Minority investments have long been a common feature of smaller growth-equity deals. Recently, however, minority deals have become increasingly prevalent in larger private-equity (PE) transactions. In fact, minority investments now occupy a prominent place in the investment strategies of many buyout-oriented mid- and large-cap funds.

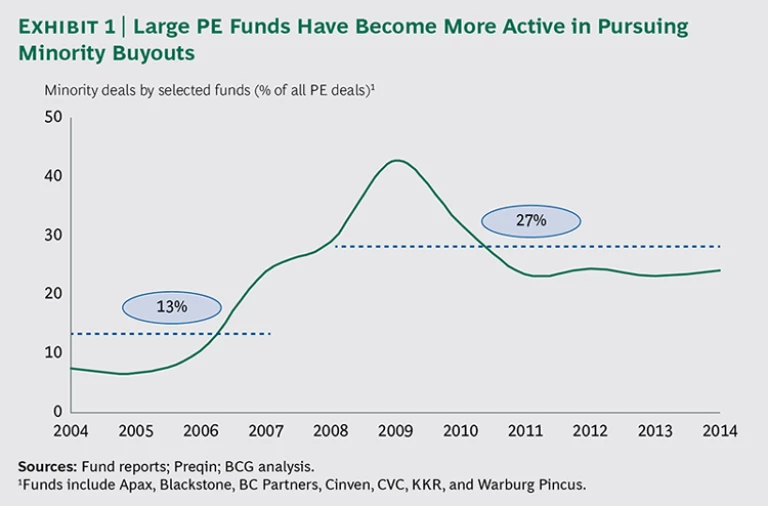

The Boston Consulting Group analyzed a sampling of deals entered into by seven representative large PE funds and found marked growth in the proportion of minority stakes in the past few years, from an average of 13 percent of deals done globally from 2004 through 2007 to 27 percent of deals since 2008. (See Exhibit 1.)

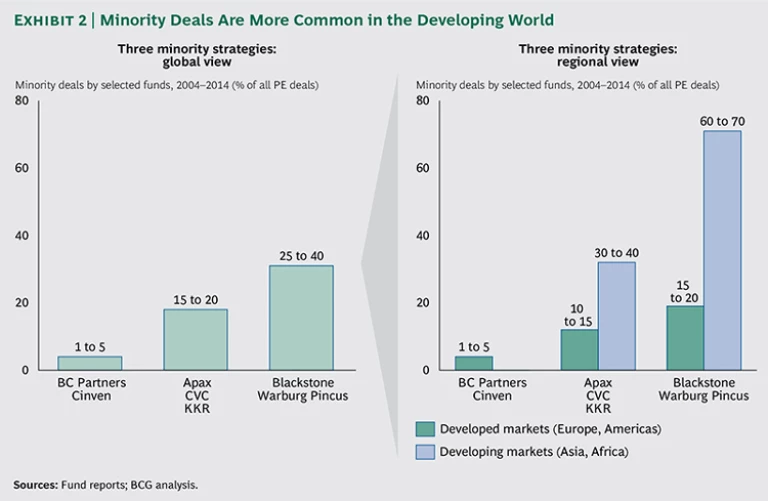

Many of the largest global PE firms have embraced minority-investing opportunities, even as some of the more Europe-focused large players appear to have shunned them. From 2004 through 2014, for example, 15 to 20 percent of deals done by

Apax, CVC, and KKR were minority deals, and 25 to 40 percent of Blackstone and Warburg Pincus deals involved minority stakes. By contrast, minority interests characterized less than 5 percent of deals entered into by Cinven and BC Partners. (See Exhibit 2.) This divergence is in part a function of whether a firm is active in the developing world, where minority deals are more common, but such deals have also come to play an increasingly important part in some players’ developed-market strategies.

