number of subcontractors, and a more diverse set of stakeholders, including joint venture partners. Contractors also must manage a higher level of volatility in the supply chain and more numerous and stringent regulatory requirements. Adding to the challenges, specifications are often unclear at the beginning of the project or clients may change the specifications after work has started.

- People. Managing complex projects successfully requires a high degree of collaboration and communication among people from various organizations, including the owner, architect, engineering company, general contractor, subcontractors, and equipment suppliers. Understanding the capabilities required for the project and finding the right organizations and people to provide them is challenging. Once on-site, this constellation of participants, many of whom have never collaborated before, must ramp up their work immediately. To coordinate these participants effectively, a contractor must schedule and sequence their work and require strict adherence to process standards and KPIs. The systematic transfer of knowledge within and among the various organizations is also essential.

Complexity and uncertainty can significantly diminish the productivity and profitability of all types of large projects. A

Using a Lean Approach to Capture Value

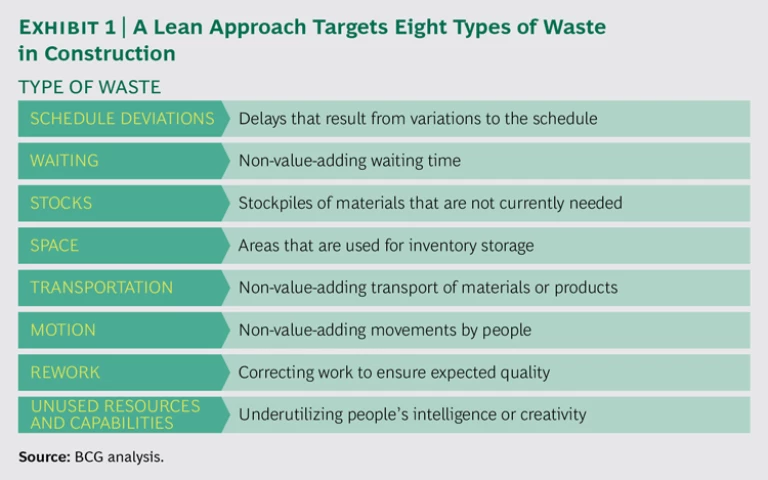

A lean approach reduces complexity and uncertainty by eliminating waste and non-value-adding activities throughout an entire process or value chain. The distinctive characteristics of construction projects give rise to particular types of waste and non-value-adding activities. (See Exhibit 1.) By revealing and removing them, a lean approach makes processes more stable, predictable, and efficient—all of which increase productivity and help general contractors achieve targets for profitability. The goal is to focus the organization on activities that create the greatest value—whether the highest quality, the lowest cost, or the shortest lead time—for the customer.

A lean approach has helped companies in a wide variety of manufacturing industries capture productivity improvements. These industries include auto manufacturing and other discrete manufacturing industries (such as aircraft, machinery, and equipment), as well as process manufacturing industries (such as chemicals, biofuels, and steel). For example, chemical manufacturers have used a lean approach to improve the productivity of their processes by 5 to 7 percent. Large construction businesses can likewise address their complexity challenges by applying a lean approach, although they will need to adapt it to the distinctive challenges of construction work.

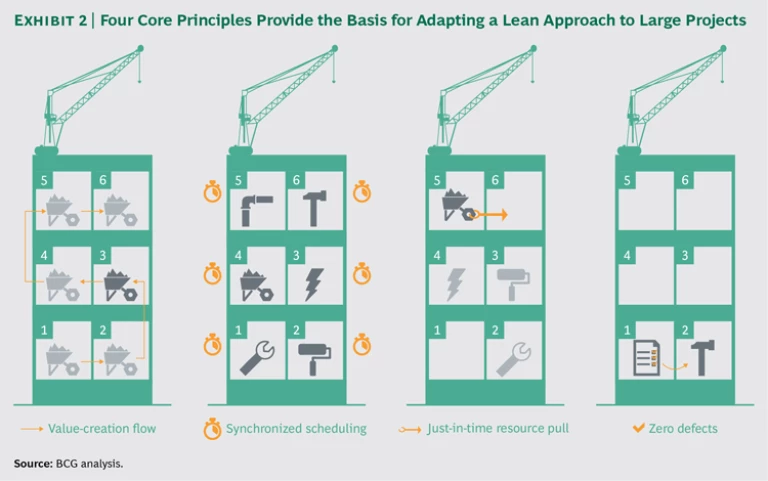

Four core lean principles form the foundation for adapting a lean approach to reduce complexity and uncertainty relating to construction projects. (See Exhibit 2.)

