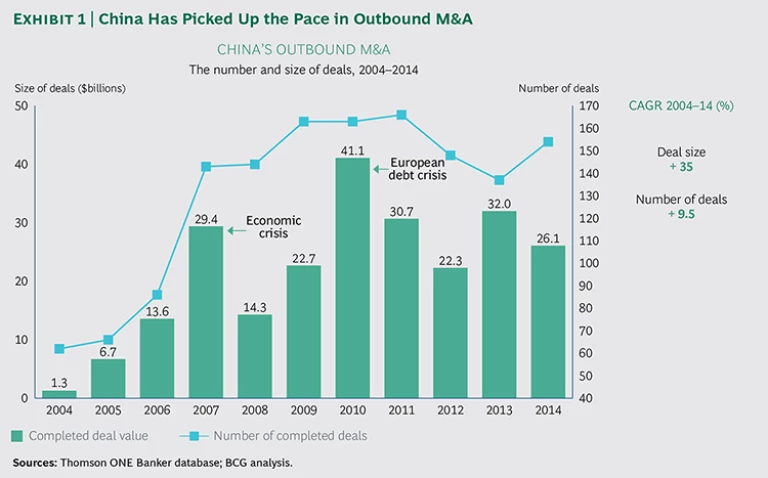

At first glance, Chinese companies would appear to be enjoying a golden age of deal making: the outbound M&A market flourished from 2004 through 2014, with deal value growing at a compound annual rate of as much as 35 percent, and deal volume expanding at a compound annual rate of 9.5 percent. In 2014 alone, Chinese companies made 154 outbound M&A deals, with a total deal value of $26.1 billion. (See Exhibit 1.)

But the impressive growth numbers mask some less impressive statistics. Chinese acquirers complete just 67 percent of their outbound deals, on average, far fewer than those completed by European, Japanese, and U.S. outbound acquirers. What’s causing so many deals to fail? The main culprits, according to our research, are flawed, unclear M&A strategies and ineffective deal management. Even deals that are completed often fail to achieve their goals because of poorly planned and executed postmerger integration and synergy capture.

Failed deals represent enormous missed opportunities. Chinese acquirers have never been better positioned to take their place among the top ranks of global deal makers. But before they can do so, they must commit themselves to investing heavily in the skills, capabilities, and—most important—the seasoned international talent required for M&A activity on the global stage. And they must act now, while the macroeconomic currents worldwide continue to flow strongly in their favor.

In this report, we review the confluence of trends, developments, and policy prescriptions that have contributed to the surge in outbound Chinese M&A. We examine the dynamics that are changing the game for Chinese acquirers and analyze why so many outbound deals fall through—and why so many of those that are completed yield disappointing results.

What’s Driving China’s Outbound M&A

A host of internal and external developments have converged to produce the growth in outbound M&A. Within China, looser economic policies and a rising private sector have spurred companies to take a page from their foreign competitors’ playbooks and seek overseas expansion via outbound M&A. Globally, as China has emerged as a leading international economic power, an increasing number of foreign sellers in developed markets have come to see the advantages of working with Chinese companies. In addition, the Eurozone debt crisis has presented Chinese acquirers with a prime opportunity to snap up European companies at bargain prices. The slowing of the European economy in the wake of the global financial crisis, meanwhile, has produced an attractive external-investment environment of renewed economic growth and relatively low asset valuations.

What’s more, the economies of the U.S. and Western Europe are strengthening just as economic growth in China is decelerating, a development that bolsters the case for outbound deal making by Chinese companies. Companies in the developed world have a long and successful record of using M&A to cushion themselves against economic fluctuations in their home markets. The steady growth that these companies have achieved amid domestic economic volatility is vivid and convincing testimony of the value-creating power of strategically grounded, well-executed outbound M&A.

A New Set of Targets for Chinese Acquirers

Historically, China’s outbound M&A activity has targeted mostly energy and resources companies, with the aim of ensuring the smooth operation of the national economy and Chinese enterprises and hedging against big swings in commodity prices. From 1990 through 2014, the energy and resources sector accounted for the largest portion of outbound M&A, constituting more than 40 percent of overall outbound M&A deal value.