Why Sellers Choose to Sell Minority Stakes

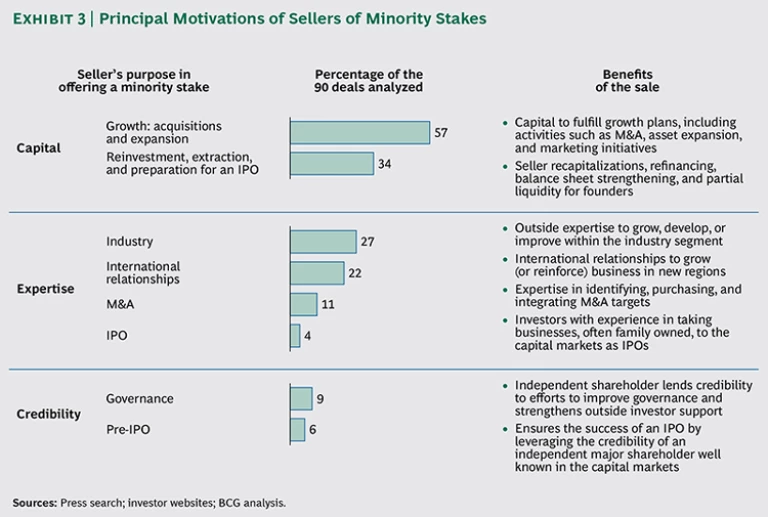

According to BCG’s analysis of 90 minority positions taken from 2004 through 2014, the three main motivations of sellers of minority stakes are the need to raise capital, the desire for specific expertise, and the desire for the credibility that an independent, professional investor can bring. (See Exhibit 3.)

More than 90 percent of the minority deals analyzed by BCG explicitly mentioned the need to access capital. Approximately 57 percent mentioned the need to raise capital to fund growth or acquisitions. For example, Czech security-software company Avast Software disclosed that it had sold a minority stake to CVC in early 2014 to access the capital it needed to continue adding to its product base and to expand further into the U.S. At the time of the deal announcement, Avast CEO Vincent Steckler told PEhub.com, a website that covers the PE industry, “We are not yet number one in every market. CVC gives us the resources to grow to become the number-one PC security provider in the U.S. and Asia, and the clear market leader in mobile security.”

For 34 percent of sellers, minority sales were an attractive means of extracting capital for the current owners while allowing them to maintain control. For example, when Apax acquired a minority position in Eastern European media company CME, its founder, Ronald Lauder, described the deal as a way “to diversify my personal investments and recognize a return on a part of my initial investment in the company, while remaining CME’s largest shareholder.”

Minority investing gained favor during the peak of the financial crisis, when debt finance was severely constrained and the sale of a minority stake was often the only way for a company to raise much-needed capital. It came at a high cost. Minority sellers paid the higher returns demanded by equity investors and accepted dilution of the original owner’s stake. Today, the debt-financing squeeze has largely passed, but some corporate balance sheets remain constrained, providing a motivation to sell minority stakes.

Several European banks, for example, have recently sold or announced their intention to sell minority stakes in some of their operating units. In 2014, Santander sold 50 percent of its custody business to Warburg Pincus and Temasek, netting

a $550 million gain that the Spanish bank used to strengthen its capital base. The sale added 12 basis points to Santander’s common-equity Tier 1 ratio, significantly strengthening what analysts regarded as one of the tightest core-capital ratios among European peers. A year before, Santander had sold 50 percent of its asset-management business to Warburg Pincus and General Atlantic in a deal estimated to have generated net capital gains of $850 million for the Spanish bank.

Sellers of minority stakes seek more than capital alone. As many as a quarter of the deals that we analyzed explicitly mentioned that an important benefit of the transaction was access to the expertise that PE funds can provide. In particular, companies that sell minority stakes seek deep knowledge about adjacent industry subsectors and expertise about how to spur growth in new regions. Sellers also place a high value on expertise in mergers and acquisitions and initial public offerings.

The successful journey of KKR and Wild Flavors from 2010 to 2014 is an illustrative example. At the time of KKR’s acquisition of a 35 percent stake in the German flavor manufacturer, the latter’s founder, Hans-Peter Wild, commented that “this strategic partnership will allow us to tap into the capital markets and financing sources that have previously been unavailable to us….KKR is a strong partner with extensive global expertise and will assist Wild in its focused expansion and strengthening of our businesses going forward.” Following the sale, Wild embarked on a global M&A program, acquiring Cargill’s juice-blends business, mint-oil maker A.M. Todd, and natural-extracts maker Alfrebro. The deals expanded Wild’s presence in Europe, India, Japan, and the U.S. In 2014, its sales having quadrupled to around €2 billion since 2010, Wild accepted a 100 percent buyout offer from strategic acquirer ADM. Priced at €2.3 billion, a handsome 16 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, the sale trebled the value of KKR’s initial investment in the company.