- Value-Creation Flow. To ensure that activities are focused on value creation, all resources, materials, and information need to be interlinked in a single flow through the project. The goal is to eliminate downtime and ensure that value-adding activities occur continually, thereby shortening the project’s overall timeline. To introduce this principle for a recent construction project, The Boston Consulting Group divided the building into several sections and worked with the contractor to design a value-creation flow on the basis of the movement of subcontractors and craftspeople through each section.

- Synchronized Scheduling. Contractors using the lean approach establish a standard takt—that is, the maximum completion time allowed—for an operation within a recurring process, such as each step required to install electrical wiring in each section of a building. The takt in construction typically ranges from one day to one week. To reveal and help reduce production bottlenecks, contractors apply a takt analysis to develop a synchronized and repeating operating rhythm, with tight scheduling. At project sites, scheduling equipment and personnel on the basis of takt ensures that all subcontractors and operators are aware of the time they have to complete an operation so that they can work together smoothly. A team comprising the general contractor, subcontractors, and, ideally, suppliers should jointly determine the takt before work commences.

- Just-in-Time Resource Pull. In a lean operation, resources and materials are pulled into the process just in time to satisfy project requirements. The just-in-time approach allows contractors to eliminate waiting times, avoid storing materials, and reduce costs for stock. This approach also promotes flexibility by allowing contractors to accommodate their clients’ last-minute decisions. To avoid delays and higher costs, however, this approach must be carefully managed on the basis of lead times for each resource and the various materials. In supporting project management for the construction of a cruise ship, BCG worked with the shipbuilding company to demarcate “frozen zones”—periods during which the shipowner could not change the type or specifications of materials to be ordered. The shipowner was required to communicate the specifications for the various materials to the shipbuilding company before the frozen zones, so that it could place orders with sufficient lead time to adhere to the agreed-upon schedule and budget.

- Zero Defects. Through continuous improvements fostered by control and feedback mechanisms, contractors can strive to come as close as possible to achieving the goal of zero defects and thereby standardize and stabilize processes. Short-cycle processes can be deployed throughout the project value chain to significantly reduce the number of defects. Such processes allow project managers to detect mistakes quickly, so that they can remediate the errors and prevent them from recurring in subsequent work at the site. Catching defects early is especially important with regard to repeated elements and processes, which may recur dozens or even hundreds of times in any given project.

Optimizing the Value Chain

The four core lean principles provide the basis for adapting a lean approach to promote efficiency and improve productivity and profitability during each phase of a project’s value chain: tendering, project realization, and commissioning.

- Tendering. In this phase, contractors should focus their efforts on projects that offer the greatest potential value. The dimensions to consider when evaluating a project include the likelihood of its being realized, the probability of winning the tender, the organization’s capacity to execute the project properly, the risks associated with the project, and the profiles and experience of the potential project team. When contractors pursue all available tenders, they typically waste resources by competing for projects that they could not complete profitably or that they do not have a realistic chance of winning.

- Project Realization. During this phase, a lean approach eliminates non-value- added activities in engineering, procurement, and construction, a goal that entails both planning and execution. Excellence in planning is essential to establish the prerequisites, such as processes and schedules, for achieving the objectives of lean execution. The potential to capture value is high in this phase.

- Commissioning. Here, the objective is to implement lean operations for maintenance and service. To enable this, efficient maintenance and servicing at minimal cost should be key design criteria when planning the project.