Thanks to their robust strength and talent, China’s top 500 companies have been active players in outbound M&A deal making. They have accounted for 65 percent of outbound deal value and 30 percent of the 873 deals completed in the past five years.

We recently surveyed 33 Chinese companies actively pursuing outbound M&A and found that 90 percent of respondents had established a dedicated function for M&A activities. A large majority of companies stated that they have the required capabilities for outbound M&A, including an explicit M&A strategy; the proper organizational structure, talent, work flow, and tools; effective governance; and a system for monitoring and evaluating deal performance. Moreover, 60 percent of respondents felt that they had gained expertise in postmerger integration (PMI). However, the continuing challenges that many Chinese acquirers have encountered in the international deal-making marketplace suggest that many companies may have overestimated their readiness to compete on equal terms against seasoned developed-world players.

Companies need all the expertise they can develop, because the Chinese government has been encouraging outbound M&A since the outbreak of the global financial crisis in 2008. This policy is part of what the government envisions as a new era of overseas investment. President Xi Jinping said at the 2014 APEC leaders’ summit that China’s outbound investment will nearly triple, to $1.25 trillion, over the subsequent decade. This massive surge will reshape the global investment landscape and create ample opportunities for a new wave of outbound M&A.

In response to these shifting forces, China’s government has worked to facilitate outbound M&A. In March 2014, the Chinese government issued a set of new policies and procedures that simplify the foreign-exchange management scheme for outbound M&A and substantially relax restrictions on the power to authorize outbound M&A projects.

The Motivations for Outbound Deals Are Changing

As China continues to internationalize, the focus and intent of outbound M&A activities are shifting. Our research reveals that, in contrast to the long-term historical trend, only 20 percent of outbound M&A deals made during the past five years had the goal of acquiring strategic resources, while roughly 75 percent were aimed at accessing technology, brands, and market share. Previously, most of China’s outbound M&A players were state-owned enterprises seeking resources. Today, however, a growing number of private-sector deal makers are looking to gain market share and enhance their core capabilities. Rather than simply locking in supplies of key resources, Chinese companies are engaging in outbound M&A to access new profit pools, capture new markets, and tap the skills of globally competitive leaders. Acquirers also view outbound M&A as a way to obtain cutting-edge technology as well as brand and management experience in overseas markets.

In keeping with the change in the motivations for M&A, the volume of energy and resources deals has declined, while the volume of deals in industrial goods; consumer goods; finance; and technology, media, and telecommunications has increased. The relatively low completion rate, however, has remained more or less constant. These developments suggest that Chinese companies in many industries urgently need to improve their outbound M&A skills to better address the challenges of globalization and to achieve more successful deal outcomes. They need to raise their games in due diligence and PMI and apply the lessons learned from previous deals.