Finally, a number of deal announcements explicitly cited the credibility that an independent shareholder can provide. U.S. cloud-storage provider Box, for instance, raised $150 million from TPG and Coatue Management in 2014. According to Bloomberg.com, Box did the deal to buy time for its planned IPO and to reassure investors that doubted Box’s staying power, given its rapid cash burn.

HOW MINORITY DEALS VARY BY REGION

Minority deals, still something of a rarity in the U.S., are more common in Europe and especially Asia. In those two latter regions, local market conditions and sellers’ motivations, described below, lead to a higher incidence of minority plays.

Asia

Historically, minority deals have been more common in emerging markets—especially Asia—than in Europe and North America. Several factors account for the difference.

In the first place, the share of businesses that are family owned or controlled in many developing markets is very high. As much as 85 percent of businesses with $1 billion or more in annual revenues in Southeast Asia are family run, compared with 15 percent of U.S. companies in the Fortune Global 500. Owners in developing countries are often less willing to cash out their stakes completely, because less sophisticated stock markets make it more difficult to diversify wealth and assets efficiently. In addition, political considerations often influence a government’s decision to sell only minority stakes in state-owned enterprises.

In some countries, significant regulatory barriers prevent foreign investors from owning majority or controlling stakes in local enterprises. In a number of Chinese industry sectors, foreign companies are either required to form joint ventures with domestic businesses or are limited to minority stakes by law.

Personal relationships can also play an even bigger role than in developed markets, making it more attractive for PE investors to support local players with existing relationships.

Europe

As in Asia, local dynamics in Europe lead to a greater prevalence of minority deals compared with North America. The four funds with a significant number of investments in both Europe and the Americas that we analyzed did minority deals in 17 percent of cases in Europe, as against only 12 percent in the Americas.

What accounts for the difference? In Europe, families control 40 percent of big listed companies. These families are often keen to preserve control for financial and social reasons and therefore tend to favor minority deals. In addition, Europe’s debt-capital markets are somewhat less developed and its banking sector under more pressure than in the U.S., making access to debt financing on the open market problematic and encouraging companies to favor equity offerings over debt issuance. Moreover, Europe’s fragmentation results in a lower level of standardization, liquidity, and scale for credit risk analysis, making private placements more expensive and hindering the development of the secondary market, even though the EU and U.S. economies are roughly comparable in size. In 2014, the European private-placement debt market totaled $99 billion, compared with $234 billion in the U.S.

European deals tend to be smaller than those in the U.S., with North American deals averaging $500 million, compared with $300 million in Europe, and minority investments are more commonly featured in smaller deals.

Finally, compared with the investment theses underlying North American deals, those still figuring prominently in European deals—such as in-market and cross-border growth, professionalization, governance enhancement, and consolidation of fragmented sectors—are elements of value creation well suited to PE sponsor engagement as a minority investor. By contrast, hard cost-cutting, operational performance improvement, and restructuring are elements of value creation that typically are more successful with the active engagement of a control-oriented sponsor.

In similar fashion, when the founder of French fashion firm Zadig & Voltaire sold a 30 percent stake to TA Associates in 2012, the company stated that the sale would contribute to the professionalization of its governance, accelerate growth, and help transform it from a small family-owned business to a professionally managed enterprise. (See the sidebar, “How Minority Deals Vary by Region.”)

What PE Buyers See in Minority Deals

What reasons would justify minority investments by PE funds, given the obvious limitation of lack of control?

The first is that competition is often less intense for minority stakes than for majority deals. As we have mentioned, many sellers look for more than capital alone, and buyers can therefore differentiate themselves by factors other than price. In many cases, winning buyers can offer credibility in the financial markets and specific expertise relevant to the priorities of the company in question (in particular, regarding inorganic growth and internationalization). Because sellers do not choose buyers on the basis of price alone, PE firms are more likely to avoid the “winner’s curse” of overpaying.