Focusing on the Project Realization Phase

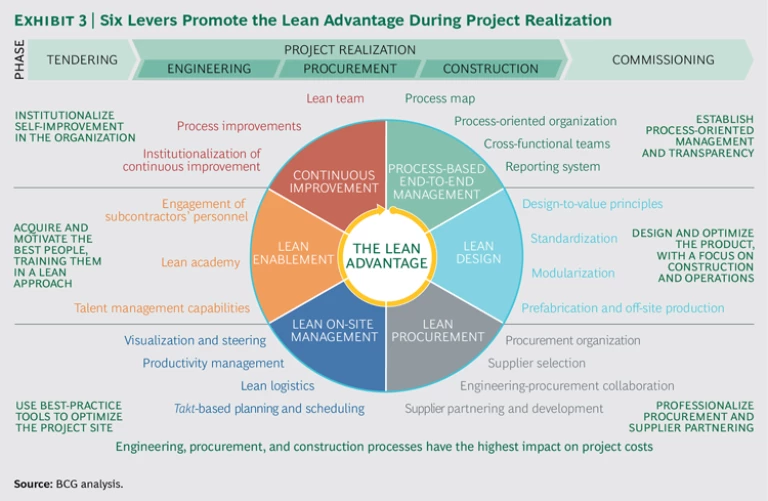

Given the high potential to capture value during the project realization phase, we focus on the six lean levers, each of which applies some or all of the four core lean principles and is intended to reduce complexity and uncertainty relating to products, processes, or people, or a combination of them. (See Exhibit 3.) Contractors should institutionalize the best practices described for each of these levers in a lean construction system that sets out both the organizational and technological requirements for executing a project. This system should then be used on a company-wide basis to guide the execution of future projects.

Process-Based End-to-End Management. To successfully deploy a lean approach, general contractors need to foster cross-functional cooperation across the engineering, procurement, and construction functions. By mapping processes from end to end, contractors can identify sequential dependencies, synchronize subprocesses, and efficiently allocate resources. A process map provides the basis for establishing cross-functional teams so that employees work across organizational silos to jointly own the end-to-end process. The map also encourages employees to think about how their individual work relates to the overall process.

Contractors need to apply the right set of controls to ensure that processes operate efficiently. The frontloading of work and short-cycle processes allow contractors to intervene early when problems arise and ensure that the most qualified employees get involved in a process at the right time. These controls make it easier for managers to correct mistakes before serious consequences result and to keep costs low over time. Comprehensive reporting systems provide relevant information to the appropriate decision makers when they need it and help them identify issues requiring action at each organizational level. Status tracking—updated daily, weekly, biweekly, or monthly—provides the basis for successful project steering by allowing contractors to monitor scheduling, quality, and commitment (for example, subcontractors’ participation in steering sessions).

Lean Design. In the engineering phase, projects should be designed to promote efficiency in operations and construction. Contractors should apply design-to-value principles to reduce total costs. Efficiency is also increased through the standardization and modularization of parts and segments. Prefabrication and off-site production can be used to shorten the project completion time, reduce costs, and improve safety.

Lean Procurement. Establishing a dedicated procurement organization to professionalize procurement and supplier relationships is crucial for capturing lean advantages. Expenditures for each purchasing category should be clearly understood, so that the organization can prioritize efforts to optimize procurement. Contractors should focus on identifying and selecting suppliers on the basis of their capabilities to meet project objectives. Suppliers’ pricing models and performance metrics are additional indicators. Contractors should also regularly review the performance of current suppliers and pursue opportunities to develop their capabilities and form strategic partnerships with them. In addition, fostering effective collaboration between procurement and engineering during the planning stage is critical to achieve lean objectives. The procurement organization should work with engineers to identify equipment requirements in the project’s critical path, obtain technical information from equipment suppliers, and define the subcontracting strategy on the basis of suppliers’ capabilities and costs.

Lean On-Site Management. During construction, contractors should create a single value-added flow by optimizing the overall process rather than by seeking to optimize the performance of each function. Bringing various subcontractors and subprocesses into the flow requires coordinating the speed at which subcontractors work and creating interfaces that enable smooth handoffs. A takt-based approach to synchronized scheduling helps to coordinate the subcontractors and teams working on different sections of the project and reduces idle times.

Applying a lean approach to logistics is critical to promote a stable flow of materials to the site by ensuring that they are pulled into the process at the right place and time and in the right amount. For example, the correct amount of materials for drywall construction would be delivered directly to a designated area within a building section once per takt. This approach minimizes the need to store materials at the site while also preventing disruptions and bottlenecks that could result if materials were unavailable. To achieve these goals, contractors should determine the scheduling requirements, including lead times and frozen zones, for the entire supply chain—starting at the site and going back to the manufacturer. Contractors should also establish quality gates along the supply chain and proactively identify potential issues long before materials are actually required at the site.