As Chinese Acquirers Enter New Hunting Grounds, Challenges Arise

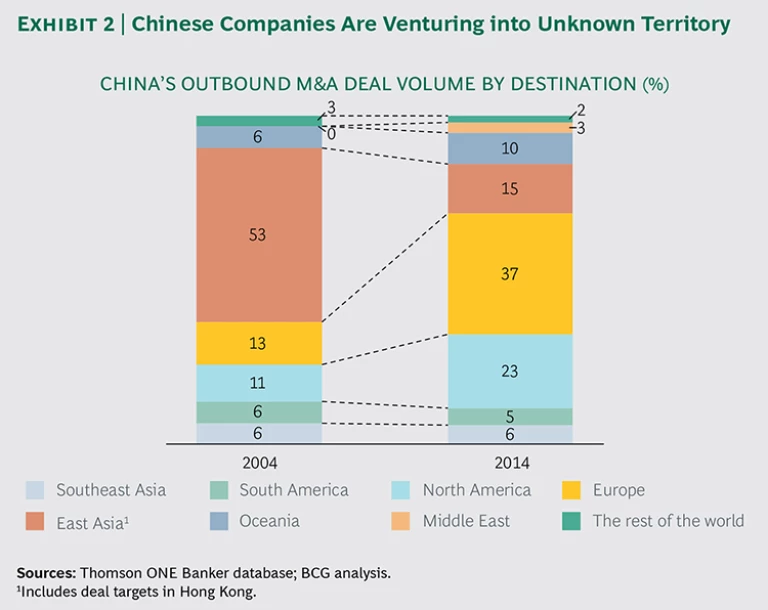

During the past few years, Europe and North America have surpassed Asia as the most sought-after targets for outbound M&A, accounting for roughly 60 percent of outbound M&A deals by Chinese companies in 2014. (See Exhibit 2.) By contrast, the number of deals targeting traditional destinations, such as East Asia, has plummeted. Given the wide disparities in language, management style, and corporate culture between European and U.S. companies versus Chinese companies, the westernizing of outbound M&A destinations presents new challenges for Chinese buyers.

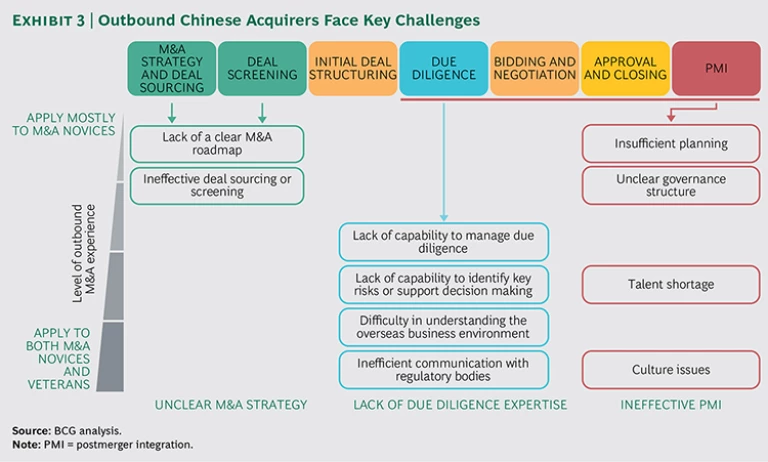

We have identified the greatest of those challenges, drawing on our analysis of outbound M&A deals during the past decade and our observations of evolving trends in the field. As we suggested earlier, these challenges center on M&A strategy, due diligence, and PMI—the fundamentals of effective deal management. (See Exhibit 3.)

M&A strategy is often unclear. BCG’s survey indicates that many companies lack a clear M&A roadmap, have only a vague idea of the purpose of any given deal, and know little about the value of possible synergies or how to capture them. Some Chinese companies blindly launch bids overseas without sufficient preparation in pursuit of quick success and scale expansion; others fail to draw up a realistic outbound M&A timeline before they venture into the international M&A arena.

The absence of any discernible M&A strategy has hampered more than one company’s globalization drive. Time after time, we have observed Chinese companies with well-respected, widely recognized brands in their home market launch bids for overseas companies with very little consideration of how well the targets fit with the acquirers’ overall strategies. As a result, these companies are unable to define how a combined entity would operate or identify opportunities to capture revenue and cost synergies.

Due diligence is often incomplete and fails to quantify risks. Sometimes, Chinese companies’ due-diligence teams face challenges, such as a lack of experience with internationalization; insufficient knowledge of overseas commercial and legal environments or profitability models; a limited ability to organize and coordinate commercial, legal, financial, and HR due diligence; and incapacity to assess, identify, and evaluate risk points in the due diligence process.

These shortcomings often become apparent when a Chinese company finds itself bidding against a global rival to acquire a target operating in the developed world. The Chinese company may not recognize the urgency of putting together a detailed bid and PMI plan, putting it at a market disadvantage when preparing a timely, realistic bid. Compounding the problem, lengthy and cumbersome internal-approvals processes may hamper the company in assembling a team of professional advisors to assist with the specifics of the bid.

What’s more, Chinese acquirers often fail to anticipate how a rival bidder might counter or deflect their overtures to a target. As a result, rapid changes in the deal environment can leave a Chinese company flat-footed at precisely the moment when it needs to act quickly. Unable to pivot quickly to a new bidding strategy—a plan B—when the deal environment changes, the company may be unable to set priorities for accelerating its due-diligence process and thus may miss the deadline for submitting a second counteroffer.