What’s more, sellers often don’t want to publicize their desire to attract a third-party partner and sell a minority stake, fearing adverse publicity and customer fallout if the transaction fails. As a result, unlike the vast majority of control deals, minority deals are typically not consummated through formal auctions. We studied 24 recent minority deals done by large-cap PE firms in Europe and the U.S., and there was public evidence of an auction in only two instances—in contrast to most large PE deals, in which auctions are the norm.

As many as half of the deal announcements we analyzed cited the need for growth capital, which suggests that companies selling minority stakes often have attractive growth prospects, specific expansion plans, and clear roadmaps for investing the additional capital raised. What’s more, some PE professionals contend that minority stakes are less likely to be “lemons” with hidden flaws, noting that a majority shareholder’s desire to maintain control and a significant economic interest is a telling indicator of the shareholder’s confidence in the business’s prospects.

Morgan Stanley Alternative Investment Partners, an $11 billion fund investment and direct coinvestment business, has analyzed 215 deals (including both majority and minority transactions) that involved funds in which MSAIP had a position. The analysis indicated robust overall performance across both majority deals and those minority deals focused on more mature, nonventure businesses. The observed performance differential, however, evolved over time. Specifically, for deals entered into during the period from 2002 to 2007, majority deals evidenced a 30 to 50 percent approximate median differential in terms of money multiple returns. But there was no significant performance differential between majority and minority deals during the period from 2008 through 2013. Neil Harper, chief investment officer of the MSAIP Private Equity Funds-of-Fund team, observed that “from our experience, funds that demonstrate the ability to flex between controlling and significant minority stakes perform at least as well as funds focused only on control, and even outperform such funds in some cases and some markets.”

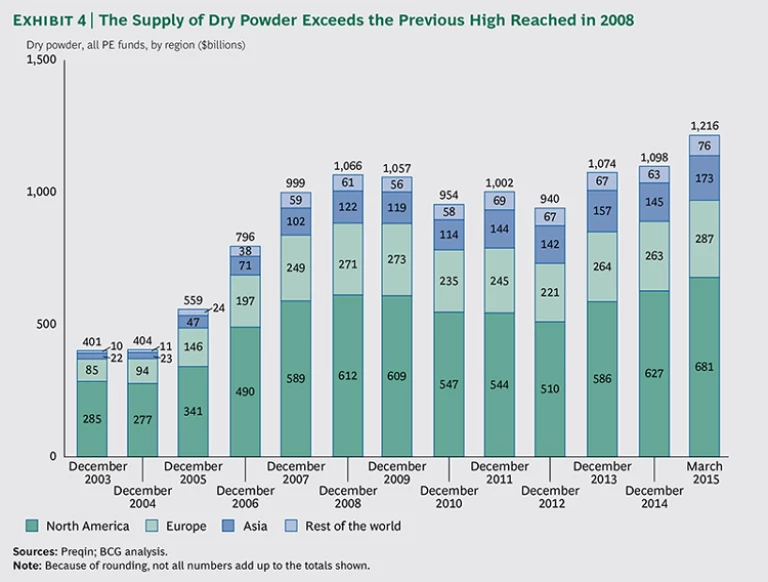

Perhaps in consequence, demand for minority deals has risen sharply in recent years. Buyout funds are sitting on approximately $1.2 trillion of uninvested capital, slightly more “dry powder” than the previous peak reached at the end of 2008, and they are on the hunt for opportunities to put this capital to work, sometimes in unconventional ways. (See Exhibit 4.)

How to Make Minority Deals Work

Although minority deals can be attractive for PE investors and sellers alike, the lack of control requires PE firms to adjust their standard approach to accommodate several additional success factors. They need to do the following:

- Adopt a proactive origination strategy and invest time to build relationships. In an environment of record dry powder and rising multiples, many PE funds will aim to increase their sourcing of minority deals. First, they should make sure they have in place the prerequisites for any investment, minority or majority: a systematic screening process, appropriate customer-relationship-management tools, and committed deal-sourcing professionals and advisor networks. Second, and probably even more important here than in majority deals, PE funds should adopt a highly proactive origination strategy that will allow them to create opportunities rather than wait for them. Investing in building relationships with family owners and senior managers will take time and effort, but all the calls, meetings, and industry conferences will eventually pay off.