Deploying short-cycle processes during construction is crucial for continuously measuring and tracking schedule adherence and identifying problems before they can endanger the project’s on-time completion. The schedule adherence of each process cycle should be frequently monitored, ideally on a daily basis, and reported as either on track or requiring action. Visualization of all relevant information regarding the construction project is crucial to foster communication about the schedule and plan. For example, team communication boards showing the status of KPIs for scheduling, quality, and commitment can enable teams to discuss all relevant steps on a regular basis, track progress, and stay informed about the common goals.

Lean Enablement. Contractors need to put in place the right enablers to ensure that their workforce can apply a lean approach. Strong talent-management capabilities are essential for recruiting and retaining employees who have the skills required for implementing a lean approach. Contractors should focus on motivating and training both current and new employees and instill a deep understanding of lean principles throughout the organization. A customized lean academy can be created to provide training on-site, thereby allowing personnel to see the benefits directly related to their own work. The lean curriculum should be customized to provide content targeted to people at each organizational level, such as project directors or foremen. Given that subcontractors perform a significant amount of the work, their personnel should be included in the training programs. Contractors should also apply a “train the trainers” approach by educating a selected group of employees who will serve as trainers for their colleagues. A schedule for training programs should be established and adhered to.

Continuous Improvement. Contractors should institutionalize continuous improvement organization-wide. By conducting an analysis of current weaknesses, contractors can gather a fact base for creating a plan to implement prioritized process improvements and new standards. A dedicated organizational unit—the lean team—should be established, with a mandate to continuously build lean capabilities in the organization and foster a culture that embraces the pursuit of continuous improvements. The unit’s staff should work with employees on-site and in workshops to implement process improvements and standards.

We present case examples to illustrate the application and impact of selected levers. (See “The Lean Levers in Action.”)

THE LEAN LEVERS IN ACTION

Examples relating to four levers help to illustrate how businesses can apply a lean approach to promote improvements during the project realization phase.

Process-Based End-to-End Management. A shipbuilding company applied this lever to reduce the time required to complete a project by 15 percent and cut total costs by 5 percent, compared with the initial plan.

To enable end-to-end management, the company set up a central control room (called a “big room” in lean terminology) and established project-steering routines. The room served as the venue for daily and weekly meetings to discuss the project’s progress and to track KPIs. These discussions allowed a cross-functional management team to identify deviations from the project’s plan relating to the schedule, quality, and subcontractors’ commitments. To address these deviations, managers defined specific actions, identified the responsible party, and set the time frame for completion. The management team planned and coordinated different elements of the project by defining takt, identifying repeatable elements, and organizing materials, drawings, and work instructions for the end-to-end process.

Lean Design. A railway construction company experienced major delays at the start of a project because the civil-engineering work was not completed on schedule. To compensate for the lost time and meet the deadline for completion, the company opted to redesign several elements of the construction project so that it could use standardized and modularized parts for rails, base plates, and concrete. These parts could be prefabricated off-site, which reduced production costs and increased safety and quality. On the downside, however, the company incurred higher costs to transport the prefabricated products. Despite the trade-off in costs, the off-site production of these parts enabled the company to reduce the lead time for installation and finish the project before the planned completion date—more than compensating for the earlier delay.

Lean On-Site Management. During a civil-engineering project, a contractor applied this lever to reduce the cycle time of a recurring tube-changing process by up to 67 percent. Creating a visualization of the process steps enabled the contractor to identify and eliminate unnecessary steps and bottlenecks. The contractor applied these insights to rearrange the work area for the process, which allowed employees to perform several steps simultaneously and complete each step in less time. Moreover, safety improved, because enabling each employee to work in a well-defined zone limited the need for movement. These improvements not only allowed the team to complete the overall process faster, but also reduced the required staffing capacity by 25 percent. The impact was especially significant given that the team performed the tube-changing process an additional 5,000 times after it was optimized.

The civil-engineering contractor also optimized the process of transferring the construction work to different locations over the course of the project, thereby reducing the time required to complete each transfer process from 14 days to 8. Although transferring the construction work entailed the same steps in each case, the contractor needed to adapt the process to each site’s individual characteristics. The contractor identified and set out details for general levers that could be adapted to optimize the transfer process for each site. The contractor also established regular meetings in which team members could discuss adapting the optimization levers for each transfer of the work.