Problems may also arise when decision-making power is highly concentrated at headquarters. In that case, the due diligence team in the field may be left without sufficient power to make necessary judgments and decisions in real time, rendering it all but impossible for the would-be Chinese acquirer to keep up with the fast pace of deal making in the developed world or to react quickly enough to changing deal conditions. The company’s negotiating strategy is therefore handicapped by senior leadership’s insistence in making all the decisions for the deal. That can lead to delays in negotiations and frustrate the company’s negotiating team, whose members are usually much closer to the action and more familiar with changes in the deal environment. Compounding the difficulty, senior leadership might turn a deaf ear to the company’s local advisors, using them only to prepare deal documents and scorning any attempt to offer professional judgments about local market and business practices.

Highly centralized decision-making processes can also inhibit local teams from speaking up at crucial moments. Lacking a forum in which they can share their views of the deal with senior management, they can only look at one another and wonder who has the authority to act when an on-the-spot decision is required. A lack of clear and consistent processes explains why so many teams return to China empty-handed.

PMI Proves to Be Difficult to Master

Shortcomings in due diligence should not be overstated. After all, Chinese acquirers do complete more than two-thirds of the deals they pursue. Still, those deals aren’t always successful. We have observed that some Chinese buyers, especially those whose targets are leading players in developed countries, do not have a clear, detailed plan for integrating an acquisition, merging operations, and capturing cost synergies. Acquirers themselves confirm our observation: according to a recent survey by BCG, Chinese acquirers reported that only 32 percent of their outbound deals were trouble-free. During our casework with Chinese clients, we have observed several common characteristics of suboptimal PMI.

PMI plans lack adequate detail. Some acquirers impede their own PMI efforts because they fail to think through the integration process in adequate detail. As a result, the acquirer and the target are unable to align on cost and revenue synergies or to share best practices on topics such as promotions, product mix, and supply chains. Without such an alignment, sales efforts can quickly descend into chaos, with each side dumping its best-selling items into the other’s sales channels. Responsibility for rationalizing product lines is diffuse, resulting in a lack of accountability—a situation that is often aggravated by the absence of defined financial targets and KPIs.

At the root of such deficiencies is the acquirer’s failure to develop a clear, coherent plan for the new entity’s people and organizational structure in advance of the closing. Reporting lines are unclear and inconsistent, and poorly defined roles and responsibilities often all but paralyze the combined organization. These shortcomings are exacerbated by inadequately delineated geographic operating boundaries, which result in sales teams from both sides chasing the same set of customers without regard to local brand and product preferences.

Measuring the success, or lack thereof, of such mergers is nearly impossible, especially if the two organizations are slow to integrate their IT operations. In such cases, the acquirer’s senior managers will have trouble evaluating their progress toward merger goals and gaining visibility into supply chains, adding to the difficulty of eliminating overlaps and realizing cost synergies.

Culture clashes cripple execution. Cultural differences can also impede effective PMI. While more experienced acquirers are careful to identify key talent during the due diligence phase, Chinese acquirers leave due diligence to a handful of managers who are often already occupied with at least one other acquisition. As a result, they do not have the time or resources to either identify key talent for retention or get a feel for the culture of the target company.

These drawbacks can leave Chinese companies inadequately prepared for the post-transaction phase. While a more experienced acquirer might assemble a team of 50 or more executives with global experience to lead the acquired company during the crucial first few months following closing, Chinese acquirers might send in a small team of senior executives to handle the management handover, expecting them to do the work of the dozens of managers they have replaced.

The absence of a coherent, detailed plan for managing people can impede PMI efforts in other ways as well. Lacking experience with unionized workforces, Chinese managers sometimes neglect to form relationships and maintain communications with employee representatives. As a result, employees may feel slighted and believe that their corporate culture is under threat. They may become alienated from the Chinese executives who replace their long-time managers and bridle at attempts to impose a top-down, authoritarian culture onto a formerly egalitarian organization.