- Ensure that the investment thesis fits the ownership structure. Minority ownership interests can work well when the key means of value creation are related to top-line growth and governance. These include facilitating organic or inorganic cross-border growth, professionalizing management teams and processes, enhancing governance, and consolidating fragmented sectors. Minority investing can become problematic, however, when the investment thesis hinges on activities such as creating value through restructuring, improving operational performance, cost cutting, and supply chain initiatives. In these instances, majority ownership and a hands-on, control-oriented approach are often more appropriate.

- Make sure not to settle for a minority stake as a consolation prize. The PE firm should take care when settling for a minority stake if a majority stake was the initial goal. As one PE practitioner put it, “There is a risk that you fall in love with the deal and don’t want to let go after all the effort, despite the fact that the investment is not really suited for a minority position.”

- Put a veto in place. Even without control, the minority investor can and should secure significant influence over critical decisions such as acquisitions and asset disposals, issuance of new equity or debt, changes in board composition, and replacement of key members of the management team.

- Understand your partner and think two moves ahead. To a great extent, minority deals succeed because the PE fund understands the majority owners or founders, their motivations and intentions, and the surrounding context. Being able to anticipate areas of alignment and misalignment, foresee the owners’ reactions, and evaluate a range of contingencies are key to enabling the PE fund to build a successful relationship with its partner.

- Invest in your relationship with the CEO and senior management team. As discussed in a previous report, successful relationships between PE funds and the management teams of portfolio companies demand continuous effort from both sides. (See Private Equity and the CEO: Partners in the Quest for Value, BCG Focus, November 2013.) This effort is particularly important with minority investments, which by definition preclude a directive approach. PE minority investors succeed by building a trusting partnership with the management team. This entails understanding its priorities, defining clear objectives together, bringing in trusted experts who can support strategic and operational projects, and maintaining transparency throughout the relationship.

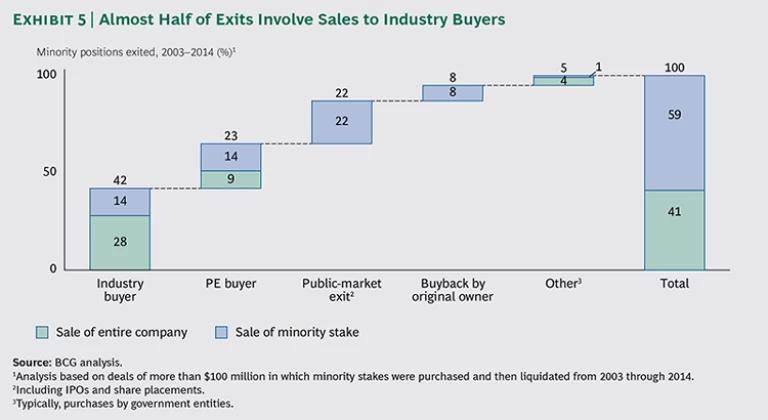

- Prepare extensively for getting out before going in. In a BCG analysis of sizable minority exits, almost half of minority investments were subsequently sold to industry buyers, with a further quarter passing to other PE funds in secondary transactions. (See Exhibit 5.) In only 10 percent of cases were companies floated in an IPO, and in only 8 percent were they sold back to their founders. In many cases, majority and minority shareholders exited at the same time, either voluntarily or because the terms of the deal demanded it. In the majority of cases, however, the minority investor was the only seller. In such cases, minority and majority shareholders often have different priorities and respond to different incentives. Minority investments therefore require up-front planning on multiple exit aspects, even more so than in control deals. Having significant influence (if not control) over the exit—for example, with put or drag-along rights—should be a key consideration from the beginning of deal negotiations. In many cases, the minority shareholder has the right, at a prearranged date or trigger event (such as failure to meet specified financial indicators or the loss of critical talent), either to force the majority shareholder to buy back the minority stake using predetermined valuation metrics or to force a joint sale or IPO of the whole company.

By adhering to these precepts, PE professionals can realize competitive returns, diversify their portfolios, deploy built-up capital, and produce big results from relatively small investments. The payoffs could convince even the most skeptical observers that less can, indeed, be more.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Neil W. Harper, managing director and chief investment officer of Morgan Stanley Alternative Investment Partners, for his valuable contributions to this report and his helpful thought partnership.