Lean Enablement. A structural-engineering company selected several employees to serve as trainers who would guide and support the implementation of a lean approach at its project sites. The company educated these trainers on the main principles of lean (such as waste and value, takt planning, and zero defects). The trainers then participated in developing a training curriculum for other employees as well as a program that simulates the use of a lean approach on-site.

The initial phase of the simulation showed employees the number and types of disruptions that occur during a traditional project, how these disruptions affect quality, and the resulting costs to the project. In subsequent phases, employees learned how they could apply lean principles to improve project execution and quality. The first projects to implement the training program have reduced construction time by up to 12 percent and captured savings of up to 5 percent, compared with the initial plan.

Determining the Starting Point

In recent years, many general contractors have undertaken small-scale efforts to apply a lean approach and have achieved some degree of success. However, a large-scale rollout should be preceded by a structured pilot program at one project. A well-designed pilot enables the organization to test the application of a lean approach under real-world conditions, validate the approach, and achieve initial results that will demonstrate the benefits to employees and other project participants. Contractors that have successfully tested a lean approach can then seek to establish a full-fledged lean construction system to use across all of their projects.

Contractors can choose one or more of four approaches to launching a lean program, each of which should be tested at one project before a company-wide implementation. The right combination of approaches depends on the contractor’s experience in applying a lean approach and motivation to capture improvements:

- Lean Health Check. Contractors in the early stages of learning about the lean approach can use a “health check” to identify the main areas for improvement, prioritize the issues to address, and estimate the improvement potential. (See “Using a Lean Health Check to Assess Performance.”)

USING A LEAN HEALTH CHECK TO ASSESS PERFORMANCE

General contractors can use a lean “health check” to assess their current performance for each of the six levers applied during the project realization phase. An effective health check requires experience in identifying waste in site operations and then benchmarking the results to gauge relative performance. Contractors typically conduct the health check at one project or in one organizational unit and then extrapolate the results to the broader organization.

For each lever, a contractor should consider a set of questions and related analyses. The following are examples of high-level questions, which should be adjusted and expanded on the basis of an organization’s specific needs:

- Is a takt-based, synchronized scheduling approach applied to coordinate the subcontractors and teams working on different sections of the project and to reduce idle times?

- Are controls, such as frontloading work and short-cycle processes, used to catch problems early?

- To what extent are standardization, modularization, prefabrication, and off-site production used to improve efficiency and productivity?

The assessment, which can usually be completed in two to three weeks, shows the strengths and weaknesses of a contractor’s lean performance, benchmarked relative to competitors, and pinpoints the best areas to target for an initial improvement effort. The exhibit below shows sample results of a comparison of a company’s current performance with industry best practices.

Contractors can use the results of the health check to estimate the potential cost savings and revenue increases from process improvements. The health check can form the basis for either a subsequent in-depth review of lean performance (for example, to identify the root causes of deficiencies) or a lean project in which specific lean measures are designed and implemented to improve productivity and profitability.

- Lean Training. Contractors that have not yet put their lean knowledge into action can benefit from a multiday training program. In addition to helping participants understand theoretical principles, an effective program will include simulations that allow attendees to actively experience how using a lean approach can improve the performance of projects.

- Lean Project. Contractors can apply the six lean levers discussed earlier to a specific project in order to achieve gains in productivity and profitability. Contractors can launch this effort when planning a project or to support the turnaround of a project that has encountered issues during construction.

- Lean Team. Contractors with lean experience that are highly motivated to capture the full lean advantage are ready to establish a lean team to move the effort forward, ideally in combination with launching a lean project. Establishing a permanent lean team is essential for all contractors that seek to anchor lean thinking in their operations sustainably over the long term.

General contractors that don’t join the initial wave of companies realizing the lean advantage risk falling permanently behind the leaders in their increasingly competitive markets. Contractors that capture the lean advantage will set new standards for project quality, costs, and delivery time during the next few years. In doing so, they will establish a decisive and sustainable competitive edge that allows them to build enduring business relationships with project operators in the public and private sectors.