Such tensions may be heightened if an acquirer reneges on promises such as assuring the continuous employment of all employees of the acquired company, developing a mid- to long-term development plan, or laying out a roadmap for R&D investment, new product launches, or brand-building. Broken pledges can damage employees’ trust in management beyond repair.

Other common PMI pitfalls include a failure to adequately define an overseas corporate governance structure that would enable the acquirer to effectively steer its acquisition. Staff members at the headquarters of many Chinese companies effectively play the role of portfolio managers, setting only high-level targets for subsidiaries and granting them operating and functional autonomy. Companies in the developed world, by contrast, are often highly centralized, with headquarters managing the sales, marketing, R&D, and planning functions, while the subsidiaries handle only manufacturing.

Because decentralized organizational structures leave so much distance between headquarters and business units, headquarters may find itself with no means for offering input into the strategy or governance of its acquisition. Such governance shortcomings often result in missed synergy targets and hamper efforts to craft plans for improvement.

How Successful Acquirers Do It

Amid this generally dismal backdrop, a few success stories stand out sharply. They suggest that the secret of successful Chinese acquirers is no secret at all. Rather, those acquirers demonstrate the power of rigorous strategy, crisp execution, effective governance, operational discipline, and well-executed PMI.

Lenovo Group. Lenovo’s experience is an example of how using a precise M&A strategy and conducting sophisticated due diligence can produce spectacular results. The company’s deep understanding and robust assessment of its target, IBM’s personal computer (PC) segment, enabled Lenovo to develop into a respected market leader after the acquisition.

The path toward that deal began in 2003, when Lenovo formulated its strategy to focus on PCs and go global. The search for a suitable target began almost immediately thereafter, culminating in the decision, in 2004, to acquire and integrate IBM’s PC business. Although observers likened Lenovo to “a snake trying to swallow an elephant,” a common Chinese saying, the company achieved a compound annual growth rate of 41 percent during the subsequent decade.

Why was the transition to new ownership so smooth and successful? One key reason was that Lenovo went into the deal with a clear, strong M&A rationale at the ready. At the start, after the company had set its strategic objective, Lenovo launched a worldwide search for potential acquisitions. When the company set its sights on IBM’s PC business, the due diligence team swung into action, performing a deep-dive analysis of Lenovo’s potential synergies with IBM’s PC business. On the basis of considerable benefits identified in brand proposition, market channel, technology R&D, HR, and cost structure, Lenovo moved nimbly, aggressively, and decisively to claim its prize.

Mindray Medical International. Chinese companies can also rapidly build their deal-execution capabilities by tapping experienced advisors—and learning from their experience. That’s the course that Mindray took when it launched an ambitious program to acquire leading specialty producers of medical devices in developed markets. Its acquisition of the patient-monitoring unit of U.S.-based Datascope in 2008 is an example of what Chinese acquirers can accomplish when they consciously determine to fast-track the development of transactional excellence in a planned, programmatic manner.

Mindray has been pursuing global M&A since 2000, gaining experience, expertise, and confidence with each successive deal. The company has been aided in this effort by an M&A team recruited from among the developed world’s most accomplished deal makers. The core members of the M&A team include a former executive director of Goldman Sachs (Asia) and a senior lawyer in the U.S. The M&A team taps the expertise of an advisory team consisting of seasoned deal counselors from KPMG, O’Melveny & Myers, and UBS, among others, who have helped Mindray develop a systematic due-diligence and negotiation-management process, as well as a flexible and efficient decision-making system. Mindray has also carefully defined the roles of its management team, the core M&A team, and professional advisors at each stage of the transaction, including preparing for and executing due diligence, approving decisions, and managing closing and PMI. That transactional excellence enabled Mindray not just to acquire Datascope’s patient-monitoring business but also to launch PMI activities before closing. The acquisition vaulted the combined company onto the global stage, and seven years after the deal’s closing, Mindray had become one of the top three companies in patient-monitoring systems worldwide and a leader in the intensely competitive North American health-care market.

Companies such as Lenovo and Mindray are in some ways emulating outbound acquirers from other parts of the developing world. Confounding observers who doubted that an organization from a developing country could manage a business based in a developed country, these companies have demonstrated world-class competence in M&A and PMI: they fielded armies of specialists to carry out deep-dive due diligence of target companies and followed up by flawlessly executing long-term PMI strategies that determined synergy targets and timelines—and hit them. They sent large management teams to oversee the integration process and set up systems to continuously improve the target’s operating efficiency and reap cost savings. These developing-world acquirers rigorously define standard operating procedures and establish best-practice databases to translate success stories and lessons learned into proprietary knowledge. This knowledge is stored in a repository accessible across the enterprise.

Playing to Win: Three Recommendations for Chinese Buyers in Outbound M&A

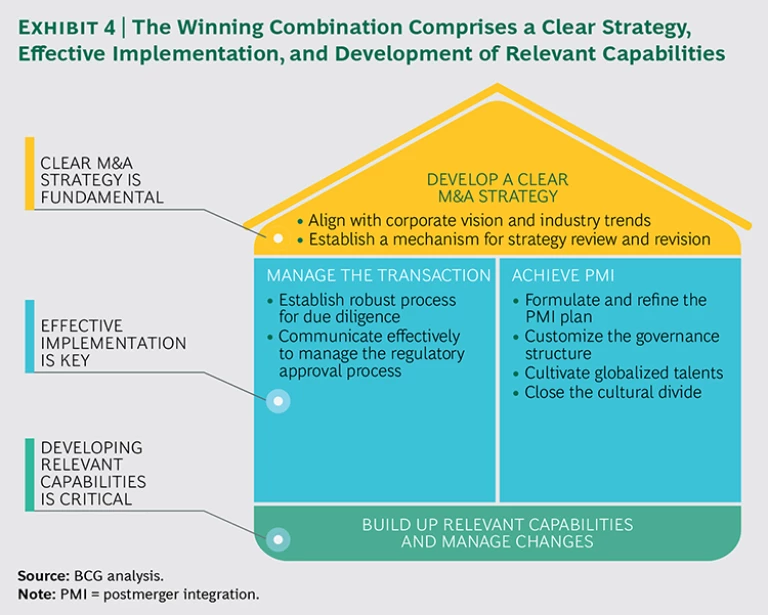

How can Chinese companies overcome the obstacles they so often encounter when pursuing outbound M&A? We believe that successful outbound deal making rests on three pillars: a clear M&A strategy, effective implementation, and building relevant capabilities. (See Exhibit 4.) Thus, we offer the following recommendations to senior executives of Chinese companies aiming to step up onto the global stage.

Start with a clear strategy. We urge corporate leaders to take full advantage of both internal resources and external tools for handling data. Map out high-priority areas for outbound M&A on the basis of corporate vision, strategy, and a thorough analysis of industry developments, such as evolving trends in policy and technology and changes in consumption habits—the building blocks of a clearly defined outbound M&A strategy.

The strategy should spell out in detail the direction that overseas M&A should follow, and it should reflect the deal-making rationale: Is the company pursuing M&A activities to access new markets, acquire technology, or secure supplies of key resources? What industry segment does the company seek to enter? What areas should the company target as high priorities? What types of deal structure and financing sources are appropriate for the deals contemplated?

Companies should also establish a specialized system for developing and revising outbound M&A strategy. The system should clearly define the following:

- The participants in M&A strategy development

- Processes, such as those for regular communication to ensure that key stakeholders are kept up to date on the company’s evolving M&A strategy

- An evaluation and review system

- Methods and instruction manuals for conducting industry analysis

- Project screening and target analysis

Focus on effective implementation. Effective implementation depends on well-managed and robust due diligence, negotiation, and approval processes. Companies must be able to identify transaction risks, make decisions, plan and execute PMI, realize synergies, and achieve business growth.

Doing so requires senior management to establish an effective scheme to manage the due diligence and review processes, including in the commercial, legal, financial, and technological areas. Commercial due diligence should focus on the attractiveness of the target and potential market, possible synergies, the business plan and company valuation, and the feasibility of execution. During management reviews, it is critical to identify key stakeholders, draw up a detailed communication plan, and meticulously prepare communication materials.

Up-front and comprehensive preparation and integration are critical to effective implementation. Acquirers must rigorously assess potential synergies, making sure that integration philosophies are aligned. It’s equally important to formulate and agree on a plan for the first 100 days following the closing of the deal. During that crucial period, acquirers should set up an appropriate overseas governance structure with financial, strategic, and operational governance centers and decision-making processes.

People issues are important as well. Acquirers should develop a cross-cultural management talent pool through both internal development and external recruitment. This effort demands that management establish a flexible communication system and define a communication plan for the management team and employees alike. Iterative and in-depth interaction will mitigate conflicts caused by differences in culture and management style. But acquirers must not become complacent; cultural differences require constant attention. They should establish a scheme to manage uncertainty and change within constantly changing external and internal environments.

Develop relevant capabilities and hone them with each new deal. In the long run, if M&A is to be an engine for corporate development, companies will need to nurture and perfect a set of core strategic, organizational, process, and governance capabilities to support outbound M&A.

Outbound M&A requires competency in strategic planning. The corporate development plan and vision should guide the design of an explicit outbound M&A strategy that identifies high-priority regions, industry segments, and approach to deals, and defines the target-selection process and the frequency and timing of M&A. Acquirers will also benefit from establishing an M&A knowledge database that incorporates relevant information about target companies; processes, tools, and templates for M&A deals; input about M&A decision making; and key lessons learned from M&A activities. This knowledge should inform the company’s revisions to its M&A strategy and support the continuous improvement of the M&A function.

Acquirers should focus as well on developing and retaining top talent with expertise in international business management. Through both external recruiting and internal training, companies can create a pool of top management talent with cross-border and cross-cultural backgrounds, well-balanced areas of expertise, and diversified project experience. When General Motors acquired Daewoo in 2002, it set up a PMI team of about 500 specialists. The team members were all top players in the field of cross-border and cross-cultural management. They were led by a high-profile group of 50 executives tasked to ensure seamless integration of the two organizations. GM used incentives—including equity, compensation and benefits, promotions, employee care, and an enhanced sense of belonging—to attract and retain core talent from the target company. As a result, the target’s valuable intangible assets were preserved, the complexity of the integration was kept to a minimum, core resources were retained, and both organizations were able to successfully navigate the PMI period relatively painlessly.

Specialized management of the M&A process is essential. That means setting up a dedicated M&A function, devoting appropriate resources to it, and engaging relevant external experts to direct M&A activities and coordinate internal and external resources. Establishing a robust system to maximize teamwork across business units and functions will clarify both M&A work flows and the roles and responsibilities of each function and employee. Robust program and process management tools —such as process manuals, checklists, and benchmarking—will support and improve M&A performance. An explicit process-monitoring and review system will enable management to continuously improve M&A activities.

Companies should also create an explicit KPI system for M&A programs, with clearly defined KPIs, detailed review processes, and regular check-ups for every business unit, function, and individual involved in M&A activities. Doing so will form the backbone of a consistent and visible reward and sanction mechanism linked to the company’s annual performance-review system. Effective management will also require a detailed governance system that enables management to monitor and review all M&A activities. The corporate M&A decision-review system should be fully empowered to make the right decisions and effectively review M&A performance.

Corporate China’s globalization drive, with all its attendant M&A activity, is still in its infancy, relatively speaking, and it’s no surprise that acquirers are experiencing growing pains as they make their move onto the world stage. But competition for the most desirable assets is fierce, and rivals from the developed world aren’t waiting around for China to catch up to them. It is therefore incumbent upon Chinese acquirers to study their failures as well as their successes and learn from the experience of other acquirers—especially those in the developing world—that are actively pursuing outbound deals. It will be neither easy nor inexpensive for Chinese companies to professionalize their M&A functions and attract top talent with international experience and expertise in overseas deal making. But the prize is well worth the effort. In today’s M&A environment, Chinese companies have a golden opportunity to claim their place among the world’s leading corporations.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Curtis Che, Eugene Khoo, Eric Zeng, and Yulin Zhu for their contributions to the development of this report.